Trudeau was a poor steward of Canada's economy

No one knows what ails Canada, but Trudeau didn't try very hard to fix it.

Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau just resigned. The immediate cause of his resignation is obvious — his party is doing terribly in the polls, and there’s an election coming up this year:

Canada’s Liberals are probably going to suffer the same fate as incumbent parties all over the developed world, but their best chance to avoid it was probably to dump Trudeau. So they forced him out.

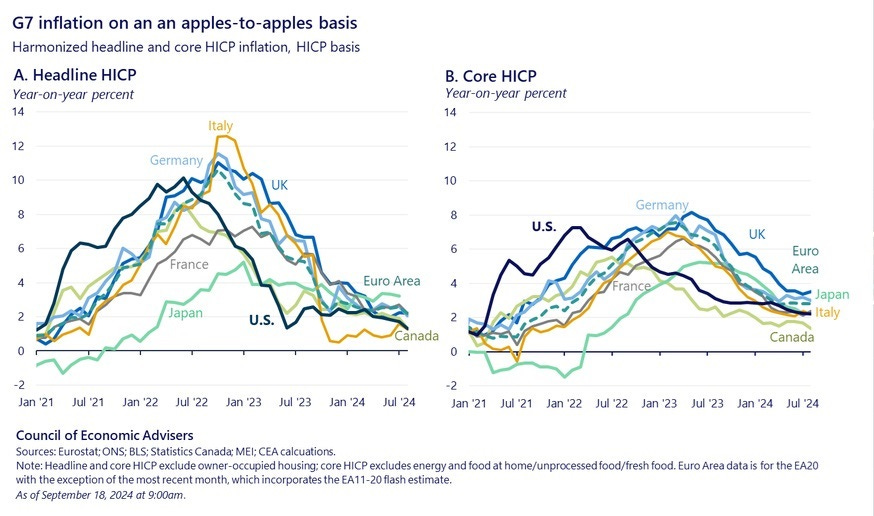

The deeper causes of Trudeau’s unpopularity are less clear. There’s the inflation factor, of course, which has produced rumblings of dissent all over the globe. Though it’s notable that Canada’s inflation peaked at a lower value than America’s, and came down just as quickly:

Trudeau also suffered from a number of personal scandals. He suffered a major corruption scandal in 2019, and was found to have appeared in blackface a number of times in his youth.

Then there are sociocultural issues. In recent years, Canadians have grown less supportive of the country’s high immigration rate:

A September poll by Environics Institute, which has tracked Canadians' attitudes towards immigration since 1977, revealed that for the first time in a quarter century, a majority now say there is too much immigration…The institute said these shifting attitudes are primarily driven by concerns over limited housing. But the economy, over-population, and how the immigration system is being managed were also cited as big factors…In an October newsletter, Abacus Data pollster David Coletto said that the idea that "consensus around immigration is cracking is an understatement".

