Is U.S. industrial policy learning from its mistakes?

I hope so, because mistakes are being made.

When FDR was running for office in 1932, determined to quash the Great Depression, he promised a policy of “bold, persistent experimentation”. He didn’t really know how to fight a depression — no one really did, because in previous times, fighting depressions and recessions hadn’t been something the government did. FDR just promised to keep trying things until he found what worked.

And that’s exactly what he did. Many of the New Deal policies were missteps, or even debacles — the attempt to create government-sanctioned monopolies in order to raise corporate profits, the attempt to create artificial scarcity in the agriculture industry to boost farm incomes, and so on. To his credit, FDR eventually abandoned most of the approaches that didn’t work. What ultimately remained of the New Deal economic approach after Roosevelt’s death contained only a few pieces of his initial approach; instead, it was mostly made up of more successful ideas that had been discovered along the way, like financial regulation, Social Security, unemployment benefits, and large-scale infrastructure projects.

Similarly, America’s ultimately successful war production effort in World War 2 involved a lot of early missteps, both in the private sector and the public sector. At first, production of things like merchant ships and bombers was painfully slow, but as America’s businesses learned how to speed things up, and as bureaucrats learned how to properly support those businesses, efficiency improved by orders of magnitude and the U.S. became the Arsenal of Democracy.

These are two very important examples of a very important principle: New economic approaches need to iterate, actively learning from their mistakes and making course corrections.

You could argue that the U.S. has been doing something similar in the present day, with the shift to industrial policy. At this point, my sense is that most American policymakers and intellectuals recognize — or at least, they believe — that it’s important to revitalize U.S. manufacturing. But as to how to do that, no one really knows.

The Trump administration believed they could spark a manufacturing renaissance through presidential exhortation, tariffs, and corporate tax cuts. They failed; nothing of the sort was accomplished. The Biden administration kept the tariffs and tax cuts, but added another major weapon: government subsidies. The IRA, the CHIPS Act, and some other bills as well promise to pay companies to build factories in the U.S., and they promise to pay consumers to buy the things those factories produce.

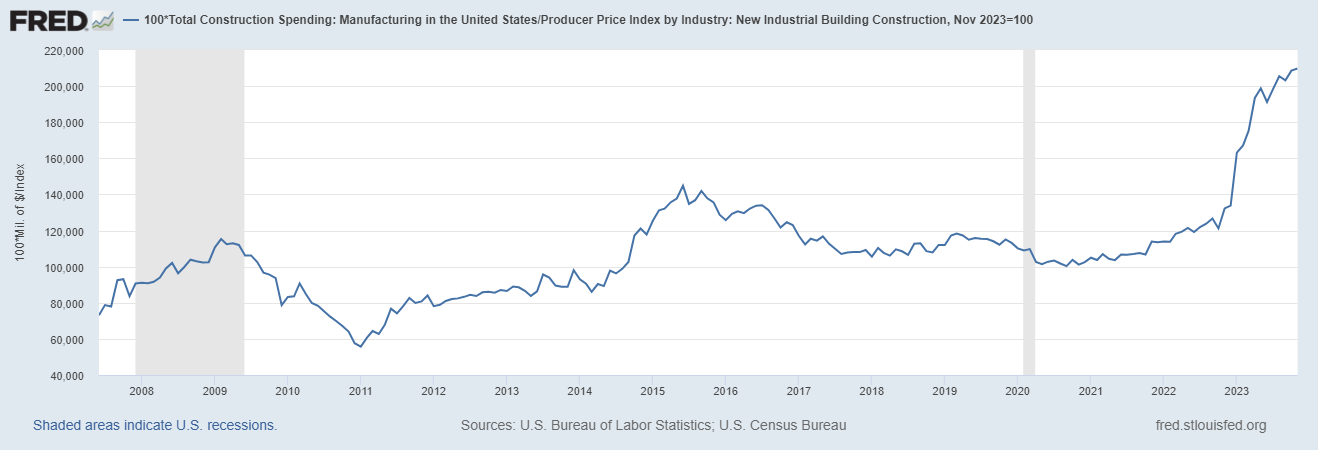

So far, this has achieved mixed success. The Biden years have seen an explosion of spending on factory construction, the like of which hasn’t been seen in many years.

