In which I rebut Nate Silver on the economy and Matt Yglesias on nuclear

Bloggers love to argue.

We bloggers love nothing more than a good argument. In the overall political discourse and in the minds of many readers, I am often grouped with Matt Yglesias and Nate Silver. Indeed, I think both of them do excellent work, and we often agree on things. Which is why it’s especially fun when I get a chance to argue with those guys about something! Arguing with your friends over technical points is a welcome distraction from screaming about the upcoming presidential election, threats to democracy, hurricanes, FEMA disinformation, accusations of pet-eating, Vladimir Putin, and so on.

Recently, both Matt and Nate have disagreed with stuff that I wrote (or at least, I think Nate disagreed), so I am taking a break from election-season screeching to issue some wonky rebuttals.

Matt Yglesias is (slightly) wrong on nuclear

As Matt has noted, he and I often write similar posts making similar arguments at similar times. So in order to help combat the rumor that we are both robots operated by the same shadowy AI superintelligence,1 Matt has attempted to disagree with me about something. And that thing is nuclear power.

I wrote a post a couple of weeks ago saying that although nuclear will be a niche source of electrical power in the future — maybe 15-20% of electricity generation — it won’t be the dominant form of electricity, because other stuff (solar and batteries) has just gotten better for most applications:

Matt writes that although we agree on most of this issue, I underrate nuclear power’s future importance:

In fact, almost all of what Matt writes is stuff I agree with. Opponents of nuclear are almost always very wrongheaded, and are surprisingly powerful in progressive circles. The symbolism of supporting nuclear power is important, because it prioritizes the abundance mindset, and science, over the politicized degrowth agenda that has infected parts of the environmental movement.

But in the part where Matt actually disagrees with me, he makes a mistake. He argues that nuclear is important to supplement solar power in the winter, when the sun is weaker:

That said, there’s an important difference between the marginal cost of adding solar and the average cost of creating an all-solar system, because (drumroll) the sun is sometimes not shining…Noah’s counter is that improved batteries have made intermittency problems less severe, which is true. But that’s mostly intermittency on the scale of day versus night, not summer versus winter. Current batteries aren’t great at long-term storage. This is exacerbated by the fact that right now, electricity demand peaks in the summer when people use air conditioning (which matches the sunshine), but in the net zero future, we’re all supposed to be relying on heat pumps during the winter.

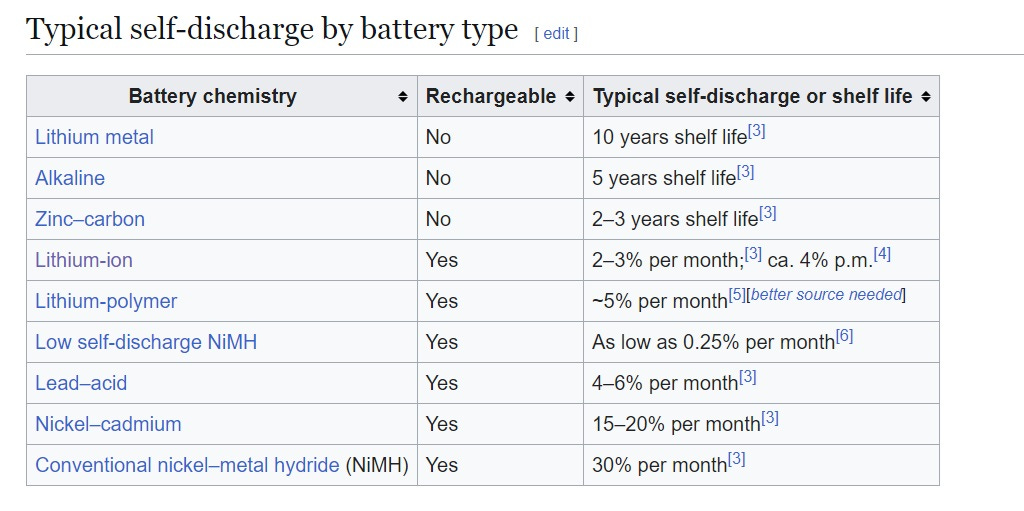

In fact, until fairly recently, I also used to think something like this, but I was wrong about how batteries work! It turns out that you can store energy in most batteries for months with very little loss:

A lithium-ion battery will lose 2-3% of its charge per month, so that’s a minimum of about 83% of its energy retained over a 6-month period.

So physically speaking, you can absolutely use batteries for seasonal storage. The reason we don’t do this is cost. It doesn’t make economic sense to install a huge amount of extra batteries that only get charged and discharged once a year, to supplement solar during the winter.

