When are tariffs good?

National security, infant industries, national champions, and some more unorthodox theories.

The threat of U.S. tariffs on Canada and Mexico seems to have abated for now. Both countries made largely symbolic commitments to border security that convinced Trump to delay the tariffs for one month. This makes it seem likely that the tariffs could be delayed again, or canceled entirely. This is the least bad outcome. But although much of the world is breathing a sigh of relief, the mere knowledge that Trump could change his mind and implement tariffs on America’s key allies and trading partners at any moment will exert a chilling effect on business investment. Bloomberg reports:

Over a frantic 72 hours, President Donald Trump’s threat of punishing new tariffs on Canada, Mexico and China…sent manufacturing businesses scrambling for cover…Even after the president put a one-month hold on the Mexico and Canada duties on Monday, executives are still very much on watch for additional tariffs…

It was…frantic for Randy Carr, who runs World Emblem, the biggest global manufacturer of emblems and patches…“We have had to suspend every capex project we have for the next 24 months until we better understand the trade situation,” Carr said…World Emblem also paused hiring plans, said the executive, whose company has 1,300 employees between production bases in the US and Mexico. “It’s reminiscent of the adjustments we had to make during Covid-19.”

Tariffs help domestic manufacturers by protecting them from foreign competition, but they hurt them by driving up the cost of their imported components. This is one of the two big problems with tariffs — the other one being that they drive up consumer prices.

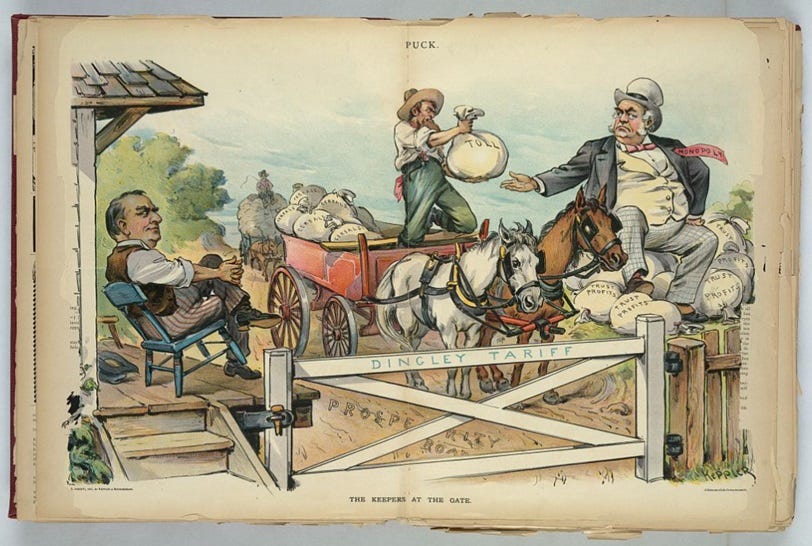

But does this mean tariffs are always bad? Many people — even some Democrats who are usually skeptical of libertarian arguments — responded to Trump’s chaotic tariff announcement by extolling the benefits of free trade. But after decades of deindustrialization, such purist arguments are unlikely to carry much weight. There’s a general sense that free trade was a sucker’s bet for America, and any ideological blanket denunciation of tariffs is going to run up against that deep reservoir of (somewhat justified) anger.

In fact, there are some reasonable arguments for when tariffs might be helpful. Economists have known about these ideas for centuries, and there have been many papers written about them. Because economists tend to be overly attached to the idea of free trade, the justifications for tariffs rarely come up in public conversations.

So I thought I would go through a few of these. But note that all of them are arguments for targeted tariffs, instead of the broad, across-the-board tariffs that Trump threatened against Canada and Mexico.

National security concerns

The most important justification for tariffs, as I see it, is national security. If a war breaks out between the U.S. and China, the U.S. will have to build a whole lot of munitions and weapons very fast — especially drones, ships, missiles, and so on. In order to do that, it’s incredibly important to have existing civilian industries that can be quickly repurposed for military purposes — just like auto companies built bombers and tanks in World War 2.

If a country’s manufacturing base shrivels up and dies, it won’t be able to fight a protracted conventional modern war against a peer adversary. To name just one example, if the U.S. finds itself without battery factories — either on its own territory or on safe nearby territory — it won’t be able to make the FPV drones that have become the standard weapon on the battlefields of Ukraine. That could be disastrous. Thus, it is important to maintain some battery manufacturing capacity in the U.S., Canada, and/or Mexico.

Now, Xi Jinping knows this. If he wants to weaken the U.S. — as he almost certainly does — one thing he can do is to try to crush American manufacturing industries by outcompeting them with targeted surges of cheap exports. It’s quite possible that this is one motivation behind China’s sudden surge of manufactured exports, which is being promoted with below-market bank loans, government subsidies, and a host of other policies.

