I remember a time back in 2017, when I was at a friend’s dinner party. He mentioned that one of the other guests was a housing activist, and that because I was also interested in housing issues, she and I should talk. The activist asked me what I thought we needed to do to ensure affordable housing in San Francisco, to which I responded “We should let people build a lot more of it.” At which point a look of shock and dismay came over her face, and in a horrified voice she asked: “Market rate??”

“Yes,” I said. “Market rate.”

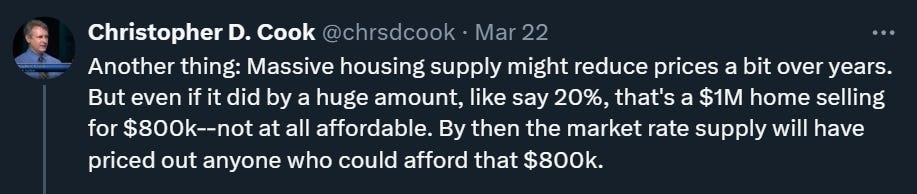

In fact, the belief that building market-rate housing raises rents is surprisingly common. For example, independent journalist Christopher Cook recently tweeted:

And Calvin Welch of 48Hills declares:

By definition an affordable housing crisis cannot be solved by the market for the simple reason that the folks needing the housing are simply priced out of the market.

The logic behind these posts isn’t immediately clear. For example, Cook seems to be concerned mainly with the price of buying a house. But “affordable housing” policies, like inclusionary zoning, rent control, and public housing, are all about renting houses (unless you’re in Singapore, but we’ll talk about that later). When Cook calls for “affordable housing projects” and “supportive housing for homeless people”, he’s talking about rental units. Those projects will do nothing to bring down the $800k home purchase price he complains about.

As for Welch, it’s not clear what sort of “definition” he thinks he’s referencing here. I don’t want to put words into his mouth, but it seems as if he thinks that the price of a market-rate rental unit comes built into its walls and floors — that market rents in an expensive city are fixed, and have nothing to do with the number of units that exist there.

Whatever the reasoning here, though, what clearly comes through is a deep-seated antipathy toward market-rate housing — the same antipathy that I encountered at my friend’s dinner party. This antipathy is misplaced. Though building market-rate housing won’t always be enough to solve a city’s housing problems all by itself, it’s an important part of any affordable housing policy.

How market-rate housing makes cities more affordable

Cities like San Francisco and NYC have various policies to make housing more affordable. One example is rent control. Another is inclusionary zoning, which mandates that the people who own a rental property offer some percent of the units for a discount. These are all types of price controls.

Because some units in a modern American city are price-controlled, it means that market-rate units will usually be more expensive than the average unit. This isn’t always 100% true — some market-rate units might be even cheaper than price-controlled units because they’re really small and crappy, or because they’re in a really dangerous neighborhood, etc. But in general, market-rate units will be more expensive than the average unit.

So it’s easy to see how building more market-rate housing can increase average rents. The key word here is “average”. Think about a city where everyone owns a Honda Civic, which sells for $26,000. And then you build a Lamborghini and offer it for sale in that city for $300,000. Maybe some rich person ditches their Civic for the Lambo, or maybe some rich person moves into the city and buys the Lambo. Either way, the average price of cars in the city has gone up, since now there’s an expensive Lamborghini in the average.

But did building the Lambo make cars in the city less affordable? No, it didn’t! A Civic still costs $26,000. There are still the same number of Civics, so everyone can still get a $26,000 Civic if they want one. No one is being forced to pay more for a car than they were before the Lambo was built. The rise in the average price of a car is purely a statistical quirk.

In fact, the arrival of the Lambo will probably make cars more affordable in this city. If one rich person ditches their Civic to buy the Lambo, that means there’s one more Civic on the market in this town. Suppose the town starts with 10,000 people, each with a Civic. Then after the richest person puts their Civic on the market, you now have 9,999 people and 10,000 Civics. That means the price of a Civic will go down — whoever’s selling that extra Civic will have to offer it at below $26,000, to get someone to buy it as their second car. That price cut will lower the average price of Civics in this town.