But this is also exactly why nuclear power doesn’t work for seasonal smoothing either. Suppose 100% of your power needs are met by solar in the spring through fall, but only 70% in the winter. To use nuclear as a seasonal smoother, you’d have to build a nuclear plant capable of providing 30% of your power use during the winter. But this plant would be switched off for the rest of the year. Is it economical to build nuclear plants that only get used for a quarter of the year? No. So nobody will do this.

So how do we solve solar’s seasonality problem? The standard answer in the green energy community is “build wind”, since wind works better in the winter. And in some places you can definitely do that. But wind takes a lot more land than solar, so this is often impossible.

Another answer, which I prefer, is “overbuild”. If you build more solar panels than you need during the summer, you can dramatically reduce the amount of storage you need for the winter. For example, Abido et al. (2022) find that overbuilding solar by just 30% cuts seasonal storage needs in half. With the rate that solar costs are (still) dropping, 30% or even 50% overbuilding doesn’t seem that hard.

In the end, even with overbuilding, you’ll probably need either A) a small natural gas plant to run in the winter, or B) some expensive long-term seasonal storage. A lot of people are working on technologies to make seasonal storage cheaper, but it’s still expensive:

But thanks to overbuilding, we don’t need much of this expensive seasonal storage — and certainly not whole nuclear power plants just to run in the winter. (And if some places keep small natural gas plants around to run in the winter, the climate impact won’t be that large.)

So what about nuclear? It does have a very important use case, which is when land is constrained (including in far northern regions that don’t get much sun). When geography or NIMBYs stop you from building either a solar plant or some long-distance transmission lines, you need electricity that you can generate very close to where you are. Nuclear can do that.

The problem there is that the same NIMBYs that stop you from building solar panels or transmission lines are highly unlikely to allow a big nuclear plant in their backyard. There are certainly some cases where NIMBYs could block solar farms or transmission lines but couldn’t block a nuclear plant, but they’re probably few and far between. Naturally both Matt and I want to disempower all the NIMBYs and build build build, but if we succeed at that, it’ll also make solar and transmission lines more feasible too.

So the real use case for nuclear is where you don’t have a lot of powerful NIMBYs, but where geography — high latitudes or lack of land — is the big constraint. That’s why I expect nuclear to be about 15-20% of our power generation in the future.

Nate Silver is wrong on the economy

The other day, I wrote a post about how awesome the U.S. economy is doing right now:

David Roberts cited my post to argue that “deliverism” — the idea that voters want the government to deliver substantive results — is wrong:

I think David is pretty obviously wrong here. Yes, it’s not enough to simply quietly deliver results and hope voters will notice. But imagine if inflation were still high right now, or if there were substantial unemployment. Trump would certainly be in a much stronger position. It’s not all about vibes.

But anyway, Nate Silver disagreed with Roberts that this is the “best economy in decades”, and actually called it “misinformation”:

Nate cites GDP growth as a reason to think that the current economy is average. But he’s wrong, for several reasons. First of all, total GDP growth depends on population growth. If you want to compare changes in living standards, you need to use per capita GDP instead. And here we see that except for the post-pandemic spike of 2021 (which was also under Biden), the per capita growth rate of 2.38% in 2023 is better than at any point since 2005, slightly edging out 2018’s 2.36%:

2005 and 2006 saw a bit faster per capita growth than 2023, which we’ll talk about in a second.

The other mistake Nate makes is in comparing today’s GDP growth to “the long-term average”. When David says 2023 “the best economy in decades”, it just makes no sense to compare 2023 to 1953 or 1963. Yes, the economy grew fast during the postwar decades. But David didn’t say anything about those long-ago times.

That said, 2023 still does pretty well in terms of the long-term average. Here are the average annual growth rates2 of GDP per capita over various periods:

1948 to 2023: 2.0%

1980 to 2023: 1.7%

2000 to 2023: 1.4%

2023: 2.4%

As you can see, 2023 comes out well ahead of the long-term average in all three cases.

But beyond these numerical gotchas, I think the broader point is that GDP growth is not the be-all and end-all of a good economy. In fact, in my initial post, I didn’t even list it as one of the things we want out of a macroeconomy! I wrote:

Essentially, there are four things you want from a macroeconomy:

You want high employment rates, so that everyone who wants a job has a job.

You want low and stable inflation rates, so that people know how much a dollar will be worth a month from now.

You want fast wage growth, so that regular working people are taking home their share of economic growth.

And you want fast productivity growth, because ultimately that’s what creates durable gains in living standards.

