Should we worry about AI's circular deals?

AI companies are borrowing more money to invest more in AI.

A week ago, I wrote a post about the possibility of a bust in the AI sector:

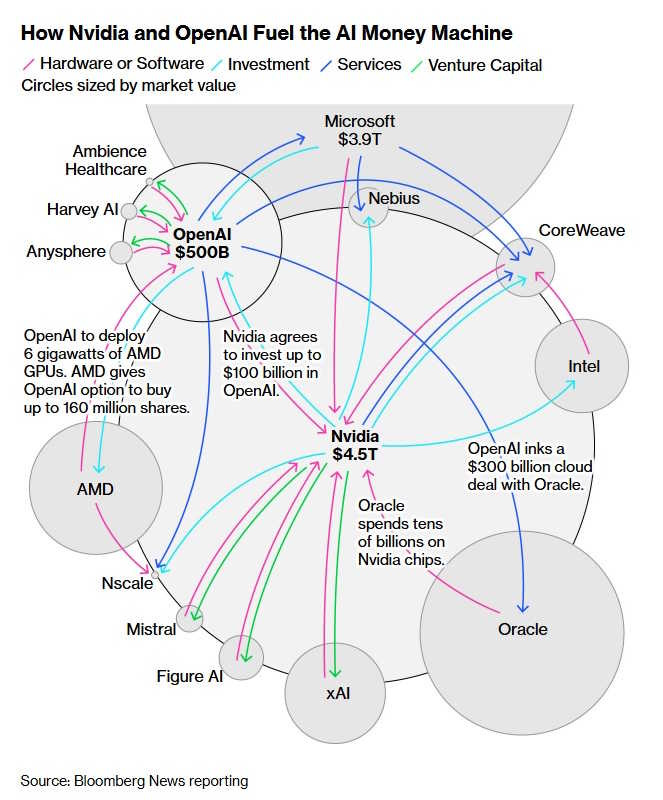

One aspect of the story I didn’t talk about was the web of “circular” deals between AI model makers, compute providers, and chipmakers. Almost every news story or blog post that worries about the threat of an AI bust mentions these. Here are some excerpts from a good overview of the situation by Emily Forgash and Agnee Ghosh in Bloomberg:

Two weeks ago, Nvidia Corp. agreed to invest as much as $100 billion in OpenAI to help the leading AI startup fund a data-center buildout…OpenAI in turn committed to filling those sites with millions of Nvidia chips. The arrangement was promptly criticized for its “circular” nature…This week…OpenAI…inked a partnership with Nvidia rival Advanced Micro Devices Inc. to deploy tens of billions of dollars’ worth of its chips. As part of the tie-up, OpenAI is poised to become one of AMD’s largest shareholders…

OpenAI confirmed it had struck a separate $300 billion deal with Oracle to build out data centers in the US. Oracle, in turn, is spending billions on Nvidia chips for those facilities, sending money back to Nvidia, a company that is emerging as one of OpenAI’s most prominent backers…Nvidia plans to invest up to $2 billion in equity in Elon Musk’s xAI in a financing round tied to Nvidia’s chips…

[Nvidia] agreed to buy $6.3 billion worth of cloud services from CoreWeave, which rents out access to Nvidia chips. OpenAI, meanwhile, received $350 million in equity from CoreWeave ahead of the IPO and recently expanded its cloud deals with the company to as much as $22.4 billion.

And here’s their schematic diagram of the deals:

Here’s a similar article in the Financial Times.

Some people worry that this web of relationships either A) could exacerbate a bust, or B) is a sign that a bust is coming. Here’s an example of the former, from that same Bloomberg article:

[S]ome analysts and academics who’ve tracked the tech industry long enough see uncomfortable similarities to the dot-com bubble. “In the late 1990s, circular deals were often centered on advertising and cross-selling between startups, where companies bought each other’s services to inflate perceived growth,” said Paulo Carvao, a senior fellow at the Harvard Kennedy School who researches AI policy and who worked in tech in the late 1990s. “Today’s AI firms have tangible products and customers, but their spending is still outpacing monetization.”

Paul Krugman, meanwhile, thinks circular deals could be the canary in the coal mine:

Third, there is what Azeem Azhar calls a “financial ouroboros” now taking place in AI: what looks like revenue generated by sales is, in some cases, really just the same stock of money going in circles between the various AI companies…[G]iven the pace at which capacity is expanding, one can’t dismiss concerns that circular flows of money are a warning sign.

So let’s think about why these circular deals could be a problem.

Basically, the supply chain for AI looks like this:

chipmakers —> cloud providers —> AI companies

Chipmakers like Nvidia make chips and sell them to the cloud providers like Microsoft, who operate the data centers that train and run models for the AI companies like OpenAI. OpenAI pays Microsoft for compute, Microsoft pays Nvidia for the hardware to generate that compute. OpenAI is currently trying to cut out the middleman, creating its own cloud computing capacity.

