It's OK not to be fat

Instead of moral problems, let's think of things like obesity as technological problems.

“O God, give us the serenity to accept what cannot be changed, the courage to change what can be changed, and the wisdom to know the one from the other.” — Winnifred Wygal

“Put the fork down!” — Denis Leary

I was going to write about the Elon-Trump blowup, but some things are just too ridiculous and extremely-online even for me, so I’ll skip it for now — at least until it starts seeming like it might have some economic ramifications. Instead I think I’ll write about something more optimistic, because my blog has admittedly been a little bit of a downer of late.

Over the past year, I lost about 45 pounds — about 20% of my maximum body weight. This didn’t seem like a particularly epic weight loss journey — certainly a lot less than the 70 pounds that Matt Yglesias lost a few years back. And unlike Matt, I didn’t have bariatric surgery to shrink my stomach. In fact, I didn’t even use Ozempic, Mounjaro, or any other weight-loss drug at all. All I did was eat less and exercise a little bit more. This seems like the kind of boring, everyday story that doesn’t really merit a blog post. But I think the way that I lost weight actually does have some interesting implications for how, as a society, we should think about weight loss — and about other personal struggles like addiction.

My not-so-epic weight loss journey

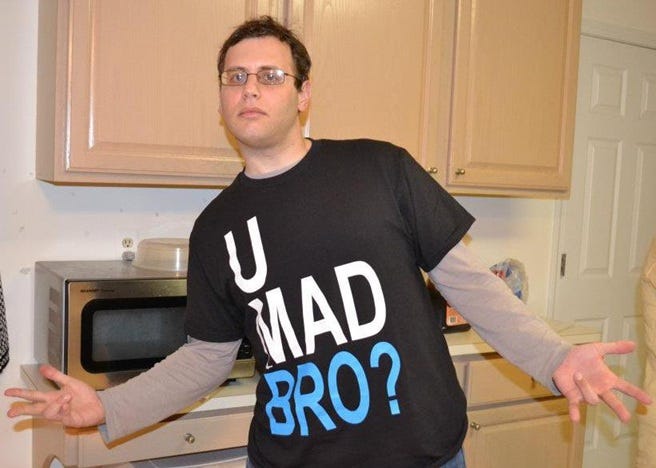

First, here’s the story. For most of my life, I haven’t been a fat guy — sometimes I would get a bit overweight, but I’d lose the weight after a year or so. This is what I looked like in grad school, at age 30:

But in 2020-22, I got much fatter than I had ever been in my life. My weight peaked at around 235 or 240 pounds. Part of this was from inactivity and overeating during the pandemic, but most of it was from migraines.

In mid-2021, for unknown reasons (maybe Covid?), I got chronic vestibular migraine. This wasn’t the painful kind of migraine, thankfully. But it meant that I was pretty much constantly dizzy, and felt like my head was stuffed full of rags. This was one reason I left Bloomberg and became a full-time blogger in late 2021; I couldn’t handle more than 4 hours of screen time per day, so I had to give up either my hobby or my job, and I chose to give up my job.

Anyway, one thing that triggered my near-constant migraines to get even worse was any drop in blood sugar. So I minimized the dizziness by constantly eating. As you might expect, this caused me to gain quite a lot of weight over two years’ time. For the first time in my life, I became obese.

Eventually the migraines got a lot less bad, and I decided it was time to lose the weight I had put on. I considered taking Ozempic or another weight-loss drug, but I decided to see how easy it would be to just lose the weight by eating less. Over the next year, I started paying attention to how much I ate. If it was “time to eat”, but I wasn’t hungry, I wouldn’t eat anything. And when I did eat, as soon as I felt like I wasn’t hungry anymore, I would stop eating. Basically, this is what a lot of Japanese people do in order to avoid becoming overweight.