Tariffs are a defense against this forced deindustrialization strategy. If Xi suddenly decides to flood America with cheap Chinese batteries, the U.S. can respond very quickly by raising tariffs on Chinese batteries, canceling out the effect of China’s subsidies. In fact, this is what Biden did last year, when he levied very high tariffs on a variety of China’s strategic industries.

But note that Trump’s proposed tariffs on Canada and Mexico don’t fit this strategy at all. Most importantly, putting tariffs on U.S. allies doesn’t guard against forced deindustrialization by China; in fact, it makes the problem worse, by disrupting North American supply chains and raising costs for U.S. manufacturers.

It also makes the U.S. dollar appreciate, making American exports less competitive. This is a general reason why targeted tariffs like Biden’s are more effective than broad, across-the-board tariffs like the ones Trump is threatening:

In fact, dollar appreciation is exactly what happened in 2018-19 after Trump’s initial tariffs, and it’s exactly what’s happening now:

So if you want tariffs for national security reasons, Trump’s proposed tariffs on U.S. allies are exactly the wrong kind.

Our companies vs. their companies

Economists don’t typically think about national security; instead, they tend to think good policies are those that produce more growth, more employment, and so on. And if those are your objectives, there are definitely still some reasons why tariffs might be a good thing — at least, from a single nation’s perspective.

The most common reason is all about national champions. Real-world markets aren’t perfectly competitive — some big companies make a ton of profit, by leveraging what economists call increasing returns to scale. Increasing returns to scale are just anything that gives big companies a cost advantage over smaller ones — maybe network effects, or big fixed costs, or a “superstar” effect that draws in top talent, etc. In a world of increasing returns, the winning companies make a lot of profit, and smaller companies don’t.

A country might therefore be able to increase its wealth by using tariffs to guard its own “national champion” companies. Basically, the idea is to use tariffs to reduce the scale of foreign companies by denying them your domestic market. This will allow your own country’s national champions to outcompete their overseas rivals, which means they’ll capture more of the profit to be had in the market. This is called “strategic trade” policy.

James Brander and Barbara Spencer pointed out this argument for tariffs back in the 1980s. Paul Krugman, who helped develop the leading theory of increasing returns and trade, summarized their work on this topic in 1987:

A country can raise its national income at other countries' expense if it can somehow ensure that the lucky firm that gets to earn excess returns is domestic rather than foreign. In two influential papers, James Brander and Barbara Spencer…showed that government policies such as export subsidies and import restrictions can, under the right circumstances, deter foreign firms from competing for lucrative markets. Government policy here serves much the same role that "strategic" moves such as investment in excess capacity or research and development (R & D) serve in many models of oligopolistic competition—hence the term "strategic trade policy."…[A]t least under some circumstances a government, by supporting its firms in international competition, can raise national welfare at another country's expense.

In fact, there’s some evidence that free trade can make a country poorer by destroying its national champions. This is from Sampson et al. (2022):

Import liberalisation brings down import costs and increases competition. But with scale economies, import liberalisation can also reduce the productivity of domestic industry by shrinking its scale, leading to lower exports. As this column shows, evidence from the permanent normalisation of US trade relations with China in the early 2000s reveals that increased Chinese import competition indeed reduced US exports through this channel, implying the presence of industry-level scale economies in the US.

The implication here is that if the U.S. had used tariffs to protect certain very oligopolistic industries from Chinese competition back in the early 2000s, America would have been a bit richer.

But again, this argument for tariffs doesn’t apply to Trump’s recent efforts. First of all, it only applies to industries where there are only a few winners, and thus a lot of profits to be made. That implies, again, that targeted tariffs are the way to go. Broad, across-the-board tariffs will dilute the effect, through exchange rate appreciation. Trump would have put tariffs on agriculture — a highly competitive industry where there are very few profits to fight over. This approach just doesn’t fit the theory of strategic trade.

Second, if you want your national champions to be able to scale up, you probably don’t want to start a trade war with your most important allies and trading partners. They will almost certainly retaliate, denying market access to your own top companies. Canada and Mexico would probably resort to retaliatory measures if their efforts to buy off Trump with symbolic concessions failed. This would limit markets for America’s top companies, and hurt them in their competition with Chinese rivals.

And finally, if you want to increase your national champions’ scale, you can probably get a lot more mileage out of export subsidies than tariffs. Tariffs can hurt national champions by denying them access to cheap production inputs; export subsidies, although they cost more in fiscal terms, don’t have this problem.

Infant industry protection — the American way

A lot of people have asked me to address the pro-tariff arguments in this recent blog post by Anthony Pompliano:

Some of Pompliano’s arguments in this piece are simply bad. For example, he cites the factory construction boom and the reshoring of the solar industry as examples of American industrial successes driven by tariffs. But in both of those cases, while tariffs might have been a significant factor, we didn’t really see much progress until Biden unleashed industrial policy with the CHIPS Act and the Inflation Reduction Act.

