Trapped in the hell of social comparison

A hypothesis about why Americans are unhappy with their economy.

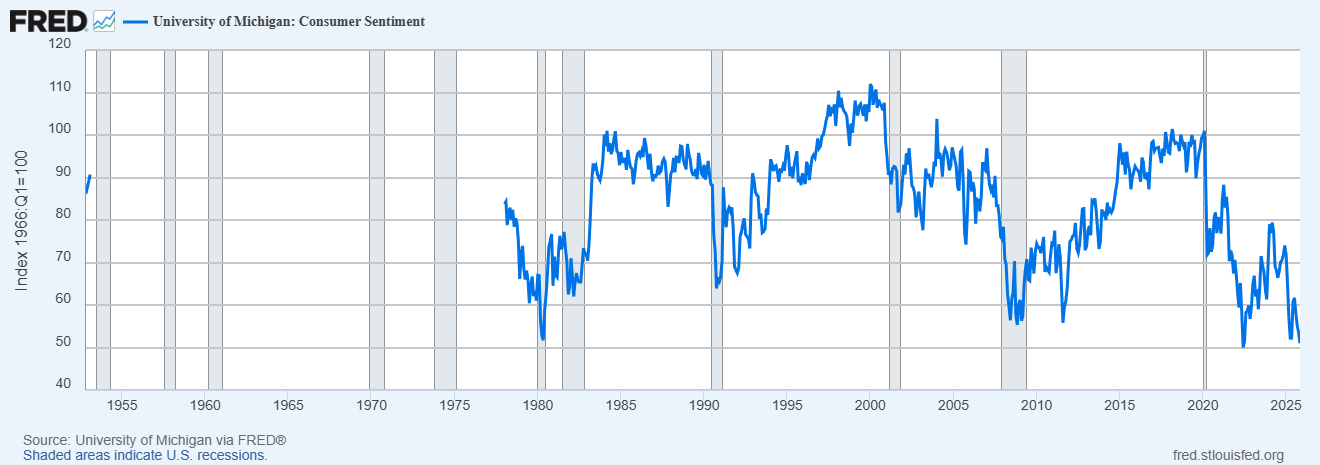

Interest rates have begun to come down. Inflation has mostly subsided, and the real economy is still doing decently well despite Trump’s tariffs. So why are American consumers more pessimistic than they were during the depths of the Great Recession or the inflation of the late 1970s?

It’s possible to spin all sorts of ad hoc hypotheses about why consumer sentiment has diverged from its traditional determinants. Perhaps Americans are upset about social issues and politics, and expressing this as dissatisfaction about the economy. Perhaps they’re mad that Trump seems to be trying to hurt the economy. Perhaps they’re scared that AI will take their jobs. And so on.

Here’s another hypothesis: Maybe Americans are down in the dumps because their perception of the “good life” is being warped by TikTok and Instagram.

I’ve been reading for many years about how social media would make Americans unhappier by prompting them to engage in more frequent social comparisons. In the 2010s, as happiness plummeted among young people, the standard story was that Facebook and Instagram were shoving our friends’ happiest moments in our faces — their smiling babies, their beautiful weddings, their exciting vacations — and instilling a sense of envy and inadequacy.

In fact, plenty of careful research found that using Facebook and Instagram made people at least temporarily unhappier, and there’s some evidence that social comparisons were the reason. Here’s Appel et al. (2016), reviewing the literature up to that point:

Cross-sectional evidence demonstrates a positive correlation between the amount of Facebook use and the frequency of social comparisons on Facebook…A similar pattern emerges for the impression of being inferior…Some of these studies…have documented an association between social comparison or envy and negative affective outcomes…

Causal relationships between Facebook use, social comparison, envy, and depression have also been established experimentally. For example, in a study about women's body image…women instructed to spend ten minutes looking at their Facebook page rated their mood lower than those looking at control websites. Furthermore, participants in the Facebook condition who had a strong tendency to compare their attractiveness to others were less satisfied with their physical appearance…

In summary, available evidence is largely consistent with the notion that Facebook use encourages unfavorable social comparisons and envy, which may in turn lead to depressed mood.

Note that during the 2010s, consumer confidence was high. Even if people were comparing their babies and vacations and boyfriends, this was not yet causing them to seethe with dissatisfaction over their material lifestyles. But social media today is very different than social media in the 2010s. It’s a lot more like television — young people nowadays spend very little time viewing content posted by their friends. Instead, they’re watching an algorithmic feed of strangers.

A lot of those strangers are “influencers” — people who either make a living or gain fame and popularity by posting about their lifestyles. And while some of those lifestyles might be humble and hardscrabble, in general they tend to be rich and leisurely.

When I asked a social media-obsessed Millennial I know to give me an example of a rich influencer, she immediately mentioned Rebecca Ma, better known by her online nickname Becca Bloom. Here’s Becca’s spectacular wedding:

And here’s a video of her and her husband letting Microsoft Copilot decide where to fly their private jet:

Most of Becca’s Instagram account is pictures of her taking trips to gorgeous, scenic locations and showing off fancy clothes and other possessions. Another example I heard was Alix Earle, whose posts mix dance performances with exotic vacations.