That was the main thing I did. There were also a few other smaller things. I generally ate less dessert and sugary stuff, though I still ate some. I exercised more — mostly aerobic exercise. And I also ate less salt. This last one wasn’t actually for weight loss — I also had high diastolic blood pressure, so my doctor told me to cut down on salt. But I found that when I ate less salt, I got less hungry — possibly because I’d retain less water, which meant my stomach would shrink. (I drink a LOT of water, so I never got dehydrated.) Finally, I invented some dishes that tasted great without having much salt or sugar in them.

But the main thing was just only eating enough to stop feeling hungry. At first, this meant that I ate only a little bit less than usual. But as time went on, I noticed myself eating less and less each day, until eventually my food intake leveled out at maybe half of what it used to be. My assumption is that this was because my stomach was shrinking.

I am not an expert in weight loss. I have only a fairly shallow understanding of metabolism, the actions of macronutrients, and why certain diets lead to weight loss. But one thing I’m pretty sure of is that having a smaller stomach makes you want to eat less. The reason is because bariatric surgery, which makes people’s stomach smaller, is an incredibly effective technique for long-term weight loss. This is what Matt Yglesias used, and it’s what my friend (and occasional guest blogger) Armand Domalewski used. When I hang out with Armand, I always marvel at how quickly he gets full. He has a small stomach because of the surgery. There must be some kind of sensory feedback from your stomach to your brain, so that when your stomach gets full you stop feeling like you want to eat.

That was my guess, anyway. I figured that as long as it was working, I didn’t need to look too deeply into the mechanism — that would just “nerd-snipe” me and tempt me to overly complicate things.1

And it did work, so I kept doing it. I’ve never really eaten breakfast; now I found myself eating only a very small lunch, or occasionally no lunch at all. Strangely, I had plenty of energy throughout the day — in fact, more energy than before I started dieting. If I exercised I’d start to feel hungry, and then I’d eat something until the hunger stopped, just like always.

This strategy didn’t lead to me losing weight at a spectacular pace — it was just about 5 lbs per month. Weight loss drugs or more severe diets can let you lose weight much faster than that. But I didn’t want to stress out my liver, or develop loose hanging skin, etc. 5 lbs a month was plenty for me, and over 9 months or so, I had lost pretty much all of the weight I put on from both the migraines and the pandemic combined. I should still lose about 15 pounds, which I think I’ll do now that I’m pretty sure I don’t have loose skin from the earlier weight loss.2 I don’t expect it to be very difficult.

Self-control is about attention, not “willpower”

So what’s interesting about this story? It seems pretty boring; I ate less, I lost weight. Wow, who knew? But I realized, as I was doing it, that the difference between losing weight and not losing weight was just attention.

When I didn’t pay attention, I didn’t lose weight, because I kept eating after the point where I was no longer hungry. When I paid attention, I was able to control when I stopped eating.

Most people think that if you lose weight without the aid of drugs or surgery, it takes “willpower”. But what is willpower? I know there’s a whole huge psychology literature on the concept, and within that literature is some evidence that people have some sort of “reserve”, at least in the short term, that gets depleted when they try to endure pain or stay focused on a task. But when it comes to eating less, I find it more useful to think in terms of two distinct willpower-related concepts: pain tolerance, and attention.

Pain tolerance is being able to endure distress and discomfort. A lot of people think that this is what weight loss requires. After all, eating less makes you hungry, and hunger is painful and unpleasant. So a lot of people think that losing weight requires you to be hungry a lot, and to endure that pain.

For a lot of people, I think this introduces a moral dimension, or at least a self-worth dimension, into how they think about weight loss. They think that to succeed in losing weight requires toughness and strong motivation — you have to be tough enough to fight through constant hunger, and motivated enough to want weight loss even more than food.

