Will data centers crash the economy?

This time let's think about a financial crisis before it happens.

The U.S. economic data for the last few months is looking decidedly meh. The latest employment numbers were so bad that Trump actually fired the head of the Bureau of Labor Statistics, accusing her of manipulating the numbers to make him look bad. But there’s one huge bright spot amid the gloom: an incredible AI data center building boom.

AI technology is advancing fast, threatening (promising?) to upend many sectors of the economy. Nobody knows yet exactly who will profit from this boom, but one thing that’s certain is that it’s going to take a lot of computing power (or “compute”, as they say). AI models take a lot of compute to train, but nowadays they also take a lot of compute to do inference — i.e., to “think about” and answer each question you ask. Inference compute now represents most of the cost of running advanced AI models, and increases in inference compute are responsible for many of the ongoing performance gains. So compute needs are probably only going to grow as AI keeps getting better.

Whoever provides this compute is going to make a huge amount of revenue. Whether that means they’ll make a lot of profit is another question, but let’s table that for right now; you can’t make profit if you don’t make revenue. So right now, tech companies have the choice to either sit out of the boom entirely, or spend big and hope they can figure out how to make a profit.

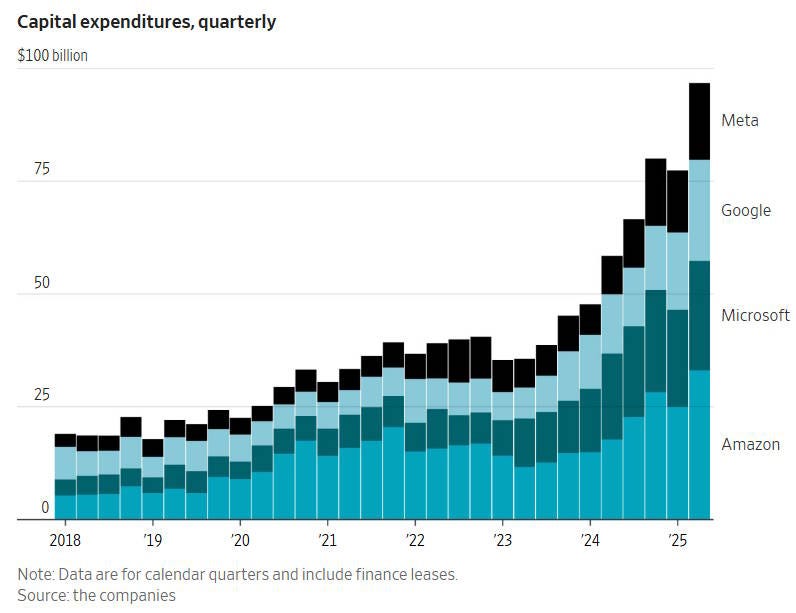

Roughly speaking, Apple is choosing the former, while the big software companies — Google, Meta, Microsoft, and Amazon — are choosing the latter. These spending numbers are pretty incredible:

For Microsoft and Meta, this capital expenditure is now more than a third of their total sales.

Here’s Chris Mims of the WSJ:

The Magnificent 7 tech firms have collectively spent a record $102.5 billion on capex in their most recent quarters, nearly all from Meta, Alphabet (Google), Microsoft and Amazon. (Apple, Nvidia and Tesla together contributed a mere $6.7 billion.)…