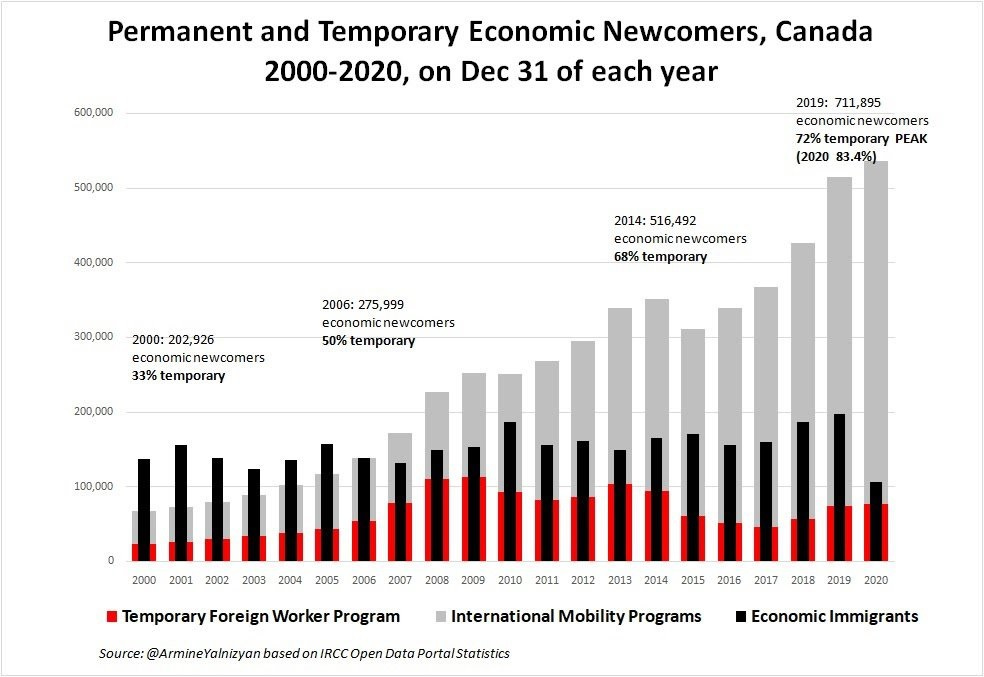

Trudeau and the Liberals have presided over a shift in the type of immigrants coming to Canada. Traditionally, the country focused on high-skilled immigration; nine years ago, when Trudeau had just come to power, I called it the world’s best immigration system. But by the time I wrote that, the country’s leaders had already opened the country up to far more lower-skilled temporary workers, especially under the International Mobility Program. Trudeau continued this trend, and by the time the pandemic rolled around, most foreigners coming into Canada were of the temporary variety:

Trudeau also vastly increased the number of foreign students, many of whom started claiming asylum after entering the country on student visas. Even the traditionally tolerant, welcoming Canadians may have seen the opening up of true mass migration as a bridge too far. Trudeau’s deemphasis on assimilation, and his declaration that Canada has “no core identity”, probably exacerbated fears of cultural change. The flood of temporary workers has contributed to rising rents, despite a modest boom in homebuilding.

Nor is immigration Canada’s only cultural sore point. There’s the country’s vastly expanded use of euthanasia, with all of the attendant moral hazard. There’s a big fight over trans issues. In general, Canada is suffering a similar backlash against “wokeness” to what is occurring in the U.S. and the UK, with perhaps a slightly greater lag.

