The U.S. needs a Latin America policy

It's time to be a Good Neighbor once again.

It was somewhat overlooked in the hubbub of war news from Ukraine, but President Biden took a potentially important diplomatic step recently. With sanctions on Russia threatening to send oil prices into the stratosphere, Biden sent a delegation to Venezuela to discuss easing the sanctions on that country’s oil industry. Venezuela responded by releasing a pair of imprisoned Americans.

The outreach toward Venezuela is a purely strategic move, born of the necessity generated by the West’s conflict with Russia. With a nuclear-armed totalitarian great power on the rampage, the U.S. is far less able to prosecute more minor feuds with smaller countries. Predictably, Biden’s move drew condemnation from various politicians still wedded to the old high-horse moralistic foreign policy of the unipolar moment, as well as from conservatives for whom fighting leftism in Latin America is still a priority. Hopefully Biden has both the resolve and the political strength to resist this criticism and push through with a general diplomatic revolution.

But beyond that general imperative, the Venezuela talks give the U.S. an opportunity to change its general policy toward Latin America. Although the U.S. interferes with its southern neighbors far less than during the Cold War, it still sometimes punishes Latin American countries for embracing leftist regimes. The continuing embargo on Cuba and the sanctions on Venezuela (mostly implemented by Donald Trump) are the two main examples. The Trump administration also promoted the narrative that the reelection of socialist president Evo Morales in Bolivia in 2019 was fraudulent — which resulted in a coup — even though evidence of fraud was never found (Morales’ party came back to power when democracy was restored a short time later). The U.S.’ backing of a rival claimant to the Venezuelan presidency is also questionable.

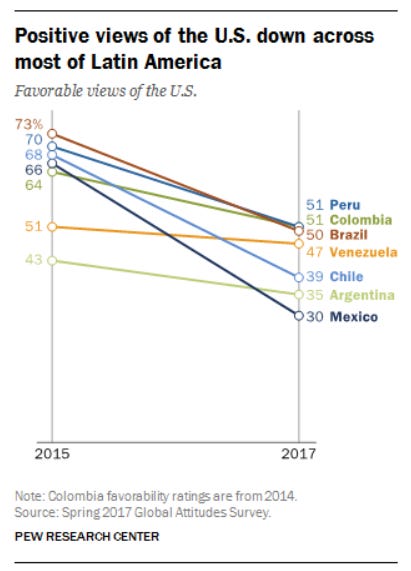

Much of this was Trump’s doing. Latin America opinions of the U.S. rose sharply in the late 1990s and remained generally favorable through the Bush and Obama administration, but plunged when Trump took office:

But although it’s easy to blame things on Trump, he’s not the only one whose approach toward Latin America is mentally influenced by the lingering shadow of the first Cold War. For example, Democratic Senator Robert Menendez condemned Biden’s outreach to Venezuela:

“Nicolás Maduro is a cancer to our hemisphere and we should not breathe new life into his reign of torture and murder,” Menendez said in a statement. “The Biden administration’s efforts to unify the entire world against a murderous tyrant in Moscow should not be undercut by propping up a dictator under investigation for crimes against humanity in Caracas.”

And Republicans, especially in Florida, have also condemned the move. Florida Republicans are also some of the biggest supporters of the continuing, futile Cuba embargo, and of opposition to Latin American leftism in general.

This attitude could potentially lead to further friction between the U.S. and Latin American countries that choose leftist leaders. And most Latin American countries are, in fact, choosing some flavor of leftist leader. Here’s a recent map from The Economist:

But as the Economist article explains, these so-called “leftists” are actually an incredibly heterogeneous bunch. Gabriel Boric, who was recently elected in Chile, calls himself a “libertarian socialist” and is really more like an American social liberal. Colombia’s Gustavo Petro is a strong critic of Maduro’s anti-democratic moves in neighboring Venezuela. Brazil’s Lula, now leading in the polls, was very moderate during his earlier term as President from 2003 to 2010. And so on. In fact, that these leaders are all lumped together as “leftists” is itself partly a relic of the Cold War.

So it’s worth asking: Why is Latin America electing so many left-of-center leaders? Partly it’s just a coincidence; as in the U.S., these countries’ politics tend to swing back and forth, and the swings just happen to be mostly synced up right now. But partly it’s because the region’s main economic challenge is to decrease inequality.

Americans tend to think of Latin American countries as “developing”, but in fact most of them are in the middle income range.

Except for a few small poor countries like Honduras, Nicaragua, and Bolivia, these are mostly in an income range well above, say, India, or most countries in Africa. But they’re also not generally growing that quickly. These countries’ economies are generally pretty based on natural resources and agriculture, which doesn’t lend itself to the kind of fast exponential growth seen in places like Bangladesh or Vietnam. Frankly, that’s unlikely to change anytime soon (though I’ll write a post later with some ideas about how Latin America could make the jump to manufacturing).

But these countries also tend to have another big problem: Deeply unequal economies. The phrase “Latin American levels of inequality” is a cliché for a reason. Here are the Gini coefficients for most of the LatAm countries that have elected (or look likely to elect) left-of-center leaders, with Vietnam, Bangladesh, and the U.S. included as a reference:

You can see that inequality in these countries is really high — even higher than the U.S., and substantially higher than in fast-growing low-income Asian countries.

