What if local control can actually help build housing?

Some places want to build. Maybe we should just let them.

I am a well-known proponent of the YIMBY movement, which wants to build more housing in America. Essentially all of the economic arguments against greater housing density are wrong; it really just comes down to personal preference. And the United States would be far better served by having a variety of different urban landscapes — dense Manhattan-like cities for people who want to live in dense cities, leafy sprawling suburbs for people who like suburbs, and then everything in between. Right now we have only one real dense walkable big city (NYC); this deprives much of the country not just of the opportunity to live how they like, but also of the economic benefits that come with density.

The big question about denser housing development is not “Should we do it?”. The answer to that question is “Yes.” The question is: How can we get it done, politically speaking?

As things stand, there’s a broad understanding that the obstacle to building more housing is local control. A few NIMBYs who don’t want to build housing show up to planning meetings and zoning board meetings, bring lawsuits, and otherwise make a bunch of noise and punch above their weight, resulting in the tyranny of the local minority. For example, Einstein, Palmer, and Glick (2018) look at who shows up to local meetings, and find that NIMBYs are very overrepresented:

[W]e compile a novel data set by coding thousands of instances of citizens speaking at planning and zoning board meetings concerning housing development. We match individuals to a voter file to investigate local political participation in housing and development policy. We find that individuals who are older, male, longtime residents, voters in local elections, and homeowners are significantly more likely to participate in these meetings. These individuals overwhelmingly (and to a much greater degree than the general public) oppose new housing construction.

Other researchers find much the same thing.1

Most YIMBYs have a simple solution to this problem: Make authority over housing less local. A few NIMBYs might be able to dominate each local planning board, but even all together they’re less capable of bullying a state legislature. The notion here is that individuals simply have outsized power at the local level, where showing up is what matters most, while the silent pro-housing majority can simply vote to overrule the loudmouth NIMBYs at the state or national level.

Alan Dunning explains the idea:

The political theory behind this strategy is that by taking the campaign to a larger arena, advocates can draw in a vast and rarely assembled coalition: displaced and would-be urban residents, affordable housing providers, major employers and unions, chambers of commerce and economic development agencies, and advocates for everything from racial and social justice to economic opportunity to climate sense to private property rights to transit improvement to children’s health to homelessness services. These interests have a lot to gain from abundant housing, but they lack enough incentive to expend political effort in thousands of jurisdictions in countless local land-use planning processes. Only the obstructionists are widely distributed enough to engage in that conventional process. By enlarging the fight, pro-housing forces can dilute the excess influence that these housing-shortage deniers and home-building obstructionists hold in city politics.

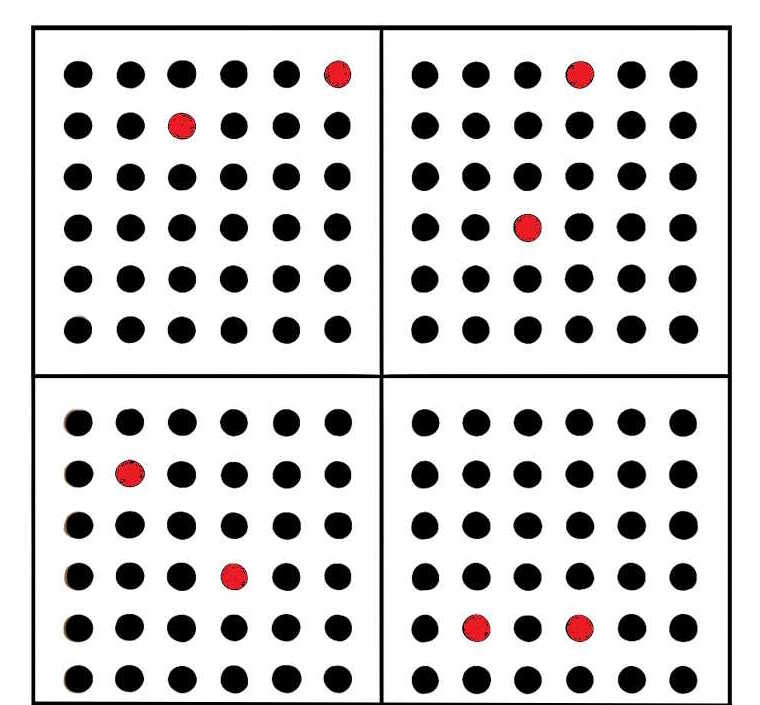

Here’s a schematic of what this looks like. Suppose a state is divided into four cities. Each dot represents a citizen, and each red dot represents a local NIMBY:

