Time for a Diplomatic Revolution

Cold War 2 is here, and the U.S. needs all the allies we can get.

Note: I’m taking a brief break from posting about economics to offer some ideas on geopolitics and international relations. I’m not any kind of an expert on these things, so as always, take what I have to say with a grain of salt. But remember that lots of other people confidently writing about these subjects make no such disclaimers when they offer their opinions.

Diplomatic revolutions are amazing things. In some ways, they’re the pivot of history. It takes decades or even centuries for nations to rise and decline, but coalition formation can change the global balance of power in an afternoon. In 1756, Prussia and Britain went from enemies to allies, which probably helped set the stage for Germany’s rise. In 1891-1894, France and Russia created an alliance to balance Germany, which ultimately resulted in World War 1.

Nowhere did shifting alliances make more of a difference than in the middle of World War 2. In late 1940, Nazi Germany had conquered France and was allied with Japan, while the USSR had helped Hitler devour Poland. The U.S. was neutral, still hobbled by isolationism. It looked as if totalitarian powers would dominate the globe. But a year later, when Hitler turned on Stalin and Stalin allied with the U.S., the tables were entirely turned — the Allies now had a coalition that could beat the fascist powers.

In the Cold War, too, alliances played a role. When the USSR and China were communist allies during the Korean War, it was all the U.S. could do to hold them at bay; after the Sino-Soviet Split, the USSR had to worry about attack from China. The U.S. was able to exploit this by arranging a de facto alliance with China against the Soviets in the 1970s and 1980s. The Soviets probably would have lost the Cold War anyway, but the U.S.-China rapprochement probably hastened the end.

Now we find ourselves at another dangerous, potentially pivotal moment in history. Three weeks ago, it seemed as if a partnership between a newly ascendant China and a revitalized Russia might dominate the globe, bringing authoritarian values back into preeminence. The U.S.’ NATO allies seemed sleepy and irresolute, while India — the next great power on the horizon — still maintained close ties with Russia. When Putin sent tanks rolling into Ukraine without any provocation, it looked as if the authoritarian coalition’s moment had finally arrived.

Then two remarkable things happened. First, the Ukrainians resisted the invasion with a ferocity and skill that exposed the deep weaknesses in Putin’s vaunted military machine, and reminded the world that people will fight to resist totalitarian tyranny. Second, Europe suddenly roused itself from its post-Cold War torpor, imposing fierce sanctions that threaten to cripple Russia’s economy for decades, furnishing the Ukrainians with all the anti-tank weapons they can carry, pledging to boost defense spending back to late Cold War levels, and uniting around the NATO alliance.

This changes the global strategic situation overnight. Suddenly, the U.S. has a new and powerful ally in the form of a reunited Europe, while China’s most important ally turned out to have feet of clay. The war is not yet over, but things are looking much brighter for the democratic powers.

It’s not enough, though. To meet the new authoritarian challenge, the U.S. and its existing allies will have to bring more partners into the fold. A 21st century diplomatic revolution is necessary in order to create a coalition that has the power both to stabilize international relations and safeguard the human rights that have gradually but steadily made the world a better place to live.

It starts with India.

Ally with India

India is home to a fifth of humanity — the only country that can match China’s vast size. It’s also the third-largest economy when measured at purchasing power parity:

In recent years, the U.S. and India have been drawing steadily closer, cooperating more both militarily and economically. India is now part of the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue, a sort of “alliance lite” that also includes the U.S., Japan, and Australia, with Vietnam, South Korea, and New Zealand mooted as possible additional members. U.S. arms sales to India have increased dramatically in recent years, and total trade between the two countries has grown steadily. India also has a deepening economic and security relationship with Japan.