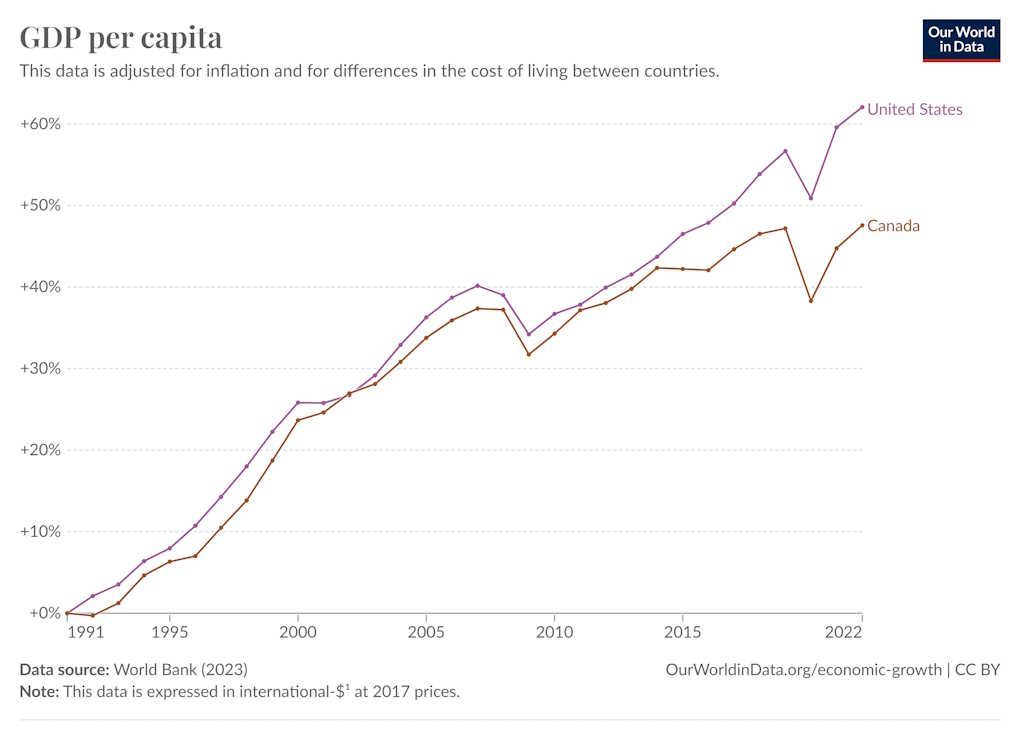

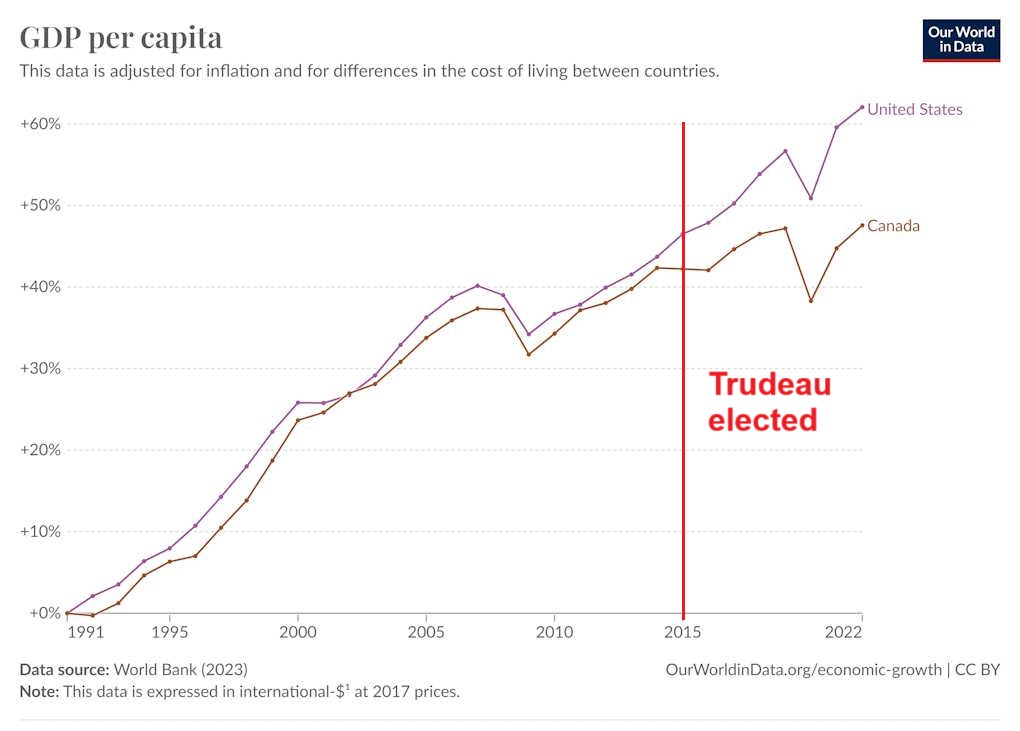

But on top of all of that, there’s Canada’s economic stagnation. As you can see from the chart at the top of this post, Canada’s income levels grew in tandem with America’s from 1991 to 2014. But then starting in 2015 — the year Trudeau was elected — the two diverged. Let’s post that chart again, with a marker for Trudeau’s term:

This stagnation is unlikely to have begun with Trudeau, since the timing is off. Trudeau only took power at the end of 2015, and his policies are unlikely to have had a major effect on Canada’s economy until years later. Instead, the primary culprit behind Canada’s initial stagnation in the mid-2010s is pretty easy to see: it’s oil prices.

Canada isn’t quite a petrostate, but ever since the development of the tar sands, it has been moving in that direction. Oil and related products are Canada’s biggest export category:

Overall, the industry is responsible for over 6% of Canada’s GDP. But that understates oil’s importance, because exports generate local multipliers — the money that comes in from exports gets spread around domestically, generating yet more economic activity. So oil is quite important for Canada.

And in 2015, oil prices took a big tumble, from which they never recovered:

