"Threats to the dollar" are just scare stories

BRICS, petrodollars, alternative currencies, and other things you shouldn't worry about

One of the most common questions people ask me is some variant of: “Is the U.S. dollar going to lose its dominance?” Variations on this include:

Will the BRICS overthrow the dollar?

Will the end of the petrodollar spell the end of dollar dominance?

Will alternative currencies replace the dollar?

What if countries diversify their reserves away from the dollar?

The answers to these questions are: 1) No, 2) No, 3) No, and 4) That would be a good thing.

Lots of people seem to think of international finance as a sort of power struggle — whoever’s currency is dominant, or strong, wins. Thus, when Americans read stories alleging that some new threat is about to overthrow the dollar, they worry that this spells the decline of the U.S. as a country, or at least of U.S. economic strength.

In fact, this is just not how things work. The U.S. does derive some benefits from the fact that countries tend to hold a lot of dollar-denominated reserves, but it also pays some very important costs. It’s likely that both the U.S. and overall global stability would benefit from a more balanced international financial system. But that having been said, it’s also the case that most of the “threats to the dollar” that get discussed in the financial press are vastly overhyped.

So let’s talk about each of these scare stories, and why each of them is highly implausible. And then at the end I’ll talk a bit about why the U.S. should want to see other countries diversify their reserves away from the dollar to some degree.

The BRICS are not really a thing

In 2001, a Goldman Sachs economist named Terence James O'Neill, Baron O'Neill of Gatley — known to most of us as “Jim” — created one of the most annoying economic memes of all time, when he grouped Brazil, Russia, India and China into a grouping called the BRICs. Later someone decided that Africa should be represented on this list, and so South Africa was added to make the BRICs into the BRICS.