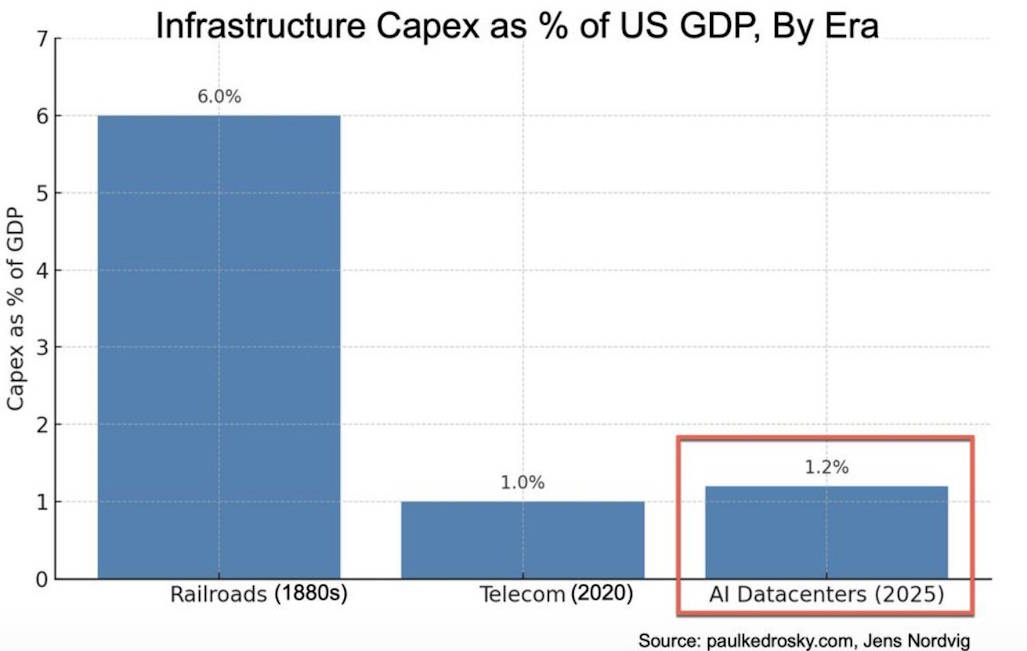

Investor and tech pundit Paul Kedrosky says that, as a percentage of gross domestic product, spending on AI infrastructure has already exceeded spending on telecom and internet infrastructure from the dot-com boom—and it’s still growing. He also argues that one explanation for the U.S. economy’s ongoing strength, despite tariffs, is that spending on IT infrastructure is so big that it’s acting as a sort of private-sector stimulus program…

Capex spending for AI contributed more to growth in the U.S. economy in the past two quarters than all of consumer spending, says Neil Dutta, head of economic research at Renaissance Macro Research, citing data from the Bureau of Economic Analysis. [emphasis mine]

Here’s that chart from Kedrosky, who has been doing an excellent job following this story as it unfolds:

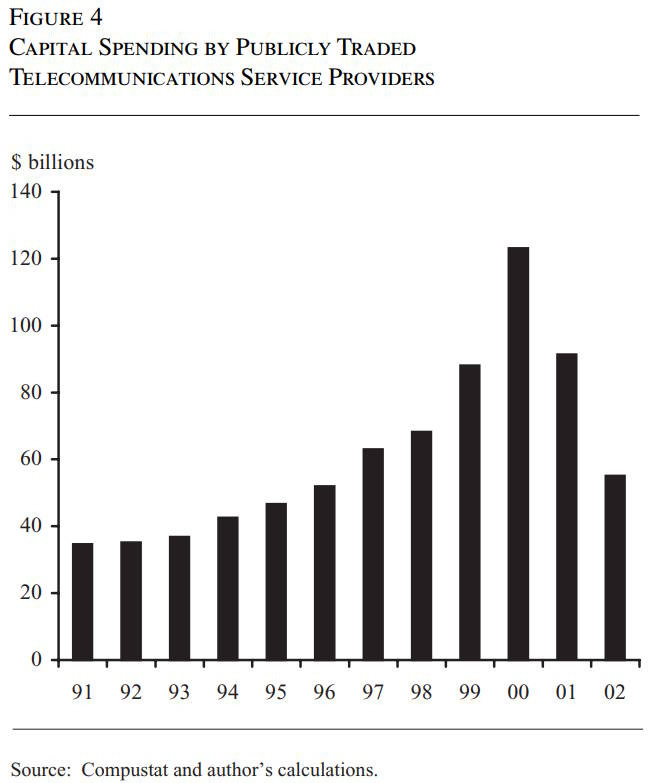

Side note: I’m actually not sure Kedrosky is right about the height of the telecom boom. His chart shows the level of capex for 2020, when 5G and fiber infrastructure was being built out. But Doms (2004) shows U.S. telecom capex reaching $120 billion in 2000:

That would have been around 1.2% of U.S. GDP at the time — about where the data center boom is now. But the data center boom is still ramping up, and there’s no obvious reason to think 2025 is the peak, so Kedrosky’s point still stands.

I think it’s important to look at the telecom boom of the 1990s rather than the one in the 2010s, because the former led to a gigantic crash. The railroad boom led to a gigantic crash too, in 1873 (before the investment peak on Kedrosky’s chart). In both cases, companies built too much infrastructure, outrunning growth in demand for that infrastructure, and suffered a devastating bust as expectations reset and loans couldn’t be paid back.

In both cases, though, the big capex spenders weren’t wrong, they were just early. Eventually, we ended up using all of those railroads and all of those telecom fibers, and much more. This has led a lot of people to speculate that big investment bubbles might actually be beneficial to the economy, since manias leave behind a surplus of cheap infrastructure that can be used to power future technological advances and new business models.