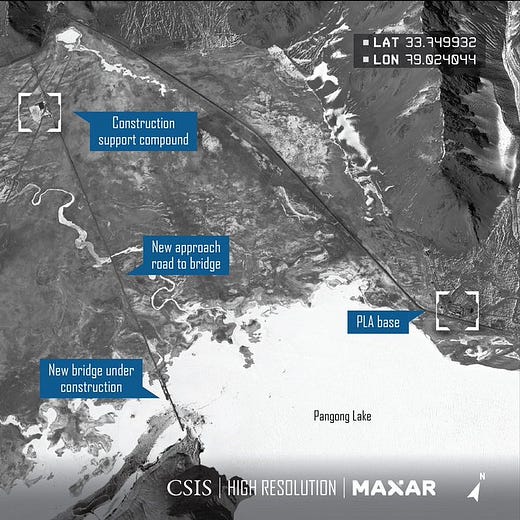

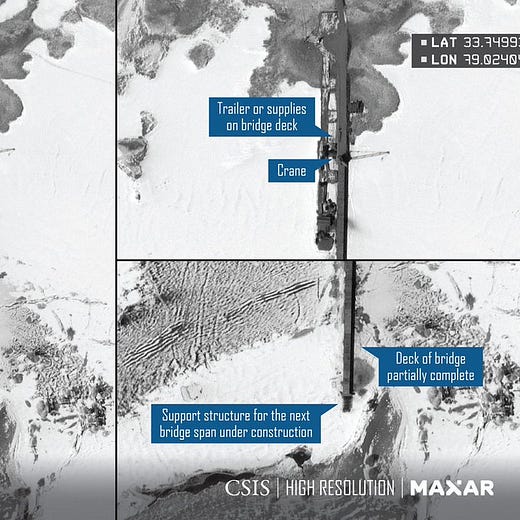

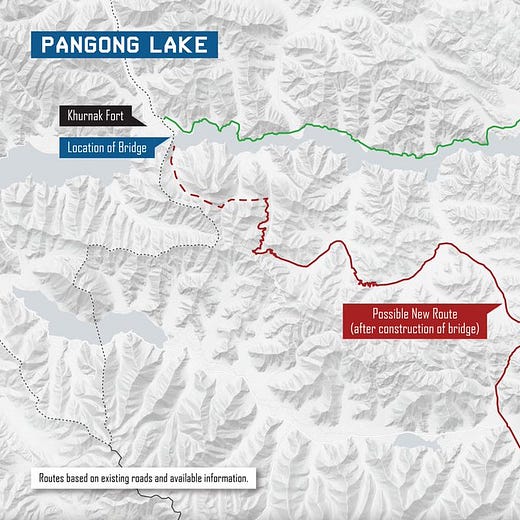

The reason for this is obvious: China. China and India have avoided outright enmity, but they are definitely rivals for influence in South and Southeast Asia. The two have a territorial dispute that sometimes flares up into bloody combat, such as a skirmish that killed dozens in 2020. China continues to militarize the disputed border:

So of course India is doing the smart thing and drawing closer to the U.S. and Japan, China’s other rivals in the region.

But India has also maintained a close quasi-alliance with Russia. This partnership is a legacy of the Cold War, when the USSR supported the officially non-aligned India in its conflicts with both China and Pakistan. To this day, despite increased arms purchases from the U.S., a large percentage of India’s military equipment comes from Russia:

A recent paper by Lalwani, O’Donnell, Sagerstrom, & Vasudeva explains the relationship in detail. The partnership is why India, like China, abstained from the UN resolution condemning Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, as well as other similar votes.

But the Ukraine invasion is causing Indian leaders to rapidly reevaluate the wisdom of relying on Russia. Not just because Russia is becoming an international pariah for its brutal, unprovoked assault, but because Russia’s poor performance in the war has shown that it’s less valuable of an ally than the Indians had been led to believe. Even Russia’s highest-technology weapons may only excel in limited dimensions, as evidenced by the photos of top-of-the-line Russian fighter-bombers using off-the-shelf commercial GPS systems clamped to their dashboards.

The problem, as Sameer Lalwani explains in an excellent Twitter thread, is that India has so many Russian weapons systems — which it relies on Russian expertise and assistance to maintain — that it can’t simply drop Russia like a hot potato. It might eventually replace Russian weapons with American ones, but this shift would take time and leave India potentially vulnerable to China and Pakistan in the meantime.

Still, at this point India may simply not have a choice. In addition to Russian military weakness, economic collapse, and moral isolation, Russia is now going to be forced to become an economic vassal of China as a result of the sanctions regime. That means that by continuing to partner with Russia, India will be making its military indirectly dependent on the country that represents India’s biggest threat. Not a good place to be.

So the U.S. needs to step in and free India from this dilemma with the offer of a much deeper partnership. U.S.-allied East European countries like Poland and even Ukraine may be able to service much of the Russian and Russian-derived tech India now uses. And the U.S. can and should attempt to quickly replace as much of India’s tech as it can.

This will require selling arms to India at steeply discounted prices — one other reason India buys weapons from Russia is that they’re cheap, and India is still a fairly low-income country. The U.S. will have to forego some profits in order to get India the tech it needs to stand up to China without Russian help.

There are several other obstacles to a close U.S.-India partnership. One is a historical suspicion dating back from the days of the Cold War. During the Cold War, the U.S. supported India’s arch-enemy Pakistan, even looking the other way when Pakistan committed genocide in Bangladesh in 1971. Even after the Cold War ended, the U.S. temporarily opposed India deploying nuclear weapons, even though Pakistan had gone nuclear with Chinese help. Only during the administration of George W. Bush did the U.S. stop trying to hold India back from the ranks of the nuclear-capable great powers.

