Our age of kings

Strongman leaders are trying to bring order to a world disrupted by new media. But the "cure" is worse than the disease.

Here’s a fun little historical analogy: Vladimir Putin as Louis XIV.

Louis XIV, known as the Sun King, was the King of France from 1643 to 1715, making him the longest-ruling monarch in European history. He was the archetypal “absolute monarch” of the 17th century — his famous line was “I am the state.” When you think of a European king, chances are you’re thinking of this guy:

So other than being European rulers with a taste for the grandiose, how is Louis XIV like Putin?

First of all, they both consolidated power after a period of chaos. Putin, of course, arose out of the chaotic 1990s, when Russia’s post-Soviet descent into poverty, civil war, and gangsterism was threatening to collapse the state entirely. Early in his reign, when he was still a child, Louis XIV confronted the Fronde, an uprising of the French nobility against the monarchy. France’s monarchy crushed the Fronde, just as Putin crushed the rebellion in Chechnya.

After putting down their internal rebellions, Putin and Louis XIV established absolutist systems designed to centralize power and prevent future chaos. King Louis sent royal officials called “intendants” to oversee matters in the provinces and report directly to him, reducing the power of the local nobility. Putin dramatically weakened the power of Russia’s local governors and also curtailed the independence of various institutions, creating what he calls a “power vertical” that reports directly to him. The idea of the state as an organization gave way to the idea of the state as a man.

Both leaders also took their countries in a more socially repressive direction — Putin cracked down on gays, activists, and independent media in Russia, while Louis XIV issued an edict banning Protestantism in France. In both cases, this led to an outflow of talent from the country — many Huguenots fled France, while many intellectuals have left Putin’s Russia.

But the most important similarity is the series of wars that the two leaders started. Both Louis and Putin believed that their country’s borders were insecure, and that security required territorial expansion and foreign power projection. In order to accomplish that, both rulers engaged in a series of limited border wars. Louis XIV fought the War of Devolution and the Franco-Dutch War, gaining territory along France’s periphery. Putin fought short, generally successful wars in Georgia, Syria, and Ukraine in 2014.

In the end, however, both Louis XIV and Putin bit off more than they could chew, by scaring their neighbors into checking their advances. Eventually, Louis XIV’s power and military success prompted other European countries to ally against him. Louis ended up facing a powerful European coalition that stalemated him in the Nine Years’ War and again in the War of the Spanish Succession, effectively ending his expansionist dreams.

Putin’s attack on Ukraine in 2022, meanwhile, has united almost all of Europe behind the NATO banner; as the U.S. withdraws from its regional influence, Europe is taking over the defense of its own borders. We don’t yet know the outcome of the Ukraine War, or whether or not Putin’s ambitions will push him to attack other European countries. But right now, the war looks like a quagmire for Russia, especially if the European NATO members keep ramping up defense spending.

Louis XIV is not generally remembered as a brutal tyrant or a rapacious conqueror — in fact, some French people still look back at his rule as a golden age. But his rule had a lot of negative consequences. His intolerance provoked an exodus of human capital. His warmongering exhausted the French treasury and got millions of French people killed, for meager gains of territory and influence. And his absolutism was probably a long-term factor ultimately contributing to the French Revolution, which threw off the entire old regime of which Louis had been the paragon.

Putin probably won’t fare better in the judgement of history, regardless of the outcome of the Ukraine War. Some people will always hearken back to him as the guardian of Russia’s strength and pride, who pulled the country out of the ashes of post-communist dysfunction and won back international respect. But at the same time, a whole lot of Russians are dying, for very little gain of territory, smart people are leaving the country, NATO is stronger than ever, and the Russian economy has been stagnant for years.

So even the paragons of absolute rule in the 17th and 21st centuries weren’t very good rulers. Yet in their day, both Louis XIV and Vladimir Putin spawned plenty of imitators. The style of absolute monarchy pioneered by the Sun King was adopted by leaders like Peter the Great of Russia, Frederick I of Prussia, and Philip V of Spain.

Meanwhile, in the early decades of the 21st century, a lot of leaders are looking eerily like Putin — Recep Tayyip Erdogan in Turkey, Viktor Orban in Hungary, and Benjamin Netanyahu in Israel being classic examples. Xi Jinping’s removal of term limits and personalization of power in China might have been at least partly Putin-inspired, and Donald Trump’s weakening of independent institutions probably drew some inspiration from Putin as well.

In other words, just as 17th century Europe decided it needed absolute monarchs, many of the countries of the 21st century are deciding that they need dictators and quasi-dictators. Why? It’s impossible to say, of course — we don’t really understand the social and political processes that lead certain systems to become popular at certain times. But one prime culprit is the instability created by new media technologies.

