Why do people get paid to invest their money?

And...should they?

Stocks are up a lot over the past year. If you put $100,000 into an S&P 500 index fund a year ago, you would have about $119,000 now, counting dividends:

That’s not bad, eh? A free 19,000! Of course it’s not technically income — you still have to sell the stock in order to actually use that money to buy anything, at which point you’ll pay capital gains tax. But consider everything you had to do to earn that $19,000:

Press a button that says “buy S&P 500 index fund”

…That’s literally it! That’s all you have to do!

This strikes some people as unfair. After all, the median personal wealth in America is around $112,000, meaning that almost half of Americans don’t even have $100,000 to invest. If you don’t have much wealth at all, then the only way for you to get $20,000 — probably — is to work a bunch of hours. At 19 an hour, that’s 1000 hours — more than half of a typical working year!

That naturally strikes a lot of people as unfair. Why should poor people have to toil away for huge portions of their lifetime, while rich people can make money appear automatically in their accounts with the touch of a button? This is the question of desert (who deserves money), and it’s something a lot of people think about and care about with regards to the economy.

Even if you don’t think making capital income is inherently unfair, there’s a second question, which is: Why do we need that kind of thing for our economy? If people are getting compensated for pressing a button that says “Buy an S&P 500 index fund”, then presumably this button-press must be necessary for our economy somehow. But why?

It’s obvious why we need workers. It’s clear why we need real investment — building machines, structures, vehicles, and so on. It’s obvious why we need entrepreneurs. But why does production depend crucially on some guy pressing a button that says “Buy an S&P 500 index fund”? This is the question of utility, and it’s actually a question of whether there could be a more efficient way to design our economy. (In fact, as we’ll see, this ends up actually being connected to the question of “Who deserves money?” But it’s good to conceptually separate them in our minds.)

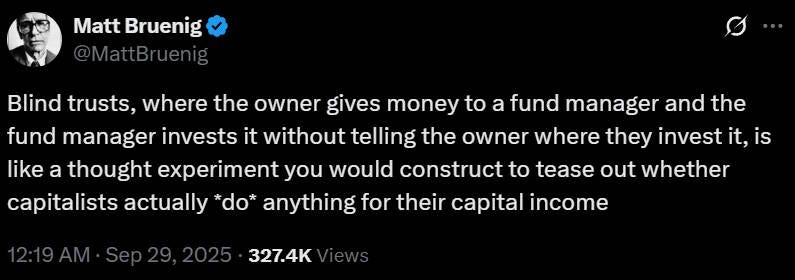

These are very basic questions that we don’t think about very often; capitalist economies are just all set up this way, and they all work pretty well in terms of making the average person rich, so we don’t question it at a deep level. But some people do! For example, Matt Bruenig, the socialist writer, recently wrote:

This touches both on the question of why investors deserve capital income, and on the question of what function investors perform in the economy. So let’s think a little bit about those questions.

What do investors give up in order to get financial income?

In fact, the question of “who deserves money?”, like all moral questions, is subjective. People disagree about this all the time. Some people think welfare is fine, other people think people should work for their money, and so on. There’s no one provable universal answer to the question of whether you deserve to get money by buying an S&P 500 index fund.

But we can simplify this question if we assume some kind of moral principle. And one pretty common principle is fairness. If you get something, it sort of seems fair that you should have to give up something in return.

For workers, it’s obvious what they’re giving up to earn a wage. Work is hard and annoying (otherwise they wouldn’t have to pay you to do it), and it takes up a lot of your time. So the sacrifice involved is clear. But what does an investor sacrifice just by pressing a button?

Well, the first thing they sacrifice is consumption. Investing money is a form of saving, and saving means you can’t consume. If I buy $100,000 of an S&P 500 index fund, it means I can’t spend $100,000 on…um…whatever people spend that much money on. A Lamborghini? Throwing lavish parties? A really really huge amount of Percy Pig candies? Whatever it is, I can’t buy it; in order to get that return on my stock investment, I’ve got to lock up my money for a while.