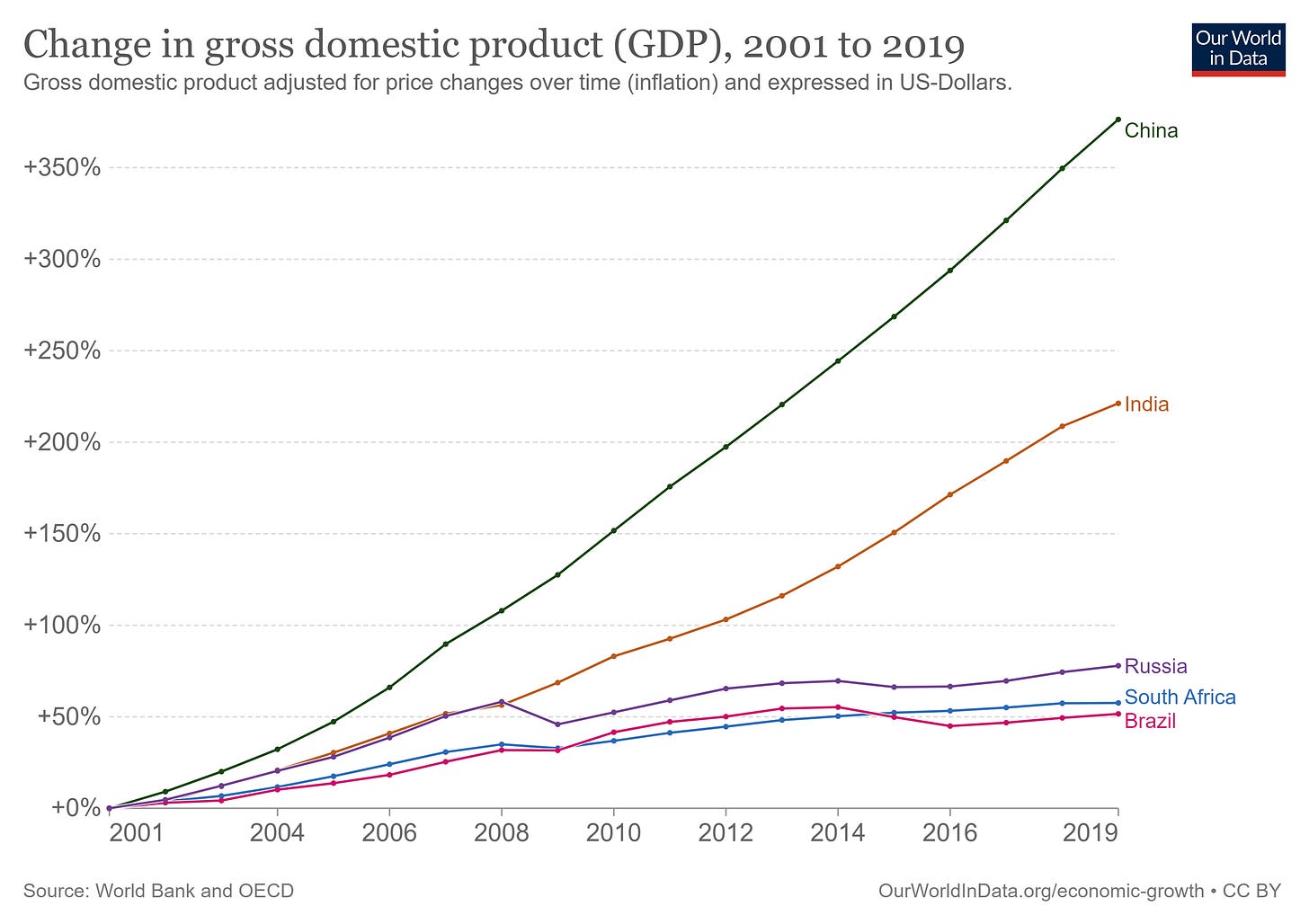

Essentially, this was a group of large countries that Jim O’Neill expected to grow a lot over the coming decades. That didn’t exactly pan out; China and India fulfilled their promise, but the others merely puttered along.

Unfortunately, however, some of the leaders of these countries decided that BRICS might mean more than just an investment thesis; they decided that it was going to be a power bloc, a kind of new economic non-aligned movement that would wrest control of global economic institutions away from the U.S., Europe, and their allies. In 2009 they started meeting regularly and trying to think about how to create their own economic institutions — a New Development Bank to compete with the World Bank, a Contingent Reserve Arrangement to lend each other money in times of currency crisis (something the IMF usually does), a system of submarine fiber-optic cables, and so on.

This, too, did not end up working out. The New Development Bank has disbursed almost no loan money at all, causing Jim O’Neill to declare it a disappointment. When Russia invaded Ukraine in 2022, the NDB cut ties with it. The Contingent Reserve Arrangement has done basically nothing, and the BRICS Cable never happened.

Given this history, you should be extremely skeptical when you read stories like this one:

Russia is ready to develop a new global reserve currency alongside China and other BRICS nations, in a potential challenge to the dominance of the US dollar.

President Vladimir Putin signaled the new reserve currency would be based on a basket of currencies from the group's members: Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa.

"The matter of creating the international reserve currency based on the basket of currencies of our countries is under review," Putin told the BRICS Business Forum on Wednesday[.]

This is incredibly unlikely to happen. First of all, it would require Brazil, India, China, and South Africa to deepen their cooperation and solidarity with Russia, at a time when all of them appear to be edging away. If the BRICS’ own development bank cut ties after Putin’s invasion, what’s the likelihood that India, China, etc. will commit themselves to a joint reserve currency with Russia? Seems very low.

Such a joint reserve currency would also require India to tie its financial future to China. Since China is by far the biggest economy of the bunch, the yuan would dominate any BRICS reserve currency in practice, meaning that capital inflows and outflows into the rupee via the new reserve currency would be determined by the policies of the People’s Bank of China. Given that India generally has quite high tensions with China — Modi has banned many Chinese tech companies, and used the 2021 BRICS summit to raise questions about the origins of COVID-19 — this seems unlikely.