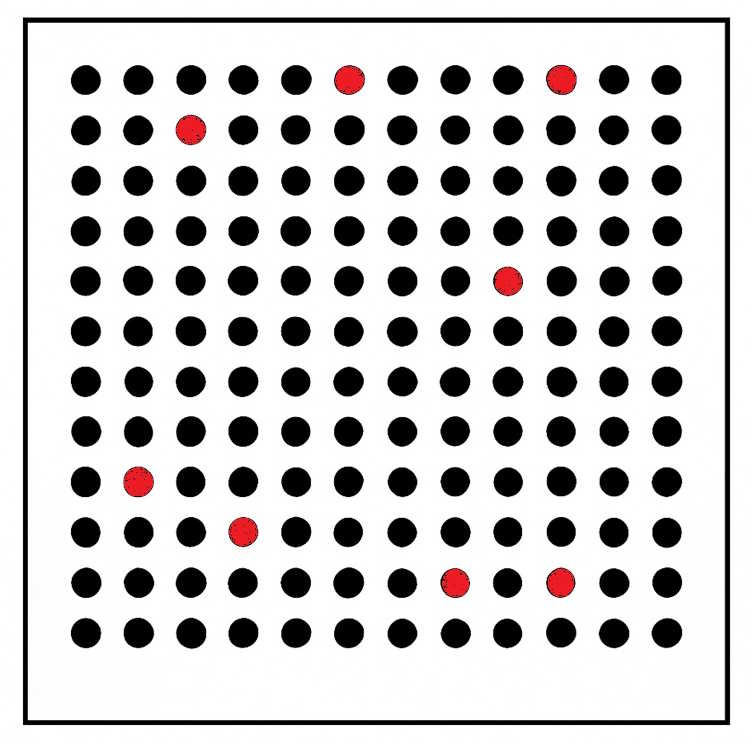

Since showing up to local meetings is effective at the city level, none of the 4 cities in this diagram gets any housing, because each city has 2 NIMBYs. But now remove the lines, so that we’re looking at things at the state level:

At the state level, housing is decided by majority-rule elections rather than by showing up to meetings. So the normal folks (the black dots) easily overrule the less numerous NIMBYs, and housing gets built throughout the state.

There is some evidence that this approach can work in the real world. For example, Mast (2022) finds that when city council members are selected by citywide elections rather than at the neighborhood level, a city gets substantially more housing permits:

I study how increased local control affects housing production by exploiting a common electoral reform—changing from “at-large” to “ward” elections for town council. These reforms…shrink each representative’s constituency from the entire town to one ward. Results from a variety of difference-in-differences estimators show that this decentralization decreases housing units permitted by 20%[.]

Anecdotally, countries where the national government exerts a lot of control over housing rules often tend to build more housing. For example, Japan’s nationalized zoning rules are often credited with that country’s tendency to build more dense housing. And France’s national government forced cities to build more housing in the 2000s:

France is a unitary state, where all power resides in the national government unless specifically delegated elsewhere…Consequently, the French President and Parliament exert much more control than their North American counterparts. The French Parliament, for example, sets building and land-use codes…

Twelve years ago, then-President Sarkozy proposed encircling every new Grand Paris subway station with a mile-wide neighborhood of taller apartment buildings. Although the audacious proposal was rejected by Parliament, most localities are now implementing it anyway. Thus, 70,000 new homes are slated for construction within Sarkozy’s mile-wide station circles.

Centralization allows France not only to mandate housing rules but also to hold localities accountable for achieving housing goals. It can and does bring the hammer down on obstructionism. Local representatives of the national government can impose fines on localities, overrule local zoning plans that are too restrictive, or even seize land and transfer it to developers for additional housing construction. Such actions are rare, but the threat of them keeps most municipalities in line.

