How will you save small midwestern towns without mass immigration?

What really happens when a "flood of migrants" gets "dumped" on a small heartland town.

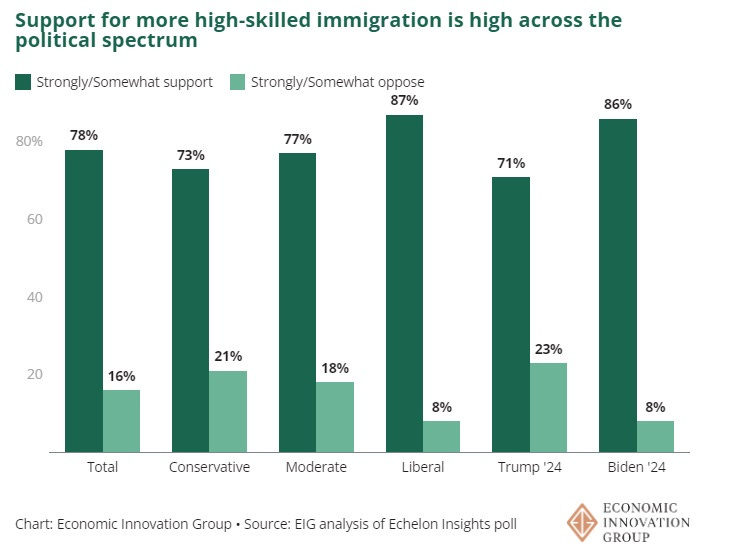

Opinion about immigration in America depends very strongly on the type of immigrants being considered. For example, people really love high-skilled immigration:

But at the same time, people really don’t like illegal immigration:

But in between, there’s a whole category of immigration that doesn’t quite fit into either of those buckets: mass low-skilled legal immigration. This is when a large number of people come to an American town who aren’t entrepreneurs or engineers or doctors, but who came through perfectly legal channels. They could be refugees, or people who get asylum, or people who come through programs like Temporary Protected Status.

They could also be people who came via other immigration channels, but who decided to move en masse to a particular destination within America — for example, a bunch of Latino immigrants who had been living in Southern California and Arizona suddenly deciding to move to a small town in Iowa. In this case, they didn’t directly immigrate to a particular town — they stopped off somewhere else first — but to the residents of that town, it feels like they did.

We don’t have a lot of polling on how Americans feel about this latter type of immigration, partly because it isn’t well-defined. But it’s definitely important. It’s the type of immigration that the Trump campaign raged against in the recent fracas over Haitians in the small city of Springfield, Ohio. And it’s type of immigration that Trump raged against back in 2016 when he targeted Somalis in Maine. In fact, mass low-skilled immigration has become pretty common in small cities and rural areas across America.

There are a few key facts we need to understand about mass low-skilled immigration. First, the U.S. government usually isn’t the one deciding which towns these immigrants move to. For refugees, we do have the Office of Refugee Resettlement, which works with a bunch of nonprofits to place refugees in specific locations. But this isn’t the Soviet Union — we don’t have laws specifying where you’re allowed to live. After they move to the initial government-recommended spot, refugees are free to move anywhere they want. And usually what you see are mass waves of “secondary migration” to specific towns that refugees decide to live in.

For example, the mass Somali migration to Lewiston, Maine was one of these secondary migrations — basically, a bunch of Somali refugees were settled in various places, but then a bunch of them got together and moved to a small town in Maine that they thought was nice. This is America; you’re free to live where you want, and refugees have this freedom too. On top of that, you also have asylum seekers and family-based immigrants, and other groups who never even go through the resettlement process at all, and just decide where they want to live from day 1.

In fact, this is not too far off from how immigration to America worked in the 19th century. As Roger Daniels details in his book Coming to America, it was common for whole towns to relocate from Europe to the U.S. at the same time, and all settle in one place. Even today, you see remnants of this pattern, in small towns that still speak European languages.

So why do a bunch of immigrants suddenly decide to descend on one American town or another? One is just word of mouth through ethnic networks — if one or two Somali families move to a town in Maine and find it’s quite nice, they may tell all of their Somali friends and acquaintances to move there, too. Pretty soon the town has a whole lot of Somalis.