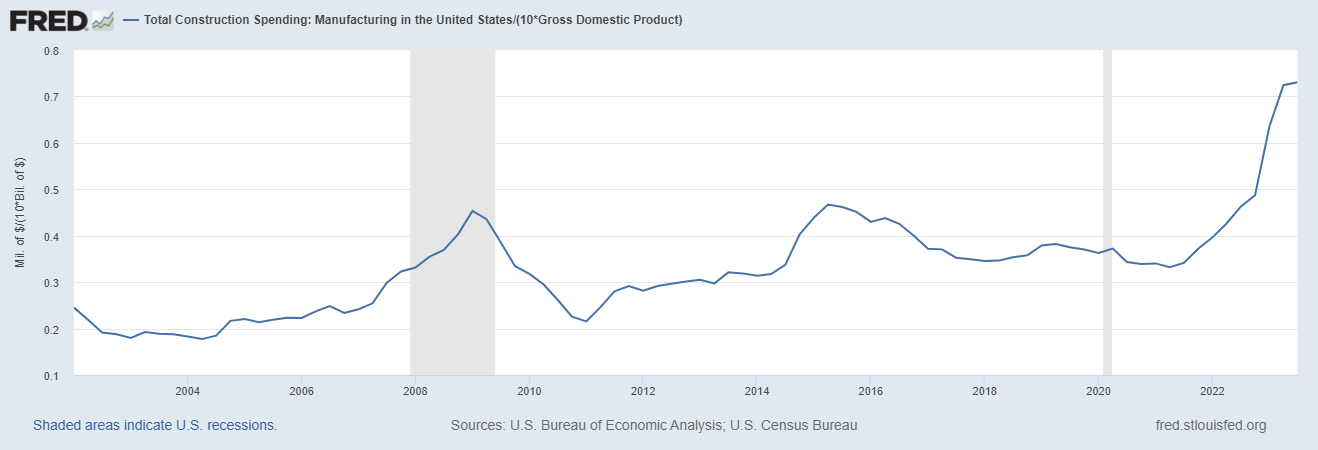

Here’s manufacturing construction spending as a percent of GDP, which goes back a few more years. You can see that the Biden factory boom has been like nothing we’ve seen this century, and certainly bigger than anything under Trump.

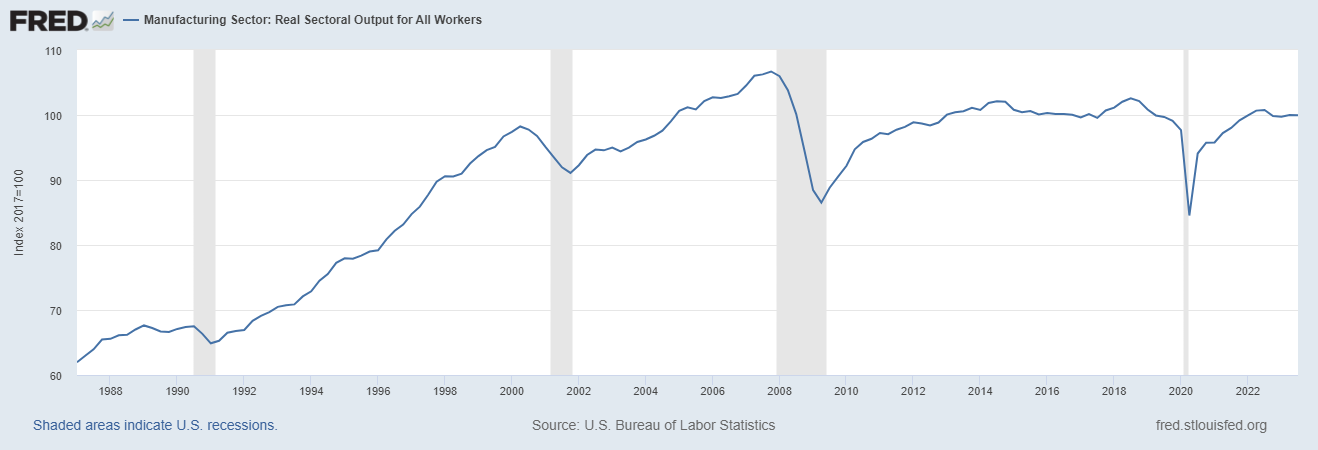

Score one for bold, persistent experimentation, right? Well, maybe. Actual manufacturing output hasn’t risen at all. It remains at the same level it’s been stuck at for a quarter of a century:

And in fact, the manufacturing sector now looks like it might even be in a bit of a slump.