Ta da! Building an expensive car made cars in general more affordable.

This is exactly how building market-rate housing — even fancy “luxury” market-rate housing — makes housing more affordable in general. Suppose you bulldoze a parking lot in San Francisco and build a gleaming new tower full of market-rate apartments targeted at tech workers. Maybe some tech workers move in from San Jose or Palo Alto to live in those apartments — but probably not, since their jobs are down in San Jose and Palo Alto. More likely, they move into the gleaming new market-rate units from other parts of San Francisco. They move from low-rises in the Mission and Bernal Heights, from old Victorians in the Haight, and so on.

And when the tech workers move to the new tower, what happens to those rental units they just vacated? Those units go on the market! And unless landlords want to let their units sit vacant for many months (which costs them a lot of money), they have to rent those units at a discount to whatever they were charging before.

Who moves into those newly discounted units? Maybe some other tech yuppies looking for a bargain. Maybe some service workers paying market rent in the East Bay and commuting over every day to work in SF. Maybe some middle-class family currently paying market rent elsewhere in SF. It’s not clear.

But whoever it is, the availability of a discounted market-rate unit gives them some negotiating leverage with their current landlord. They can now say “Oh hey, landlord. That discounted market-rate unit just opened up across town and I’m thinking about moving there. But I’ll stay here if you cut my rent a little bit.” Their current landlord now has an incentive to cut their rent a little bit, in order to avoid having their unit go vacant.

So by this process, building fancy new expensive market-rate housing lowers rents for regular folks.

This process is especially important when you have a city that’s attracting a big influence of highly-paid people looking for rental units (i.e., yuppies). Without any new market-rate construction, the yuppies will flood into the city’s older housing stock, offering to throw wads of cash at landlords for the chance to move into a low-rise or an old SF Victorian or a Brooklyn brownstone or whatever. By building gleaming new towers of fancy “luxury” units, you can divert those yuppies, so that they don’t start a bidding war with existing middle-class residents for existing middle-class units.

I explained this in one of my favorite old posts, in which I called the towers “yuppie fishtanks”:

Now, there is an important exception to this. If you bulldoze existing housing in order to build new market-rate housing, you can accidentally raise rents. This can happen if:

you bulldoze price-controlled housing and replace it with market-rate housing, or

you bulldoze low-quality market-rate housing and replace it with nicer market-rate housing

In the first of these cases, you’re raising rents by removing a price control. In the second case, you’re raising rents by raising the quality of housing. And in both cases, you’re destroying some existing supply, which reduces the benefits of building new market-rate supply.

This is why it’s optimal to build market-rate housing in place of things like warehouses or parking lots, if you can. And this is why it’s especially cynical and counterproductive when so-called “progressives” in cities like SF block the construction of new housing on parking lots, as happens rather regularly.

But even if you have to tear down existing housing to build market-rate housing, you can get a net benefit in terms of affordability. If you tear down 50 units of low-rise housing and replace them with 500 units in a huge tower, that’s a lot of new supply. So the benefit can outweigh the cost in terms of affordability.

Of course, there is a way that building market-rate housing can raise rents within a small area. It’s called “induced demand”. If a new apartment tower makes a neighborhood seem nicer or more upscale, it can draw in high-income people from elsewhere, raising demand for housing in the nearby area. That increased demand will raise rents locally. But it’ll still improve affordability overall, because the rich people who move to that neighborhood will leave their old neighborhood. That reduces demand for housing in the old neighborhood, which will make it more affordable.

In fact, when we look at the data, induced demand doesn’t seem to be that big a deal — a new apartment tower usually doesn’t gentrify a neighborhood. But even if it does, you need to consider the effect on affordability of other neighborhoods as well. And here, the same old logic applies — building market-rate housing puts downward pressure on rents throughout the metro area.

The evidence is in favor of market-rate housing

So far, I’ve been speaking in terms of theory. Let’s talk about some evidence.

There’s plenty of academic research showing that market-rate housing construction makes cities more affordable, through exactly the mechanism that I described above. I’ve written several posts about this before (here’s one, here’s another, here’s yet another), but it’s good to reiterate.