Another big reason is job opportunities. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, American industry dispersed out of the big cities, aided by new highways and railroads. Factories plunked themselves down in small towns all across the heartland of America, and small cities grew up around them. Most of these factories were in pretty simple, labor-intensive industries — food processing, lumber processing, metals manufacturing, and the like. All they needed was some cheap land and some cheap labor, and a railroad or highway to sell their products to the big cities and beyond, and they were good to go. The cheap labor was often immigrant labor from Europe.

But in the late 20th and early 21st centuries, Americans — especially younger Americans — started to move away from these towns. Whose American dream is to stay in their small Midwestern town and work in the local meatpacking plant? Young people with even a modicum of talent, ambition, and wanderlust packed up and moved to New York City, or Chicago, or Los Angeles, etc.

That left the small-town factories without anyone to hire. Without labor, a labor-intensive business just goes bust. So they had basically two choices — go out of business, or find someone who was willing to work hard, day in and day out, at what most young Americans would consider a soul-crushing dead-end job. And of course there’s only one kind of person in America who will show up at a meatpacking plant or metal factory in a small midwestern town and treat it as if it’s the greatest opportunity in the world: an immigrant, without much education, usually from a low-income country.

If you’re a poor immigrant from a low-income country like Honduras, or Somalia, or Haiti, or Laos, or even the poorer parts of Mexico, the chance to live in a first-world country like America and work in a relatively clean, relatively safe factory for $14 an hour is the chance of a lifetime. You’ve really made it, if you can do that. So when a small-town factory owner who needs labor starts hiring workers from an immigrant group, they quickly tell all their friends and family, and the factory fills up with immigrant workers. This is what happened with McGregor Metal in Springfield. A similar thing happens with farms and farm workers.

If you think immigrants get “dumped” on small midwestern towns, you probably need to adjust your mental image. It’s not the government causing a bunch of Somalis to move to Lewiston or a bunch of Haitians to move to Springfield — it’s simply America’s freedom of movement and free enterprise at work. The people of an immigrant group decided to move to a town — usually from elsewhere in the U.S. — and local businesses decided to hire and recruit them. It’s all just the private sector and individual freedom at work here — the furthest possible thing from communism or socialism.

In fact, the only way you could prevent this sort of mass “flooding” or “dumping” of low-skilled immigrants into small heartland towns would be to either A) keep them from coming into the country at all, or B) institute some kind of communist-style internal mobility restrictions. Obviously the MAGA people would prefer to do the former. But because immigrants tend to concentrate in specific locations — mainly to be around people who speak the same language — you’d have to essentially cut off most or all low-skilled immigration in order to make sure that no towns in America got “flooded” with immigrants. Again, this is exactly what the MAGA people want to do.

But we should ask ourselves: Would this be worth it? After all, these “floods” of immigration are just about the only thing that can save a small town in the American heartland.

Here’s a map of all the declining places in America:

You can see that the number of declining places has accelerated in recent years. It now includes big swathes of the Great Plains, the Midwest, the Deep South, and the interior of the Northeast. This is due to a combination of factors, but fertility decline and a greater desire for city living are the main ones. There are certainly some flourishing and growing places within all the regions I just named, but there is a whole lot of orange and red on that map. Springfield, Ohio is one of them — here’s a chart of the population of Clark County, of which Springfield is the county seat:

When a small town or a small city declines in population, bad things happen. A city has a built infrastructure — roads, a sewage system, an electrical grid — that takes a lot of tax money to maintain. When the tax base shrinks, it becomes hard to pay for infrastructure that was built for a much bigger population. Things begin to decay and fall apart. Meanwhile, a smaller customer base can’t support all the businesses that used to flourish in the town, so lots of commercial spaces get boarded up and vacated. Drug people move into those spaces, and they become urban ruins. A pall of despair settles over the whole town.

When confronted with stories like this, some argue that the remaining townspeople should just bite the bullet and move to someplace better. But many lack the money, the human networks, and the simple initiative and bravery to start again in a new place. You can’t get everyone to move out of a dying town — instead what happens is that half move out and half stay, and the half who stay have a bad time of it.

