Social media destroyed one of America's key advantages

We used to be able to spread out. Now we're locked in with each other.

“Something there is that doesn’t love a wall” — Robert Frost

I still stick to my prediction that American society is slowly calming down from the unrest of 2014-2021. But as new rounds of protests erupt across the nation and Senators are wrestled to the ground and masked unidentified government agents rampage through workplaces and communities looking for “illegals” to arrest, it’s worth remembering that the decline of unrest can be very slow and bumpy. Thus it was in the 1970s, and thus it is today.

But why is American society so unsettled in the first place? Something clearly broke in our society in the early 2010s. Watching TV or reading books from before that time feels like looking at a fresco or a mosaic of a vanished golden age — a country that had its problems and disagreements, but which basically worked. A country that almost no one seemed to doubt was a country, and should be one.

What broke that healthy nation? In a post last year, I argued that a perfect storm of events — the housing crash and Great Recession, the rise of China, racial diversification, and the rise of smartphone-enabled social media — all came crashing down on America at the same time:

I think that story is right, but I don’t think it explains why America was especially vulnerable. Many other countries suffered from the global financial crisis, faced the rise of China, experienced tensions over immigration, and struggled with the introduction of social media. To give just one example, you can see a lot of the effects of smartphones — on attention spans and learning, depression, suicide, etc. — in other countries, not just the U.S.

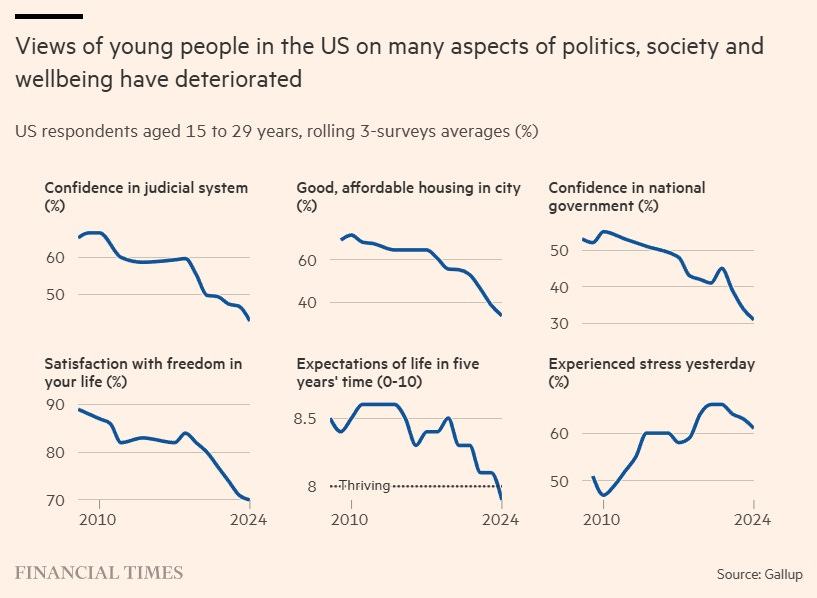

And yet the U.S. seems to have been uniquely wounded by the last decade and a half. Where other rich countries have mostly resisted the rise of authoritarian, demagogic leaders, the U.S. is stuck with Trump. American culture wars seem particularly pernicious and intractable. And America has suffered a particularly severe decline in the degree to which people trust institutions:

In fact, Americans are just down in the dumps about their country in general, and have been so for some time:

(Other polls find the same.)

This is especially odd in light of the fact that America’s economy is doing so remarkably well compared to other rich countries. Wealth is up above where it was before the Great Recession, the middle class is economically healthy and thriving, wages are rising steadily, and America’s macroeconomic performance has been very solid. The U.S. economy is an incredibly resilient machine — if you want a reason for optimism, look at how the economy has thrown off every shock and headwind that the world could throw at it.

And yet consumer sentiment is in the dumps. And if you tell people the economy is good they’ll get mad at you. I believe those low sentiment numbers, and I believe in that anger, but I don’t see how it can be the real economy causing them. Instead, I suspect that Americans are projecting their anger at their institutions — and at each other — onto economic issues.

