Why has American pop culture stagnated?

Predictably, my theories are all technological and economic.

In recent years, I’ve read a bunch of people talk about a stagnation in American pop culture. I doubt that this sort of complaint is particularly new. For decades in the mid-20th century, Dwight Macdonald railed against mass culture, which he viewed as polluting and absorbing high culture. In 1980, Pauline Kael wrote an op-ed in the New Yorker entitled “Why Are Movies So Bad? or, The Numbers”, where she argued that the capitalistic incentives of movie studios were causing them to turn out derivative slop.1

So if I try to answer the question “Why has American pop culture stagnated?”, there’s always the danger that I’ll be coming up with an explanation for a problem that doesn’t actually exist — that this is just one of those things that someone is always saying, much like “Kids these days don’t respect their parents anymore” and “Scientists have discovered everything there is to discover.” To make matters worse, there’s no objective definition of cultural stagnation in the first place; it’s a fun topic precisely because what feels new and interesting is purely a matter of opinion.

With that said, I do think there’s some evidence that many forms of U.S. pop culture — music, movies, video games, books — are stagnating, at least as far as mass consumption is concerned. For example, back in 2022, Adam Mastroianni had a good post where he showed that an increasing percent of what Americans consume comes from franchises, sequels, remakes, and established creators. Here’s his chart for movies:

And Ted Gioia, who is probably the most well-known proponent of the “cultural stagnation” thesis, has some more evidence:

I’ve written repeatedly about music fans choosing old songs instead of new ones. But this trend has gotten more extreme since I first covered it. According to the latest figures, only 27% of tracks streamed are new or recent…The $15 billion market for comic books is driven by the same brand franchises that were dominant in the 1960s and 1970s…The top grossing shows on Broadway in 2023 are also retreads from the last century. The Phantom of the Opera and The Lion King boast the highest weekly gross revenues this year…83% of Hollywood revenues now come from franchise films featuring familiar characters from the past.

For what it’s worth, most Americans share this sense of declinism when it comes to movies, music, and TV, telling pollsters that these things peaked somewhere between the 1970s and the 2000s. Maybe this is because most of the poll respondents are middle-aged people nostalgic for their youth. But as Gioia points out, young people are listening to music from their parents’ generation nowadays; that’s not simple nostalgia.

Personally speaking, I’ve felt this stagnation in a number of areas. Movies, for example, don’t feel nearly as interesting or as vital of an art form as they did when I was younger, despite the fact that you can now shoot an indie film on your phone. A decent amount of good music is coming out, but a lot of the best stuff feels like refinement of what came before.

To name just one small example, young people have once again become fans of shoegaze, a micro-genre of dreamy, layered rock music that I enjoyed back when I was young in the 2000s. I love this revival. Here are two examples of recent shoegaze songs that I thought were absolutely excellent:

To be honest, I like these songs just as much as my old favorites by My Bloody Valentine, Tokyo Shoegazer, Oeil, etc. But they’re recognizably the same thing. I guess maybe it’s natural for a middle-aged guy like me to be a fan of things that sound like the music he loved in his youth, but what’s really striking is that the kids are into this too.

And nostalgia can’t explain why TV seems to me like it’s been in a golden age over the past decade. I loved Star Trek: Deep Space Nine and Seinfeld when I was a kid, but there was just nothing like Game of Thrones, or Andor, or One Piece. The Karate Kid movies were great2, but they don’t compare to the TV show Cobra Kai. Even in middle age, I’m perfectly capable of recognizing novelty and improvement in pop culture. It’s just that most types of pop culture don’t seem like they’re innovating and pushing the boundaries like TV is.

So anyway, let’s assume for the moment that the pop culture stagnation is real, at least across many domains. Why would that be happening?

Technology moves first

A lot of people who write about culture seem to see it as something autonomous — either a grassroots upwelling that just sort of comes about on its own, or something imposed top-down from the people in power. The implication of this tacit assumption is that if a bunch of bloggers and critics and tastemakers get together and yell enough, culture will simply change. Perhaps if we call modern American pop culture “stagnant” enough, artists will be shamed into making something new.