Right now, the U.S. economy is giving us all of those things.

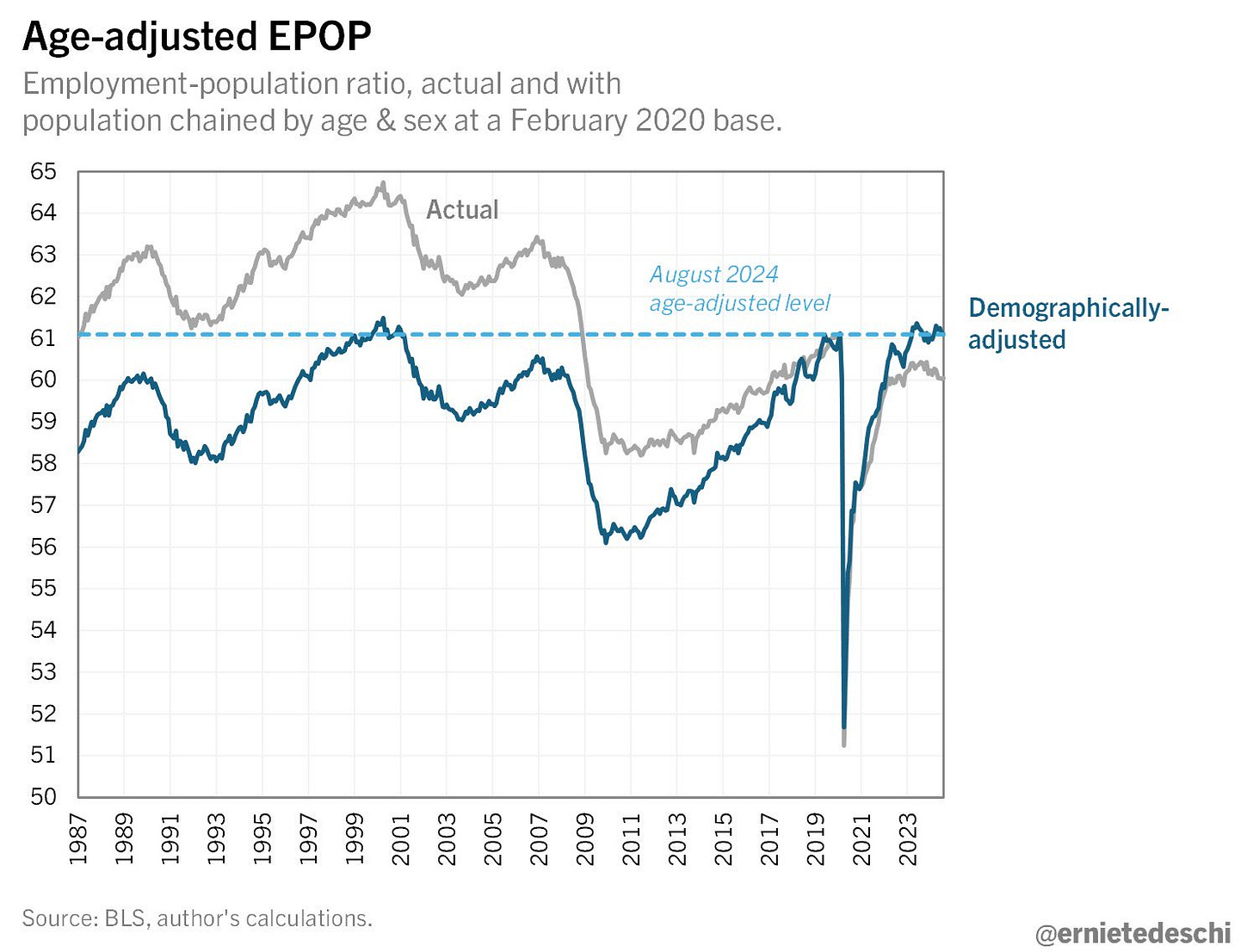

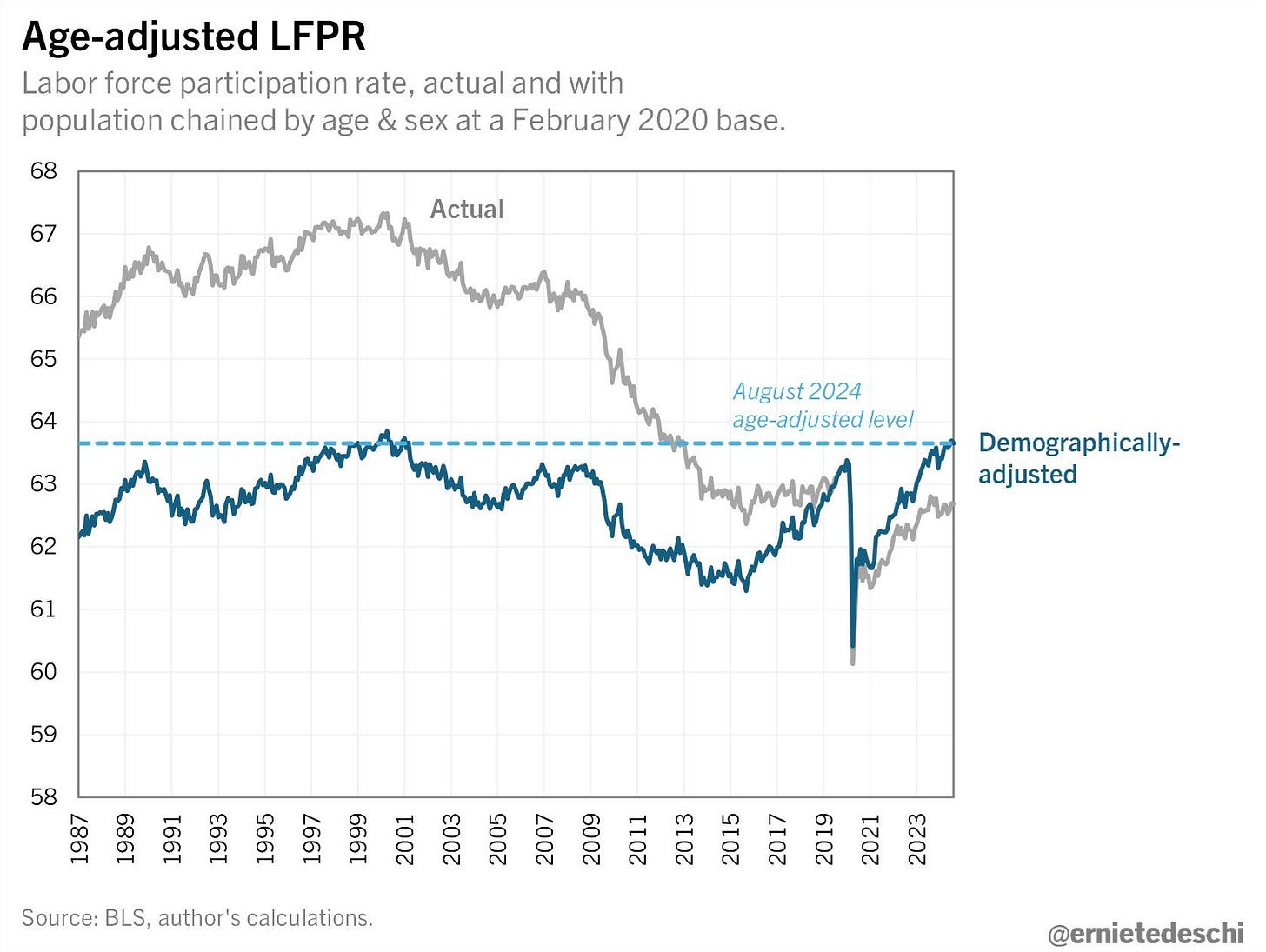

As former CEA Chief Economist Ernie Tedeschi pointed out, in terms of the labor market, this really is the best economy since the 1990s:

I would like to add my personal favorite labor market indicator — the prime-age employment rate, which is currently higher than it has ever been except in the late 1990s:

And labor productivity growth looks stronger than at any point since the early 2000s (except for in the Great Recession, where labor productivity was distorted by very high unemployment that meant lower-productivity workers weren’t counted in the average):

So those are some measures by which the economy of 2023-2024 is the best in decades, just as David Roberts said.

Nate replied to Ernie by saying that the economy is average according to his own internal model of which economic variables influence elections. Ernie replied that he’s going by the NBER’s official recession metrics. A vigorous debate ensued.

Whether you should side with Nate or Ernie in this debate depends largely on who you think economic metrics are for. If you’re deciding whether an economy ought to be popular with the voters, then maybe Nate is right.3 But if you’re deciding whether an economy ought to please policymakers, then Ernie is definitely right.

Those are different things, because what policymakers can control is different than what voters care about. Voters probably care not just about this year’s economic numbers, but about last year’s, and the year before that, and the year before that. But policymakers can’t control the past — they can only control the present and the future. So for example, it’s perfectly possible that many voters are still mad about the inflation of 2021-22, even though policymakers have brought inflation back down as of 2024.