The introduction of the smartphone — and especially, social media on the smartphone — seems to have something to do with it. These technologies became ubiquitous in the 2010s:

Not all of the problems in American society line up nicely with the introduction of smartphone-enabled social media. Severe political polarization began earlier, probably in the 2000s as a result of the Iraq War. Satisfaction with the direction of the country fell at about the same time.

But the fall in institutional trust, and the rise in mental illness and unhappiness, line up well with the rise of the smartphone. Back in 2023, Erik Hoel had an excellent post listing a bunch of things about America that got worse right around the time that everyone got Facebook and Twitter and Instagram on their phones:

Many of the trends Hoel notes are tangential to the point I’m making here. But here’s one worth highlighting:

By any objective standard, workplace sexism had been decreasing in America since 1980. But in the early 2010s — years before the MeToo movement — perceptions of sex discrimination among liberal women spiked.

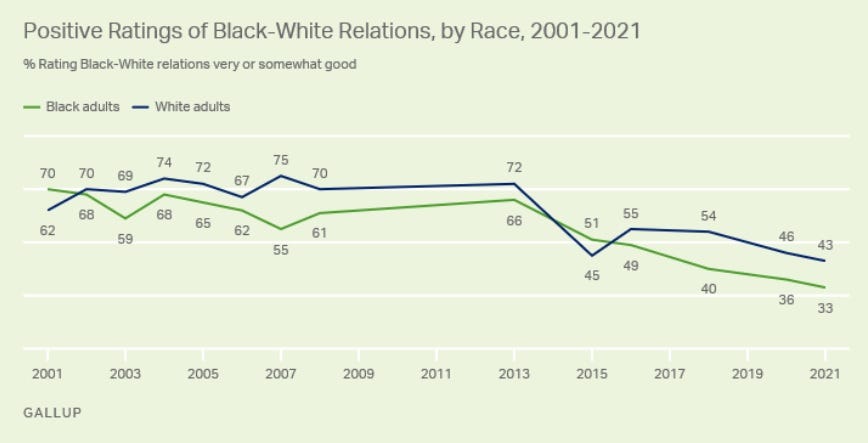

There’s a somewhat similar trend with race relations. Perceptions of race relations had been broadly positive until around 2013, at which point they turned sharply negative:

Unlike many of the other trends, we know why this happened. It wasn’t the election of Obama or the election of Trump — the decline happened in 2014-15. That’s when a bunch of videos of police shooting Black people came out, causing nationwide protests and a general national furor over racism.

The shootings were the proximate cause of the explosion of racial anger in America, but it wouldn’t have been possible without social media. Police shootings and abuses happened plenty of times in America before 2014, and protesters got mad about them. But because people didn’t have the ability to take smartphone videos and broadcast them all over the world at the speed of light, and because apps didn’t give people a social incentive to share those videos and get mad about them, they didn’t have the impact they did until 2014.

Racial tensions are one example where we can easily trace the effect of smartphone-enabled social media on American social divisions. But in general I think you’ll find this same pattern for almost every major cultural issue and every indicator of social division — as soon as Americans got smartphones and social media, we started trusting each other less and getting angrier at each other.

Why? Part of it, certainly, is just the natural tendency of social media — particularly “dunk apps” like Twitter and Bluesky — to elevate the worst people in society and give them a bullhorn to rile up and attack everyone else:

But this doesn’t explain why American society suffered worse than other countries. Perhaps our greater racial diversity created more fault lines for social media to exploit, but this doesn’t explain non-racial fault lines like gender; we have the same balance of men and women as every other country.

I don’t think we know the answer yet. But I do have a hypothesis. I think that more than other nations, America uniquely relied on geographic sorting to deal with its diversity.

In 2008, Bill Bishop wrote a book called The Big Sort: Why the Clustering of Like-Minded Americans is Tearing Us Apart. He showed that liberal and conservative Americans were moving to different cities and different states. Bishop worried that this geographic sorting would create ideological echo chambers, where liberals and conservatives each became more extreme because they only talked to each other.

Perhaps that did happen, but I also suspect that geographic sorting acted as a sort of release valve for the social tensions that built up in the United States after the turbulent 1960s and 1970s. Instead of constantly feuding with their conservative neighbors about abortion or gay marriage or Ronald Reagan, liberals could just move — to San Francisco or New York or L.A. if they had money, or to Oregon or Vermont or Colorado if they didn’t. There, they would never have to talk to anyone who loved Reagan or thought homosexuality was a sin.