Let’s start with a 2023 paper by Evan Mast in which he tracks where people move from and where they move to, and comes to exactly the same conclusion:

I illustrate how new market-rate construction loosens the market for lower-quality housing through a series of moves. First, I use address history data to identify 52,000 residents of new multifamily buildings in large cities, their previous address, the current residents of those addresses, and so on for six rounds. The sequence quickly reaches units in below-median income neighborhoods…Constructing a new market-rate building that houses 100 people ultimately leads 45 to 70 people to move out of below-median income neighborhoods, with most of the effect occurring within three years. These results suggest that the migration ripple effects of new housing will affect a wide spectrum of neighborhoods and loosen the low-income housing market. (emphasis mine)

This is exactly the process that I described in the previous section. One neighborhood builds new market-rate housing, and higher-income renters move there from other neighborhoods. That frees up units in the other neighborhoods, which lowers rent for lower-income renters.

And here’s a 2023 paper by Bratu et al. that finds the exact same thing:

We study the city-wide effects of new, centrally-located market-rate housing supply [in] the Helsinki Metropolitan Area. The supply of new market rate units triggers moving chains that quickly reach middle- and low-income neighborhoods and individuals. Thus, new market-rate construction loosens the housing market in middle- and low-income areas even in the short run. Market-rate supply is likely to improve affordability outside the sub-markets where new construction occurs and to benefit low-income people.

Now let’s look at a 2023 literature review by Vicki Been, Ingrid Gould Ellen, and Katherine M. O’Regan. This is from their abstract:

[R]igorous recent studies demonstrate that…Increases in housing supply slow the growth in rents in the region…In some circumstances, new construction also reduces rents or rent growth in the surrounding area…The chains of moves sparked by new construction free up apartments that are then rented (or retained) by households across the income spectrum[.]

And here is an excerpt from the paper:

Using different methods to overcome endogeneity, a few new studies confirm that new supply moderates rent increases for the city as a whole…Greenaway-McGrevy …studied the effects of an unusually large scale upzoning of Auckland, New Zealand…[S]ix years after the policy was fully implemented, rents for three bedroom dwellings in Auckland were between 26 and 33 percent less than [similar neighborhoods in other cities]…Similarly, Mense…found that a “1 percent increase in yearly new housing supply causes the average rent level [in the local municipality] to fall by 0.2 percent.” Further, he finds that new market-rate housing reduces the housing cost burden for all renters in the municipality, not just those renting at the high end of the market.

This is exactly what we’d expect to see from the pattern I’ve been describing — new market-rate housing frees up units in other neighborhoods and makes the city as a whole more affordable. Here are ungated versions of Mense’s paper and Greenaway-McGrevy’s paper, if you want to read those. Phillips et al. have another good roundup of research on the topic.

So market-rate housing increases affordability citywide. As for the idea that new market-rate housing makes the small local area less affordable — the “induced demand” or “gentrification” effect — there are a bunch of papers showing that even that doesn’t usually happen. Check out Li (2019), Mast (2019), Dragan et al. (2020), Pennington (2021), or the other papers listed in Been et al.’s literature review. New market-rate housing lowers rents in the surrounding area a little bit, though the effect is probably mitigated by the induced demand effect. In a few cases, induced demand can even cancel out the supply effect within a very small radius. At the citywide level, though, you get the full effect.

Opponents of market-rate housing will occasionally grasp at a single study that seems to go against this growing weight of evidence. But even then, they almost always misunderstand the research they try to cite. For example, Calvin Welch cites a study about “filtration” (price changes for the same housing unit over time), which he thinks supports his argument:

The Yimby argument is that filtering works only in one direction, down. As thousands of new market-rate units are created in ever more dense developments, the Yimbys argue, “over time” existing housing, as it ages, will become more affordable as wealthy folks move out into the new, market rate units.

Newsom and Breed parrot that line and transform it into government policy, arguing that approving dense, market-rate housing development will, over time, lower housing costs.