Absolute monarchs like Louis XIV arose after more than a century of nearly continuous social and political upheaval in Europe — the Reformation, the Wars of Religion, and the incredibly bloody and ruinous Thirty Years’ War. Those conflicts had many causes, but one of the main ones was the spread of new ideas — mostly religious ideas — enabled by the creation of the printing press. Suddenly, control of information was yanked out of the hands of the Church’s gatekeepers and thrust into the hands of all kinds of intellectuals, activists, and dissidents.

The efflorescence of ideas and communication unleashed by the printing press ultimately helped lead humanity into the age of science and enlightenment. But in the short term — and “short” here meant a hundred years — it caused blood and destruction and chaos and instability. Absolute monarchs were probably one reaction against that instability — elites in countries like France hoped that vesting all power in one capable ruler would enable that ruler to tamp down on the roiling chaos that information technology had unleashed.

The dictators and quasi-dictators of the early 21st century are arguably a similar phenomenon. For the last three or four decades, a series of new media technologies has swept the world, allowing new thinkers and political dissidents to challenge essentially every part of the social order that prevailed before. The spread of Western television was only the beginning. It was quickly followed by the internet, social media, and smartphones.

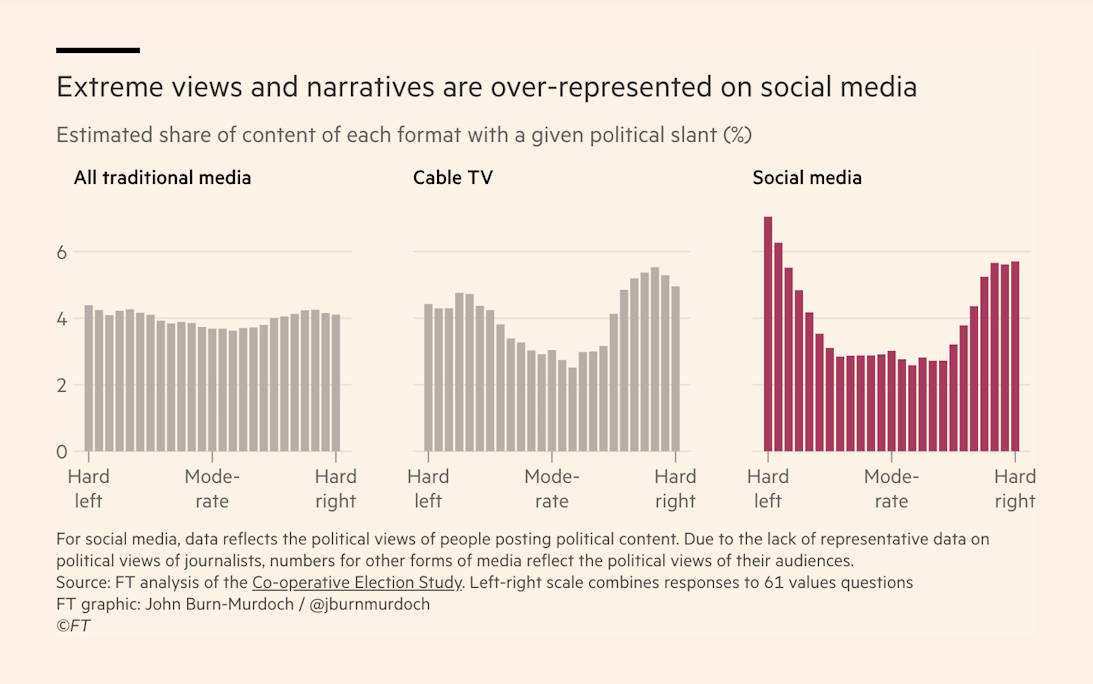

This explosion of new information technologies, like the printing press half a millennium earlier, blew away all the old gatekeepers. Some people still celebrate this as a victory for marginalized voices, but an increasing number of people realize that it’s a major factor behind the rise of extremism and illiberalism. Social media broadcasts extreme viewpoints at the expense of the moderates whom the old gatekeepers used to elevate:

Thomas B. Edsall even goes so far as to say that the smartphone — which enables social media to become a constant, enveloping presence — is the death knell for Western democracy.

Vladimir Putin’s rise was not a reaction to social media (which didn’t really exist yet), and the internet probably played only a minor part. But some of the leaders that are now following in Putin’s footsteps are reacting to a wave of unrest that swept the world in 2019 and 2020:

I continue to think, for example, that Trump’s return to power in 2024 was a delayed reaction to the George Floyd protests of 2020, and to the ideology that grew up around the Black Lives Matter protests since 2014. Xi Jinping’s increasing authoritarianism may have been motivated in part by the Hong Kong protests of 2019. These protest waves, like most of the others around the world, were both inspired by ideas spread over social media, and organized directly via social media as well.1

Our new printing press led to new Wars of Religion. And just as before, some countries are responding by imbuing national leaders with dictatorial or quasi-dictatorial powers, hoping they’ll tamp down the fire of popular unrest.2