Albert Hirschman wrote that everyone has three options to deal with features of their society that they don’t like. You can do nothing and simply endure (“loyalty”), you can fight to change things (“voice”), or you can leave and go somewhere else (“exit”). The ructions of the 60s and 70s were a form of “voice”, but riots and protests and constant arguments about Watergate were no fun. Because Americans had cars and money, many of them could take a more attractive option: exit. In the red-blue America that emerged after the 60s, Blue Americans could move to blue states and blue cities, and Red Americans could do the opposite.

Back in the 1990s and 2000s, this became a cliche. If you complained about politics in your state, people would tell you “Go move to California, hippie!” or “Go move to Texas, redneck!”. It was a joke, but lots of people did exactly that.

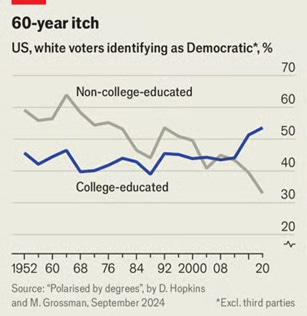

It wasn’t just red states and blue states, either. The sorting was along urban-rural and educational lines as well. As America converted from a manufacturing-intensive economy to one based on knowledge industries like IT, finance, pharma, and entertainment, those industries clustered in “superstar” cities like NYC, SF, L.A., D.C., etc. And at the same time, education polarization was happening in the U.S. — educated Americans were becoming liberals, while less-educated Americans were becoming conservative.

This trend existed in other countries, but not to the same degree. America’s hard pivot to being the world’s research park paid big dividends in terms of GDP, but produced some new social divisions in the bargain.

By the 2010s, if you looked at a detailed electoral map of the U.S., what you saw wasn’t really red states and blue states — it was red countryside and blue cities. The cities were more prosperous than the countryside, which led to the GOP becoming the party of the working class and the Democrats becoming the party of the affluent.

But although we worried about political bubbles, this system seemed to work just fine. A hippie in Oakland and a redneck in the suburbs of Houston both fundamentally felt that they were part of the same unified nation; that nation looked very different to people in each place. Californians thought America was California, and Texans thought America was Texas, and this generally allowed America to function.

In fact, there’s some research showing that bubbles actually reduce polarization. Bail et al. (2018) found that when people are forcibly exposed to opposing views, they become more polarized against those views:

We surveyed a large sample of Democrats and Republicans who visit Twitter at least three times each week about a range of social policy issues. One week later, we randomly assigned respondents to…follow a Twitter bot for 1 month that exposed them to messages from those with opposing political ideologies (e.g., elected officials, opinion leaders, media organizations, and nonprofit groups)…We find that Republicans who followed a liberal Twitter bot became substantially more conservative…Democrats exhibited slight increases in liberal attitudes after following a conservative Twitter bot, although these effects are not statistically significant.

Red America and Blue America became echo chambers that helped to contain America’s rising cultural and social polarization. They helped us live with our ideological diversity, by forgetting — except during presidential elections — that the people who disagreed with us still existed. It was a big country. We could spread out, there was room for everyone. As the man says in Robert Frost’s poem: “Good fences make good neighbors.”

And then that all came crashing down. In the 2010s, everyone got a smartphone, and everyone got social media on that smartphone, and everyone started checking that social media many times a day. Twitter was a dedicated universal chat app where everyone could discuss public affairs with everyone else in one big scrum; for a few years, Facebook structured its main feed so that everyone could see their friends and family posting political links and commentary.

Like some kind of forcible hive mind out of science fiction, social media suddenly threw every American in one small room with every other American.1 Decades of hard work spent running away from each other and creating our ideologically fragmented patchwork of geographies went up in smoke overnight, as geography suddenly ceased to mediate the everyday discussion of politics and culture.