This idea of weight loss as a personal test raises the stakes, because it’s not just your waistline that’s on the line, but your whole sense of self-worth. If you fail to lose weight at first, or if you hit a plateau and gain a few pounds back, the “willpower” model says that this means you’re a wimp, or that you just didn’t want it enough. This makes weight loss a terrifying prospect for people are scared of discovering that they just don’t have what it takes, and a source of anguish and despair for people who suffer even temporary setbacks.3

Except that’s just not how it went for me. I didn’t endure much pain at all. While losing weight, I was rarely hungry — maybe a little bit, for a short amount of time, but when I felt hungry I’d always go eat something. And because my strategy was to eat until I no longer felt hungry, whatever small hunger pangs had driven me to eat would be quelled.

Instead, attention was the key to my strategy. I realized that in the past, the times when I had gained weight — for example, when I was writing my dissertation — are when my attention was wholly occupied by something other than personal health. Whereas all I had to do in order to lose weight was focus on it.

I think this is a much emotionally healthier way to think about weight loss. A lot of people who can’t lose weight simply don’t have the time and energy to devote to it. I was lucky, because being a self-employed blogger gave me the flexible schedule I needed to give weight loss my full attention. But you can’t be expected to make weight-loss another part-time job, on top of the job you already have!

So instead, you should consider doing what humanity always does when we’re faced with constraints on our time and our labor: automate the task.

Technology solves this

In general, I think technological solutions to human problems are severely underrated. Progressive writers love to declare that “tech won’t save us”, and decry the vile techbros who think a magic venture-funded gadget can overcome the eternal foibles of human nature. Instead, what most writers think we need are social solutions — we need to restructure our institutions, our politics, our mores, and our culture in order to balance out, or perhaps to better accommodate, our timeless flaws.

This approach has occasional successes, but in general I think it fails. In the Covid pandemic, for example, social solutions — social distancing, lockdowns, universal masking — weren’t valueless, but they ended up being a lot less important than vaccines, Paxlovid, dexamethasone, and other technological solutions. Society failed us, and tech saved us.

With regards to the problem of weight loss, the social approach has been especially ineffective. Decades of awareness campaigns, education, social shaming, and public health failed to stop the obesity rate from climbing and climbing. Eventually, in despair, the social-solutionists turned to “fat acceptance” instead — they accepted that most people were going to be fat as an immutable fact of biology, and so our only hope was to just feel good about that. Victoria’s Secret put chubby lingerie models in its ad campaigns.

I have no moral or aesthetic problem with fat acceptance — in fact, I think shaming fat people is pointless, because effective weight loss usually doesn’t come from shame. But I think that fat acceptance is generally bad for society, because obesity is very, very unhealthy. We shouldn’t accept poor health if there’s something we can do about it.

And now there is something we can do about it! Over the past few years, researchers discovered that semaglutide, a diabetes drug that had been in use for a long time and which goes by the names of Ozempic and Wegovy, was extremely useful in getting people to lose weight. Although there may be some more complex mechanisms, the simplest way the drug works is simply by suppressing your appetite.

Usually you’d have to worry about the long-term side effects of a drug like that, but Ozempic has been in widespread use since 2017, and it doesn’t seem too bad. Maybe some negative side effects will appear after 30 years; we’ll see.

Anyway, everyone realized that Ozempic makes people lose weight, so they started developing even more effective drugs in the same category, like tirzepatide (Mounjaro/Zepbound) and retatrutide (not approved yet). Of course we know a lot less about the long-term side effects of these newer drugs. But even just Ozempic itself has completely changed the game when it comes to weight loss.

In fact, although some people worry that they’ll have to be on Ozempic for life or else the fat will come right back the minute they stop, the evidence shows otherwise. Most Ozempic users keep the fat off or even continue to lose more weight after they stop the drug, and fewer than one out of five gain it all back:

It really looks like technological solutions have succeeded where social solutions failed. As Scott Alexander likes to say, “society is fixed, biology is mutable”. The U.S. obesity rate, which had climbed relentlessly year after year, has finally turned around and started to fall, and mass adoption of Ozempic and similar drugs is the prime suspect for why:

If the side effects of these drugs continue to be minimal and the weight loss they cause continues to be permanent, then we’ve found a technological solution to obesity.4

For some people, this seems like cheating. People who spent years believing that weight loss was a personal mountain to climb are now a bit deflated to find that you can just take a helicopter to the summit. People who viewed weight loss as a test of their self-worth may now feel melancholy that someone else came and made it easy. Thin people who felt special for their thinness may feel a bit devalued and commoditized. And people who relished the chance to shame the fatties of the world for being weak and irresolute will simply have to find someone else to feel superior to.