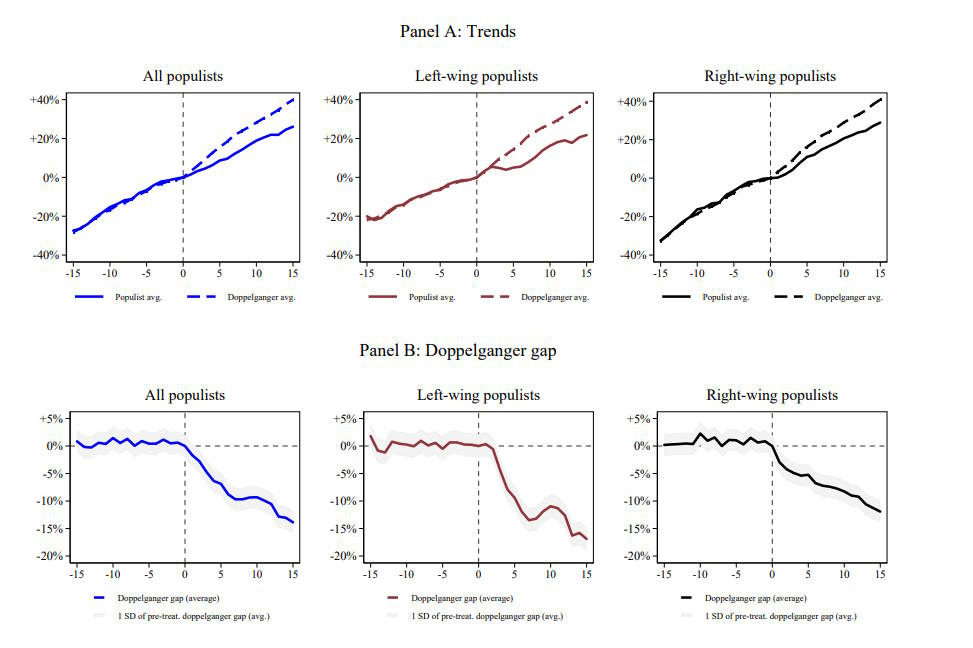

This is, to put it mildly, not ideal. First of all, Putin-type leaders tend not to be very effective. Even discounting their tendency to start (and lose) wars, the economic impact of populist leaders is typically very negative. Here’s a chart of what happens to GDP when populists get elected:

But in the long run, the cost of absolute monarchy may be even greater political instability and violence. The UK and the Netherlands, which evolved into constitutional monarchies even as their neighbors were embracing absolute monarchs, ended up becoming stable democracies. France and Russia, on the other hand, fared much worse, with revolutions that were incredibly violent and bloody and led to further wars.

Trump, Xi, and Putin are all old men in their 70s. After they’re gone, the dictatorial and quasi-dictatorial systems they put in place will remain, but without the charisma and finesse that allowed the populists to finesse the contradictions of their regimes. People will get mad and strain against the new shackles that the absolute rulers put around their wrists. I predict that the new age of kings won’t last.

For a good book on this, read Martin Gurri’s Revolt of the Public.

There are, of course, some big differences I’m glossing over. In the 17th century it was mostly nobles and other elites who thought installing an absolute monarch would quash unrest; in the 21st century, the Putin-like rulers almost all rose to power as populists, winning elections and only later crushing democratic institutions.

One small quibble: Xi did not crack down on Hong Kong because there was unrest there. Xi introduced massive changes to the Hong Kong system and the people reacted with unrest.

Ever since ‘the kingship descended from Heaven’ in ancient Sumer. strongmen (an a few women) leaders have been turning their powers to self-aggrandizement and the accumulation of wealth and power, suppression of political opposition, and territorial expansion through various means of economic, social, and military aggression. It is one of the oldest stories in what we call ‘civilization’.

The United States was created as an alternative to four millennia of top down rule, some of it relatively benign, some unimaginably cruel, most somewhere in between, but but all based on some variation of either ‘the divine right of kings’ or ‘our political, financial, and/or military success entitles us to make all the decisions for everybody else’.

Our alternative (Novus Ordo Seclorum) has been stumbling along for nearly 250 years, and across the world that alternative has been a beacon to many who have attempted, with varying degrees of success to emulate it, and it remains, as one of the best of us once noted, “the last best hope of earth”.

We are just under three weeks away from the anniversary of Lincoln’s extraordinary reiteration of that alternative on a cold November day at the site of the greatest battle ever fought on the American continent - coincidentally (or perhaps not) just days after the public debut of Ken Burn’s documentary on the American Revolution.

The fact that the 250th anniversary of our alternative will be overseen by a President who has no concept of what we were founded to become, nor any concern to maintain this, the most extraordinary, the most crucial, the riskiest, and the most complex ongoing experiment in human society and government ever attempted, is perhaps, one of the greatest ironies in our history.