But for anyone who gets caught up in the crash, the future benefits to society are of cold comfort. So a lot of people are worrying that there’s going to be a crash in the AI data center industry, and thus in Big Tech in general, if AI industry revenue doesn’t grow fast enough to keep up with the capex boom over the next few years.1

A data center bust would mean that Big Tech shareholders would lose a lot of money, like dot-com shareholders in 2000. It would also slow the economy directly, because Big Tech companies would stop investing. But the scariest possibility is that it would cause a financial crisis.

Financial crises tend to involve bank debt. When a financial bubble and crash is mostly a fall in the value of stocks and bonds, everyone takes losses and then just sort of walks away, a bit poorer — like in 2000. Jorda, Schularick, and Taylor (2015) survey the history of bubbles and crashes, and they find that debt (also called “credit” and “leverage”) is a key predictor of whether a bubble ends up hurting the real economy. They write:

Using a comprehensive dataset, covering a wide range of macroeconomic and financial variables, we demonstrate that it is the interaction of asset price bubbles and credit growth that poses the gravest risk to financial stability. These results, based on long-rung historical data, offer the first sound statistical support based on large samples for the widely held view that the financial stability risks stemming from of an unleveraged equity market boom gone bust (such as the U.S. dotcom bubble) can differ substantially from a credit-financed housing boom gone bust (such as the U.S. 2000s housing market).

They use the terms “unleveraged” and “credit”, but what they really mean here — and the way they define their variable for credit growth — is specifically bank loans, not bonds. In the 2008 crash, most of the debt was held by banks, in one form or another. Thus, a wave of defaults threatened the solvency of the banking system, causing the entire economy to freeze up.

But the banking system wasn’t in any real danger of collapse from the dot-com/telecom crash, because banks hadn’t lent a lot of money to people involved with the tech industry, so there weren’t a lot of loans to go bad. The telecom companies had borrowed a lot, but primarily via the bond markets rather than from banks, which at the time were more focused on housing and small business. Households also didn’t become significantly more indebted in the 90s (relative to their income), which is probably why there wasn’t a long and painful period of household deleveraging following the dotcom boom, the way there was after 2008.

So if we believe this basic story of when to be afraid of capex busts, it means that we have to care about who is lending money to these Big Tech companies to build all these data centers. That way, we can figure out whether we’re worried about what happens to those lenders if Big Tech can’t pay the money back.

Paul Kedrosky has a list:

Where is all this capital coming from?

For the most part, six sources:

Internal Cash Flows (Primary for Microsoft, Google, Amazon, Meta, etc. )

Debt Issuance (Rising role)

Equity & Follow-on Offerings

Venture Capital / Private Equity (CoreWeave, Lambda, etc.)

SPVs, Leasing, and Asset-Backed Vehicles (like Meta's recent)

Cloud Consumption Commitments (mostly hyperscalers)

And The Economist writes:

[C]apex is growing faster than [Big Tech’s] cashflows…The hot centre of the AI boom is moving from stockmarkets to debt markets…During the first half of the year investment-grade borrowing by tech firms was 70% higher than in the first six months of 2024. In April Alphabet issued bonds for the first time since 2020. Microsoft has reduced its cash pile but its finance leases—a type of debt mostly related to data centres—nearly tripled since 2023, to $46bn (a further $93bn of such liabilities are not yet on its balance-sheet). Meta is in talks to borrow around $30bn from private-credit lenders including Apollo, Brookfield and Carlyle. The market for debt securities backed by borrowing related to data centres, where liabilities are pooled and sliced up in a way similar to mortgage bonds, has grown from almost nothing in 2018 to around $50bn today…

CoreWeave, an ai cloud firm, has borrowed liberally from private-credit funds and bond investors to buy chips from Nvidia. Fluidstack, another cloud-computing startup, is also borrowing heavily, using its chips as collateral. SoftBank, a Japanese firm, is financing its share of a giant partnership with Openai, the maker of ChatGPT, with debt. “They don’t actually have the money,” wrote Elon Musk when the partnership was announced in January. After raising $5bn of debt earlier this year xAI, Mr Musk’s own startup, is reportedly borrowing $12bn to buy chips.

Some of these funding sources don’t seem that dangerous, in the macroeconomic sense. When Big Tech or other companies spend their own cash, issues stock, or issue bonds, it looks more like the telecom boom of the 1990s than the railroad boom of the 1800s.