YIMBYs in America have tried to do something similar, only at the state level instead of the national level. In California, for instance, Governor Gavin Newsom has used a law called RHNA — which requires cities to submit feasible plans for building more housing, and threatens them with deregulation if they don’t — to force cities to accelerate approval of housing. And the California state legislature has passed a number of laws — most recently, a bill called SB79 — to force cities to allow more housing near transit hubs.

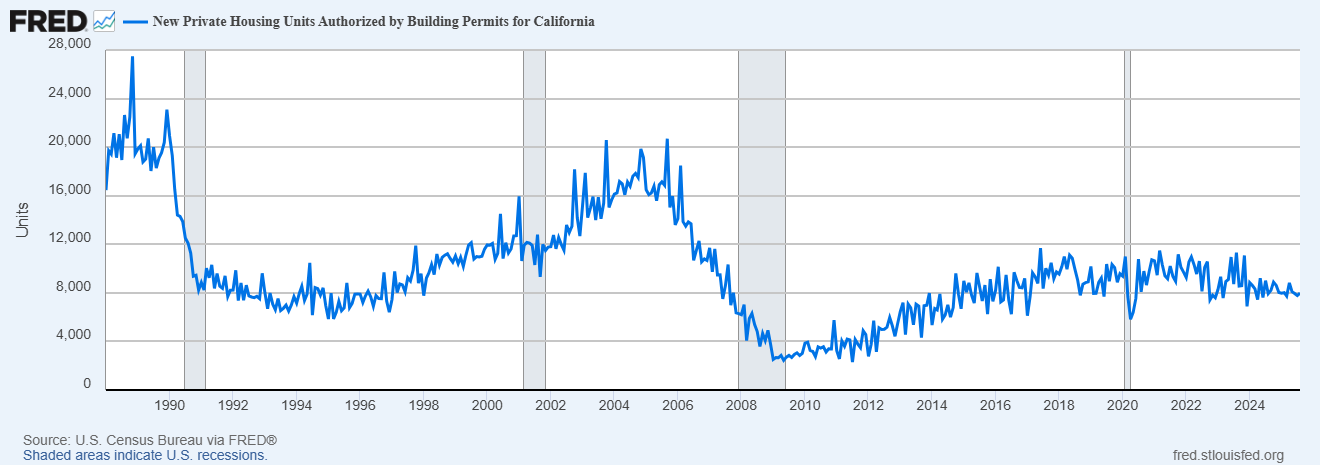

The approach is promising, and it may yet work. But so far, local obstructionism has won out. Local governments have a huge variety of tools at their disposal to block new housing, and the state government often finds itself playing whack-a-mole. Progressives have also larded down the housing bills with “everything-bagel” contracting requirements, which often make it prohibitively expensive and difficult to build housing even if it’s legally allowed. And national factors like high interest rates have been unhelpful. As a result, California isn’t building more new housing:

YIMBYs and state legislators should definitely double down and keep trying. But it may be time to develop a second approach in parallel.

In recent years, some cities like Houston, TX and Arlington, VA have succeeded in building more housing even without state intervention. There have been two really good articles in Works in Progress about these successes. Anya Martin writes about how Houston did it:

[O]ver the last 25 years, without the rest of the world noticing, things [in Houston] have been quietly changing…The city has become a little more walkable. Pleasant rows of townhomes have appeared in the suburbs, alongside amenities like new parks, restaurants and entertainment, and light rail. Housing has remained remarkably affordable and accessible, even as the wider economy boomed and the population rose drastically…

It’s sometimes said that Houston has ‘no zoning’…but it is not strictly true… Houston’s Code of Ordinances – its planning rulebook – sets limitations like minimum lot sizes (how big a plot of land must be used for each residential property), how far the building must be set back from the street, requirements for the number of parking spaces that must be included with the development, and much else. Historically, this set of regulations, which require a lot of land for each property, combined with the city’s permissive attitude to building outwards, led to Houston’s characteristic sprawl…

In 1998, a major change was made to the Code of Ordinances. The minimum lot size of a plot within the I-610 motorway which circles Houston’s inner suburbs was dropped from 5,000 square feet…to 1,400. This allowed landowners to divide (or ‘replat’) existing lots into much smaller parcels….[N]ow [landowners] could build three homes, for three times as many families…The reforms have survived to this day…