Finally, a joint reserve currency gains China little over simply opening up its own capital account and allowing the yuan to be a major reserve currency. China could certainly do this at any time, but it would then sacrifice its ability to regulate capital inflows and outflows and control its exchange rate. China’s leaders are notoriously afraid of capital inflows that would push up the value of the yuan and make Chinese exports uncompetitive, and they’ve also acted in dramatic fashion to stop capital outflows from causing a currency crash. So I highly doubt China is going to want the yuan to be like the dollar any time soon.

In other words, the notion of BRICS creating a reserve currency to replace the dollar is vaporware, cooked up by Putin to try to get other countries on his side in his struggle against Europe.

Petrodollars are not important

When hearing scary stories about the overthrow of the dollar, you may have heard the word “petrodollar”. The finance blog world is peppered with stories with titles like “The End of the Petrodollar?”, “Why the End of the Petrodollar Spells Trouble for the US Regime”, and “Preparing for the Collapse of the Petrodollar System, part 1”.

The first thing to understand is that there is no currency called a “petrodollar”. Petrodollars are just dollars that are used to pay for oil. What happens is this:

Oil exporters like Saudi Arabia sell oil for dollars.

The oil exporters then use those dollars to buy assets like U.S. Treasury bonds.

When people talk about the “end of the petrodollar”, they mean one or both of the following:

Oil exporters selling oil for some other currency, such as yuan, and/or

Oil exporters investing their earnings in other countries’ assets instead of Treasuries.

Either of those things would reduce global demand for dollars. If oil exporters demanded to be paid in yuan instead of dollars, then countries would need to buy yuan instead of dollars in order to pay the oil exporters. And if oil exporters still got paid in dollars but decided to invest their earnings in non-dollar assets, they would have to sell the dollars for other currencies (e.g. yuan) in order to do so; this would also reduce the demand for dollars.

First of all, oil exporters are unlikely to switch to the yuan, either in terms of payments or as a place to stash their reserves, for reasons discussed above. It would require China to allow capital inflows and outflows, which it doesn’t want to do.

But more importantly, petrodollars are just not a big deal in terms of dollar demand. Saudi Arabia’s total forex reserves are only $471 billion, a bit smaller than Taiwan’s. Russia, due to financial sanctions, is no longer a factor here.

As for the dollar demand needed to actually make oil purchases, that’s not a big deal either. OPEC’s whole net oil export revenue is about $397 billion per year, and the number of dollars countries need to keep handy in order to buy that oil is going to be less than that.

In other words, petrodollars are just not a huge deal. People who claim that the petrodollar system provides the “backing” for the dollar, as some kind of new oil-based gold standard, don’t really know what they’re talking about. You should not listen to them. Instead you should read this Investopedia article by James Chen, explaining, once again, that the dollar does not depend on petrodollars. The bottom line here is that oil is not the reason people hold dollars.

Alternative currencies are not happening

A third “threat to the dollar” that you sometimes see getting discussed in the press is the rise of alternative currencies. These include:

Bitcoin

stablecoins

gold

Central bank digital currencies (CBDCs)

various other things

For example, I see scattered reports that Russia and Iran creating a gold-backed stablecoin for use in trade between the two countries. If throwing “Russia and Iran”, “gold”, and “stablecoin” into a story sounds like Mad Libs, well, that’s because it is. Russia and Iran have no reason to use blockchains to carry out trade between their countries, and if they did, they could just use Tether. A medium of exchange between Russia and Iran does not need to be “backed” by anything, including gold — it’s just a system for exchanging goods and services between the two. And for this hypothetical gold-backed stablecoin to displace the dollar in any way, a bunch of countries would have to buy the coin, which they would have little reason to do, since if they want to trade with or invest in Russia and Iran they can just buy rubles and rials. In other words, “Russia and Iran create a gold-backed stablecoin” is just another case of Putin throwing nonsense at the wall and seeing what sticks.

Equally as ludicrous is the idea that a proposal for a common currency between Brazil and Argentina would represent any sort of challenge to the dollar. First of all, why any country in its right mind would want to tie its monetary policy to Argentina’s, I don’t know. But more importantly, this currency would be an extremely minor player compared to things like the euro, the yen, the pound, and the won, which are already alternatives to the dollar.