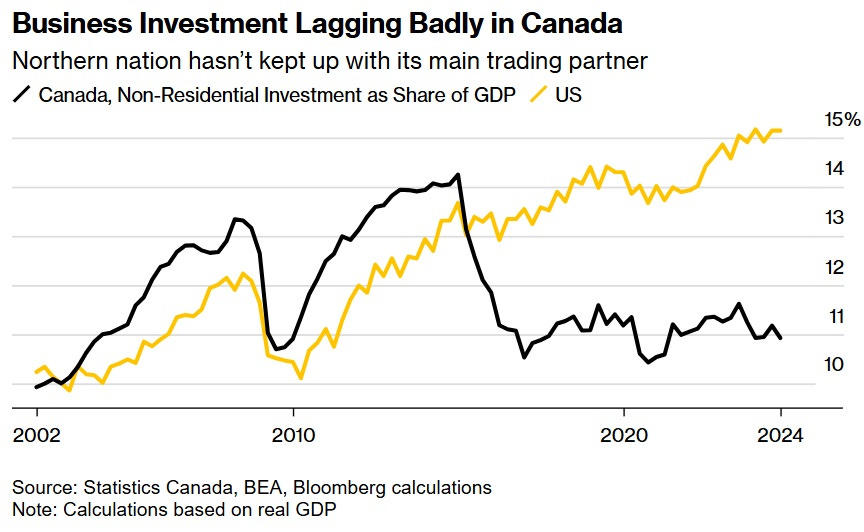

When the price for your top export gets suddenly cut in half, you will suffer economically. Perhaps Canada didn’t have to suffer quite as much as it did, but this was never going to be a fun or easy process. The oil price collapse is one major reason that Canadian business investment plunged in 2015:

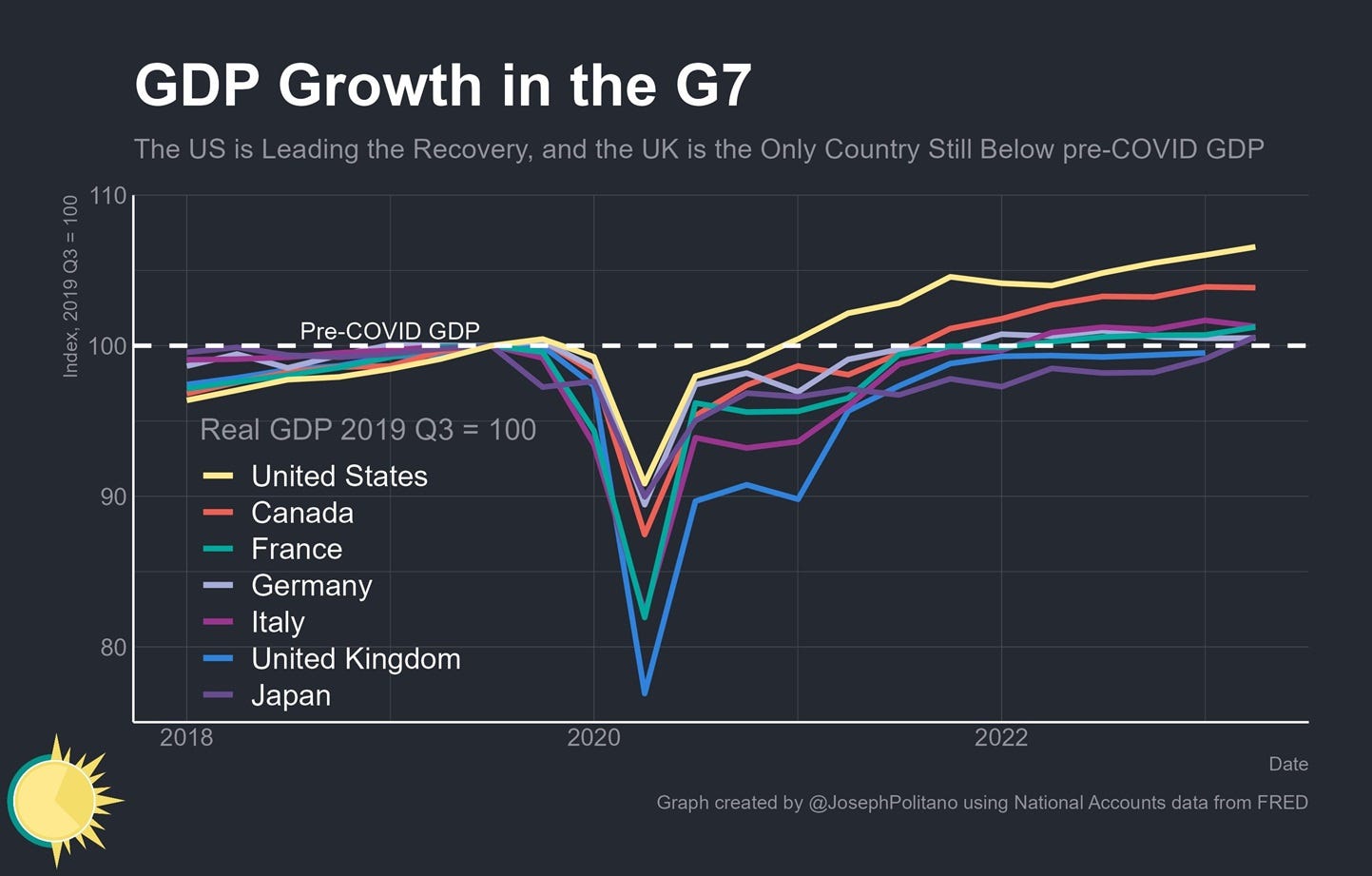

But it’s Canada’s weak performance in the years since the pandemic that really sets it apart. On the surface, things might look like they’ve gone OK — Canada’s total GDP rose by a healthy amount in 2021-2023, lagging only a little behind America:

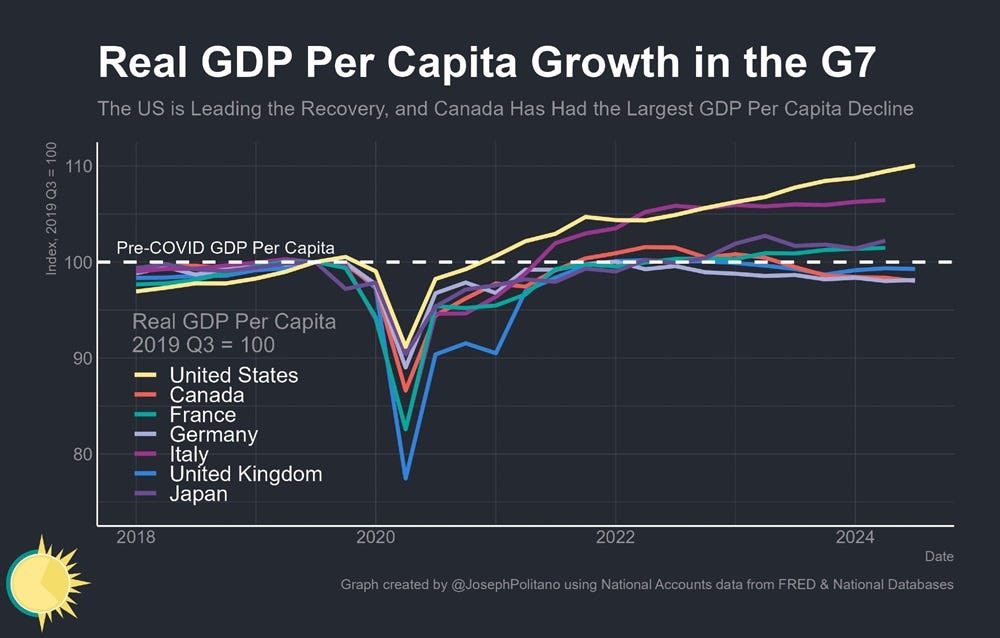

But this is an illusion, created by Canada’s huge admission of temporary migrants during those years. In per capita terms, the country’s living standards underperformed the entire rest of the G7, even as America’s soared:

In fact, Canadian opposition leader (and likely next prime minister) Pierre Poilievre posted this chart — with the source and watermark removed — as evidence of Trudeau’s failure.1

Oil prices aren’t a good explanation for this post-pandemic stagnation, since they’ve risen significantly since 2019. Nor did oil production collapse under Trudeau — despite the investment drought, Canadian crude production hit an all-time high in 2022 and again in 2023, as did crude oil exports. But Canadian business investment has stayed low, and living standards have flatlined and begun to fall, nonetheless.