To be very clear, I am not criticizing, decrying, or denouncing social media influencers like this. Becca Bloom looks like a nice person that I might go to a party with — and there’s absolutely nothing wrong with having a beautiful wedding, hanging out on the beach, or visiting cities in Europe. But how many Americans can afford to live that lifestyle? Becca Bloom comes from a super-rich Hong Kong family, a successful entrepreneur who sold her technology company in 2018. She’s top 0.01% for sure.

There were rich people like that in 1920, or 1960, or 1990. But you almost never saw them. Maybe you could read about them in People magazine or watch a TV show about them. But most people simply didn’t have contact with the super-rich. Now, thanks to social media, they do. And even if people don’t go hunting for “RichTok” videos, the algorithmic feed may occasionally throw some into their field of view. On a day-to-day basis, we are more aware of the Becca Blooms of this world than we were thirty years ago, or probably even ten years ago.

But even more subtle might be the influencers who are merely upper class rather than spectacularly rich. Since I don’t follow any lifestyle influencers, I asked AI for a few examples, and here are a few it mentioned:

These people aren’t living the lifestyle of a Becca Bloom, yet most of what you’re seeing in these photos and videos is economically out of reach for the average American. Most Americans can’t afford a big fancy house like Merritt Beck’s or Carly Riordan’s, a gorgeous European vacation like Jacey Duprie’s, or fancy dinner parties like Kate Arends’.

And yet these are not obviously rich people, either — they’re more like the 5% or the 1% than the 0.01%. Their lifestyles are out of reach for most, but not obviously out of reach. Looking at any of these videos, you might unconsciously wonder “Why don’t I live like that?”.

Americans were always shown examples of aspirational lifestyles. The house in the Brady Bunch and the apartments in Friends were more spacious and well-appointed than the average American residences at the time, and you’d see the same exaggerations in advertisements. Yet on some level, Americans might have realized that that was fiction; when you see a lifestyle influencer on TikTok or Instagram, you feel like you’re seeing simple, bare-bones reality. (And often, though not always, you are.)

I was talking to my friend David Marx about this, and he pointed out that the rise of social media influencers has scrambled our social reference points.

Humans have always compared ourselves to others, but before social media, we compared ourselves to the people around us — our coworkers, friends, family, and neighbors. “Keeping up with the Joneses” has always been a well-known concept, and many economists have documented the effect in real life. For example, here’s Card et al. (2012) on salary comparisons:

We study the effect of disclosing information on peers' salaries on workers' job satisfaction…Workers with salaries below the median for their pay unit and occupation report lower pay and job satisfaction and a significant increase in the likelihood of looking for a new job. Above-median earners are unaffected. Differences in pay rank matter more than differences in pay levels.

And here’s Luttmer (2005), finding that having richer neighbors makes you less happy:

This paper investigates whether individuals feel worse off when others around them earn more. In other words, do people care about relative position, and does “lagging behind the Joneses” diminish well-being?…I find that, controlling for an individual's own income, higher earnings of neighbors are associated with lower levels of self-reported happiness…There is suggestive evidence that the negative effect of increases in neighbors' earnings on own well-being is most likely caused by interpersonal preferences, that is, people having utility functions that depend on relative consumption in addition to absolute consumption.

But comparing yourself to neighbors, coworkers, family, and friends was different than comparing yourself to social media influencers, in at least a couple of important ways.

First, all of those classic reference points tended to be people who were roughly similar to us in income — maybe a little higher, maybe a little lower, but usually not hugely different, and certainly not Becca Bloom types. Housing markets, job markets, and all kinds of other forces tend to sort us into relatively homogeneous social classes. The rich and the poor were always fairly removed from the middle class, both geographically and socially.

But perhaps even more importantly — and this was a point that David Marx especially emphasized — we were able to explain the differences we saw. In 1995, if you knew a rich guy who owned a car dealership, you knew how he made his money. If you envied his big house and his nice car, you could tell yourself that he had those things because of hard work, natural ability, willingness to accept risk, and maybe luck. The “luck” part would rankle, but it was only one factor among many. And you knew that if you, too, opened a successful car dealership, you could have all of those same things.

But now consider looking at an upper-class social media influencer like the ones I cited above. It’s not immediately obvious what they do for work, or how they could afford all those nice things. Some of them have jobs or run businesses, but you don’t know what those are. Some might have inherited their wealth. Some of them make money only by showing off their lifestyles on social media!

Not only can you not explain the wealth you’re seeing on social media, but you probably don’t even think about explaining it. It’s just floating there, delocalized, in front of you — something that other people have that you don’t. Perhaps you make it your reference point by default, unconsciously and automatically, as if you’re looking at your sister’s house or your neighbor’s car.