I just have trouble seeing the world like that. My instinct is always to trace changes in culture to changes in economics — and, ultimately, to changes in technology. Technology maps out the space of the possible — together with nature itself, technology sets the boundaries for what human beings can do. That possibility space is then filled by human initiative and institutions, until they bump up against the walls.

Despite his famous line that “The culture always changes first,” Ted Gioia basically believes that the root of cultural stagnation is technological. He thinks the advent of the smartphone and scrolling social media feeds has made it hard for young people to pay attention to anything except the next quick dopamine hit, thus destroying the audience for longer, more sophisticated works of art. He writes:

Twenty years ago, the culture was flat. Today it’s flattened…I still participate in many web platforms…But now they feel constraining…Instead of connecting with people all over the world, I now get “streaming content” 24/7…Facebook no longer wants me stay in touch with friends overseas, or former classmates, or distant relatives. Instead it serves up memes and stupid short videos…And they are the exact same memes and videos playing non-stop on TikTok—and Instagram, Twitter, Threads, Bluesky, YouTube shorts, etc…“Are we all beginning to have the same taste?” asks critic Rebecca Nicholson—complaining about her inescapable sense of repetition and sameness pervading music, TV shows, films, and everything else.

Like most people, he blames specific bad guys — the social media companies that serve people their soulless algorithmic feeds. But those folks are just trying to make money, and doing what the market incentives tell them to do; if they didn’t, someone else would, and the end result would be the same.

Once it becomes possible for everyone to have an internet-connected supercomputer in their pocket, everyone will. Once it becomes possible to smoothly and seamlessly deliver infinite feeds of short-form video content to everyone’s phone, someone will do that too. And if people keep tapping and swiping on it, that’s what they’ll get served.3 In the absence of laws or other forms of government power to stop the market from working, the market will give people what they demand.

Only within the constrained space of that market demand do artists and creators have choices about what to make — at least, not if they want to make a living doing their art, or get their art in front of a large number of eyeballs. Sure, plenty of people make art as a hobby, out of pure passion. There are plenty of people out there still composing symphonies even as their peers hum the latest TikTok jingle. But the twin desires for money and popularity are strong for most artists, and that means that their output will be constrained by the market — which in turn will be determined by the intersection of preferences and technology.

But technology doesn’t only determine what consumers demand; it also determines what kinds of creations artists are able to supply.

The low-hanging fruit

When I was a kid, there was a popular genre of music called “alternative rock”. The melody of this type of music would often consist of a sequence of distorted power chords. Examples include “Shine” by Collective Soul, “Freak” by Silverchair, “Machinehead” by Bush, “All Over You” by Live, and so on.

It’s a nice sound, but it’s pretty limited in terms of what you can do with it — there are only so many short sequences of power chords you can construct. And during the mid to late 1990s, when every suburban boy in the country thought he was going to make it big as an alternative rock star, there were probably hundreds of thousands or even millions of guitar-playing youths sitting in their garages or their bedrooms finding every possible sequence. It was a swarm intelligence doing a brute-force grid-search algorithm over a fairly low-dimensional space.

I don’t think the 1990s kids found every possible alt-rock song. There were still some great new ones left to be written. Here’s “Chokecherry” by PONY, released in 2021:

But by and large, the alt-rockers successfully mined out all the low-hanging fruit of their micro-genre. There just wasn’t much left to do in that vein, and so the canon of alt-rock is now just mostly complete.

The alt-rock example illustrates how a particular entertainment format has a finite amount of low-hanging fruit that eventually runs out. In principle, the same should be true of much broader categories of entertainment — like melodic music itself.

The number of melodies that it’s possible to write is very large, but finite. In 2020, two programmers algorithmically generated every possible MIDI tune and published them for free, hoping to head off IP lawsuits about melodic plagiarism. Of course, that set of melodies is so large that in practice, it’ll be impossible for humans to record and release songs based on all of them.

But in practice, the number of melodies that tugs at human heartstrings is probably far fewer. These days when I search for new rock songs on Spotify and YouTube, most of what I find sounds like tuneless slop; the sequences of notes are technically a melody by some simple mathematical definition, but they don’t sound like anything to me.