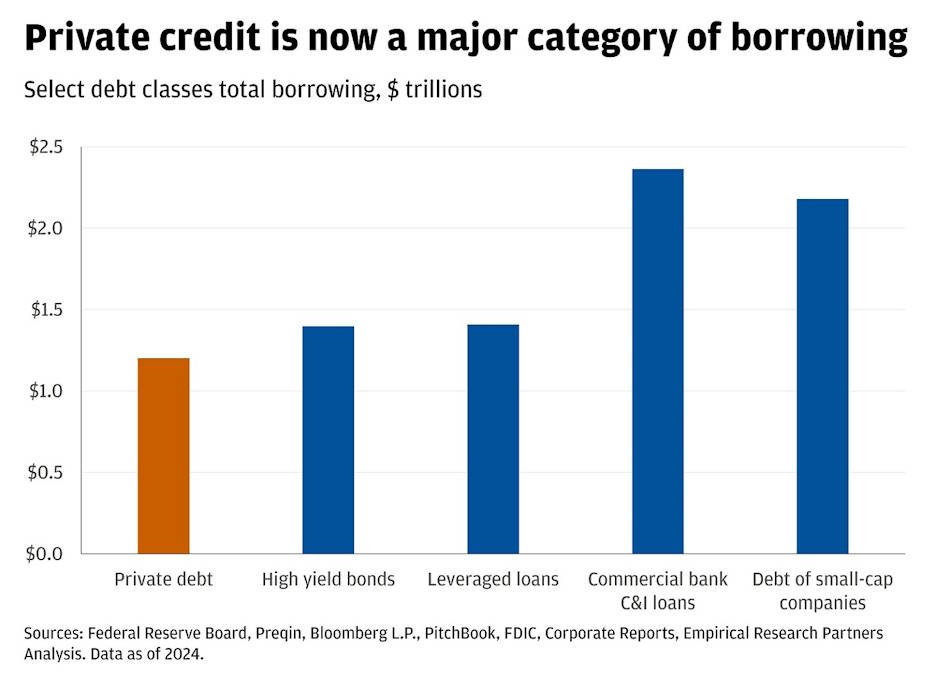

But what about all this “private credit”? These are the potentially scary part. Private credit funds are basically companies that take investment, borrow money, and then lend that money out in private (i.e. opaque) markets. They’re the debt version of private equity, and in recent years they’ve grown rapidly to become one of the U.S.’ economy’s major categories of debt:

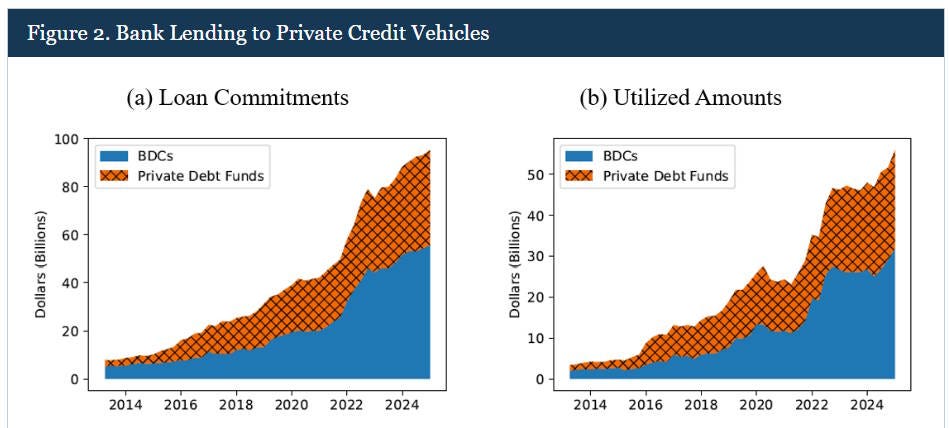

Private credit funds take some of their financing as equity, but they also borrow money. Some of this money is borrowed from banks. In 2013, only 1% of U.S. banks’ total loans to non-bank financial institutions was to private equity and private credit firms; today, it’s 14%. A recent note by Berrospide et al. of the Federal Reserve shows the rise in bank lending to private credit:

BDCs are “Business Development Companies”, which are a type of private credit fund. If there’s a bust in private credit, that’s an acronym you’ll be hearing a lot.

And I believe the graph above does not include bank purchases of bonds (CLOs) issued by private credit companies. If private credit goes bust, those bank assets will go bust too, making banks’ balance sheets weaker.

A recent article by Fillat et al. of the Boston Fed argues that bank lending to private credit funds might pose a systemic risk to the banking system:

The meteoric rise of private credit presents important questions about the role of banks going forward and the implications for stability in the US financial system…Our analysis of Federal Reserve and proprietary loan-level data indicates that the growth of private credit has been funded largely by bank loans and that banks have become a key source of liquidity, in the form of credit lines, for PC lenders. Banks’ extensive links to the PC market could be a concern because those links indirectly expose banks to the traditionally higher risks associated with PC loans.