This, I think, shows the limitations of viewing fat as a moral or self-worth issue. During my own weight loss, I found out that it was just a matter of cost — of time and attention. And since time immemorial, human beings have been dealing with costs by automating them away. We don’t view washing clothes as a test of our self-worth; we just stick them in the washing machine and hit a button.

Similarly, there’s no reason we should have to spend the time and effort paying attention to everything we eat, and whether or not each bite makes us stop feeling hungry. We have more productive things to do with our time. If weight loss is just about labor, then Ozempic and the other drugs are simply labor-saving devices like washing machines.

And of course, there are some people for whom my own weight loss solution can't even work — people who have some sort of metabolic problem or other physical condition that makes “just eat less” not an option. For many of those folks, the new drugs are a godsend.

The history of technology is one of dispensing with old challenges so we can focus on newer, more interesting ones. There’s no reason clever creatures like us need to spend huge chunks of our precious lives figuring out how not to be fat. Just use a tool, press a button, get the job done, and move on to something more worthy of your talents. If I ever have to lose a substantial amount of weight again, I definitely will.

But just for fun, let’s ask ChatGPT o3 why having a smaller stomach makes you feel full more quickly. ChatGPT says:

Short answer:

Because a smaller‐capacity stomach reaches its “stretch limit” with less food, it trips the body’s mechanical and hormonal satiety circuits sooner. Those circuits tell your brain “meal over” long before the larger stomach would have sent the same signal.

How the normal-sized stomach signals fullness

Step 1. Food enters and stretches the stomach wall…Smooth muscle in the fundus and body of the stomach expands…2. Stretch-sensitive nerve endings fire…Vagal afferent mechanoreceptors embedded in the gastric wall detect tension…3. Signals reach the brainstem (NTS) and hypothalamus…The nucleus tractus solitarius integrates “fullness” information with taste, smell, and metabolic cues…4. Gut hormones reinforce the message…5. Conscious perception of satiation…You feel comfortably full and stop eating.—

Why a smaller stomach reaches that stop-signal faster

Lower volume → same wall tension at a smaller meal size

Think of two balloons: one partly pre-inflated (large stomach) and one nearly empty (small stomach). Add 300 ml of water. The small balloon hits its stretch limit first, firing mechanoreceptors earlier. pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov

Compliance often drops too

Bariatric sleeve or banding surgeries remove the most distensible portion of the fundus. The remaining sleeve is stiffer, so pressure rises steeply with even small food boluses. pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.govcmcoem.info

Rapid transit to the intestine boosts “backup” fullness cues

With less reservoir space, food spills into the duodenum quickly, stretching the small-intestine wall and further amplifying vagal signals (“phantom satiation”). pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.govucsf.edu

Hormonal profile shifts

After capacity-reducing surgery, circulating GLP-1 and PYY rise markedly and ghrelin often falls, so the brain receives both mechanical and chemical “stop eating” messages. sciencedirect.com

Neural adaptation works in reverse

Overeating can desensitize gastric stretch receptors; shrinking meal size for weeks re-sensitizes them, so fullness arrives sooner even without surgery. mdpi.com

Everyday implications

Portion control really can “teach” your stomach. Consistently smaller meals reduce gastric accommodation over time, so you feel full on less.

Liquids vs. solids: Liquids exit the stomach quickly, so they stretch it less; after surgery, patients are advised to avoid calorie-dense liquids that can bypass stretch signaling.

Pacing matters: Eating slowly lets early stretch and hormone cues register before you’ve overshot.