As for central bank digital currencies (CBDCs), they’re not actually new currencies, just payments apps — state-sponsored versions of Venmo or Zelle. I explained in an earlier post why they’re not a big deal:

Bitcoin is not going to replace the dollar; even ignoring all the problems with energy usage and transaction difficulty, no one is going to choose a reserve currency that people don’t even use to buy pizza and beer.

As for gold, it’s something that countries can (and do) use to diversify their reserve holdings. So in that sense, it is a minor “threat to the dollar”. But in fact, reserve diversification is not a threat at all; it’s a good thing.

Reserve diversification is good for the U.S.

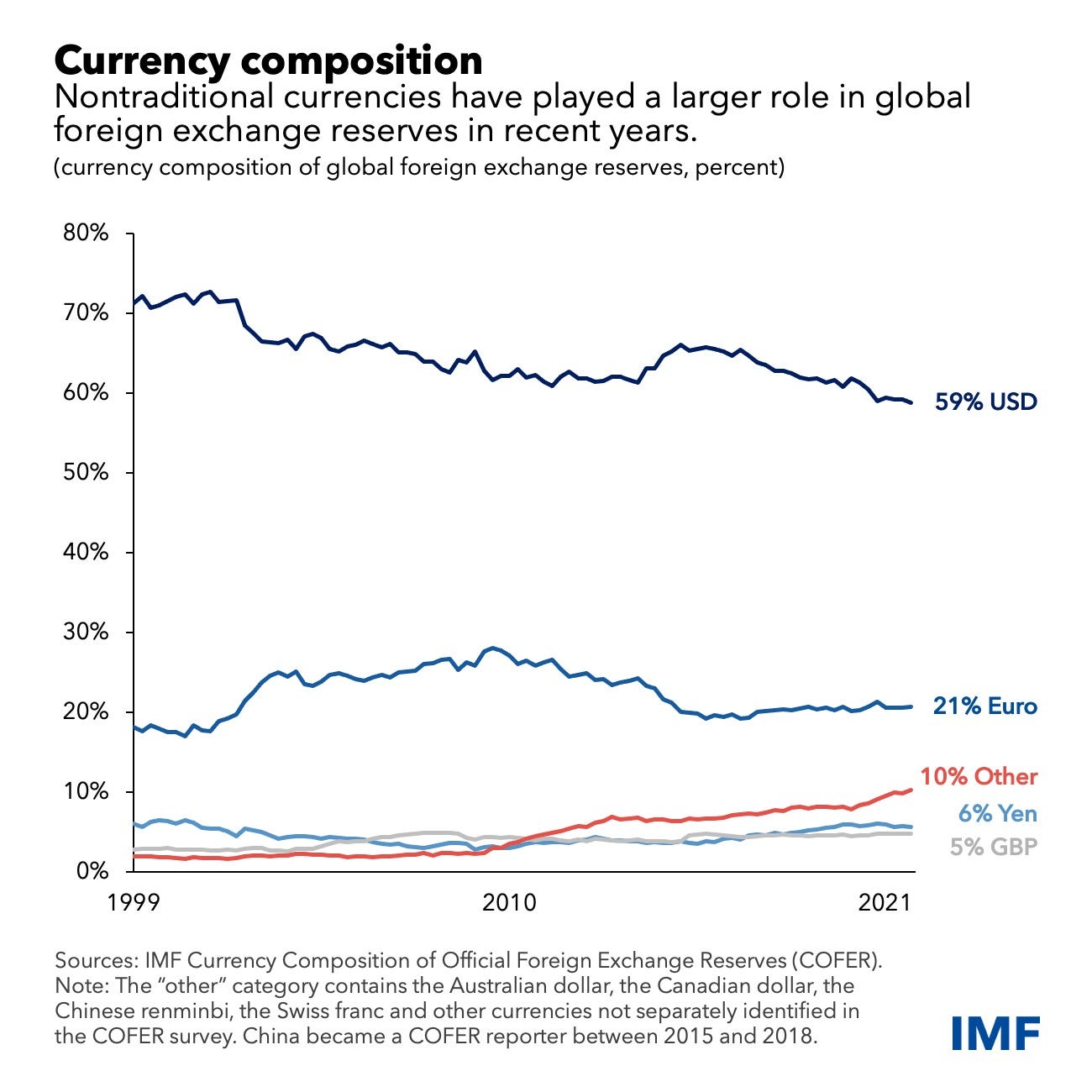

This brings us to the final “threat to the dollar” — reserve diversification. Since the turn of the century, there has been a downward drift in the percent of global foreign exchange reserves held in dollars:

Countries’ central banks also hold gold reserves, which aren’t pictured here. China, Russia, and Turkey have built sizeable gold holdings over the last two decades, but most of the gold held by central banks is still held by the U.S. and Europe.

A recent IMF report shows that recent diversification out of the dollar is being driven largely by diversification into other currencies — a little bit into the yuan, but largely into currencies like Canadian and Australian dollars, South Korean won, Swiss francs, etc. This is highly unlikely to spell the death of the dollar as a major reserve currency, or even as the major reserve currency. But it does erode dollar “dominance” of international finance.

And guess what? That’s a good thing.

We use words like “strong” and “dominant” to describe an expensive dollar that’s in high demand. But those words give the phenomenon a positive connotation that it doesn’t deserve — they create the false impression that a “strong” and “dominant” dollar means a strong U.S. economy and dominant U.S. power in the world. Neither one is true.

In a post a year ago, I explained why a “strong” dollar weakens our export industries (including manufacturing), and pushes our country toward financialization:

[A strong dollar] creates some benefits for America — the so-called “exorbitant privilege”. Holding dollar assets means lending money to American borrowers, so the fact that countries want to hold a bunch of dollar assets means that Americans get to borrow cheaply. This could include American companies looking to borrow money in order to do stock buybacks (or invest in business expansion), American consumers looking to get cheap mortgage loans, or American banks looking to borrow cheaply in order to make more loans.