I can’t tell voters whether to be mad about 2021 or not. But I can say that policymakers are doing just about as well as you could expect them to do, in 2024.

So let’s go back and evaluate David Roberts’ claim that the current economy is “the best economy in decades”. I think the question here is: If it’s not the best, what other year’s economy would you rather have? Let’s assume the late 90s were better than now, so let’s think only about the years since the turn of the century.

Would you rather have the economy of 2018-2019 than the economy of 2023-2024? Employment in 2019 was about the same as now — maybe slightly lower. Inflation was equally low. Real median personal income growth was faster than in 2023-24, though wage growth for regular workers was slower. Overall it was a very similar period, macroeconomically speaking.

The difference between 2018-2019 and 2023-2024, in my mind, is productivity growth. Labor productivity growth was about 1.5% in the late 2010s, and it’s been about 2.7% over the past year. To my mind, that’s a clear victory for 2023-24 over 2018-19. Productivity is the font from which all good economic outcomes ultimately spring.

How about the economy of the early 2000s — the so-called Bush Boom? Productivity growth was higher in 2000-2004 than it is now, until the mysterious slowdown of 2005 hit. Productivity growth was worse in 2005-07 than now, even though that was when the labor market was at its best of the decade. Real GDP growth during 2004-05 was a bit higher than it is now — maybe 2.7% compared to 2.4% now. Inflation was a little higher then than now, hovering around 3% in 2004-07. And though the labor market of the 2000s was never quite as good as it is now, in 2007 it came fairly close. Overall, it’s a pretty close comparison.

In other words, since the turn of the century, we’ve seen three business cycle peaks, and they’re all just about as good. If you forced me to choose one, I’d choose 2023-24, given the combination of good productivity growth with really excellent labor markets. But if you chose 2018-19 or 2005-6, I wouldn’t call you crazy.

In any case, saying that America currently has “the best economy in decades” is absolutely not misinformation.

Whose name may or may not be “Brad DeLong”

In fact, we should probably compare 2024’s growth rate to the annualized growth rates over these time periods, rather than the annual average growth rate — in other words, we should compare to the geometric mean rather than the arithmetic mean. But since the geometric mean is a little lower than the arithmetic mean, let’s be generous to Nate here and compare to the slightly higher number.

In fact, I wonder if Nate is right here. The metrics he chooses for consumption and income appear to be totals instead of per capita; I wonder if he tried the per capita numbers too, or if those might work a little better than totals. Also, presidential elections aren’t frequent, so Nate’s choice of indicators could easily suffer from specification search (overfitting). Finally, there might be structural change involved — people might care more about inflation now, but more about employment in earlier decades when inflation was low.

"Suppose 100% of your power needs are met by solar in the spring through fall, but only 70% in the winter. To use nuclear as a seasonal smoother, you’d have to build a nuclear plant capable of providing 30% of your power use during the winter. But this plant would be switched off for the rest of the year."

This seems wrong to me (or at least overly simplistic). If your plan is to use nuclear as a seasonal smoother, you don't build enough solar to meet 100% of demand in the first place. You build enough solar to meet like 85% of demand. Now you have total summer generation in excess of demand and total winter generation below demand, so you still need long-term storage - but you plausibly need _less_ long-term storage than if you didn't use nuclear as a seasonal smoother.

Is this cheaper? I have no idea. But you definitely don't have to turn a nuclear plant off to use it as a smoother.

My personal theory is that the bad vibes on the economy we are seeing is driven by the fact that real disposable income per capita by quintile is going down for the top quintile and up for the bottom quintile. This is the best evidence I can find.

https://www.statista.com/statistics/203247/shares-of-household-income-of-quintiles-in-the-us/

This is exacerbated by the fact that inflation has been falling disproportionately on goods and services that are skewed toward the upper quintile: childcare, new cars and trucks, restaurants, Uber and house cleaning, and other labor intensive services.

Home prices have increased by a very large amount and much faster than incomes across the board. This again falls mostly on the upper incomes, who are more likely to purchase rather than rent. Rent inflation has also been high, but not as high.

The upper middle class and wealthy overwhelmingly drive the discourse here and both incomes and job security are down, especially for tech workers. Urban elites like to say that they are opposed to income inequality but when faced with the actual prospect of how that plays out for them are dissatisfied.

This has been moe of a subjective analysis than usual for various reasons, mostly because data on these opinions is harder than usual to find. I would appreciate any data driven rebuttals or any rebuttals at all, other than perhaps "you are a butthead."