The AI bust scenario that no one is talking about

Even if AI works, and even if it gets adopted very fast, it might not make profit.

I’ve actually already written a number of posts about the possibility of an AI bubble and bust. Back in August, I wondered if the financing of data centers with private credit could cause a financial crisis if there was a bust. I followed that up with a post about profitability, and suggested that the AI industry might be a lot more competitive than people expect. In October, I wrote about how AI is propping up the U.S. economy.

But I feel like I need to write another post, because almost all of the discussion I see about an AI bubble seems to leave out one crucial scenario.

Since I wrote those posts, popular belief that there’s an AI bubble and impending bust has only grown. A lot of prominent people in the industry are talking about it:

“Some parts of AI are probably in a bubble,” Google DeepMind CEO Demis Hassabis told Axios’ Mike Allen at the [Axios] AI+ Summit on Dec. 4. But, he added, “It’s not a binary.”…“I, more than anyone, believe that AI is the most transformative technology ever, so I think in the fullness of time, this is all going to be more than justified,” Hassabis said…“I think it would be a mistake to dismiss [AI] as snake oil,” OpenAI Chairman and Sierra co-founder Bret Taylor said at the AI+ Summit…Taylor acknowledged that there “probably is a bubble,” but said businesses, ideas and technologies endure even after bubbles pop. “There’s going to be a handful of companies that are truly generational,” Taylor said.

And:

Every company would be affected if the AI bubble were to burst, the head of Google’s parent firm Alphabet has told the BBC…Speaking exclusively to BBC News, Sundar Pichai said while the growth of artificial intelligence (AI) investment had been an “extraordinary moment”, there was some “irrationality” in the current AI boom.

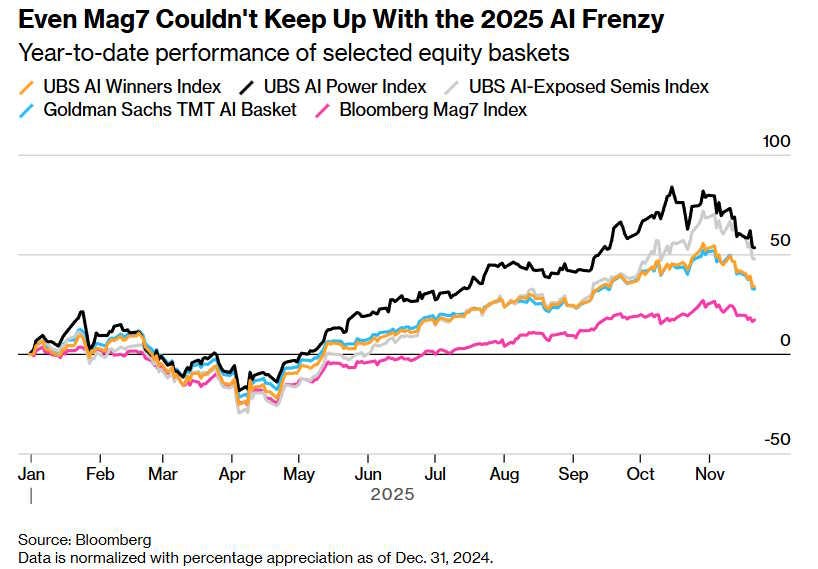

The market is also starting to get skeptical. Here’s a chart from Bloomberg:

Almost everyone I read is basically talking about two scenarios for an AI bust. I call these the Virtual Reality Scenario and the Railroad Scenario. I’ll go over these, and then talk about the third scenario

The Virtual Reality Scenario

What I call the Virtual Reality Scenario is if AI, in its current form, turns out to just not be a very useful technology at all — or at least, not nearly useful enough to justify the amount of capital expenditures. This might happen because AI hallucinates too much, or because progress in AI comes to a halt. Bloomberg reports:

The data center spending spree is overshadowed by persistent skepticism about the payoff from AI technology…[R]esearchers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology found that 95% of organizations saw zero return on their investment in AI initiatives…More recently, researchers at Harvard and Stanford [found that e]mployees are using AI to create “workslop,” which the researchers define as “AI generated work content that masquerades as good work, but lacks the substance to meaningfully advance a given task.”…

AI developers have also been confronting a different challenge. OpenAI, Anthropic and others have for years bet on the so-called scaling laws — the idea that more computing power, data and larger models will inevitably pave the way for greater leaps in the power of AI…Over the past year, however, these developers have experienced diminishing returns from their costly efforts to build more advanced AI.