Indians have been laudably quick to get over those old scars — in 2014, 56% of Indians had a favorable impression of the U.S., with only 15% unfavorable. But at the same time, a majority of Indians felt that their country didn’t receive enough respect on the international stage:

The fact that most Americans don’t even know about their country’s support for India’s enemies during the Cold War speaks to this lack of respect. For many decades, the U.S. simply didn’t view India as a great power worth taking seriously. Now that it’s clear that it is, Americans can’t simply wake up and say “Hey, let’s be allies!” We have to confront our checkered shared history, and take great care to treat India as a nation worthy of respect in both our rhetoric and the deals we conclude. India should be included in as many as possible of the institutions, organizations, and deals the U.S. creates — not just in Asia, but around the globe.

Finally, there’s the fact that many liberal Americans strongly dislike India’s current leader, Narendra Modi. Modi is seen as persecuting and excluding Muslims, and some observers put him in the same category as China’s Xi Jinping. While these concerns shouldn’t be minimized or dismissed, I’ll argue in a later section that shunning India as an ally would be exactly the wrong way to address this.

Neutralize lingering, unnecessary conflicts

Making a closer, more explicit partnership with India, and drawing it decisively out of Russia’s orbit, would be the biggest diplomatic revolution the U.S. and our allies could pull off. If successful, it would leave China, Russia, and their small coterie of satellite states facing off against a coalition of democracies that overmatched them in terms of population, GDP, and military power. That coalition would be able both to guard the world against military aggression and to uphold the regime of human rights and positive-sum trade that has seen the world grow so much freer and richer since 1945.

But in addition, there are lots of other smaller conflicts that the U.S. should seek to resolve as part of this diplomatic revolution. Frictions with the leftist regimes in Cuba and Venezuela, and especially the lingering conflict with Iran, consume American attention and energy and create openings for Russia and China to expand their network of client states. Dispensing with these conflicts would allow America to focus on containment of Russian and Chinese power.

First, end the embargo against Cuba and open trade and immigration links with that communist country. The embargo has obviously failed to change Cuba’s regime in all its decades of application — in fact, by convincing the Cuban people that their economic woes are America’s fault, it probably solidifies the regime’s control. Opening up to Cuban people and goods won’t make them ditch communism in a day, but it’ll remove one potential Russian/Chinese ally in America’s backyard, while offering the Cuban people the chance at a brighter future.

Similarly, Biden should end sanctions on the impoverished basket-case country of Venezuela, and establish friendly relations with its president, Nicolas Maduro. Maduro has obviously been making overtures in this direction, and Biden should repay these with rapprochement. This will not only give Venezuela a chance to climb out of the deep economic hole that the policies of Maduro and his predecessor Hugo Chavez dug for it, but it’ll also prevent Venezuela from becoming another Cuba.

Finally, the U.S. should make a good-faith effort to reduce conflict with Iran. Actually pulling off another diplomatic revolution and allying with Iran would probably be a bridge too far, given that regime’s dependence on anti-American rhetoric for its domestic and regional legitimacy. And also, partnering with Iran would draw us back into the quagmire of the Middle East, which is a region that the U.S. has few strategic interests in, and which needs some time without great-power interference in order to work out its problems in seclusion. Instead, we need to extricate ourselves from the Middle East as completely as possible, in order to focus on the true global threats of the totalitarian great powers threatening Europe and Asia.

This will be best accomplished by making a deal with Iran that will allow the U.S. to shift to a posture of neutrality in the Middle East. (The Saudis will be mad, but that’s fine. They’re going to keep selling oil to the world no matter what we do, and we really don’t need them to do anything else.)

High-horse morality vs. blunt necessity

All of these moves — allying with India, rapprochement with old enemies in Latin American and the Middle East — will run into opposition from liberal internationalists who believe that the U.S. should penalize and punish human rights abuses and anti-democratic governance in all of these countries. They will decry Modi’s persecution of Muslims, Maduro’s assumption of dictatorial powers, Iran’s human rights abuses and proxy wars. They’ll also raise this objection regarding the authoritarian governance of Vietnam, another Asian country that the U.S. needs to forge an alliance with. The liberal internationalists will ask: If we choose to ally with such people and such regimes, how are we making the world safe for democracy?

And the answer is: Because the fight for human rights and democracy is not helped by purity tests. Pragmatism in the defense of liberty is no vice.

