Hu Jintao was very underrated

Understanding China's 2020s by appreciating its 2000s

I just finished reading Elizabeth Economy’s book The Third Revolution: Xi Jinping and the New Chinese State (part of my ongoing China reading series). The book purports to be about the changes in China under Xi Jinping — changes so disjunctive that they deserve the moniker of “revolution”. And indeed, some of the chapters do deal with Xi’s bold actions in the early years of his term — his attack on the Communist Youth League and other alternative centers of power, his use of an anti-corruption campaign to defeat various rivals, and so on.

In general, my verdict on this book is that it was written too early. Published in 2018, it missed the wrenching upheavals of the past four years — the revelations of mass internment of Uyghurs, the repression of Hong Kong, Xi’s crackdown on consumer internet companies and increasing controls on social life, the shakeout in the real estate sector, and of course Covid and the ongoing lockdowns. In fact, most of the issues The Third Revolution discusses — inefficient state-owned enterprises, environmental degradation, tensions in the South China Sea, and so forth — are carry-overs from the Hu Jintao era of the 2000s. This book, therefore, is in dire need of at least one sequel, as Xi continues to outdo himself with surprising and transformative changes.

But it’s interesting that even before the big events of 2019-22, it was easily possible for writers like Elizabeth Economy to clearly see that Xi Jinping was qualitatively different from his predecessors. The combination of authoritarianism and triumphalist nationalism for which China’s current leader has become known were already apparent at the start of his rule.

That’s one big reason why although reading books on modern China is fun and edifying, it’s a poor guide to what the country is like right now. Most of the books that are still on my list to read — China’s Gilded Age, for example, or Middle Class Shanghai — are going to be primarily about the version of China’s economy and society that emerged under Deng Xiaoping and culminated under Hu Jintao. They will thus be mainly useful as background reading, to understand the situation that Xi’s “revolution” evolved in response to and reacted against.

Xi’s missteps and his moves toward totalitarianism should, in my view, cause China’s critics in the U.S. to reevaluate the system that preceded him, and — especially — the man who led China before Xi. Hu Jintao is often described as a weak leader, without his own power base within the Communist Party — a sort of gray, placeholder figure, calmly staying the course, riding on his predecessors’ successes, and letting problems build up below the surface. A sort of Chinese version of George H.W. Bush, perhaps.

But as I see it, Hu is massively underrated (perhaps also like George H.W. Bush). He wasn’t flamboyant or disruptively transformative like Xi, but he quietly addressed all kinds of problems that had a lot of people seriously worried in the 2000s.

For example, during that decade, lots of people talked about a rising wave of protests in China. A famous study found 85,000 “mass incidents” in 2005 alone, ten times the rate in the early 90s. Some of these were nonviolent, but many were violent, and a few — like the 2008 Guizhou riots over a police cover-up of a girl’s death — were enormous in scale. Western observers often spoke of this as a wave of social unrest over rising inequality and corruption, and some thought had the potential to bring down the entire regime.

Yet today, other than the Hong Kong protests and anger over Covid lockdowns, few talk about mass unrest in China. Perhaps Xi’s newly repressive policies have simply crushed dissent, but I think Hu deserves quite a bit of credit here. He was quite vigorous in tackling the regional disparities that sprung up during the first decades of China’s rapid industrialization. Hu’s initiatives included:

supports for rural businesses

an improved rural health care system

…and more. The book The Myth of Chinese Capitalism, by Dexter Roberts, chronicles how those policies made life much more bearable for people in China’s vast hinterlands. According to research by John Gibson and Chao Li, regional inequality declined during the Hu years, suggesting that these policies were largely successful:

Official sources agree. It’s highly likely that rising incomes made the inhabitants of those regions less likely to riot over things like land grabs, corruption, and police misconduct.

Another common narrative during the Hu and early Xi years was the parlous quality of China’s air and water. Much has been made of improvements under Xi (though some of this may now be reversed in an attempt to recover from Covid). But really, the vigorous efforts to address environmental problems began to bear fruit under Hu. For example, here’s an estimate of air pollution in Beijing:

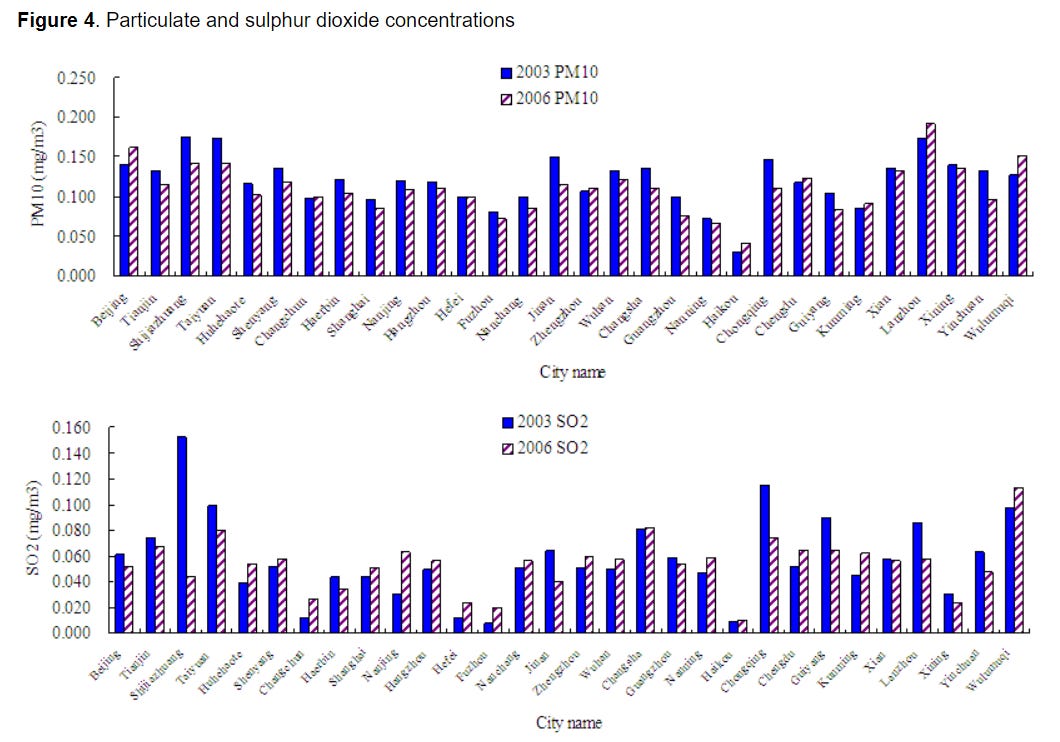

The dips in 2008 were certainly due to the special measures taken in advance of the Olympics, but the overall trend is clear. And it wasn’t just Beijing. In the mid-2000s, most Chinese cities saw modest improvements in their levels of large particular air pollution (PM10):

In foreign policy, too, Hu steered a generally more peaceful course than the saber-rattling leaders who came before and after him. Though he passed the Anti-Secession Law, his policy toward Taiwan generally consisted of outreach to sympathizers on the island, especially in the KMT. He pushed for Taiwan to be able to participate in the WTO, and said various nice things about peaceful cooperation. This rapprochement was so effective that some people even started to think that China and Taiwan might ultimately reach some sort of peaceful modus vivendi — a hope that has now been pretty conclusively dashed by Xi Jinping.

In the South China Sea, too, Hu was cautious and pragmatic, refusing the air force’s request for an Air Defense Identification Zone (which Xi later granted, leading to increased tensions). While Hu was no pushover in the international arena, it was clear that he was obeying Deng Xiaoping’s advice to “hide your strength and bide your time”. There were certainly no “wolf warrior diplomats”. It was in large part because of Hu that China gained a reputation in some quarters as the most peaceful of the great powers — a reputation Xi has now entirely squandered. International opinion of China remained decidedly mixed during the Hu years, only to plunge during Xi’s term.

Economically, Hu Jintao benefitted enormously from timing — China joined the WTO in 2001, kickstarting a massive growth boom. Hu doesn’t get credit for that, but he does get credit for steering China’s economic ship skillfully through many of the challenges that that rapid growth created. Regional inequality and pollution are two of those, of course. But another was the imbalance created by China’s chronically undervalued currency during the early years of Hu’s rule. In 2005, Hu partially floated the yuan, allowing it to begin to rise gently. A larger upward revaluation came in 2010. This helped contribute to the huge decrease in China’s trade surplus in the late 2000s (the Great Recession did the rest).

Hu also steered China through the global financial crisis and the Great Recession; China’s economy never stopped growing throughout. Here, though, Hu’s record is more mixed, since the type of stimulus he used — basically, getting all the banks to lend tons of money to real estate and related industries — caused productivity growth to slow down due to all the resources diverted away from more productive export-oriented industries. Still, getting through 2008-10 without a recession is no mean feat.