Great, right? Except this also makes American exports much more expensive overseas, because higher demand for dollars makes the dollar more expensive. This “strong dollar” is one reason for the U.S.’ large and persistent trade deficit…This pushes the U.S. away from export industries like manufacturing, and toward industries that benefit from cheap borrowing — finance, real estate, etc. In other words, the strong dollar is probably one culprit in the financialization of the U.S. economy.

As for U.S. power, it’s true that the ubiquity of dollar-based payment systems allows the U.S. to threaten financial sanctions like the ones it recently imposed on Russia. That is a form of power, though it’s not America’s primary or most important weapon. But note that the dollar, euro, and yen together are far more dominant than the dollar alone. And note that most of the currencies that central banks are diversifying into are also U.S. allies — Canada, Australia, South Korea, and so on.

There is only one currency in the world that could ever really threaten the combined financial power of the U.S. and its allies, and that is the yuan. If China ever decided to float its currency and open its capital account, then yes, the currency of the world’s biggest manufacturer and biggest exporter might indeed supplant the dollar as the world’s reserve currency, and yuan-based payment systems might indeed replace dollar-based payment systems across the globe. It might be similar to the transition from the British pound to the U.S. dollar a century ago. Or failing that, at least it might result in a bifurcated financial system, with China as a fierce peer competitor to the U.S. and Europe for control of global payments systems, capital flows, and financial leverage.

But given China’s unwillingness to give up control over its currency’s value against the dollar and euro, and over capital inflows and outflows, this one real challenge to the dollar doesn’t seem likely to materialize soon. Thus, all of the scare stories you hear are wrong, and the mild diversification out of the dollar that you read about in the news is a good thing for the U.S.

Thank you so much, Noah! It's so annoying to see people freaking out about shit they don't understand.

No one would ever trust that a floated Yuan would stay that way. China operates at the whim of its current dictator--sometimes stable, sometimes feckless.