So if we care about the Americans who stay in all these declining places, what can we do? A lot of people thought very hard about this in the late 2010s, viewing Trump’s election in 2016 as a wake-up call that we had to do something about declining places in America. I wrote many, many posts about it for Bloomberg. My general answer was that we should build new colleges and new branch campuses in the middle of declining regions — the “eds” in the “eds and meds” — in order to consolidate rural areas into urban agglomerations centered around universities.

Unfortunately, that’s not going to work for most places at this point. College in America is on the decline, due to a shortage of young people and a reduced tolerance for high tuition and student debt. That’s going to be a long-term sectoral trend, I think, and it means that the window to revive declining regions with university expansion has probably closed. Ideas like moving government offices out of D.C. are very marginal and won’t accomplish much in the way of regional revitalization.

And if not universities, then…what? You can call for more skilled immigration, but people with college educations and professional skills are going to move to big cities and university towns — the same place their skilled native-born peers want to live. Some thinkers have proposed “heartland visas” to encourage skilled immigrants to move to declining regions. But while that’s a decent idea, it has little hope of reviving most declining towns; skilled immigrants are just going to move to the university towns and regional cities in the declining regions, not to the truly declining places. And there are just too few skilled immigrants to make a big difference in population anyway.

That pretty much leaves just one option: mass low-skilled immigration. We know from experience that mass low-skilled immigration can and often does restore a declining heartland town to growth. Here’s a description from a report by Fwd.us, a think tank founded by Mark Zuckerberg:

Russellville is the county seat of Franklin County, Alabama, a county in the western foothills of the Appalachian Mountains…[There are] 6,000-plus immigrants and their children who, over the span of the last several years, have come to call Franklin County home…

Russellville’s longtime public librarian describes the downtown’s transformation: “We saw an influx of immigrants moving to the area looking for work, and they started opening little shops, grocery stores, furniture stores, restaurants, bakeries, places like that. We’ve now seen the entire downtown area be brought back to life, and the majority of that revitalization can be attributed to the immigrants who moved here.”…

Franklin County was experiencing demographic challenges as recently as 2010. During the preceding decade, on net, about 2,000 people, or about 6% of its population, left the county for other locales…[B]etween 2010 and 2020, the number of new immigrants…offered the population growth the county needed to enter 2020 above 32,000 people, a sizable increase over 2010…

Immigrants have been drawn to jobs at meat processing plants in the area. But, they have also started new businesses, like La Niña, and have established new churches for their growing number of Spanish-speaking congregants.

The stories of other small towns that have received a bunch of immigrants in recent years all sound the same. At first the newcomers are met with suspicion and apprehension, and schools struggle to deal with a sudden huge influx of ESL kids. But as time goes on, the small-town residents experience the optimism of the return of local growth, and most of them warm to the newcomers. The town gains a local ethnic flavor, and in general most people are either happy about the change, or at least accepting of it.

In fact, we have systematic evidence showing that this is the standard pattern. J. Celeste Lay, a political scientist at Tulane, wrote an excellent short book called A Midwestern Mosaic in which she examined the differences between two Iowa towns that got a big influx of (mostly Latino) immigrants, and other surrounding similar towns that didn’t get an influx. The book is a little dry, but if you’re really curious about the effect of a “flood” of low-skilled immigrants getting “dumped” on a small heartland town, I encourage you to read it. Here is the cover:

Lay collects both quantitative evidence (surveys, which she compares to surveys from the surrounding towns that didn’t get many immigrants), and qualitative evidence (interviews with local residents). She finds the same old American story: initial wariness and even some hostility to the newcomers, followed by broad acceptance and tolerance as locals get to know the newcomers. The Contact Hypothesis wins again, and the American mosaic becomes more colorful, etc. etc.

So if this research is right, why have we seen an upsurge in anti-immigration attitudes in America since 2021? There are two clear answers here. First, people get temporarily upset when there’s a flood of new immigrants, as there was from 2021 to 2023. Second, a lot of people are upset about the immigration they read about in the news, rather than the immigration happening in their own cities and neighborhoods. It’s a lot easier to fear people when you don’t meet them.