Facts revealed in the study show that filtering rates also increase. Instead of going down in San Francisco (and five other California cities) they go up, by about 0.7 percent every year. Producing more market rate units will, overtime, continually increase housing costs, not lower them. It’s simply how the market works, says the researchers at Freddie Mac, in high income markets like San Francisco. And that has been the San Francisco experience.

The “study” Welch refers to is Liu et al. (2020), a paper by three economists at Freddie Mac. The paper finds that in some locations like San Francisco, aging units are rented by higher- and higher-income renters, even as they deteriorate in quality.

And WHY do old, crappy apartments get rented by richer people even as they become older and crappier? Liu et al. investigate why, and here’s what they find:

Markets with high levels of regulatory restrictions on new construction tend to have upward filtering. Conversely, markets with lower regulatory restrictions on new construction tend to have faster than average downward filtering rates. We also look at differences in filtering across housing supply elasticities that incorporates regulatory and available land constraints using the estimates of housing supply elasticity derived by Saiz (2010)…In our sample, MSAs with elastic housing supply have faster downward filtering than the national average, whereas markets with inelastic housing supply have upward filtering, on average.

In other words, when a city like San Francisco refuses to build new market-rate housing, yuppies move into older housing — the old Victorians in the Haight, the low-rises in the Mission, etc. — and price the middle-class people out of those units! It’s exactly what I described in the last section of this post.

This study, which Welch tries to use as evidence against market-rate housing construction, in fact explicitly supports market-rate housing construction as a way of making cities more affordable. Just like all the other studies I cited.

The antipathy towards market-rate housing is so strong that it drives people to grasp at straws, even when the straws turn out not to exist.

Market-rate housing isn’t always enough

Now, I should mention that just because market-rate housing is useful for making a city affordable, that doesn’t mean it’s sufficient. Sometimes a city experiences such a huge influx of high-earning workers — like the tech boom in San Francisco in the 2010s — that even a big program of market-rate housing construction in that city alone won’t be enough to stop rents from rising. This is why you need to build more market-rate housing at the state level, so you get the maximum downward pressure on rents. But even that might not be enough, because people generally live where they work, and if a bunch of high-salary tech jobs move to San Francisco, building cheap housing in the suburbs can only accomplish so much.

That’s why in addition to market-rate housing, it helps to build public housing. Singapore is the best at this — they build a ton of new condos (called “HDBs”) and then sell (well, “lease”, but really sell) those units cheaply to the populace. If American state governments, or even the federal government, copied this strategy, we could build a lot more housing that’s affordable by design. (This is much more effective than inclusionary zoning, which tends to do very little to increase affordability, and can hurt supply). The YIMBY movement has been pushing for public housing in California; this push has been unsuccessful so far, but hopefully it’ll succeed soon.

But even though building market-rate housing isn’t always the only thing you need to do, you do need to do it! Opponents of market-rate housing construction have a ridiculous fantasy that if they can just restrict supply enough, rich yuppies will be forced to move far away, while middle-class and working-class people will get to stay where they are. This is simply not what happens. What actually happens is that money finds a way — the landlords together find a way to get what they want, which is to expel the middle-class and working-class renters out of town, and have the higher-paying yuppies take over their units.

This is exactly what happened in San Francisco. Incredibly low rates of market-rate housing construction in SF and surrounding cities led to soaring rents and a stagnant population, while median incomes also soared — not because everyone in SF got a giant raise, but because lower-income people were driven out of the city by high rents!

People need to abandon the fantasy that blocking market-rate housing can drive rich people out of town. It cannot. All it can do is to make life more unaffordable for everyone.

Yes, your city needs to build more market-rate housing in order to become more affordable. So build more of it.

I'm surprised that anyone needs this explained to them, but thanks for doing so.

I worked in housing affordability for years and the one thing I wish people understood is that there is no such thing as "affordable housing" affordability is the conflux of the unique properties of the home, the income of the purchaser and the urban land market. So many people think there are "luxury" homes made for rich people and "affordable" homes for regular people. But house prices haven't risen because developers suddenly started building exclusively rich people housing for no reason. Land prices are the key to making housing affordable for regular people again, and that means upzoning and a lot of building.