Pompliano also argues that tariffs are less distortionary than income taxes, which is generally true if you’re talking about the same tax rate. But if you’re talking about raising a set amount of revenue from either income tax or tariffs, then the tariffs are almost certainly much worse. This is because tariffs are a lot easier to avoid than income taxes; you just buy similar products made elsewhere. Because tariffs are relatively easy to avoid, they don’t raise a lot of revenue. And so if you want to use tariffs to raise, say, $1 trillion a year for the U.S. government, you’re going to need to set the tariff rates very high. And that will be very distortionary.

But anyway, Pompliano’s strongest argument is that tariffs for infant industries were useful for America’s economic development back in the 19th century:

Tariffs are widely credited as an essential tool for the success of the Industrial Revolution, which created the American economy we know today…Historical figures like George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, Henry Clay, James Monroe, Abraham Lincoln, William McKinley, and Theodore Roosevelt were all outspoken supporters of tariffs as a necessary tool for America to thrive. The famous Lincoln quote on tariffs is “Give us a protective tariff, and we shall have the greatest nation on earth.”

This is what economists call an “infant industry argument”. Basically, American leaders in the early days of the republic wanted to promote the creation of new industries in the U.S. Alexander Hamilton wrote his famous Report on Manufactures in 1791. He argued that tariffs would allow domestic champions to achieve sufficient scale to compete with foreign companies — very consistent with the strategic trade theory that would be developed a century later. Hamilton also argued that sheltering new American industries from competition would give them time to learn more about how to compete with established foreign rivals.

Infant industry arguments are certainly plausible in some cases — Pompliano certainly exaggerates when says that tariffs built America, but they probably did help some key American industries get off the ground instead of being replaced by floods of British imports.

But here too, the specifics of Trump’s plans are at odds with the economics. Once again, the economic argument is for targeted tariffs in very specific cases — in this case, new industries facing competition from big foreign incumbents. Trump’s across-the-board tariffs are almost entirely targeting non-infant industries. (Also, in general, import quotas are more helpful for infant industries than tariffs.)

Two more speculative arguments

So those are the three basic arguments in favor of tariffs — national security, national champions, and infant industries. All of them are pretty solid arguments, though they all imply that Trump’s preferred approach to tariffs is highly suboptimal. But there are some other interesting arguments about tariffs floating around, which deserve a mention.

One of these is Michael Pettis’ theory that tariffs on China will help to correct global trade imbalances, and could force China to change its economic model to a more consumption-focused one. I wrote about this idea here:

Basically, I think this makes sense as a China-specific political-economic argument. The idea, I think, is that if tariffs force Chinese companies to focus more on their domestic market, then Chinese companies will quickly become unprofitable (due to overproduction and over-competition). This unprofitability could prompt China’s government to reduce their subsidies for industrial overproduction. That’s my personal interpretation of Pettis’ ideas, and I’m not sure how plausible it is, but it’s certainly an interesting thought. I would note, however, that this is a purely China-specific idea, rather than a justification for tariffs on Mexico and Canada.

Another theory, courtesy of Sam Hammond, is that tariffs are the first step in a forced de-dollarization of the global economy:

I think there's a p(=30%) chance that we are instead witnessing the first (albeit somewhat clumsy) phase of a deliberate strategy for controlled de-dollarization…By imposing universal tariffs, the US intentionally undermines the stability of the dollar as a trade currency and signals that global partners can’t rely on “business as usual.”…This short-term shock (“raising entropy”) is precisely the point: disruption forces other countries to reduce dollar holdings or consider alternative reserve arrangements, setting the stage for a monetary reset.

I don’t put much credence in this theory. The reason, as I’ve explained a number of times, is that tariffs make the U.S. dollar more expensive, not less.

So anyway, I think national security, plus the classic economics justification for tariffs — strategic trade and infant industry protection — are still the best arguments in favor of tariffs. And all of them cast doubt on the kind of tariffs Trump is threatening to do. Even if some kinds of tariffs are good in some situations, Trump’s threatened tariffs on Canada and Mexico are extremely unlikely to be those.

Noah, I'd love to hear more about what capacity the USA and Europe have for local drone manufacturing. What kinda volumes are the USA and Europe hitting? What could the USA hit if shit hits the fan? What was Ukraine able to spin up and how fast?

I believe the USA has had a block on the big Chinese drone firm for a while, has that helped spur local manufacturing?

How should other countries respond to threatened tariffs? The same 25% tariff right back? What would be the consequences of this vs alternatives? Tariffs don't exactly cancel out. What could/should both governments then do with the tariff revenue....