But in any case, if you’re upset about “floods” of low-skilled immigrants getting “dumped” on small towns in the American heartland, you should ask yourself: How else do you propose to revive those declining regions? Would you starve them of the only resource that they could possibly use to revitalize themselves? Would you just tell all the people in those towns to pack up and move to New York and Chicago? What’s your alternative plan? Because I honestly don’t see any other way those places are going to get saved.

Update: Greg Sargent went out and interviewed a city official Charleroi, Pennsylvania — another town that the MAGA people have targeted for having Haitians in it. Here’s what he found:

At a rally near Pittsburgh on Monday, Trump unleashed a volley of new attacks on Haitian arrivals to Charleroi, and used them to launch a broader argument about Pennsylvania, insisting that its towns and villages have been “inundated.”

In an interview, Charleroi Borough Manager Joe Manning flatly said that Trump’s claims are false or simply do not apply to his town in any sense….He noted that many of the Haitians work at a local packaging plant whose owner could not find workers, and went to an employment agency for help. That agency got Haitians to come work in the borough—in other words, locals, and not Harris, enticed them there—and they liked the place, Manning said, so they “put down roots.”

The key tell here, Manning pointed out, is that even now, with the Haitians already in the town, the packaging plant owner is still looking for workers.

“They ain’t taking anybody’s jobs,” Manning said, noting that they are helping revitalize the town, just as immigrants are reviving other Rust Belt towns amid postindustrial population decline. “They have occupied places that were vacant for years because a lot of people moved out of here,” he noted…

Manning shared an interesting anecdote. Not long ago, he said, a demonstration was organized on behalf of workers at a local cookware factory that is set to close, one that the area’s residents and politicians are working to save.

Among those on hand to advocate for keeping the plant open on workers’ behalf, Manning recounted, were none other than some newly arrived Haitians. Asked what this told him about the newcomers, Manning said: “They’re good neighbors.”

Sounds like the same old story. MAGA types get enraged about small-town immigration that they read about or see on TV. Then in the actual towns where the immigration is happening, the immigrants are working hard, revitalizing the town’s economy, generally being good neighbors, and winning over the long-standing residents. Again and again, America is functional and healthy at the local level, while national politicians foment hate from out of town.

I actually work in a meatpacking plant in my hometown for $15/hr. I was laid off from a good paying job and took what I could find to pay my mortgage. I work with many immigrants, mostly from Guatemala, and find them to be lovely people. They own homes, play soccer at the park, and raise their families here with dignity. We didn’t have a single Hispanic student in my high school 20 years ago. Minority enrollment is now approximately 10%. We have around 3,000 immigrants in a town of 12,000. Most issues seem to stem from a language barrier and the need for translators and ESL teachers.

When I see a family celebrating a confirmation or wedding, fixing up a house or playing at the park on a Sunday afternoon, it restores my faith in America. This is what is good about our country.

But I sometimes think about what would happen to my own paycheck if we didn’t have this influx of labor. Would I have to work 9-10 hour days 6-7 days a week to pay the bills? ICE raided the meatpacking plant in 2018 and arrested 150 workers. I was living in another state and remember being appalled. But from a purely economic standpoint and from the perspective of a working class person, that ICE raid did what our union couldn’t do. It raised wages at least 3-5 dollars an hour.

One interesting incentive my employer offers is a referral program for new employees. If you refer someone to work at the plant, you both get $100/week for an entire year. You can refer as many people as you’d like. HR told me when I was hired that a few people get an extra $800/week through referrals. Perhaps that explains some of the luxury cars in the employee parking lot…

Immigration is a complicated issue. A lot of Trump voters from local churches stepped up when the raid happened and looked after children while their parents were in custody. I encounter Trump voters laughing and joking with immigrants every day while also sharing memes about Haitians eating cats. I also know democrats in town who have never had a single interaction with an immigrant in our community.

My own thoughts on immigration are constantly evolving. Thanks for sharing this piece!

The first hurdle is convincing the people in these communities that it is in their interests. I spend a lot of time in rural areas of very blue states like Vermont and New York and they are all very much Trump anti-immigrant folks. They seem to blame immigration that they see on their TV’s but the smart kids leave (often women) and the ones who stay behind often get involved with substance problems and that is where their crime comes from.