Note: I’ll be traveling from the 24th through the 28th, so expect posting to be a bit lighter during those days.

Back in the early days of my first blog, I used to encounter a British guy who went by the pseudonym of “Unlearning Economics”, who is now a YouTube pundit. His criticisms of econ were very standard, well-worn British socialist stuff (if you follow British econ debates, which I do not recommend, you’ll know exactly what I’m talking about). But his moniker stuck with me, because in the 2010s it felt like we were all unlearning economics, or at least the part of economics than deals with recessions. The housing crash, the financial crisis, and the Great Recession that followed seemed to turn much of the conventional macro wisdom on its head.

Macro models before 2008 typically didn’t even include a financial sector, much less allow for the possibility that a financial crash could take down an economy (Ben Bernanke’s models were one of the very few exceptions, which is why he won the Nobel prize this year). The shape of the crisis also surprised many economists, who had expected that chronic U.S. trade deficits and budget deficits would lead to a fall in the dollar and a rise in U.S. borrowing costs; instead, when the crisis happened, money flowed into the U.S., interest rates fell, and the dollar strengthened. A number of macroeconomists also thought that quantitative easing and the zero interest rate policy (QE and ZIRP) that the Fed used to fight the crisis would cause inflation; instead, the U.S. persistently under-shot its 2% target in the decade following 2008.

This was clearly quite a lot of egg on the face of the academic macroeconomics establishment and the consensus it had settled on in the mid-2000s. For a decade, while academics tried to quickly shoehorn finance into their models and began to experiment with unorthodox ideas, the econ commentariat and much of the finance industry started looking to alternative ideas — to Post-Keynesians, sectoral balances thinking, and even occasionally to goofy stuff like MMT. It was a time of ferment and uncertainty.

But then came the 2020s, and the aftermath of the Covid shock, and things changed yet again. The commentariat has been a bit slow to notice it, but the events of the past two years have again caused us to question our assumptions about how the macroeconomy works. Except this time, it’s the heterodox “lessons” of the 2010s that are being called into question — what’s happening now looks a lot more like what orthodox macroeconomics would have predicted before 2008. That does mean the Great Recession should teach us nothing, but it’s helping to clarify what we should and shouldn’t have learned.

Here are three examples.

Market crashes don’t always crash the real economy

The biggest lesson of 2008 was that finance matters — a lot. It was obvious that the financial crisis led directly to the Great Recession. It should have been obvious before 2008 that this could happen, given the experiences of the Great Depression, Japan in 1989, and Sweden in 1990. But after 2008, you basically couldn’t find a macroeconomist willing to argue that goings-on in asset markets and the banking system don’t affect the real economy. The idea that economic recoveries are slower after financial crises became a universally accepted truism.

But that leaves the all-important question of how finance affects the real economy. There were two big financial events in 2007-8, not just one — a crash in housing prices, and a banking crisis that began with the failure of Bear Stearns and Lehman Brothers. They happened at the same time, so it was hard to separate the effect of one from the effect of the other. Which was the true “financial crisis” here?

There are some people — for example, Dean Baker — who believe that the housing bust, not the banking crisis that followed, was the main cause of the Great Recession. Because the rotation away from housing construction was far too small to cause anything like the Great Recession, the main channel would have had to have been the “wealth effect” — people feeling poorer because their houses were worth less, and consuming less because they felt poorer.

This argument relies crucially on the notion that housing works differently than stocks. We know that stocks crashed in 2000 without a major recession, and we know that stocks (and crypto!) recently crashed without yet causing a recession, so housing would have to just be different. But maybe it is! Case, Quigley, and Shiller (2005) found that drops in stock wealth are much less correlated with reduced consumption than drops in housing wealth. That could be because stocks are mostly owned by rich people, while housing forms the backbone of middle-class wealth, and the middle class is much more likely to cut back on consumption when their wealth falls.