This is basically what happened to VR technology. Meta spent $77 billion on developing the virtual reality “Metaverse”, but outside of gaming and some niche entertainment applications, nobody really wanted VR for anything, no matter how good the headsets got. Meta is now throwing in the towel and pivoting away from the Metaverse.1

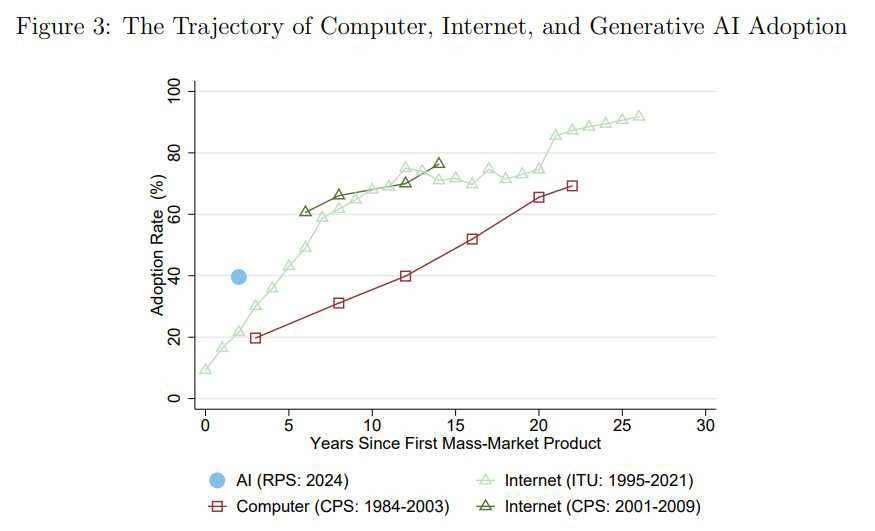

But I just don’t think this is going to happen to AI. Very few people use VR, even a decade after it started getting hyped. But AI is being adopted more rapidly than any technology in history. As far back as a year ago, 40% of people were already using AI at work:

Household adoption is similarly rapid.

Humans just know when a technology works. If AI weren’t useful, we’d see people trying it for a while and then setting it aside. But we don’t see that. Despite hallucinations and the other limitations of the technology, most people are finding some reason to keep using AI after they try it.

Sorry, haters. This tech is for real.

As for progress hitting a wall, I just don’t think that’s an important question anymore. The consensus in the industry2 seems to be that scaling up in terms of training AI models on more data has hit a wall, but that our ability to improve AI’s capabilities via inference scaling (basically, having it “think harder” before answering) is still going, and improvements in reinforcement learning and other algorithmic techniques are still coming.

But I don’t think this is the right question to be asking, because “better chatbots” are only one of many ways that AI can create value. The world of AI applications, including “agents” (AI that does stuff on its own) is still in its infancy. Andrej Karpathy is good at talking about this; I recommend his interview with Dwarkesh Patel.

Essentially, we haven’t even begun to build AI yet. Anthropic sort of has — it’s focused on AI business applications, and it’s making some money doing this. But most of the actual technology we’re going to create with AI is still in the future. And there’s a chance that AI as it exists today will be able to provide the foundation for a whole bunch of incredibly useful applications, even without any continued improvement in capabilities. The typical pattern is for most of the useful (and lucrative) applications to manifest decades after a new general-purpose technology is introduced.

The Railroad Scenario

Which brings us to the second scenario: the Railroad Scenario. Railroads were even more economically useful and lucrative than their biggest boosters in the 1860s imagined. But there was still a huge bust in 1873, because those economic benefits didn’t show up before railroad companies’ debt came due.