And the more of the good melodies we find, the more similar the new melodies will sound to something that already exists. The Flaming Lips’ “Turn It On” has a different melody from Hootie and the Blowfish’s “Let Her Cry”, but it’s similar enough that if you try to hum one, you might accidentally find yourself humming the other. Kurt Cobain thought “Smells Like Teen Spirit” sounded like the Pixies song “Gouge Away”. Long before we exhaust all the melodic possibilities, we find enough of them where the distance from any new melody to the nearest old melody starts to shrink, making novelty feel more and more incremental.

The more constraining an entertainment format is — i.e., the smaller the space that artists have to search for novelty — the quicker the innovations stop feeling novel. For alternative rock, the space was very small. For melodic music, it’s bigger. For music as a whole, it’s far bigger — there are many musical elements that you can add to melodies in order to make the whole arrangement sound new, and some songs have no melody at all.

But even for music as a whole, there are probably a finite number of things you can do. There are probably a number of ways you can make music that conveys a sense of dreamy, ethereal longing, but not an infinite number of ways — and so when you try to evoke those emotions, you’re reasonably likely to end up with something that sounds a bit like shoegaze.

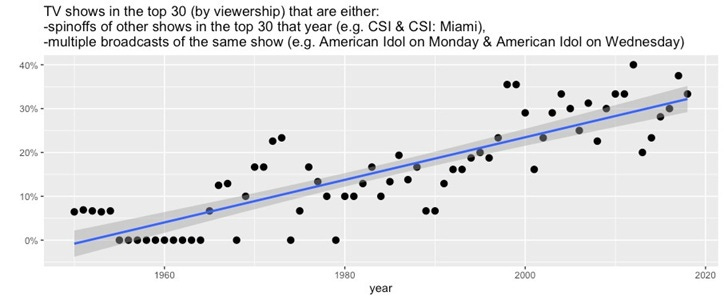

I wonder if this is why movies have become more repetitive than television. As Adam Mastroianni’s graph shows, movies took only about 20 years to go from 25% remakes and sequels to over 80%. But television’s novelty has decreased at a much slower rate:

Movies are simply much shorter than TV series. This constrains them pretty severely in terms of plot and characterization. When we talk about why Americans have been moving from the big screen to the small screen, we usually talk about the increasing quality of TVs. But it’s also possible that movies themselves may have exhausted a large fraction of their available novelty, while longer-format TV series are still going strong.4 This also might be why TV seemed like it was in a golden age in the 2010s, even as films’ creativity flagged.

The solution to this, of course, is to explore new artistic forms. If movies are getting stale, see what you can do with TV. If rock music is getting stale, see what you can do with electronica.

Some optimists argue that American pop culture isn’t stagnating at all — it’s just shifting to new and different forms. In a post last year, Katherine Dee argued that old formats like books, music, and movies have simply become less important, as cultural output has shifted to new formats:

[T]here’s a new culture all around us…We just don’t register it as “culture.”…We’re witnessing the rise of new forms of cultural expression. If these new forms aren’t dismissed by critics, it’s because most of them don’t even register as relevant…The social media personality is one example of a new form….not quite performance art, but something like it…The same is true of TikTok…[T]here is a lot of innovation on TikTok — particularly with comedy…Creating mood boards on Pinterest or curating aesthetics on TikTok are evolving art forms, too. Constructing an atmosphere, or “vibe,” through images and sounds, is itself a form of storytelling, one that’s been woefully misunderstood…They’re a type of immersive art that we don’t yet have the language to fully describe.

And Spencer Kornhaber writes something similar:

The great media of the 20th century—the art-pop album, the feature-length film, the gallery show, the literary novel—may be fighting for their life, but that’s because of competition from new forms defined by a sense of immediacy: short-form video, chatty podcasts, video games, memes. Like the old media, these forms foster tons of mediocrity. But they also invite surprising excellence[.]