Many of the circular deals take the form of an upstream company buying the stock of a downstream company, who then uses that cash to buy products from the upstream company. For example, Nvidia buys stock in OpenAI, which buys GPUs from Nvidia.1

As far as I can tell, there are two main fears about this sort of deal. The first is that the deals will artificially inflate companies’ revenue, tricking investors into overvaluing their stock or lending them too much money. The second is that the deals increase systemic risk by tying all of the AI companies’ fortunes to each other.

Let’s start with the first of these risks. The question here is whether AI’s circular deals are an example of round-tripping or vendor financing.

Suppose two startups — let’s call them Aegnor and Beleg2 — secretly agree to inflate each other’s revenue. Aegnor buys ad space on Beleg’s website, and Beleg buys ad space on Aegnor’s website. Both companies’ revenues go up. They’re not making any profits, and they’re not generating any cash flows, because the money is just changing hands back and forth. But if investors are looking for companies with “traction”, they might see Aegnor and Beleg’s topline revenue numbers go up. If they fail to dig any deeper, they might give both companies a bunch of investment money that they didn’t earn. This is called “round-tripping”, and it happened occasionally during the dotcom boom.

Now what I just described is completely illegal, because the companies colluded in secret. But you can also have something a little similar happen by accident, in a perfectly legal way. If there are a bunch of startups whose business model is selling to other startups, you can get some of the “round-tripping” effect without any collusion.

On the other hand, it’s perfectly normal and healthy for, say, General Motors to lend its customers the money they use to buy GM cars. In fact, GM has a financing arm specifically to do this. This is called vendor finance. It’s perfectly legal and commonplace, and most people think there’s nothing wrong with it. The transaction being financed — a customer buying a car — is something we know has value. People really do want cars; GM Financial helps them get those cars.

So the question is: Are the AI industry’s circular deals more like round-tripping, or are they more like vendor finance? I’m inclined to say it’s the latter.

First of all, in deals like Nvidia’s relationship with OpenAI, the revenue is only flowing one way. OpenAI pays Nvidia for chips. OpenAI needs chips to perform its core business, which is selling AI services. And Nvidia’s core business is selling chips, especially to people who provide AI services. Both companies are just doing what they’re set up to do.

Second, these are all big companies that come under intense public scrutiny. Nvidia is a public company, with all of the disclosure requirements and accounting regulations that that entails. While it’s possible that foolish investors might look only at Nvidia’s revenue and not its cash flows when deciding to lend the company money or buy its stock, it seems unlikely that it would make a huge difference.

In fact, if you look at Nvidia’s stock price, it doesn’t seem to have risen as a result of the big OpenAI deal — in fact, it’s about the same as it was in August, and showed no visible “pop” after the deal was announced in late September:

This really looks to me more like a case of vendor finance. OpenAI is a big company, but it’s not a public company, which limits its ability to borrow and to sell its stock. Nvidia is a public company, and right now it’s the most valuable company on the planet, with a market cap around 9x that of OpenAI. That makes it a lot easier for Nvidia to borrow money3 — i.e., its cost of capital is lower. It makes a lot of financial sense for Nvidia to use its low cost of capital to support a more capital-constrained customer. As Azeem Ahar puts it:

Customer demand is fierce—and it’s speeding up. Anthropic’s annualized revenue leapt from $1 billion to $5 billion in under six months, a fivefold jump that signals just how hungry enterprises are for AI capabilities; Google confirmed that demand for its AI services nearly tripled between May and October this year, with token consumption surging across every major product line…

How can OpenAI possibly match this blistering pace? Nvidia and the hyperscalers have the strongest balance sheets and can effectively use those to expedite the buildout of capacity.

Now this doesn’t mean deals like this are safe or a good idea — it only means that these deals are unlikely to represent “funny money”.

What about the second risk of circular deals? The more of these deals there are, the more the fate of each of the companies involved depends crucially on what happens to the other companies in the chain. If OpenAI’s business model fails, Nvidia takes two hits — it’ll lose one of its biggest customers, and it’ll also take a big loss on its equity investment.

Nvidia was already making a huge bet on the AI industry. Almost all of Nvidia’s revenue comes from data centers at this point, rather than from gaming or other lines of business — and data centers are almost all about AI now. If there’s a giant AI bust, Nvidia will take a huge hit, whether or not it has to write down its stock in other AI-related companies. Basically, with these deals, Nvidia is making a leveraged4 bet on something that it’s already making an existential bet on.