Not just capacity: Anxiety, sleep, and even gut microbiota can modulate these same satiety circuits, which is why fullness is partly psychological and metabolic, not purely mechanical.

Bottom line

A smaller or less compliant stomach hits the “distension threshold” with fewer bites, and a cascade of vagal and hormonal signals makes you feel full faster—an elegant bit of gut–brain engineering that bariatric surgeons (and portion-control dieters) deliberately exploit.

I had read that 40-50 pounds was the upper limit of how much weight you could lose without developing loose skin.

I also think this leads to excessively costly dieting strategies, like starving yourself every other day, or restricting your diet to foods that make you feel full without giving you a lot of calories. You don’t have to live like that!

In fact, Ozempic and the others may have a bunch of health benefits on top of beating obesity. Scott Alexander had a great rundown last year.

Great post, glad you're healthier now.

100% agree on the stomach stretching thing. But I would add we have TWO fullness systems in our body. The stomach stretching one is the fast/short term one (that tells us to STOP eating).

The other one is from fiber in our colon. A healthy microbiome releases short chain fatty acids SCFAs when it digests soluble fiber (mostly from veggies, beans and fruits). When the colon has less fiber in it, it releases less SCFAs. When your brain is getting SCFAs, they make you feel contented and not hungry. This slow/long term process tells you when its time to go find more food. The START eating signal.

Bariatric surgery spoofs the first pathway. Ozempic spoofs the second pathway.

The low fiber diet in the US (processed and fast foods are mostly zero fiber) means the second pathway is telling many Americans its 'time to eat' all the time. Ozempic turns that signal down/off.

Or you can just eat 20+ grams of soluble fiber a day, by eating plenty of veggies, beans and fruit.

I'm guessing that your diet contains a decent amount of whole foods and fiber, that is why you didn't 'need' ozempic. If you were eating more processed junk, your outcome might have been different.

Hi Noah,

Thank you for sharing your weight loss story! I'm sincerely happy for you.

You make a great point about willpower consisting of attention and pain resistance. As a counterpoint to your story, I want to share a bit about my weight loss attempts, which were very, very different from yours. (I'm a woman, so that probably makes a big difference because of lower BMR.)

I would absolutely freaking *love* my weight loss to be as easy as, "Pay attention = eat less = lose weight without ever feeling hungry." That's just not how my body works.

When I eat until I'm not hungry anymore, I maintain my current (excessive) weight. When I try to cut back "just a bit," it's the worst of both worlds: I'm hungry enough for it to be annoying, but my caloric intake is still high enough that any weight loss is too slow to be noticeable. It's extremely demoralizing and I give up.

The only times I actually succeeded in losing weight was when I was extremely strict about imposing eating limits. None of that namby-pamby feel-good "listen to your body" stuff, because my body clearly wants to be fat. No, it was "this is how much you're having for lunch, body, and if you don't like it too effing bad."

And it sucked absolute ass.

I would sit at my desk, trying to focus on the grant I was writing or the experiments I was planning, and all the time there would be a dialogue in my head:

"I'm hungry."

"You had lunch an hour ago."

"Yeah, but it wasn't enough and I'M FREAKING HUNGRY!"

"Quiet down. Snack is in two hours, you know this. You just have to last till then."

"But I'M HUNGRY NOW!!!!!"

And on and on like this, pretty much around the clock. You can imagine what it did for both my mood and my productivity. I couldn't just make those thoughts stop; they came unbidden. I could only resist them.

To make it extra fun, if I didn't eat enough I would get what I called a "hypoglycemic headache" - a really bad, unpleasant headache that made me useless for anything except menial tasks (no focusing on intellectual work with a hypoglycemic headache). Weight loss, for me, was surfing the very thin line between "hungry enough to lose weight at an appreciable rate" and "not so hungry that I trigger a hypoglycemic headache" (I learned to read the early warning signs).

So, Noah, I applaud your accomplishment and also ask you to recognize that you were extraordinarily lucky in how easy weight loss turned out for you, judging by your description.