There are basically three possibilities here. One is that factory construction takes a long time, and eventually the factories that are being built today will start pumping out actual batteries and computer chips and solar panels and cars, and at that point manufacturing output will rise. I think this is the likeliest possibility.

It’s also possible that the factory construction spending data, and/or the price index that I’m using to adjust for the actual cost of building factories, is compromised in some way, and factory construction spending isn’t really happening much at all yet. I think this is a pretty unlikely possibility, but worth tracking down.

But there’s also a third, scary possibility — it’s possible that money is getting spent, but only on overpriced consultants and environmental impact studies and other things that are mostly waste, and that the actual physical factories won’t get built. In a post last year, I argued that Americans have become used to the idea that reallocating dollars on spreadsheets means that real stuff is getting built, but that this is often not the case. I called this mistaken belief “checkism” — the idea that all you have to do is write the checks, and everything else will work itself out.

So while I’m happy about soaring factory construction spending, I’m only tentatively, guardedly happy. Factory construction is just one necessary first step. It isn’t really over until computer chips and batteries and cars and solar panels rolling out of the U.S. factory gates in large numbers. And even then it’s not really over, since that production has to be sustained.

But in fact, there’s a danger even beyond checkism. There’s also the danger that U.S. state capacity is so low that the government checks won’t even go out at all, because the government won’t know where to send them.

This appears to be happening with EV chargers. In 2021, the bipartisan Investment Infrastructure and Jobs Act allocated $7.5 billion of government money for building EV chargers throughout America. But here’s what Politico reported in December:

Congress at the urging of the Biden administration agreed in 2021 to spend $7.5 billion to build tens of thousands of electric vehicle chargers across the country, aiming to appease anxious drivers while tackling climate change.

Two years later, the program has yet to install a single charger.

States and the charger industry blame the delays mostly on the labyrinth of new contracting and performance requirements they have to navigate to receive federal funds. While federal officials have authorized more than $2 billion of the funds to be sent to states, fewer than half of states have even started to take bids from contractors to build the chargers — let alone begin construction…

There are two obvious hypotheses about what’s slowing things down: 1) lack of bureaucratic state capacity, and 2) onerous contracting requirements.

The Politico article mentions the lack of state capacity as a problem. The U.S. government simply doesn’t know how to approve companies to receive subsidies, and doesn’t have the personnel to do it:

Jim McDonnell, director of engineering at the American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials, which is assisting states in administering the federal charger funding, said the work of distributing the NEVI funds largely fell to state offices that had never worked on EV charging before.

A recent article in the Wall Street Journal, meanwhile, details some of the problems with contracting requirements:

The FHWA issued a rule requiring that workers for most projects be certified by the electricians union, or another government-approved training program…Florida’s Transportation Department said projects were stifled by guidance that stations be 50 miles apart. Pennsylvania lamented restrictions on building stations with fewer than four charging ports…

The latest funding comes with rules that will make sure charging station customers are even scarcer than workers. Half of the grant money is set aside for “disadvantaged communities that are marginalized by underinvestment,” which by the agency’s description includes Alaskan and Arizonan Indian tribes and urban parks and libraries. The other $312 million is allocated among the places with high usage, such as a charging station in the university town of Durham, N.C.

Now, this doesn’t mean that EV chargers aren’t getting built. They are! It’s just the private sector building them, not the government.

Perhaps this isn’t so bad; if the private sector can build chargers but the government can’t, at least chargers are still getting built. And while the private sector builds, the government can observe its own failure to build, and can observe where the choke points are.