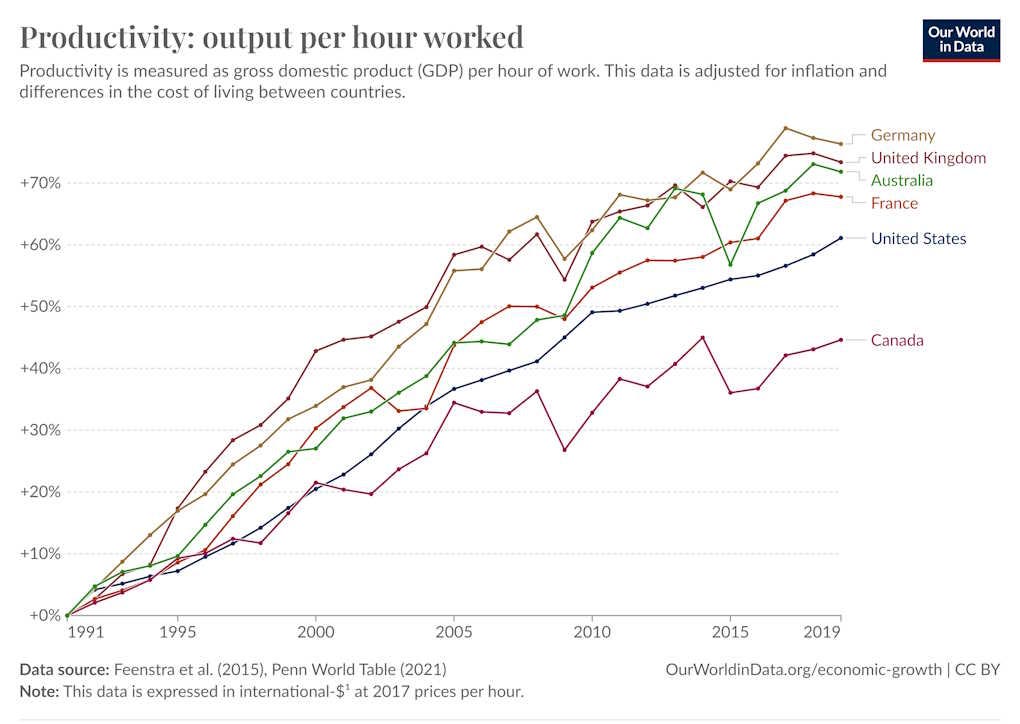

What’s going on? Some of the negative trends in Canada’s economy are long-term things. For example, Canada’s productivity growth has been strangely slow for decades:

(Actually the slowdown began in the 1980s, but this nice-looking cross-country comparison chart only begins in 1990.)

This long-term productivity stagnation has been masked by the steady rise of oil. In fact, despite the price crash and the accompanying investment drought, Canada has become much more of a petrostate since Trudeau took office — crude oil was only 12.5% of Canada’s goods exports in 2015, compared to 20.9% in 2022.

It’s Canada’s non-oil business sector that has failed to raise productivity since the 1980s, and which has done even more poorly under Trudeau.

RBC, the biggest Canadian bank, has a good report on some of the long-term regulatory and tax issues that hold back Canadian productivity and business investment. Here are a few excerpts:

Some of the causes of Canada’s long-term slowdown in economic growth are well-known and clear. Let‘s start with an inefficient regulatory and administrative approval system at all levels of government, which has unintentionally increased internal barriers to trade and growth. Infrastructure chokepoints and red tape further make international trade more difficult than it should be. Those have contributed to lower Canadian business investment, and with that, an overweight of capital going to buildings and construction, which, while valuable to the economy, don’t do as much for growth as machinery and intellectual property do…

A patchwork of regulatory and administrative rules across different municipalities and provinces is complicated and unintentionally restricts trade within Canada…The International Monetary Fund has estimated that internal trade barriers (for example, regulatory differences across regions, paperwork requirements for businesses in multiple jurisdictions, and certification differences that limit labour mobility) cost the equivalent of a 20% average tariff between provinces…

In 2020, Canada ranked 188th out of 208 economies tracked by the World Bank on the number of days businesses spent dealing with construction permits for new projects. That is three times longer than time spent in the U.S…

Red tape also makes it more expensive for companies to trade across international borders. Actual tariff rates on international trade in Canada are low, but Canada ranks poorly (51st globally) in the ease of trading across borders in large part due to high administrative costs associated with importing and exporting.

The report also provides a sobering reminder that human capital isn’t the only thing you need for growth. Not only has Canada taken in tons of skilled immigrants over the years, it has spent a huge and increasing amount on educating its own populace, and has sent more and more of its people to college, only to see productivity stagnate.

But what has Trudeau himself done to make things worse? A 2023 report by the Fraser Institute is frustratingly vague, citing anti-business attitudes and a reliance on government debt and fiscal stimulus. But the the latter should actually boost growth in the short term — after all, the U.S. did far more deficit spending than Canada during and after the pandemic, and it has enjoyed much faster growth.