Consider our successes in the 20th century — first over the forces of fascism, then over communism. In both cases, we allied with regimes that were not simply authoritarian, but nightmarishly totalitarian. Joseph Stalin, our chief ally against Hitler — and without whom it would have been impossible to win the war without using nukes — was the second-worst dictator in the world at the time. We allied with him because he helped us beat the worst dictator. Similarly, in the 1970s, China was in the midst of the Cultural Revolution, an episode of chaotic totalitarian insanity that killed millions — and yet we partnered with them to oppose the Soviets, because the Soviets were a bigger and more powerful totalitarian threat. Stalin and Mao were both infinitely worse than Modi or Maduro or Khamenei, but we allied with them anyway.

And we ultimately won both of those titanic conflicts. Not without cost, of course — Soviet domination of East Europe after WW2, and entrenchment of CCP rule in China after the Cold War, probably resulted in a lot of human suffering. But the alternatives were worse in each case. The world is full of powerful monsters, and sometimes it’s simply necessary to partner with the less monstrous.

In addition, taking weaker authoritarian regimes under our wing sometimes — though certainly not always — helped eventually nudge them toward democracy and liberalism. South Korea was a fairly brutal dictatorship until the 1980s — now it’s a beacon of liberal democracy. If the U.S. hadn’t been South Korea’s indispensable patron and ally in the 80s, the military dictatorship might have simply crushed the pro-democracy protests with extreme brutality, as Iran has done several times in recent years. A number of other previously dictatorial or even genocidal states the U.S. has partnered with — Taiwan and Indonesia, for example — have also made the leap from dictatorship to democracy. This obviously doesn’t always happen, but the possibility is one more reason not to be too eager to shun countries with nasty governments.

It’s time to recognize that the unipolar hegemony the U.S. and our close allies enjoyed in the 1990s is gone, and will not return for a very long time if ever. We simply do not have the luxury to get on our high horse and try to ostracize everyone who doesn’t live up to our declared standards — never mind the fact that with the Iraq War and the Trump presidency, we proved that we ourselves don’t always live up to those standards. If we try to make every country without a perfect Freedom House score into a pariah, it is we who will become the pariah — and the world will be ruled from Beijing and Moscow.

The high-horse mentality serves no one except the preening self-satisfaction of a few misguided foreign policy thinkers. When we faced major threats, we have always allied with the second-worst against the worst, and this approach has served both our own interests and the cause of general human freedom and prosperity. If the U.S. is to capitalize on the geopolitical gains that the valiant Ukrainian defenders and bold European leaders have made in the last few weeks, we need a diplomatic revolution. And that revolution must be guided by pragmatism rather than purity tests. The world is now locked in a struggle that democracy can’t afford to lose.

Modi is India’s Prime Minister, not President.

India does have a President who is elected by the central and state legislatures, but is mostly a ceremonial figure, with no real power.

Comparing Modi to Xi is emblematic of the ignorance and condescension that is embedded into how even people who might claim to be “India hands” view India.

Xi is a dictator. Modi, on the other hand, has won election after election since 2002, but has worked his ass off to win those votes. He has then governed as both a moderniser and a welfare-statist focused on getting Govt benefits directly into the hands of the poor. And it is they who are his most ardent supporters, even more than urban Indians, who where his party(the BJP)’s base originally.

5 Indian states with a collective population a little less than that of the US just concluded in India, with the results out yesterday. Modi’s party was the incumbent in 4 of them and won all 4 handily; they got clobbered in the 5th (Punjab), but have always been a marginal player there. One of these states (Uttar Pradesh) has 220M people, and has never re-elected a state government since 1985. And in fact, most Indian states rarely re-elect their state Governments, which is why this lack of anti-incumbency is so astonishing, even to veteran observers of Indian elections. And no one doubts that it was Modi that was the deciding factor in all these states.

For now, Modi IS India.

This reinforces my belief that I, and every other patriotic Indian, need to work to strengthen the Modi government and the Hindi base as much as possible. Otherwise India would end up becoming a satellite state, susceptible to be bullied by American liberals -- who will gain much more prominence in coming years. We must do everything we can to empower and strengthen the Indian right further to negate the American influence as much as possible.

Second, a miscalculation in this post is that current Indian government is "forced" to choose sides because of dependence on Russian military equipments. That assertion ignores the fact that Modi was sanctioned and had his US visa denied before becoming the prime minister. He is totally aware of the danger American liberals pose to everything from India's national security interest to family values. India would have abstained, irrespective of its dependence on Russia.

I wish India could make it clear that time-tested friendship with Russia is not up for sale. But the current diplomatic and geopolitocal realities doesn't allow for that. Nevertheless, the Indian political establishment need to be more careful of the United States and stay wary of it going forward.