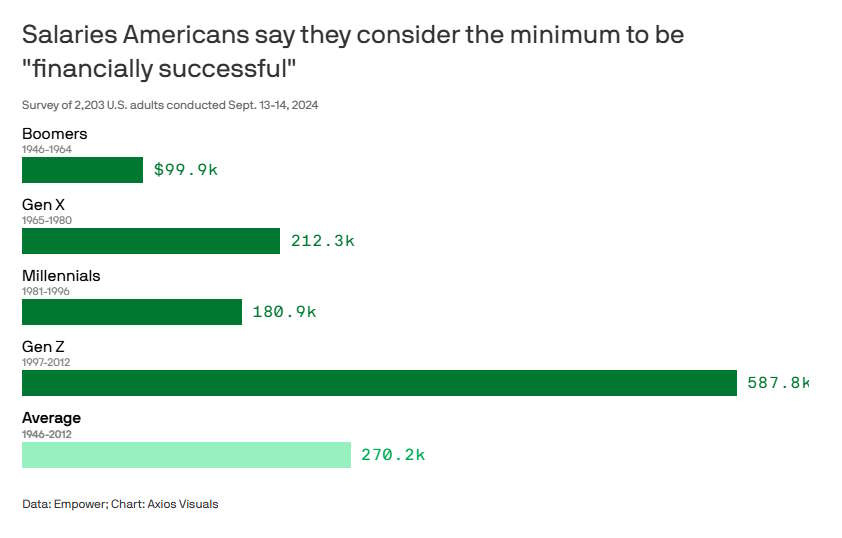

I’m hardly the first person to think of this idea. Other writers are starting to use terms like “money dysmorphia” and “financial dysmorphia” to describe the vague sense of inadequacy that comes from being bombarded with deracinated free-floating images of wealth and comfort. A lot of people have taken note of a recent survey by the financial services company Empower, in which Gen Z reported a much higher threshold for considering themselves financially successful:

$588,000 is an absurd requirement for financial success. It’s in the top 1% of individual incomes. It’s thirteen times the median personal income in the United States, and more than five times the median family income.

Now, with surveys like this, you always have to worry about wording. It’s possible that terminology has changed, so that the phrase “financially successful” connotes “rich” to Gen Z, while it means “upper middle class” to older generations. But it’s also possible that Gen Z folks really do think they’re losers if they don’t make $588k. And this impression might come from TikTok and Instagram — many of the influencers I listed above look like they probably make in the ballpark of that amount.1

If social media comparison is really making middle-class Americans feel like financial losers, what do we do about it? It’s physically impossible to give every American an income anywhere near $588k, at least in the near future. We can redistribute more wealth and income, but taxing the top 5% down to a humble middle-class standard of living just to make social media consumers less grumpy is probably a political non-starter. We could have a communist revolution, but history shows that this is a bad idea.

And if social comparisons are getting Americans down, the Abundance agenda is likely to be less powerful than we might hope. Economic theory and common sense both tell us that even if people’s satisfaction depends on other people’s wealth, getting richer still makes them happier. But social comparisons can put a lid on how happy we can feasibly make people.

So neither redistribution nor growth nor any combination of the two will give regular folks the kind of lifestyle they see on TikTok and Instagram. Hopefully over time people will learn that influencer lifestyles aren’t a good barometer of reality — that fancy Europe trips and cavernous mansions are as rare now as having a giant apartment in Manhattan was in the 1990s.

In the meantime, I suppose we can strive to make society more equal in other ways, so that lifestyle differences matter less. We can provide more public goods — nice parks, walkable streets, good transit, beautiful free public beaches. We might even be able to cultivate a culture like Japan’s, where most rich people are embarrassed to display too much wealth in public. And we can continue prodding young people to watch less TikTok and Instagram.

All of those solutions are, of course, predicated on social comparison actually being a major reason behind low economic satisfaction. It might not be. But it’s an important hypothesis we should consider.

There are some more modest middle-class influencers out there, like Emily Mariko, but the upper class seems to dominate — probably because people like looking at fancy expensive stuff.

Not sure how to test this or prove it, but I think the precariousness is the biggest issue. It's almost like people emotionally "feel" their wealth as including their anticipated future cash flows - and they know those future flows are very uncertain.

I've been wondering if this is why the old Boomer model of a steady job with a modest salary made people happy. You might not get a Ferrari, but you also saw financial ruin as unlikely (barring reckless choices - gamblers etc).

Curious if the professional economists have ever investigated this.

It's an interesting hypothesis, but I'm not sure how much it actually explains the data. Most polls find that people are happy about their own finances, while they are very pessimistic about their country's economy (see https://hannahritchie.substack.com/p/many-people-are-individually-optimistic for an example, which shows that this trend goes beyond economics). If your hypothesis was true, then people would feel negatively about their own finances instead.

Social media may be responsible for the negative economic sentiment, but most likely because its algorithms have been optimised to push negative stories into us, as we are more likely to engage with them.