And the effects of anti-business attitudes are hard to quantify. Tax policies are something you can measure, but these were ambiguous — Canadian corporate taxes actually fell under Trudeau, but capital gains taxes went up2 and Trudeau created a new carbon tax. As for regulatory burdens, these are undoubtedly important, but no one really knows how to estimate them. Is it possible that Trudeau’s general leftishness created a climate of uncertainty for Canadian businesses that held them back from investing? Sure. But it’s hard to tell whether that was really a factor behind their decisions, or just something some of them said to reporters.

The fact is, no one seems to really know what’s behind Canada’s low productivity growth. Observers agree that low rates of corporate investment, including investment in R&D, are the problem, but no one seems to have a good explanation for why companies aren’t investing. And no one seems to know whether Canada’s especially bad performance since the pandemic is just an exacerbation of the existing negative trends, or whether some new problem has cropped up in addition. The most careful analyses, like the one by RBC and a 2023 paper by Rosell et al. of Finance Canada, point their fingers at a variety of long-term factors. Whether Trudeau’s administration exacerbated any of those factors in a meaningful way remains a mystery.

What seems pretty clear, though, is that Trudeau didn’t try very hard to fix any of Canada’s long-term problems. Even as the problems of low investment, low innovation, and low productivity went from bad to worse, and even as lower oil prices meant that petroleum exports could no longer be a band-aid on Canada’s deeper issues, Trudeau’s administration failed to mount a serious effort to get companies to invest and innovate more, or even to investigate the root causes of the country’s stagnation. It’s not clear whether Trudeau could have fixed what ails Canada, but he didn’t even seem to realize something was amiss.

Instead, he seemed to believe the commentators who declared that total GDP growth was all that matters, bulking up his economy on the cheap carbs of mass low-skilled immigration without producing any underlying strength. Trudeau may not have actively sabotaged the Canadian economy, but he certainly didn’t do much to turn the ship around. Let’s hope Poilievre can be a bit more proactive.

Failing to credit Joey Politano for the chart was an act of rudeness rare for a Canadian. Speaking on behalf of Americans, we vow to retaliate by habitually mispronouncing Poilievre’s name as either “Polliver”, “Poiliver”, or possibly even “Pollivee”.

Capital gains taxes technically don’t go up until 2025, but businesses tend to see higher taxes coming well in advance, and make decisions accordingly.

Don't use the Fraser institute. They are total hacks.

I remember one time there was a startling statistic. "40,000 Canadians had fled Canada to get better healthcare" The purpose was clear. They were trying discredit Canada's health system in the eyes of Americans.

This was in the Blaze, essentially an American right wing site.

I tracked the source and it quoted something by the Fraser institute. I looked at that and the Fraser institute said that this was based on their annual survey of Canadian doctors.

Digging into that survey, I found the question. It was "What percentage of your patients have received non emergency care outside of Canada last year?"" The answers from their survey was "about 1%".

Now this didn't ask why they received the care. Perhaps they got food poisoning on an Italian vacation. But that didn't stop the Fraser institute, they had a mission and that mission is making Americans believe that Canadian healthcare is awful. So the Fraser institute multiplied out that 1% by all Canadian patients and wrote a report where 40,000 Canadians are "fleeing" the dire state of Canada's health care.

It was total hackery.

The bit quoted in this piece where the the Fraser institute blames leftism without saying how exactly is par for the course.

For what it's worth, I think Canada is suffering from a variation of the issues other medium-sized developed countries are having. No developed country with a comparable population to Canada is doing amazingly economically right now. I think this is because once you get to this tens of millions size, you start to become so big that you find it harder to occupy small economic niches (like Ireland) and to find political consensus (like Singapore).

But you also lack the large internal markets and investment pools of the biggest countries, like China or the US. One manifestation of Canada's economic problems is the presence of oligopolies: airline and supermarket duopolies, a similar lack of competition in banking and telecoms, and so on. This is obviously related to the internal market issue: how many more airlines and banks could you support in a country with just over 40m people? The EU managed to partially overcome this problem by creating a large single market, but it is still badly integrated for capital markets and services.

These issues are then compounded in Canada by a number of factors, including:

- Its complex and byzantine federal government structure

- The country's sheer size and lack of good infrastructure links across all of it

- A larger, richer neighbour that Canada has a close relationship with but is also frightened of

- Over-dependence on commodities exports

- A (mostly) Anglo aversion to building housing and infrastructure, like the US, UK, and Australia.