Locking up my money and forgoing consumption for a year might not be as painful as slaving away behind a cash register for 1000 hours, but it’s not nothing.

But that’s not actually the only thing that investors give up. They also take risk. Stocks usually make money (at least in the U.S.), but sometimes they crash. This isn’t just painful to watch when it happens; it’s also anxiety-inducing at the time you invest the money. When you buy an S&P 500 index fund, you have to wonder if you’re going to need to sell that stock to raise cash — for a medical emergency, or for your daughter’s wedding, or to spend in retirement — at the exact time when the market is way down.

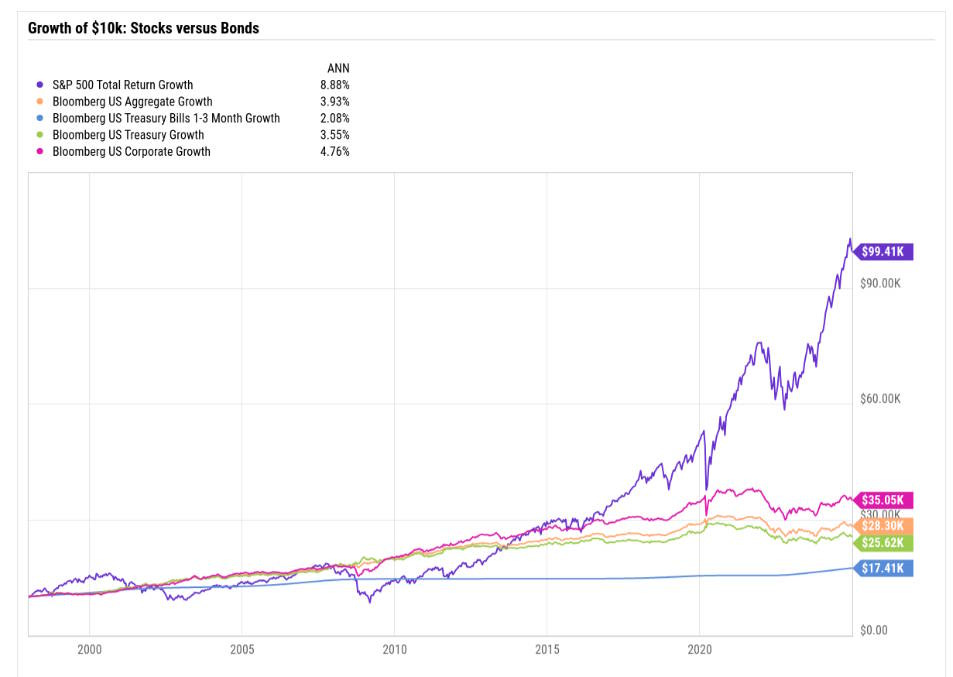

In general, riskier assets tend to give you higher returns. For example, stocks are riskier than bonds, since they tend to crash more often — and crash harder. But over a long time, investing in stocks tends to give you more money than investing in bonds. Here’s a comparison of U.S. stocks (dark blue) vs. U.S. treasury bonds since 1997:

As you can see, stocks actually did worse than bonds between 1997 and 2013 — sixteen years! If a stock investor needed to retire or pay a big medical bill during that 16 years, they were out of luck. But eventually stocks beat bonds. And you can see this same pattern throughout U.S. history (and in most other countries).1

In finance, we call this the “risk-reward tradeoff”.2

The morality of the risk-reward tradeoff can be a difficult thing for some people to wrap their heads around. In a way, risk is inherently unfair; if two people both buy houses on the same block, and one gets flattened by a tree in a hurricane, that’s just not fair. Because of this, some people don’t think that rewarding people for taking risks can possibly be fair. In 2014, in a debate with none other than Yours Truly, Matt Bruenig wrote:

Capitalism does not reward risk-taking…Suppose Noah and I each invest in ways that are identical in all regards with respect to risk. If capitalism rewarded risk-taking, then each of us would get an identical return. But we don’t necessarily. Suppose Noah’s investment leads to him receiving a large return, while mine leads to me receiving nothing and even losing what I put in. In that possible scenario, even though we behaved in a relevantly identical fashion, capitalism distributed us different amounts. Noah was rewarded for risk-taking. I was punished…[T]he lottery-like aspect of investment (risk-taking) is diametrically opposed to the core concept of desert…We can both do substantively equivalent things — invest in asset class with risk level X — and get totally different stuff out of it. Neither of us is anymore deserving of what we get than the other, just as a lottery winner is not more deserving of the prize than a lottery loser.

People on X have recently discovered this quote, and are making fun of it. In fact, Bruenig does seem not to have thought very carefully about what it would mean to be rewarded for risk-taking. If everyone who ever took on a particular level experienced the exact same outcome, then by definition there wasn’t any risk involved. “Risk” means that you might win and you might lose. So Bruenig’s notion of what it would mean for people to be rewarded for risk-taking is logically incoherent.

The fact is, if outcomes have any randomness to them, something that is fair ex ante can’t be fair ex post. You can have fairness before the dice roll, or after, but you can’t have both, because when the dice land, it’s a different world than before they were thrown.

So when people invest in stocks, they’re agreeing to give up consumption and accept risk. Whether or not you think that’s enough to make it fair that investors earn money on average over time is up to you. But that’s what they give up.

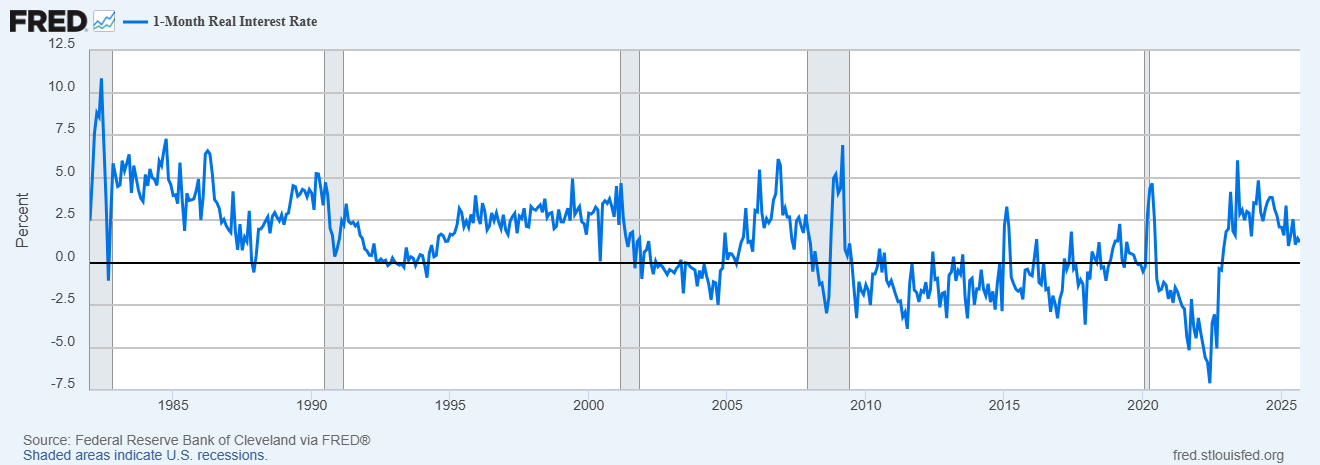

Now, there is one very notable exception. If you invest in a very safe asset (say, U.S. Treasury bills) for a very short amount of time (say, four weeks), then there’s almost no risk and almost no foregone consumption. Right now, you can earn a real return of about 1% annualized by doing this (after subtracting inflation), and in the past you could earn as much as 5%:

That’s basically free money, so it’s hard for me to think of a reason why that’s morally fair.