Of course, Hu also benefitted from having good help. Much of his economic stewardship and his rural equality initiatives were actually masterminded by his second-in-command, the well-loved and dynamic Premier Wen Jiabao. Leaving economics to Wen was one of Hu’s smartest moves; Xi, in contrast, has tended to take a personalistic and micromanaging approach to economic policy, resulting in a lot of dramatic moves but potentially a lot more blunders.

Which brings me to Hu’s most underrated quality: His approach to politics. Orderly leadership transitions are one of the biggest challenges for authoritarian regimes; Hu was present for two out of the three such transitions that China has ever had. He took power when he was supposed to and gave it up when he was supposed to — something that Xi Jinping is notably refusing to do. Hu’s rule was arguably the least personalistic China has had in modern times — his lack of a factional power base and his quiet, understated personality, exactly the attributes that make some people think of him as a gray nothing of a man, were actually just what China needed. Authoritarian systems, lacking rule by the people, need to at least have rule by a broad, distributed organization. By fading into the background and letting the Party handle things instead of trying to be an absolute monarch, Hu took a step toward making China’s system more stable.

And I think this fact gets overlooked by the Americans who now paint U.S. engagement of China in the 90s and 2000s as our greatest strategic blunder. But Hu’s bland, non-personalistic, peaceful management of China’s rise was actually putting it on course to become more like the “responsible stakeholder” that American leaders called for it to be. It’s very easy to see spiraling tensions with China as the inevitable result of the country’s rise — a “Thucydides trap” in which China was always destined to clash with the established powers. But had China continued to produce leaders like Hu Jintao, it seems to me that such a clash may have been permanently averted.

Unfortunately, China did not continue to produce leaders like Hu Jintao. Instead it fell victim to the classic weakness of authoritarian systems — the tendency to produce a leader who gathers dictatorial power in his own hands and then proceeds to make a string of bad decisions. Perhaps Xi Jinping, or someone like him, was always inevitable. But for a decade, Hu Jintao made it look like that was not inevitable, and that was something, at least. He deserves to be remembered more favorably than we remember him now.

Thanks for this insightful article. As a Chinese + Shanghainess, I am shocked and very disappointed with what is happening in Shanghai right now. I am worrying about my families because of the shortage of food supplies, soaring prices and the worst of all, suspended medical services and hospitals. I am a 80s so I enjoyed the economic growth in Jiang and Hu's era.

A few thoughts:

* I think Jiang Zeming is also an underrated leader. Both Jiang and Hu were selected by Deng Xiaoping as his successors, that's why they were able to continue Deng's policy.

* Both Jiang and Hu were not popular when they were in the office. Yes they were described as weak leaders. They lacked charisma as Mao, Deng or even Xi. I still remember that people were very dissatisfied with how Jiang handled the Hanhai Island incident. But the sentiment was changed around 2015, where "the toad worship" became very popular on Chinese social networks. Some people compared their ruling period as the rule of Wen and Jin in Han dynasty.

* But I bet Xi would be elected if there is a US-style election in China and the people are asked to select among Jiang, Hu and Xi. Xi is exactly the strong leader that many Chinese people are looking for. His anti corruption policy (yes although that was for eliminating his enemies) and the "wolf-warrior diplomats" gain him a lot of support. This is not surprising because most Chinese people (especially the ones from rural areas) are very conservative. Nationalism and Maoism are very popular among them. But they are often ignored by western media, just like their counterparts (Trump supporters) in US. The widening wealth gaps and social networks are making them more polarized as well.

* I think the Tiananmen square protest was a tuning point. Before that CCP was considering both political and economical reforms, according to Ezra Vogel's book about Deng Xiaoping. The political reform has been postponed indefinitely and the leader of the reform president Zhao Ziyang was removed from the office after the protest. Unfortunately there is no "what if" in history.

* I also agree that Xi did pretty well in his first few years. The most valued companies in Hu's era were banks and oil companies, while now they are tech giants. A lot of my friends in China (including the ones who came back from US) got rich in this period. I also somewhat understand his recent actions to contain some tech companies, as US and EU are doing similar things. But it seems that these policies (including the recent covid "zero tolerance" policy) were all made by his personal will. Steve Jobs said "It doesn't make sense to hire smart people and tell them what to do. We hire smart people so they can tell us what to do." Xi is the one who likes telling people what to do (in diplomat, governance, economics, education, technology, pandemic… yes almost everything).

Have you read "Haunted by Chaos" by Sulmaan Wasif Khan? This is my favorite China government book. Relies on original CCP documents to tell the perspective of Chinese leaders (but from a critical perspective).