But when private construction is dependent on government subsidies, it’s a problem if the government can’t get those subsidies out the door. This appears to be happening with the CHIPS Act and its semiconductor subsidies. This is from an article from Tom’s Hardware in December:

The U.S. Department of Commerce announced its first semiconductor manufacturing incentive as part of the CHIPS and Science Act this week. BAE Systems, which makes various chips for applications such as fighter planes, is set to get $35 million from the U.S. government. U.S. Commerce Secretary Gina Raimondo said that she expects to announce a dozen funding awards over the course of next year. Meanwhile, she warned that some fab projects could still be delayed.

One $35 million grant is a tiny, tiny percent of the tens of billions of dollars allocated to chipmaking subsidies in the CHIPS act. It’s a rounding error. And it’s already been a year and a half since the act was passed!

CNBC had some more details on the delays last summer. Private companies are spending on factory construction in the expectation that government subsidies will eventually arrive and make it worth their while. But the subsidies haven’t arrived yet:

The potential for federal funding has spurred some potential huge investments in the semiconductor sector. In total, $231 billion has been announced in private sector semiconductor investments in the United States, according to the White House. But many of those projects are contingent on receiving federal government aid…

As companies await the federal dollars, many larger semiconductor firms have opened their coffers to begin expansion. Intel, Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co. and silicon carbide producer Wolfspeed have all hired workers and started construction despite not receiving any federal CHIPS Act funding.

What’s holding up the disbursal of government subsidies? The two prime culprits are the same as with the EV chargers. Perhaps bureaucratic state capacity is low, so the government can’t handle all the applications and allocations. CNBC reported last summer that 140 people had been hired to evaluate CHIPS Act subsidy applications; perhaps many more are needed, and perhaps they need time to gain experience.

The other main possibility is that projects are being saddled with unrealistic politically driven requirements in order to receive subsidies — what Ezra Klein calls the “everything bagel” of progressive red tape. The Bloomberg Opinion editorial board made this argument a year ago:

Companies hoping for significant Chips Act funding must comply with an array of new government rules and pointed suggestions, meant to advantage labor unions, favored demographics, “empowered community partners” and the like. They should also be prepared to offer “community investment,” employee “wraparound services,” access to “affordable, accessible, reliable and high-quality child care,” and much else. One can debate the merits of any of these objectives. But larding already-uncompetitive businesses with crippling new costs to advance completely unrelated social goals is simply at odds with the stated purpose of this law.

Whatever it is, the government needs to figure it out and do whatever it takes to fix it. If chipmakers don’t get their subsidies, the credibility of the administration and the U.S. government and the very idea of industrial policy will suffer tremendously. Companies will simply believe that future industrial policies are false promises. And the current round of factory construction could end in half-finished or idled factories if subsidies that they depended on to be profitable never end up arriving.

In fact, this is already starting to happen. Samsung, which is building a gigantic new $17 billion chip fab in Texas, recently delayed the project until 2025. Permitting issues were one problem the company cited, but the other was the U.S. government’s delay in disbursing subsidies. Business Korea reports:

A key issue is the delay in the disbursement of U.S. government subsidies. The U.S. government had promised a total of US$52.7 billion in subsidies to companies building semiconductor plants locally as part of the CHIPS Act. However, reports emerged last month about a potential advance payment of up to US$4 billion in subsidies to Intel by the Biden administration, raising concerns about possible prioritization of domestic companies over Samsung Electronics in subsidy allocation and timing.

Sensing this atmosphere, Samsung Electronics’ U.S. branch also conducted events urging U.S. politicians to expedite the subsidy process. They emphasized that “Samsung’s semiconductor investments over the past 30 years total US$47 billion. Samsung’s decision to invest ahead of the CHIPS Act decision was based on trust in the U.S. Congress and administration,” urging timely subsidy disbursement.

This is a pretty inexcusable failure on the part of the Biden administration. It’s not as if the administration doesn’t know that Samsung will be getting CHIPS Act subsidies for this fab! So why waste years going through the motions of approving the application? Just mail the checks!