If your income is already at a middling level, and your growth is slow and incremental and expected to remain so for the foreseeable future, and your society is vastly unequal, then the best thing you can do to improve quality of life for the masses is to bring down inequality. And in fact, most Latin American countries have been doing this successfully. You’ll notice that the Gini coefficients of most of the Latin American countries shown above start trending down around the early or mid 2000s. They’re still really high, but they’re making progress.

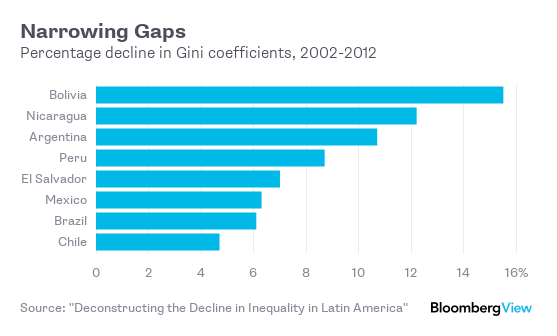

In fact, there’s a very good paper about this from 2016, by Lustig, López-Calva, and Ortiz-Juarez. Essentially there are two main reasons inequality has been falling in these countries: More equal wages (in part due to better education), and progressive transfers from the government. I made a graph of Lustig et al.’s data for Bloomberg a while back:

This is a success story. It means poverty is falling in some of the world’s most unequal countries, even through overall growth has been very modest. And that’s naturally a trend that most people in Latin America would like to sustain — since inequality is still so high, there’s probably scope for further decreases.

Of course, Venezuela’s experiment with leftism has been an absolute disaster. Chavez and Maduro starved the state-owned oil company (PDVSA) of needed investment, engaged in arbitrary nationalizations of businesses, and responded to inflation with price controls that simply made the situation worse. As a result, Venezuela has now suffered an economic collapse so stark it rivals the devastation of a war.

But notice that not every socialist regime in Latin America has produced the same results. Evo Morales, though his rhetoric was as fiery as Chavez’, governed far more responsibly. During his tenure, Bolivia’s GDP per capita rose by half:

And as you can see from the chart above, Bolivia simultaneously saw one of the region’s biggest drops in inequality.

So even among self-declared “socialists” in Latin America, there’s considerable heterogeneity. And yet the Trump administration still tried to accuse Morales of election fraud, which encouraged a coup that almost ended up abolishing the country’s democracy.

That was obviously a mistake — the exact kind of behavior we should have left behind in the first Cold War, and the kind of thing that caused the U.S.’ image in the region to plummet. And if a second Cold War against Putin and his authoritarian allies is now beginning, we can ill afford to alienate the countries in our own hemisphere.

Fortunately, there’s an alternative. It’s called the Good Neighbor policy, and it was implemented by FDR during his term in office. FDR’s Good Neighbor policy was essentially a policy of non-intervention, coupled with positive propaganda in both the U.S. and Latin American countries to promote the idea of hemispheric concord. It replaced the gunboat diplomacy that the U.S. had used to bully Latin American countries in the decades prior. As a result of the shift, Latin America strongly supported the Allies in World War 2, securing the Western Hemisphere from any Axis influence.

In the Cold War this policy was unfortunately abandoned, and the U.S. essentially returned to gunboat diplomacy with frequent interventions against leftist regimes in Latin America. After the Cold War ended, the Clinton, Bush, and Obama administrations informally moved back in the direction of FDR’s hands-off approach, which caused the rebound in the U.S.’ image down south. But as the continued fruitless embargo on Cuba shows, we never completely switched back. And then Trump came along and moved back toward interference.

The U.S. needs to return to the Good Neighbor approach — not just informally, but formally. The embargo on Cuba should end immediately and completely. Sanctions on Venezuela should similarly be dropped. And the U.S. should explicitly declare its intention not to interfere with Latin American leaders whose ideology it frowns on. We should make it clear that all countries should be free to choose what kind of regimes they want to be ruled by — even if that means electing catastrophically bad leaders like Chavez.

And what of leaders who aren’t elected? Cuba is a dictatorship, and Venezuela essentially one as well. These regimes have done some odious things. The U.S. should use rhetoric and diplomacy to encourage Latin American countries to allow free and fair elections and safeguard human rights. But time and again, economic punishment has proven an ineffective tool for forcing our neighbors to embrace liberal values. So our democracy promotion should remain confined to rhetoric, and to promises of favorable trade deals, with no “stick” involved.

The fact is, Latin America needs to continue its successful push against inequality. And this is probably going to involve a lot of “leftist” leaders. That’s OK. Cold War 1 is long over, and the world is no longer divided into opposing ideological blocs. Our world is in a different kind of conflict now, and just as in FDR’s time, we need to make sure the Western Hemisphere is completely friendly.

I still don’t understand why we can go to Venezuela (with all its potential for domestic political blowback, congrats on ur reelection Rubio) and we can’t make it clear to the Saudis and jumped up gulf princes that either they get the oil Wells pumping or kiss goodbye to the fleet in the gulf, any weapons deals & all those US Bases

Can we distinguish between "we'll sell phones, even to people ruled by dictators" and "we'll loan money, even to dictators"? I dislike the idea of Wall Street becoming a piggy bank for the next Ortega or whomever.

Money is a good way for dictators to stay in power. Is it really a good idea for us to open our wallets wide even to the worst governments?

Or am I naive to try to separate "trade" from "finance"?