Why does the economy need financial investors?

I don’t think we’re quite done with the question of “Why do investors deserve financial income?”.

Most of us probably all agree that a worker deserves the wage they earn. But it’s not just because they worked hard to get it. Going to the gym is hard work, but we don’t generally think people should be paid to go to the gym. Sitting around doing sudoku is hard work, but we don’t generally think people should be paid to do sudoku.

Workers don’t just sacrifice; they also produce something. Thanks to their actions, stuff exists that wouldn’t otherwise exist. So in some sense, we probably think of productivity as a necessary component of “deserving money”.

Which brings us to the question of whether buying an S&P 500 index fund is actually productive.

The answer to this one, unfortunately, is “We don’t really know.” The reason is that we don’t know exactly how the economy works. There are a lot of steps between “guy pushes a button to buy an S&P 500 index fund” and “the economy produces more useful stuff”, and we don’t know for certain what all those mechanisms even are, much less whether they’re working as they ought to.

For one thing, we don’t actually know how financial decisions affect the real economy. Theoretically, if a company’s stock is worth more, they should do more capital expenditure — if I can sell a share of my stock for $1000, I can finance the purchase of machines or office buildings or delivery trucks much more easily than if I can only sell that share for $10. In practice, it’s not so clear how much this actually matters. As far as we can tell, stock price seems to matter somewhat for businesses’ investment decisions, but it’s not the only thing going on. There are plenty of complicating factors, including A) the fact that companies use debt and their own cash flows to fund themselves in addition to stock sales,3 and B) the fact that it’s not always clear when companies are purchasing capital, since some capital is “intangible”4 and thus very hard to observe.

We also don’t understand the feedback mechanism, by which real economic activity changes asset prices and gives investors a return. Just how much stock prices go up when a company grows and earns more is a perennial debate in economics.5

On top of all that, we don’t even know how an investor’s decision to buy stocks affects stock prices themselves! If I buy $100,000 of an S&P 500 index fund, how much does the S&P 500 actually go up? The answer isn’t “$100,000”. Stocks are not like containers of liquid that hold wealth; instead, prices are determined by how much the people who trade stocks on any given day (or hour, or minute) agree to buy and sell the stock for. The price impact of stock purchases can vary depending on a lot of things.

So a lot of what we have here are theories, rather than well-established empirical facts. In theory, financial investment does two things for the real economy:

It determines how much of the economy’s overall resources to allocate toward risky business projects, and

It determines which risky business projects deserve to be allocated more resources.

The second of these is called asset allocation. If Microsoft can earn more from building data centers than Google can, it’s because Microsoft is doing better at AI. All else equal, that means I should buy Microsoft stock and sell Google stock. And if I do that, it’ll be easier for Microsoft to finance the building of new data centers, and harder for Google to do so. So Microsoft will build more, and Google will build less.

That’s the theory of how smart asset allocators direct real capital to where it needs to go. In fact, we see plenty of examples of finance people trying to do something along these lines in real life. We see venture capitalists funding startups, hedge fund managers evaluating companies to see which stocks will do well, and so on.

But also, there are a lot of people who don’t put any effort or intelligence into picking their assets. If you just press a button that says “Buy S&P 500 index fund”, you’ve just copied the market exactly. This is very often a rational move, because most people don’t have any information about which stocks are undervalued and which are overvalued. But it doesn’t actually make prices more “right” — it just keeps them the same. So it can’t shift real capital from worse companies to better companies.

Essentially, when you press a button that says “Buy S&P 500 index fund”, the only thing you’re deciding — if you’re deciding anything at all — is that stocks, in general, should be more expensive.

That’s not nothing, though. It’s a vote of confidence in American business in general. It’s saying that American businesses in general have good opportunities and should invest and expand, even if you don’t presume to know which companies have relatively better prospects. If stock prices affect business investment, then your purchase of an S&P 500 index fund will increase American business investment.