The sudden collapse of geographic sorting in political discussion threw all Americans in the same room with each other — and like the characters in Sartre’s No Exit, they discovered that “Hell is other people.” Conservatives suddenly discovered that a lot of Americans despise Christianity or resent White people over the legacy of discrimination. Liberals suddenly remembered that a lot of their countrymen frown on their lifestyles. Every progressive college kid got to see every piece of right-wing fake news that their grandparents were sharing on Facebook (whereas before, these would have been quietly confined to chain emails). Every conservative in a small town got to see Twitter activists denouncing White people. And so on.

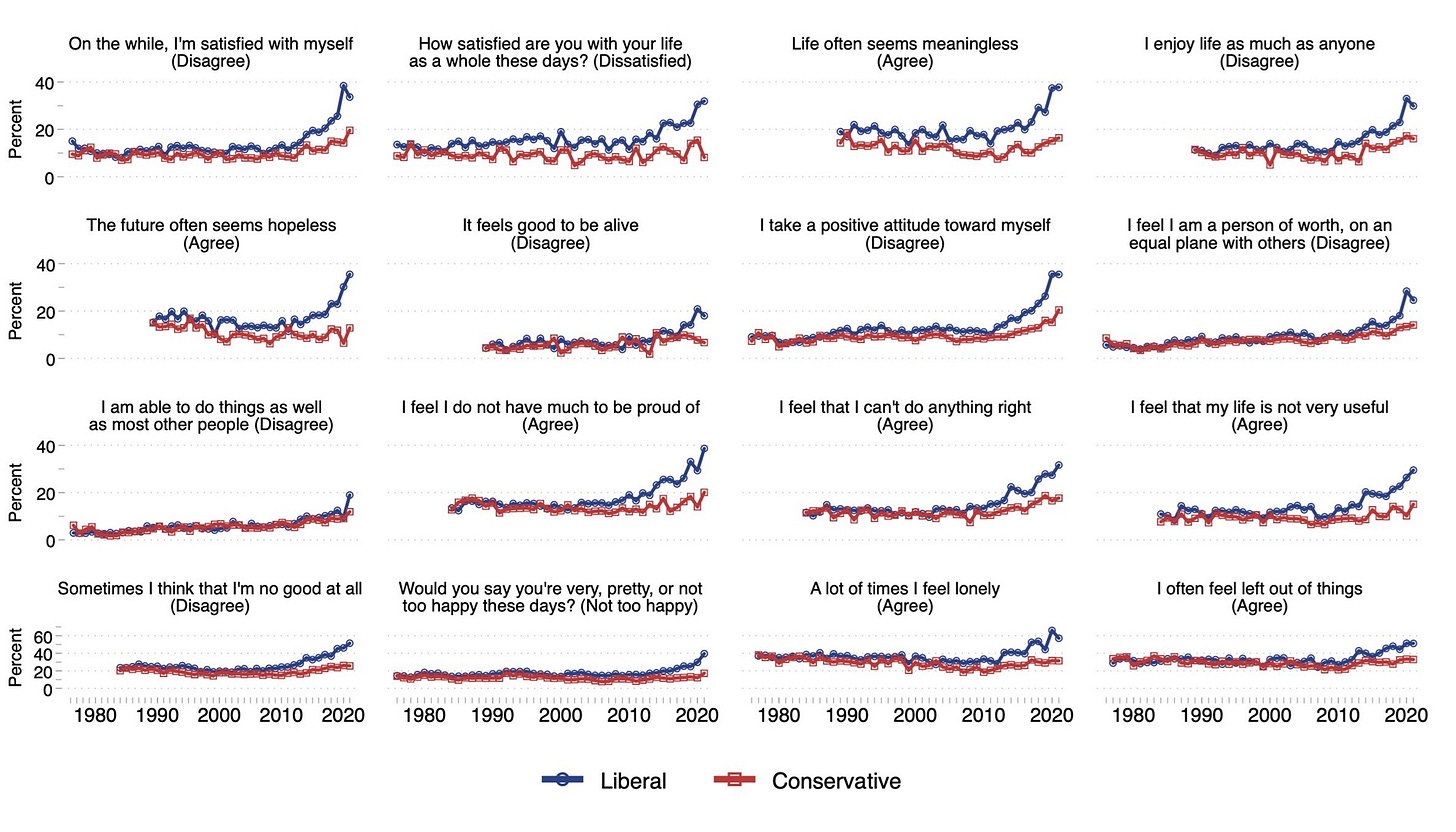

This was hard on everyone, but perhaps it was hardest on educated liberals, who had used the knowledge industry clusters of superstar cities as a lifeline to escape the conservative towns they grew up in. Many liberals became intensely unhappy in the smartphone age:

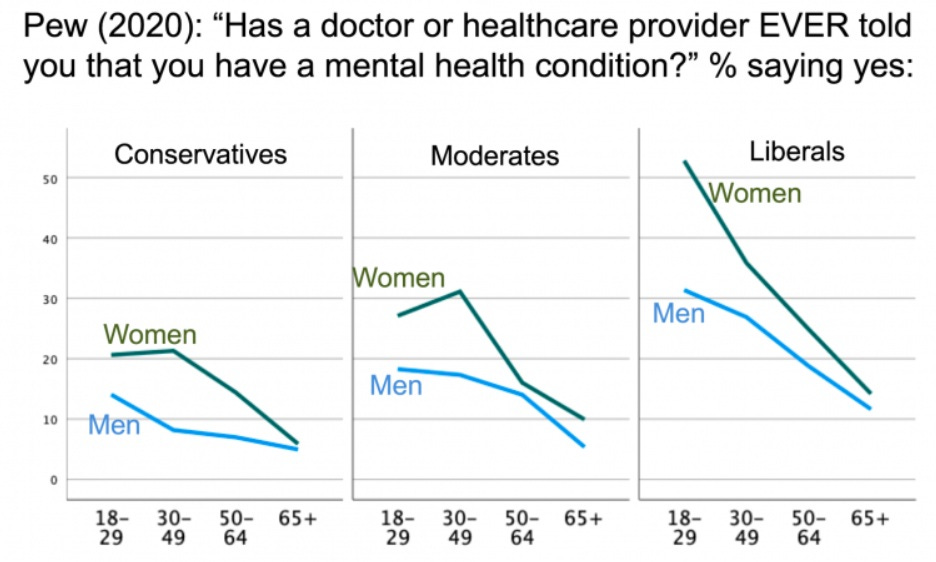

And I think young liberal women in particular bore the brunt:

Social media made exit impossible, and so Americans abruptly went back to voice. Thrown into one small room with each other, they began to complain and fight. And despite Facebook’s turn away from political feeds and Twitter’s fragmentation, Americans still spend much of their waking life online and get most of their political news there.

No physical-world geographic sorting can solve this. People still move to Texas to escape California’s progressive culture, but the people who move are all still on the same apps. Driving immigrants out of the U.S. wouldn’t even remove them from English-language conversational networks; they’d be right there yelling in conservatives’ faces from other countries.

America’s unique strengths were always its size and its freedom; it was a great big country, and everyone could spread out and do their own thing and find their people. Social media collapsed that great big country into a small town — or a handful of small towns — full of busybodies and scolds and disreputable characters and people who disagree with each other’s values. And we haven’t yet learned how to deal with that.

And with foreigners, too. Because English is more or less a universal language, extremists and agitators from every country on the planet are now able to jump into American social media discussions. In fact, a number of prominent political influencers are openly tweeting from foreign lands. But this is dwarfed by the number of foreign people who simply tweet pseudonymously, and whom Americans probably assume are other Americans. This is a problem in and of itself, because it distorts American political discourse; Americans’ idea of “what everyone thinks” is heavily influenced by what foreigners think. That’s fine for dealing with global issues, but it can heavily distort our perceptions of what our fellow countrymen want.

I read this with interest as an Aussie because we have many of the characteristics described as causing the US political polarisation , yet have not had anywhere near the same extent. Australia has huge racial diversity (30% born overseas vs US 14%), we have no end of space and low density of people, we are rich, are mostly knowledge workers. Also have very strong geographic variation in voting, eg country vs city, liberal parts (Melbourne and Canberra), conservative parts (Queensland). So I don’t think Noah’s arguments quite stack up - is there something else unique about the US that has driven the politics?

Could the difference be that Australia has compulsory voting and preferential voting?

I think severe political polarization was explicitly the project of Newt Gingrich and it was the 1994 midterms (and Gingrich's approach to them) that mark the beginning of the politics we are enjoying today