The "corporate feudalism" thing won't work

Warrenite progressives are not going to catch populist fire by bashing corporations.

Nothing unites feuding factions like losing. For years, the Bernie leftists and the Warren progressives were at each other’s throats, competing viciously for the mantle of standard-bearer for a generational wave of popular unrest. Despite the fact that Warren’s 2020 campaign crashed and burned and Bernie caught much more fire with the youth, Warren actually won that battle — her ideas and her allies had an incredible amount of intellectual, ideological, and backroom institutional influence in the Biden administration. The Biden administration was, in some ways, a Warren administration.

Now progressivism in general is on the outs. And both the Warren and Bernie wings of the left have united to attack a new foe — the Abundance Agenda, championed by center-left types like Ezra Klein, Derek Thompson, and Matt Yglesias. The Bernie people mostly either just hurl sarcastic insults, or mischaracterize the abundance faction as being “neoliberals” who just want to deregulate. (They didn’t read the book, and it shows.)

The Warrenites, however, are a more intellectual lot, and they have coalesced around a coherent critique of the abundance idea. In their view, it ignores corporate power. Abundance liberals want more housing, more energy, more transit, more health care, more everything, and they’re pretty agnostic about how we get there. Derek Thompson summed up his point of view in a recent interview:

But Warrenites care very much about how we get to abundance. If building more housing, energy, transit and health care enhances the power and/or boosts the profits of large corporations, then Warrenites think it’s not worth it.

Zephyr Teachout, a Fordham law professor, sums up this attitude in her review of Abundance:

If we just…took on the real bureaucratic behemoths of today—the private equity cartels and the monstrous platform monopolies like Google and Meta—we would unlock far more innovation and creativity and vitality…My view then, and now, is that to transform a bloated corporate feudal system into a dynamic one, we need to break up feudal power[.]

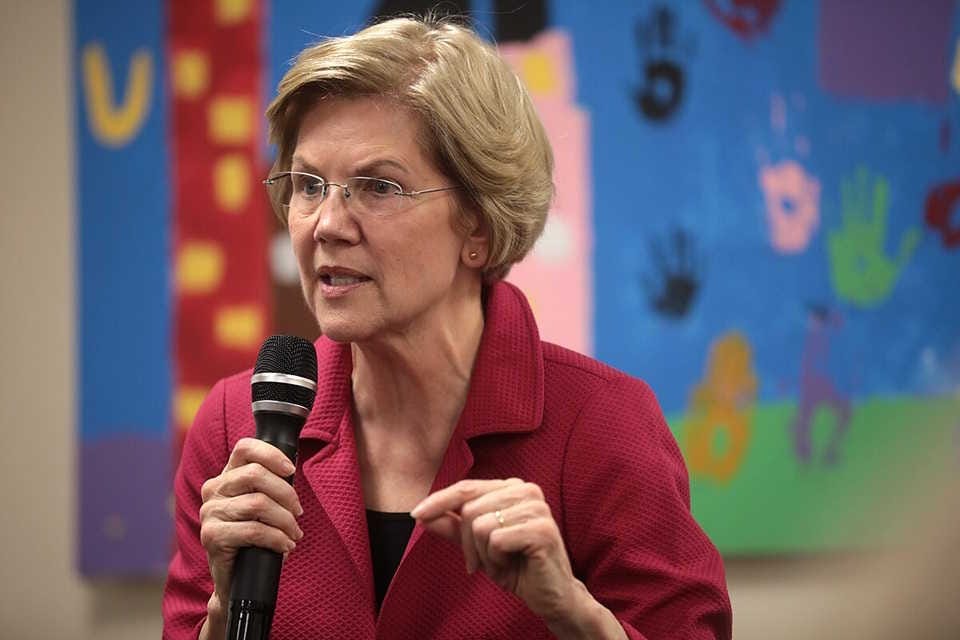

This notion of corporate feudalism as America’s biggest problem animated many of the policies of the Biden administration. Elizabeth Warren blamed corporate power (“greedflation”) for the post-pandemic inflation, and called for price controls as a solution — a call that both Biden and Kamala Harris echoed at least to some degree. Biden FTC chair Lina Khan’s approach to antitrust, which focused on corporate power instead of on consumer welfare, was squarely in this tradition. Biden’s DOJ and FTC both aggressively targeted big tech companies like Meta, Google, Amazon, and Apple.

It didn’t help. Neither the Biden administration nor the Harris campaign ever really sparked populist fire among the American public. All the rhetorical and policy assaults on big corporations failed to prevent significant numbers of working-class Americans (especially working-class Hispanic and Black Americans) from defecting to the GOP. The Warrenite anti-corporate approach was populism without popularity — an elite intellectual project that was mostly wrong on the actual economics while also failing to spark enthusiasm among voters.

I can’t think of a worse combination than populism without popularity. It’s abundantly (heh) clear at this point that banging on about the evils of big companies is not going to rouse the American public. And this is particularly ironic because at a time when Trump’s tariffs are smashing the American economy, inflation is raising the cost of living, and Elon Musk’s DOGE is preventing crucial government functions from functioning, there is plenty of economic stuff that regular people are actually mad about.

The fact that a bunch of progressive lawyer types are still laser-focused on Meta and Google at a time like this simply illustrates how completely out-of-touch they are with what’s really ailing the American masses.

Antitrust is just not going to rouse the masses

Throughout the 2010s, I supported stronger antitrust, as did many other people in the general econ world. Although the evidence wasn’t definitive, there was a lot of circumstantial support for the idea that excessive corporate concentration was holding down wages and possibly holding back growth and innovation as well. Antitrust, in the form of closer scrutiny of M&A and the occasional prosecution of a monopolist, seemed like the natural remedy.

But the “Neo-Brandeisians” like Lina Khan, who dominated antitrust thinking in the Warren movement and the Biden administration, had a different idea. My reasons for supporting stronger antitrust were economic in nature — I was worried about prices, wages, and growth. The legal scholars who made up the Neo-Brandeisian movement worried that if companies got too rich and powerful, they’d take over the country. In other words, econ types like me were worried that economic power would lead to negative economic outcomes; the Neo-Brandeisians worried that economic power would translate into political power.