If you think about it, this probably is part of the reason you buy an index fund. Sure, to some extent it just happens to be your payday.6 But also, you would probably be afraid to buy stocks if you thought American business was going to do badly.

In other words, even investors who don’t bother doing any asset evaluation or allocation might be adding some useful information to the market when they buy stocks. Perhaps the long rise of the U.S. stock market and the long smooth arc of American economic growth were not unrelated phenomena — perhaps they were both simply a long string of wisely optimistic bets on the potential of American business.

So although it’s not certain, we can definitely see a possible way that letting investors turn money into more money with the touch of a button might be good for the economy. Which means that although pressing a button that says “Buy stocks!” might seem like a useless no-brainer, it might actually be contributing to the efficient functioning of the American business world — and, thus, to greater output.

None of this is to say, of course, that the amount of income that investors have gotten from U.S. stock markets has been either fully fair or fully efficient. U.S. stocks in particular have done insanely well for the past century or so, usually doubling investors’ money every 10 years (even after accounting for inflation). That’s a huge amount of financial reward for something as passive as buying and holding an index fund. In fact, economists still argue vigorously over just why stocks have done so well.

And none of this is to say that government has no place in the capital allocating world. Sovereign wealth funds, policy banks, government influence over the banking system, industrial subsidies, and corporate taxes are just a few of the many ways that the government influences the allocation of financial capital in a modern economy. And the government allocates real capital directly just by doing things like building infrastructure. None of what I’ve said means that these government efforts are inefficient, or should be minimized. In fact, it’s possible that scaling them up dramatically — as China has recently done — would be a good idea. Or maybe not.

My point here is that there are pretty clear reasons why lavishing wealth on people for simply pushing a button labeled “Buy stocks!” could be both moral and good for the economy. That’s a weird thing to realize, but it’s true.

Whether this pattern holds between different stocks is actually an open question, because the relative riskiness of stocks is hard to measure. This is because some of the apparent risk of individual stocks is basically fake; you can get rid of it by diversifying your portfolio. But exactly how to diversify your portfolio, and whether it’s possible to know in advance how best to diversify, is one of the biggest open questions in finance.

Some people call it the “risk-return” tradeoff instead, but I don’t like this terminology. Sometimes that “return” doesn’t actually happen. Instead, it’s actually a tradeoff between risk and long-term expected return. But “long-term expected return” is a mouthful to say, and “expected” has a very specific statistical meaning in this case that a lot of people misunderstand, so I prefer the word “reward”.

These three financing methods are only equivalent in some highly idealized conditions that typically don’t prevail in the real world.

This includes things like brands, ideas, internal organization, human networks and relationships, and so on.

Also notice that the two big questions — how asset prices affect business activity, and how business results affect asset prices — are very hard to answer at the same time, since there is obviously a feedback effect at work here, meaning you have to measure two different directions of causality at once.

This is what’s known as “liquidity trading”.

The scenario you led with was clearly designed to be invidious ("rich guy with $100K lying around to spend on a Lamborghini or invest") but a lot of investors are ordinary people putting away money for retirement or contingencies. At least to me it is entirely "fair" that such investors have an upside for deferring consumptions for years or decades.

Also, as to the free 1% from "risk free" t-bills: you left out taxes. After tax, any high-income investor is lucky to not lose purchasing power if they only invest in t-bills or munis. And that's before assuming the risk of a rapid devaluation.

It always makes me queasy when people talk about "fair" because the term is so subjective. I'm glad you mostly focus on the policy question of how investment affects the economy and society.

Might be worth noting that when I buy a share of stock my money doesn’t go to the company, unless I’m buying from the company in an IPO or subsequent offering. Usually my money goes to someone who owns a share and wants to sell. So I’m usually not investing in the company. The existence of a trading market in company shares does assist the company in raising capital by setting a market price.