The authors point out that most of these are very short-term loans — hence safer than long-term loans like the ones that sunk banks in the financial crisis of 2008. And most of them are senior loans — if private credit goes bust, banks get paid out first. But they caution:

[B]anks would suffer losses [on their private credit lending] only in severely adverse economic conditions, such as a deep and protracted recession. But losses could also occur in a less adverse scenario if the default correlation among the loans in PC portfolios turned out to be higher than anticipated—that is, if a larger-than-expected number of PC borrowers defaulted at the same time. Such tail risk may be underappreciated.

If all the private credit funds are lending to data centers, then their correlations are probably pretty high — if there’s a bust in AI, a lot of them will go bust at once. This could be the “tail risk” that the Boston Fed folks are worried about, and it seems like there’s a chance it could hurt the U.S. banking system.

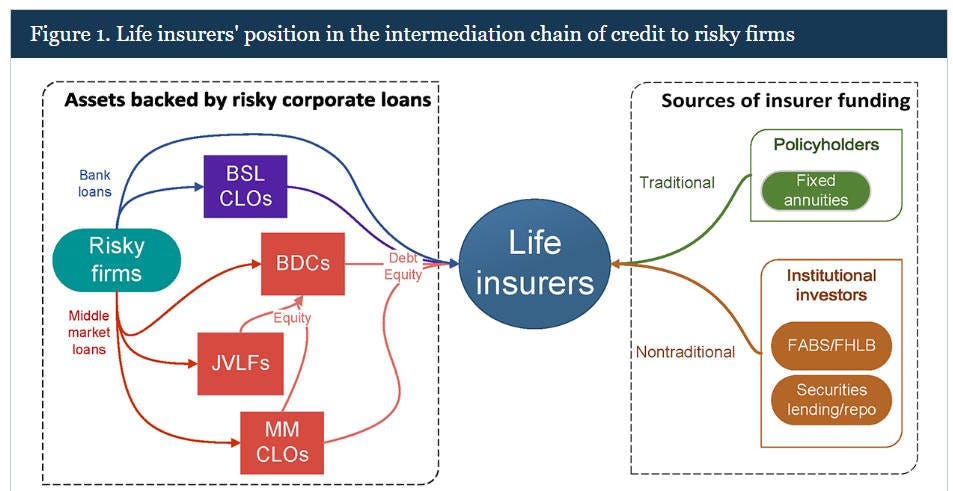

A private credit bust also could hurt insurance companies, who are the main LPs in the funds, but who also lend money to the funds. For example, Carlino et al. (2025) show how life insurers have basically become a kind of bank that borrows money from institutional investors and lends it to private credit:

They note, ominously, that “life insurers' exposure to below-investment-grade firm debt has boomed and now exceeds the industry's exposure to subprime residential mortgage-backed securities in late 2007.”

I’m not exactly sure how systemically important life insurance companies are; they’re intertwined with the rest of the financial system through a number of channels, and it’s hard to tell how significant those challenges are. But it seems like the possibility is there for some systemic effects. Meanwhile, other types of insurers are starting to lend to private credit as well. Remember that AIG, an insurance company, was one of the most important bailouts in the financial crisis of 2008.

So when I look at this entire landscape, it seems to me that some of the basic conditions of a financial crisis are at least starting to fall into place:

We have a big story about why “this time is different” — the idea that AI will change everything, and that data centers will thus earn huge returns.

We have a large and increasing amount of debt being used to fund one single sector of the economy (data centers), meaning that the loans’ default probability is probably highly correlated.

We have an opaque corner of the financial system (private credit) that has recently grown from a tiny piece of the system to a very significant piece.

We have systemically important lenders (banks, and possibly insurance companies) enmeshed in the new sector in a multitude of ways.

So far, the danger doesn’t scream “2008”. But if you wait until 2008 to start worrying, you’re going to get 2008. It’s good to start worrying early. Jamie Dimon, CEO of JP Morgan Chase, is not waiting to start sounding the alarm, warning that private credit could trigger the next financial crisis, even as his own company expands into the private credit market. As a former Citibank CEO said after 2008, “As long as the music is playing, you’ve got to get up and dance.”

Some people also worry that the U.S. power grid won’t be big and reliable enough to handle the new power demands from all these data centers. With Trump continuing his all-out attack on solar and wind energy, this is a real concern.

I was expecting your next post to be about the BLS and how we can be expecting record grain harvests this year…

Dumb questions alert...

Why do “Business Development Companies” exist ? Why don't businesses just get their loans from banks ? I'll guess it's because BDC's will make loans that Banks won't? But if that's it, why do banks make loans to companies that make loans that by the bank's standards are too risky ?