The immediate impact of these changes was a boom in a new style of development that has transformed some of Houston’s inner neighbourhoods: Houston townhomes…Emily Hamilton estimates that almost 80,000 townhomes have been developed owing to the changes; all using previously developed land, and in the types of central locations where it is usually most difficult to build…Some of Houston’s neighbourhoods were totally transformed. Rice Military…built up rapidly and is now a vibrant area known for attracting young creative types and having good walkable access to restaurants, bars, and parks…Houston, synonymous in many people’s minds with car-centric America, is now mid-ranked among American cities on the Foot Traffic Ahead walkability ranking, with its substantial improvement acknowledged in the latest report. In the 1990s it was the only major city in the United States without a rail system; it now has three light rail lines operating and two more planned.

This sounds like a victory for centralized government. But that leaves the question of why Houston’s government was able to go YIMBY so easily, without provoking a NIMBY backlash. Martin argues that Houston defused the NIMBYs by allowing NIMBY neighborhoods to opt out of the citywide upzoning:

[G]enerally, existing homeowners form a powerful interest group who apply pressure to their local governments not to permit more building in their area…So why was Houston able to pass these reforms?…What most makes Houston different is that it had an in-built system to allow residents of small geographic areas to opt out of citywide zoning rules, and of changes to those rules. This opt-out system may explain why city-wide reforms were able to pass, and why they have had the staying power to last several decades relatively uncontroversially…

[M]any rules around land use [in Houston] are set within private ‘deed restrictions’. These are private agreements between landowners within blocks or small areas…Houstonian homeowners [have always] had an institutional mechanism if they wanted to prevent new types of development near them…If they didn’t want smaller lots to be permitted in their area, they could agree collectively…to add new deed restrictions…In 2001, new legislation was passed to make opting out even easier, by allowing local homeowners to petition the city to introduce a special minimum lot size (SMLS) even without going through the legal process of altering the deed restrictions. These are restrictions which limit new developments to the prevalent lot size, by block or by area. For example…5,000 square feet can be established as the minimum lot size, keeping new developments in the area restricted to large detached homes…

As a result, Houstonian homeowners who really don’t want new homes built near them don’t need to worry as much about the overall citywide rules. They have a much easier route nearer to home: they can agree with their neighbours in the HOA to alter the deed restrictions, or they can petition for a special minimum lot size…This opt-out system is probably the main reason the 1998 reforms were able to pass in the first place…Houston’s system allows homeowners to opt out without bringing housing supply in other areas down with them. [emphasis mine]

In other words, Houston made local control even more local. If a neighborhood doesn’t want to densify, it doesn’t have to. NIMBYs who wanted quiet, leafy neighborhoods full of single-family homes didn’t have to go to city planning board meetings and block housing throughout Houston; they could just block housing in their little local neighborhoods, and be satisfied. Meanwhile, the neighborhoods without many NIMBYs just built more housing, because nobody was trying to stop them.

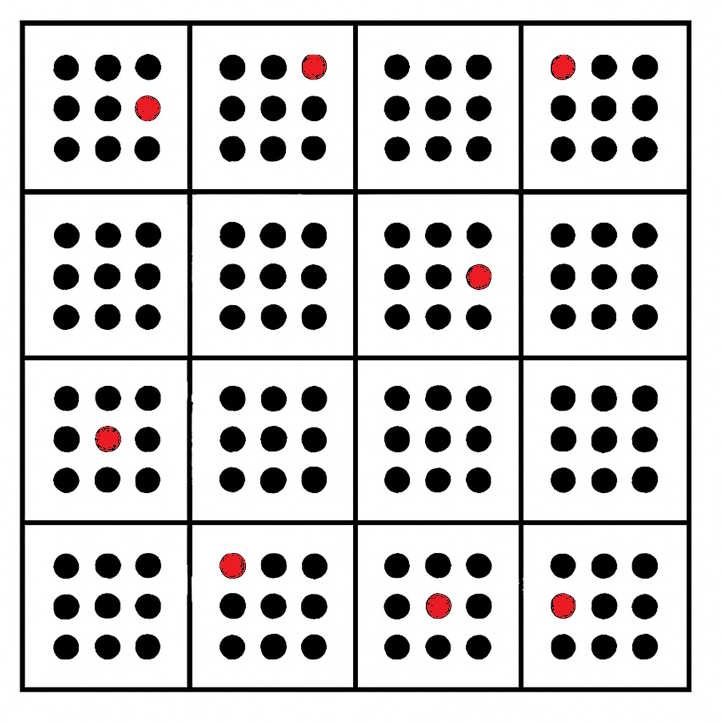

Here’s a diagram of what this hyper-local control looks like, using our example of the grid of dots from above:

Here, every little square is a neighborhood. Every square without a red dot builds housing, and every square with a red dot blocks housing. As a result, housing gets built in half of the neighborhoods.

That’s not as good as forcing housing to be built in every neighborhood, but it’s not bad! It basically fulfills the dream of Americans being able to choose which kind of place they live in — even if they live in the same city. And it may be much more politically palatable than trying to use the hammer of big government to force every city to allow density in every neighborhood at once.

In another Works in Progress article, Emily Hamilton describes Arlington, Virginia’s successful attempt to build more housing. Although it doesn’t have the formal neighborhood opt-out mechanism that Houston has, Arlington basically made a bargain with some neighborhoods not to densify them:

In Arlington, the leafiest and quietest parts of the county remain reserved for single-family zoning…[T]he county carved out some single-family neighborhoods where residents didn’t want to see land-use changes from upzoning…And the [upzoning] plan wasn’t carried out universally: the area around the county’s westernmost Metro station, East Falls Church, is zoned exclusively for low-density development.

Largely this is due to reluctance among local homeowners. But Arlington planners have been careful to work with the grain of homeowner interests where possible…By generally limiting upzoning to areas without homeowners, unless those homeowners have consented, Arlington has permitted much more development than other expensive cities without huge blowback from homeowners.

In fact, hyper-local control may even be a factor in Japan’s willingness to build housing. In a third Works in Progress article, Anya Martin writes about how Japan’s government generates local buy-in for “land readjustment” plans that divide land up into smaller parcels and create greater density:

There are two core mechanisms inside land readjustment, both of which work by generating public legitimacy for major change. The first is sharing the proceeds of the redevelopment evenly. The second is requiring that a large majority of affected residents support the change…If two thirds of affected landowners agree to the scheme, then it is sent up to the governor of the prefecture, which almost always gives approval when a large majority of land- and homeowners support the scheme…

Land readjustment illustrates a general rule of political economy: it is possible to build legitimacy for massive changes, including demolishing many people’s homes and dramatically changing the character of an area, if the benefits of doing so are shared, and if those most affected are seen to have opted for the change.

In other words, Japan may not be an example of big government simply generating the political will to crush the prerogatives of locals and force them to accept density, as some Western urbanists have assumed. Instead, it may be another example of hyper-local control — not quite the same as Houston or Arlington, but sharing the basic feature of giving control over housing to small neighborhoods.

Hyper-local control blends attractive features of both individualism and collectivism. It frees many landowners to build on their properties without being vetoed by faraway NIMBYs on the other side of the city. But it allows the residents of each small neighborhood to come together to decide what the character of that neighborhood should be.

“Local control” has understandably become a dirty word among YIMBYs. But anyone who wants to build more housing throughout America should take a look at hyper-local control as an additional way of getting around the political obstacles to densification. It may be possible to win bruising battles at the state level and force cities to accept density, and I don’t think that effort should be abandoned. But in the end, devolving decisions about density from the city level to the small neighborhood level may be a quieter, more effective path to achieving the same objective.

Cuttner et al. (2024) do argue that this NIMBY overrepresentation can actually help housing get built, by allowing developers to identify the NIMBYs so that they can politically marginalize them.

How about we divide your grid up even further, so each square has one dot in it?

The localest possible control is to let people do what they want with their own land.

Our crisis level lack of affordable housing at the same time we actively pursue foreign immigration is an issue that feeds nativist populism.

And so there is a fundamental principle of social cohesion and stability at stake

We desperately need to promote innovative YIMBYism.

I'm encouraged Noah and other abundance thinkers are on the case.