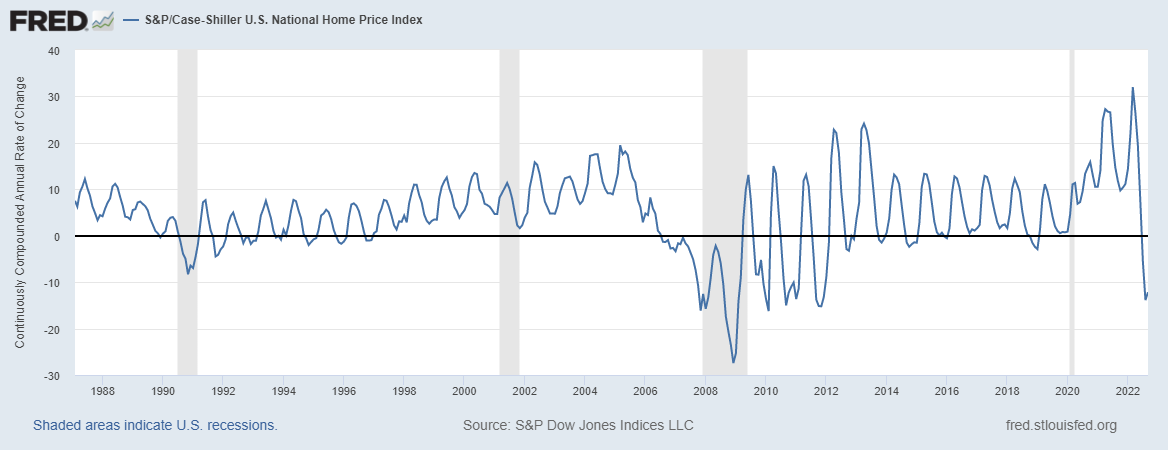

But what’s interesting is that right now, the Fed is raising rates and bringing housing prices down, and we’re nowhere near a recession yet. The fall in house prices in September 2022 was almost as steep as the fall in house prices in the months right before the Great Recession officially began in late 2007:

The data isn’t in yet, but the drop certainly continued in October, November, and December. And although many are predicting a recession in 2023, there’s still no sign of one yet.

The most plausible explanation for this is that banking crises, not just housing bubbles, are of critical importance when it comes to the connection between finance and the real economy. This is the conclusion that many in the commentariat and private industry are now reaching:

Banks are…awash in deposits, courtesy of the excess savings that Americans built up…during the pandemic…

“This housing downturn is different from the 2008 crash,” Bloomberg chief US economist Anna Wong and colleague Eliza Winger said in a note. Mortgage credit quality is higher than it was then, they wrote…[T]he mortgage market still has an effective backstop in the form of the nationalized financiers Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac.

“Maybe we shouldn’t be surprised that housing isn’t more disruptive to the financial system — because we federalized it,” said former Fed official Vincent Reinhart[.]

It’s possible that the reason housing bubbles tend to be more damaging than stock bubbles isn’t mainly because of the wealth effect — it’s because housing bubbles tend to involve a lot more debt. Most people take out mortgages to buy houses, and those mortgages often get held on banks’ balance sheets in one form or another, and banks use it as collateral to issue yet more debt. So when even a few people don’t pay back their mortgages, the banking system tends to go under. Jorda, Schularick, and Taylor (2015) have a paper in which they find that bubbles and debt are a uniquely dangerous combination, because together they tend to crash the banking system:

History shows that not all bubbles are alike. Some have enormous costs for the economy, while others blow over. We demonstrate that what makes some bubbles more dangerous than others is credit. When fueled by credit booms asset price bubbles increase financial crisis risks; upon collapse they tend to be followed by deeper recessions and slower recoveries. Credit-financed house price bubbles have emerged as a particularly dangerous phenomenon.

In other words, the 2010s taught us to be very afraid of bubbles, but now it seems like maybe the main thing we need to be afraid of, when it comes to those very severe recessions and slow recoveries, is a banking collapse. That doesn’t mean bubbles aren’t dangerous, but it suggests that we need to be especially concerned about excessive leverage and fragility in the finance industry itself.

There is such a thing as a government borrowing too much

One notable thing about the recovery from the Great Recession is that having governments borrow a lot of money turned out to be a good thing; countries that engaged in austerity generally fared poorly relative to countries that turned on the spending taps. The effectiveness of fiscal stimulus, especially in a deep recession when interest rates hit the zero lower bound, was one of the enduring and important lessons of the 2010s.

Some people worried that all that borrowing would cause interest rates to soar, but it didn’t. This caused a lot of macro critics — especially Post-Keynesians, British socialists, MMT people, etc. — to declare that the “loanable funds” model of government finance is dead.