And even if the government manages to disburse subsidies, industrial policy will then have to deal with another huge barrier: America’s utterly broken environmental review process. Even if the checks get written, the factories still need to get built. And Gina Raimondo, Biden’s Commerce Secretary, is very worried that this could add more years of delay:

Commerce Secretary Gina Raimondo warned that US efforts to build out the domestic semiconductor industry could be delayed by years if companies are required to go through standard environmental reviews…Projects under construction by Micron Technology Inc., Intel Corp. and Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co. — who’ve together pledged up to $195 billion in US investment — are among those that could be affected by lengthy reviews that Raimondo and a bipartisan group of lawmakers had tried to avoid…

Raimondo in October urged Congress to approve a measure exempting federally-funded chips projects from such environmental permitting, which she said could force construction to stop for “up to years.” Asked whether that was still her assessment after House Republicans killed the exemption measure last week, she said “yes, potentially.”…

[T]he vast majority of [CHIPS Act] projects that win funding will now go through permitting under the National Environmental Policy Act…That review could force a lengthy construction stoppage at sites key to the US effort.

Note the politically salient detail here that Republicans killed the permitting exemption in this case. In general it’s progressives who defend NEPA as a key part of the progressive coalition. Bipartisan agreement that NIMBYs should be able to delay semiconductor factories for years, by suing them on flimsy environmental pretexts, would be very bad news for U.S. industrial policy.

NEPA isn’t the only environmental permitting requirement; the full list is long and onerous. But NEPA is the worst, because it allows any local NIMBY to sue to make companies do years of pointless paperwork, even if they already meet every environmental requirement.

Now, here’s a key fact: NEPA only applies to projects that receive federal government money. What that means is that industrial policy is uniquely burdened by environmental review laws. If a company chooses to forgo all government subsidies and build a fab or battery factory or charging station on its own, NEPA isn’t required. The U.S. government’s own supposedly progressive permitting policy is therefore biasing the economy away from industrial policy and toward the private sector having to do everything on its own.

In other words, U.S. industrial policy is running into at least three big sets of problems:

Lack of bureaucratic state capacity

Onerous contracting requirements

Permitting, especially NEPA

The optimistic scenario is that we’ll learn from these failures. The U.S. government can observe these bottlenecks and figure out ways around each one. I argued in a post back in April that the fact that industrial policy can help expose inefficiencies in our policies is one of its biggest potential strengths:

But there’s no certainty that the mistakes will get fixed; the government has to be bold and persistent, just like FDR and the New Dealers were. Biden is certainly upset that his signature accomplishments won’t bear fruit by election night, but it’s not clear that the sense of urgency has reached a critical point yet. The hard thing about learning from failures is that you have to want to learn. And I’m not yet sure how badly America’s industrialists want to learn.

In addition to the three problems, it may may be a knowledge problem. The players simply don't have the technical and managerial capability. And don't know it!

Very good overview, thanks.

The CHIPS act and the infrastructure bill make some sense and could easily have passed years ago except Pelosi controlled the House and wouldn’t allow it under Trump. The CHIPs act was a bipartisan effort started in Congress during the Trump years but had very little to do with either Trump or Biden (a rare example of a good concept actually backed by key players from both parties in congress). I think it is largely a waste of money in normal times (as the plants being built in the US by TSMC aren’t for their most advanced chips) and the idea of the US fabricating even more commoditized chips flies in the face of comparative advantage. However, it does make sense from a national security point of view, as do some of the limitations on sales to China.

The IRA seems to be a boondoggle that is less industrial policy and more paying off donors. I think this leads to a gross misallocation of resources as using some of your “best” skilled labor and mechanical engineers, construction engineers to assemble largely Chinese parts using Chinese IP in old tech (lithium batteries) doesn’t seem to be the optimal use of these scarce resources. I know the IRA is about more than EVs, but a lot of it about EVs. Time will tell. As you note, early days yet.

Manufacturing has effectively been in a recession over the past year, but I believe much of this is a hangover from subsidized overconsumption of real goods during Covid, particularly 2021-2022. I believe this is cyclical rather than an implicit criticism of the effectiveness of recent donor handouts. We should hopefully see a bit of rebound this year and next. Maybe not in autos as at these interest rates fewer people can afford car loans.