If you look at the history of pop culture, novelty has always been driven by changes in technology. Rock music was able to exist only after the amplifier and the pickup microphone were invented. Electronic dance music was only able to exist after synthesizers, mixers, and samplers were created. Movies and TV required cameras and a host of other technologies. Even books were very hard to make before the printing press.

And yet in the realm of technology too, we may eventually see stagnation. Innovation is getting more expensive, and the pool of potential researchers is set to shrink. Perhaps AI can save us and revive both technological progress and cultural novelty, but that remains to be seen.

Where did the avant-garde go?

Existing alongside the criticism that American pop culture has become repetitive, there’s also the subtly different allegation that it has become less artistic — that the avant-garde has disappeared, replaced by shallow consumerist masscult. One of the chief proponents of this idea is my friend David Marx. In a response to Katherine Dee’s post about new cultural forms, he wrote:

TikTok/Reels skits just feel like the glossy, expertly-edited versions of the inside jokes that kids make at summer camp talent shows…Most of the creators…are non-art minded amateurs working in templated formats…“[D]igital vaudeville” says it all — it's just not an "inventive creative practice that expands what is possible with art."

And in a response to Spencer Kornhaber’s long piece in The Atlantic, Marx wrote:

The only way to define "progress" in culture is to draw clear lines between entertainment and art, something that has become extremely unpopular…A new critical consensus [in the 2000s and 2010s] demanded that we stop thinking about creativity in a hierarchical way: there was no "high" culture and "low" culture — just culture…This ideology has become known as "poptimism"…

Poptimism…made mass culture the center of the cultural conversation, which was bound to disappoint us. And, second, poptimist criticism provided a false promise that "creativity" can happen anywhere, ignoring the fact that some creative endeavors and formats are much more conducive to the kind of cultural invention that provides lasting works of art…

The poptimist generation of critics in the 21st century rejected [the] separation of high and low art. They argued that there was no meaningful difference between Mariah Carey and Kurt Cobain…Not every creative endeavor provides the same degree of originality or formalistic mastery. A child's finger-painting is not equivalent to a Rothko. A work only verges towards art in challenging or playing with the existing conventions to create new aesthetic effects. Entertainment…just needs to provide enough stimulus to momentarily keep an audience's attention, and it can usually achieve this by tapping well-tested conventional formulas.

[A]udiences are not so easily fooled…They know when a song is just a jam and not a radical piece of transformative art.

Marx differentiates “art” and “entertainment” based not on their quality, but on the intent of their creators. “Art” is when creators try to push the boundaries of creative expression with new forms and new ideas; “Entertainment” is when creators just want to please the masses. When creators stop trying to make art and just make entertainment, you get a decrease in novelty, because people aren’t trying as hard to push the boundaries — there is no avant-garde.

That’s a reasonable definition, and a reasonable hypothesis. I don’t think things are nearly quite so cut-and-dried — plenty of entertainers work very hard and very creatively to find new lucrative ways to entertain the masses. I highly recommend the book The Making of Star Wars as a window into just how much effort and inventiveness went into the 1977 movie.5 But OK, I do accept that if you have fewer people intentionally trying to create novelty for novelty’s sake, you will probably end up with less novelty.

The question is why creators have moved from art to entertainment. Marx thinks of culture as something autonomous, so he blames the malign influence of “poptimism” for telling people that entertainment and art are the same. But I naturally tend to look for technological explanations.

When I think about the avant-garde, I think about artists making art for other artists. If you make a painting that’s just a bunch of colored squares or splashes of paint on a canvas, an average person might not be able to tell your art from the efforts of a small child. But other artists will know that you’re trying to subvert the paradigm they’ve been working in — to make a statement about what art is. That’s the kind of thing that only one’s artistic peers understand.

Some artists will always want to make things for other artists to see and react to and judge. But I think that in the old days, many did it out of technological necessity.

Discovering good artists in the old days was a very difficult endeavor. Production companies and publishers had to spend a lot of effort scouting around, and then make a guess as to how a creator’s work would perform in the commercial sphere. An easy way to separate the wheat from the chaff was to basically use a peer review system — to use a creator’s standing in the artistic community as a proxy for whether they would sell to a more general audience.