Let’s take a fun little detour and learn what that means! The loanable funds model is a little toy model that we teach in introductory macroeconomics classes, to help undergrads understand how borrowing affects interest rates. Basically the idea is that a loan is a commodity, like apples or haircuts, and so it has a supply curve and a demand curve like any other commodity. The price of loans is just the interest rate, so the supply-and-demand graph looks like this:

As you can see, in this little toy model, when borrowers borrow more it raises the interest rate. That makes sense — if I came to you and wanted to borrow $1, you might not charge me interest, but if I came to you and wanted to borrow $1000, you might be worried I wouldn’t pay you back, and so you would probably demand some interest as compensation for that risk, and for your loss of liquidity (i.e. the fact that you have to go without that $1000 for a while).

Now, the real world doesn’t quite work like this. There are a whole bunch of different types of loans out there — government bonds, corporate bonds, bank loans, mortgages, etc. Each one has its own interest rate, and its own supply and demand curves. The loanable funds model assumes that these loans are all, in some sense, substitutes, like pencils and pens. In other words, it assumes that government borrowing is competing directly with corporate borrowing, mortgage borrowing, etc. If that’s true, then more government borrowing will raise the interest rate, not just for government bonds, but for companies, homebuyers, etc. — just like when people go buy up all the pens in the store, it’ll make pencils go up in price too.

That’s not always a good assumption. If government borrows money to spend on fiscal stimulus, and this increases demand for companies’ products, it could actually make people want to lend more to those companies, because their economic prospects are now better. Sometimes, instead of the government “crowding out” private borrowers, it crowds them in.

So the loanable funds model isn’t always useful — at least, not if we’re trying to analyze the effect of one type of borrowing on the overall interest rate environment. But some people take this a step further and assert that government borrowing doesn’t affect interest rates at all, or even lowers rates. For example, in 2019 Stephanie Kelton (the MMT guru) wrote the following in Bloomberg:

Does expansionary fiscal policy reduce interest rates? Answer: Yes. Pumping money into the economy increases bank reserves and reduces banks' bids for federal funds. Any banker will tell you this.

Well, I’m not sure if most bankers would agree with this, and I doubt many would be willing to fully embrace MMT. But the experience of Europe and the U.S. in the 2010s, and of Japan in the 1990s, certainly seemed to reduce the general worry among the econ commentariat and the finance industry that government borrowing would lead to high interest rates. After all, these rich countries borrowed and borrowed and borrowed, and their rates just went down and down. The legendary “bond vigilantes” that were supposed to swoop in and raise rates to punish excessive borrowing never showed their faces.

Then came the 2020s. Earlier this year, British Prime Minister Liz Truss released a package of tax cuts (which, I should note, the MMT people generally support), with disastrous effects. The interest rates on UK government bonds (called “gilts”) soared:

Keep in mind that these are long-term interest rates, so this wasn’t the doing of the central bank.

Why did this happen, when all that government borrowing in the 2010s never had this sort of effect? There are two likely answers here. First, the financial crisis put pressure on banks and other financial companies, forcing them to put their money in very safe and liquid assets — i.e., government bonds. Second, international investors also felt this need, and so they poured money into the safest places around — i.e., the U.S. and the EU, which hold the world’s reserve currencies.

Neither of those things were in effect for the UK in 2022. The pound isn’t a major reserve currency, and there isn’t a flight to safety or liquidity in effect right now because there isn’t a major recession in effect right now. So when the UK government declared its intention to borrow too much, people became less willing to lend it money, and rates went up.

Of course, an MMTer might respond that interest rates only went up because the Bank of England allowed it — after all, it could have bought gilts to keep rates down. But this takes us to the final 2010s macro lesson that we need to unlearn — the idea that expansionary monetary policy doesn’t cause high inflation.

Easy money is inflationary after all

Another big lesson many people took away from the 2010s was not to be very worried that easy monetary policy would lead to inflation. In 2008-13, the Fed lowered rates to zero, promised to keep them at zero, and engaged in a then-unprecedented amount of quantitative easing (i.e. having the Fed buy various long-term government bonds and private-sector bonds with money that was essentially “printed”). A lot of orthodox thinkers were quite worried about this, and wrote an open letter to then-Fed Chair Ben Bernanke in 2010 warning about inflation. It never happened.

To some, this failure of inflation to materialize meant that inflation simply wasn’t as big of a danger as we had been led to believe — that the price level mostly responds to fiscal policy rather than monetary policy, or to underlying factors like population aging, or even to special circumstances like political instability. I can’t really point you to people who strongly insisted that inflation had been banished forever, but its sudden, fierce return definitely seemed to catch everyone off guard — including the Fed, which waited about a year after the return of inflation to start hiking rates.