Here’s what I wrote about that back in October:

The railroad buildout in the 1800s was, in percentage terms, the greatest single feat of capital expenditure in U.S. history, dwarfing even what the AI industry is spending on data centers right now. In 1873, a bunch of railroad-related loans went bust, causing a banking crisis that threw the economy into a decade-long depression.

And yet despite the carnage in the railroad industry, the number of miles of railroad in the U.S. never stopped increasing — it just slowed down briefly and picked back up again!…In other words, the great railroad bust did not happen because America built too many railroads. America didn’t build too many railroads! What happened was that America financed its railroads faster than they could capture value…

There’s basically no technological limit on how many…loans [the financial system] can disburse in a short period of time…And yet there is a limit on how fast businesses can create real value. In order for a railroad to pay off, you need to build it, and then you need to find people to pay you to ship things on it. That takes time, especially because the full economic value of the railroad doesn’t manifest until new cities, new industries, and new supply chains that are enabled by the railroads get created.

Just to give one example, the famous Sears Catalog — which allowed people all across America to order products and have them delivered by railroad — eventually revolutionized American retail. But it didn’t even start to do that until 1888 — fifteen years after the big railroad crash of 1873…

Why is this important for AI? Because even if AI creates all the value its biggest boosters say it’ll do — supercharges growth, enables the automation of most kinds of production, and so on — it might not do it fast enough for the data center “hyperscalers” to pay back everything they borrowed. In that case, there will be a wave of defaults on bonds and loans.

We don’t know how likely this scenario is, because we don’t know how fast AI value creation will increase. But we can get some basic idea of the risk of this scenario by looking at the financing side.

If the companies building and operating the data centers (the main cost of AI) are spending less than they make, then everything is basically safe. Suppose you have a company that makes $50 billion in profit every year, and you spend $40 billion every year on data centers. Even if AI suffers a catastrophic crash and all your money is wasted, you’re safe; you just take a hit to your profit margins for a year, your stock price goes down, and then you just move on. This is true even if you borrowed the money to build the data centers; if things go bad you can afford to pay off the loans.

If you’re spending $70 billion a year things get dicey; you might have to take a couple of years of losses to pay back the loans if there’s a bust. And there’s some level of borrowing and spending where you’re actually in danger of bankruptcy. There’s no hard and fast rule for when a certain amount of spending becomes dangerous; it’s just sort of a sliding scale of worry.

Right now, much of the AI buildout is being done by big tech companies like Google, Microsoft, Amazon and Meta that make lots and lots of profit.3 Until recently, these “hyperscalers” have been making enough cash to cover their AI spending. But spending is rising, so that may not be true for much longer. If spending keeps increasing, some companies, like Amazon, may start to have to borrow against future cash flow soon. And Meta, which doesn’t have its own cloud business, and thus has to pay other companies to do its AI stuff, may be in greater danger.

Meanwhile there are a bunch of other companies that are investing a ton of money in AI that don’t make enough profit to fund it out of their own pockets, but which have borrowed a bunch of money to invest in AI. These include the big model-making companies — OpenAI, Anthropic, and xAI. They also include some cloud providers like CoreWeave that aren’t attached to a big profitable business. And they include various construction companies and service providers.

If AI takes 10 or more years to generate enough value to pay back all these debts, many of these companies could go bankrupt. Whatever financial institutions they’ve borrowed money from — private credit firms, banks, etc. — may fail or have to pull back significantly when their loans suddenly go bad. And that could touch off a financial crisis, even if AI continues to advance and companies continue to build data centers. That would be like what happened in 1873 with the railroads. AI itself would be fine, but the economy, the financial system, and a bunch of specific companies could be hurt.

This scenario seems at least fairly likely, given that this is basically what happened with both the railroads and the telecoms in past industrial booms. Currently, many observers are highly skeptical that AI companies will be able to earn enough revenue to pay back their debts by 2030, even under optimistic assumptions. As I said, the typical pattern is for the economy to take a long time to figure out how to use each new general-purpose technology, and the financial system may not be able to wait around.

But there’s also a third scenario, which relatively few people seem to be paying attention to. Even if AI works and manages to create value very quickly, that value may not be captured by the AI companies themselves. AI itself may turn out to be a commoditized, low-margin business, more like solar power…or airlines.