And so many artists tried to impress other artists because they had to — because other artists were always the first gatekeeper of their work. Standing within the artistic community was what got you discovered. When George Lucas pitched a Flash Gordon movie to Fox, the studio told him that it had to be directed by Federico Fellini — a guy they knew as a top arthouse director. (This was impossible, of course, so Lucas made Star Wars instead.)

Fast-forward to the 2020s, and the artistic community has been largely disintermediated. If you want to be a successful commercial creator, the way to get started now is not first to struggle to prove yourself in the closed and cosseted artistic community — it’s to simply throw your work up online and see if it goes viral. If it does, you’re in.

This means that any creator whose goal is to sell out can do so without spending years making art that impresses artists. Of course, some creators still just intrinsically want to impress other artists. But if the money-motivated creators have left the community, there are just fewer people in that community left to impress. It becomes more and more niche and hipster. And there are fewer crossovers from the art world to mass culture, because the people left in the art world are the ones who don’t really care if they get famous and rich.

So if this hypothesis is true, and if you wanted to bring back the avant-garde, how would you do it? One idea would be to follow the university model — to create fairly closed-off spaces where artists live in material equality with lots of public goods. The high baseline standard of living would reduce artists’ need to get rich. And the close proximity of so many artists would make them try to produce novel art in order to impress each other — just like in academia, professors try to impress each other with their research.

I doubt any new institution like this is in the offing; the university model itself is in trouble, and I don’t think the government is going to be willing to fund art schools just so the professors can make cool art.

But that’s the basic principle — if you want more novelty, I think you’ve got to make the artists work for each other more. How you do that, in a world where technology has made artists irrelevant as gatekeepers, is not something I have a concrete answer for. We may simply be in for a long period of artistic stagnation in America.

To sum up, I sort of believe that cultural stagnation is real, but I also think the root of the problem is probably technological — and therefore very hard to expunge.

I had AI (ChatGPT o3) find these examples for me, in case you’re wondering how I’ve incorporated AI into my writing process. I did have to check them thoroughly to make sure I wasn’t mischaracterizing them, as the AI also listed a whole bunch of examples that didn’t say what it claimed they said.

Well, the first one, at least.

Note that when we talk about the toxic effects of social media, we usually talk about network effects that keep users trapped in an ecosystem because everyone else they want to interact with is trapped in there with them. TikTok and other algorithmic feeds just aren’t that. There’s very little interaction between the users. If I show you a video from Instagram Shorts, you’ll be just as entertained as if it had come from TikTok; there’s really no switching cost involved. Algorithmic feeds are really push media — a form of television. They may be addictive, but they probably aren’t network traps.

TV also got a later start, since only recently did technology make it cheap to produce many hours of good-looking TV.

In fact, this is the only “making of” book that I’ve ever recommended to anyone.

Isn’t part of this phenomenon also that technology makes a lot of “old” pop culture much more available than it used to be too? Back when radio and, to a much more limited extent, record shops were tastemakers, there was a focus on new stuff within the mainstream. Radio stations can only play so much and record shops have limited inventories. Similarly, for films you’d have either the cinema or what you could rent in a Blockbuster, again with limited inventories. TV was even more restricted.

Now, however, you can access almost everything with an available master recording if you have a few subscriptions and a smartphone. The tastemakers are also algorithms that have much less regard for what’s new - except for specific playlists or promotions.

I bought my own copy of My Bloody Valentine’s Loveless on CD back in the day. But that was about 20 years after the album was released. I had to hunt around different shops to find it in an era when smartphones and streaming were only just becoming a thing. Now I could find it pretty much instantly if I wanted to, as long as I have a Spotify or Apple Music subscription.

Transgression is critical to cultural development. A new generation must not fear transgressing the boundaries of taste and culture set by the previous. But in today's cultural world transgression can carry with it enormous costs - cancel culture, despite the rise of Donald Trump, is still very real. The incredibly offensive humor and art of the 80s and 90s, the mixing of Disco into Eurobeat to create House music, the mimicry of fashion catwalks to create Voguing etc... would today be met with cries of "cultural appropriation" and/or mockery by the cultural elite.