During Covid and its immediate aftermath, the Fed again engaged in enormous amounts of unconventional monetary easing, expanding its toolkit even compared to what it had employed after the financial crisis. Many predicted, based on the experience of the 2010s, that this would no more result in runaway inflation than it had under Bernanke. This time, though, inflation did rise — a lot. People have argued back and forth about how much demand shocks and supply shocks were responsible for the inflation, but the general consensus answer seems to be that both contributed. High demand was probably due to some combination of fiscal and monetary policy. But the fact that inflation only seems to be coming down after a series of interest rate hikes — long after fiscal stimulus mostly dried up — suggests that monetary policy did play a role.

An even starker example is provided by Turkey, which has clung to the bizarre (and MMT-endorsed) idea that low interest rates are deflationary — an idea that a few macroeconomists began to seriously entertain back during the 2010s — but which is now experiencing soaring inflation instead. Oops!

This all looks like a win for New Keynesian theory, which posits that monetary policy is the main source of changes in aggregate demand (at least, away from the zero lower bound). The simple explanation for why easy money didn’t raise inflation in the 2010s is that aggregate demand was simply depressed; QE wasn’t enough to cancel out the huge hole the financial crisis had left, even with an assist from fiscal stimulus. In 2021-22, aggregate demand bounced back very strongly from the Covid shock — with unemployment low and growth high, adding more demand via easy monetary policy was adding fuel to the fire. Note: I interviewed Paul Krugman for Bloomberg in May 2020, when many still thought Covid would lead to another long depression, and our most famous Keynesian got it exactly right:

My take is that the Covid slump is more like 1979-82 than 2007-09: it wasn’t caused by imbalances that will take years to correct. So that would suggest fast recovery once the virus is contained…[R]ight now I don’t see the case for a multiyear depression. People expecting this slump to look like the last one seem to me to be fighting the last war.

Interestingly, 2020-22 could also be seen as a win for “old monetarism”, the Milton Friedman school of thought that says that “high-powered money” — currency plus bank reserves — is the culprit when it comes to inflation. All the QE of the 2010s barely raised the M2 money supply at all, but M2 absolutely exploded in 2020 and 2021:

Friedman would probably have looked at this graph and predicted that we’d get inflation in the early 2020s but not in the 2010s. And he’d have been right.

So to sum up, the early 2020s have basically taught us to worry about asset bubbles a bit less than we did in the 2010s, and to worry about excessive government stimulus a bit more. But that doesn’t mean that everything we learned in the 2010s was bunk. Private banking systems really are fragile without the government to stabilize them. Aggregate demand definitely does matter, and the government really can affect it, with both fiscal and monetary policy. Basic Keynesian macroeconomic intuition still looks pretty good in the 2020s, just as it did in the 2010s and before. Of course that intuition is very far from settled science, but it’s still the best thing we’ve got.

This was great overview thanks.

Seems like fighting last war is always a problem especially with something so scarring as the Great Recession

In 2005, too many ingnored the money supply created by banks, private lending and didn't fully comprehend how out of hand private debt had gotten with loosened lending standards.

Then in 2020, too many didn't understand how low interest rates and expanded money could feed inflation even while private debt was tame and savings high, because low rates were into face of much different set up,

I'd add in the age demographics we're overlooked. Beyond overlerage in 2007, the other thing for U.S. that had hurting us more in 2010s was just as housing debt got carried away, the Gen X population trough came of working age, househokd formation age, so big over leverage and over supply right into face of less buyers, really really crahed housing+.

Then in 2020 we had huge population of Millennials hit peak home buying ages, while supply was low and interest rates low and most people had more savings and also huge shift in type of demand towards SFHs (work from home needing extra space etc), and wham, housing went out of control.

So Fed low interest rates weren't at all counter cycle this huge part of economy in 2020. Turns out housing didn't need help of low rates in 2020 like it did in 2010, even with pandemic and really,

partly because pandemic.

Other big lesson of what missed this time is how important supply is to taming inflation. In last war in 2010, that was not a thing because gas was in good supply with fracking boom in U S. and housing had been overbuilt due to overlerage.

This time, in 2020, lack of supply in housing building because of bad policies and because of pandemic supply disruptions worked against free easy money

Discussing today's economic events with no mention of the war in Ukraine, Russian sanctions, zero-covid in China, the effects of Covid on workforce participation and the effects of climate change on global agriculture seems wrong. Macro is navel gazing and missing the fact that the economy exists in the real world?