And Nvidia isn’t alone here. If AI has a big crash, every single company in the circular deal diagram is going to be either toast or in huge trouble, whether or not they have circular deals in place. The fates of all of these companies are already closely tied together, via their mutual dependence on a single technology. Correlations are already very high here. Tying the companies even more closely together with equity purchases doesn’t really change what will happen if AI itself goes bust.

What about counterparty risk? All of these companies are utterly dependent on AI, but that’s different than being dependent on one single other company. Even if AI succeeds wildly, Open AI might fail as a company. So we don’t want Nvidia to become too dependent on OpenAI, because Nvidia’s position as the top AI chip company is too valuable to risk.

This is a real danger. But it’s not clear that the circular deals make things worse — instead, they might be letting AI companies diversify their dependencies. In the first quarter of this year, more than half of Nvidia’s revenue came from just four big mysterious customers — probably Amazon, Microsoft, and Google, and possibly Meta. Building up demand from OpenAI could help Nvidia be less dependent on those big customers.

In fact, I suspect that this is what’s actually going on with these circular deals — diversification. All of these companies are existentially dependent on AI itself, but they don’t want the added vulnerability of being dependent on specific AI companies. So they’re investing in as many of the other big AI companies as they can, in order to diversify away their company-specific risk — just like when you buy a bunch of stocks in order to make your portfolio safer.

Diversification reduces risk. Leverage increases risk. AI companies are (effectively) borrowing money in order to double down on their risky bet on AI itself. But in doing so, they may also get a bit of diversification. We’ll end up with a system that’s more vulnerable to an AI crash, but less vulnerable to the failure of any specific AI company.5

Essentially, I think the story of these circular deals is really no different than the big macro story about the AI boom itself. AI is the most promising technology out there, and we’re simply betting a lot of our economy on the hope that we can exploit its full potential.

Interestingly, some of the deals go in the opposite direction. OpenAI is buying AMD’s stock and AMD’s chips at the same time. The fact that this is characterized as a “circular deal” similar to the Nvidia-OpenAI deal shows that the term “circular” is being thrown around a bit sloppily.

Because apparently every startup is now named after something from the Silmarillion.

Note that even if Nvidia funded its investment in OpenAI out of its own cash, that’s not actually different than borrowing.

It’s leveraged because Nvidia effectively has to borrow to buy the stock of a company like OpenAI.

Of course, they’re all still extremely exposed to Nvidia.

The problem vendor finance is not that this is illegal or shady practice, it's that vendor finance is an indicator that perhaps demand is not as strong as the AI hype would suggest. Why would NVIDIA, which is at the centre of a boom where demand is growing exponentially need to support the purchase of its own products?

The comparison to GM is a false equivalence - GM is in a mature industry where vendor finance is a means of expanding your pool of potential consumers. Of course, vendor finance in a mature industry can and often does push to far, where finance providers sacrifice credit quality to unsustainably promote sales, storing up future losses.

I would also note that NVIDIA is also providing vendor financing slightly less deliberately via its trade receivables which have been growing faster than its revenues and have spiked recently.

To argue that legality is the concern is to argue against a slight misunderstanding of the problem. The reason why this is a bubble indicator is that in a business model as unsustainable as the current AI model (where not a single downstream firm is making a profit), the fact that the poster child of the industry is increasingly depending on vendor financing to support demand for its chips suggests that maybe even at the centre growth may not be quite as high as anticipated. It's important to remember that current valuations are based on continued, unprecedented, parabolic growth, not the kind of growth that vendor financing normally fuels.

If you point to a startup like Uber supporting demand in a similar way at early stage I would argue that Uber was establishing market share in an established industry, whereas NVIDIA is the dominant player in a market which, if it is to grow at the rate valuations depend on, will see unprecedented expansion.

Caveat -- I don't like LLMs. They are clearly derived works of pretty much everything written, and the only reason this wholesale theft is tolerated is financial FOMO, i.e. everyone wants a cut of the loot.

But anyway, the biggest question for investors in AI at this time is whether AI can become a real business, where the fees paid by customers have a chance of covering the expenses of training and operating these models. The expected spend on AI data centers over the next 5 years is about $4-5T, while right now, OpenAI's revenue (not income) is annualized at about $13B, or about 60X lower. Their income, of course, is seriously negative.

This is nothing like GM's financing car purchases. Those purchases will be paid for, plus interest over a fixed small number of years, by customers who believe the cars have real value to them. And GM will make money both from manufacturing the cars and from financing their customers.

In comparison, OpenAI and their ilk don't have *any* customers paying a price that comes close to covering OpenAI's expenses, and they don't even project profitability for the next 4-5 years (1). Seen from that vantage point, Nvidia and AMD are just trying to keep the party going a bit longer, perhaps until their executives can cash out more of their options/RSUs.

(1) -- and that's assuming the AI companies don't eventually have to fork out $$$ to the authors whose works they've incorporated into their models.