How to have friends past age 30

A quick and simple guide.

“And our choices were few and the thought never hit/ That the one road we traveled would ever shatter and split” — Bob Dylan

I’m trying my best to find things to write about other than Trump’s tariffs, because I figure you lovely readers don’t just want to hear doom and gloom all the time. So here’s a post that people have been asking me for for quite a while.

There are a lot of things in life that I’m not very good at — foosball, debugging code, remembering people’s birthdays, and so on. It’s a long list. But one thing I am good at is having friends. Not everyone knows this about me, but in fact I’ve always been an extremely social person. I’m pretty good at assembling a cohesive group of friends, who do things together regularly and become friends with each other.1 And at least since my college days, I’ve also had quite a number of very close friends — people I can tell anything, people I know will have my back, some who feel as close as family.

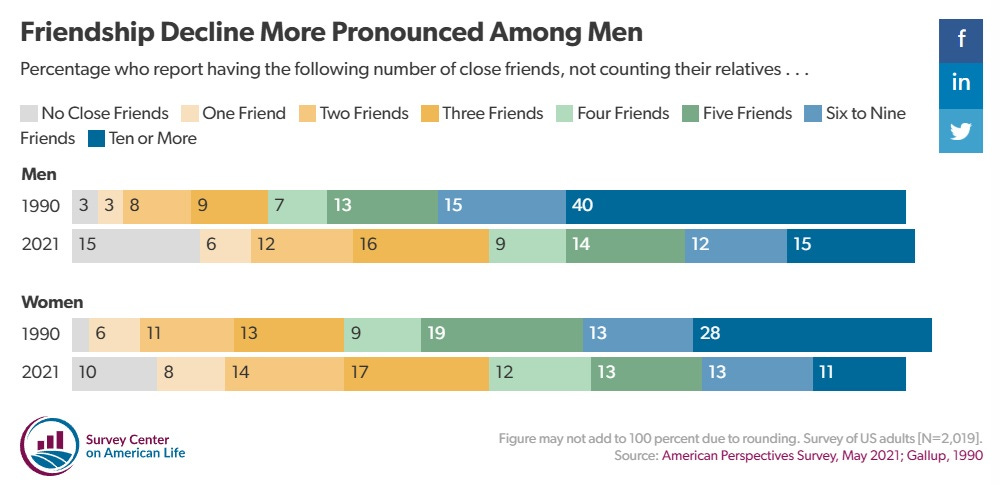

Apparently this is somewhat unusual for an American man in this day and age — or at least, more unusual than it ought to be. In 2023, Pew reported that only 38% of Americans have five or more close friends. An AEI survey in 2021 showed big drops when compared to earlier surveys:

And in 2023, the Surgeon General published a report entitled “Our Epidemic of Loneliness and Isolation”, exploring various possible factors at work.

The loneliness trend seems to predate the pandemic, and to be especially acute among young people. Derek Thompson had an excellent podcast episode back in 2022 when he interviewed the economist Bryce Ward about this so-called “friendship recession”:

Ward’s chronology of the friendship recession sure makes it sound like smartphones and social media are at least one likely culprit:

The American Time Use Survey started in 2003, and between 2003 and 2013, people spent basically the same amount of time with their friends. They spend slightly less than seven hours [per week] with friends. If you expand the definition of friends to include family and neighbors and coworkers outside of work, that whole set of people—including your friends, companions—they spent about 15 hours. And then in 2014, we started slowly kind of ticking down. And by 2021, we have this data, we’re spending less than three hours [per week] with our friends, we’re spending less than 10 hours with our companions, and what are we doing with that time we used to spend with our friends and companions? We’re now spending it alone. We’ve increased the amount of time we spend alone by almost 10 hours.

I don’t have policy ideas for combating this trend, except for the obvious one of banning smartphone use in schools. This obviously won’t work past a certain age, and smartphones are not the only cause of loneliness. I would love to tell you that building denser, less car-centric urban environments would help people have more friends, but unfortunately the evidence shows that people in big cities are just as likely — or even more likely — to be lonely compared to people who live in the suburbs.2

So while we search for policy solutions to our national epidemic of friendlessness, I thought I might offer some personal thoughts on how I’ve managed to have such a good quantity and quality of friends over the years. I realize that my own experiences aren’t universal and that my own techniques won’t work for everyone. Other people have their own approaches — just last year, the blogger Cartoons Hate Her wrote a similar guide, which is longer and more detailed than mine.

But anyway, here’s how I do it.

Why making friends gets harder after age 30

I titled this post “How to have friends past age 30”, because most of the people who ask me for advice about this, or who complain about not being able to make friends, are over 30. I think much of this advice will work for young people too. But there are definitely some reasons why making friends gets harder as you age.3

Most obviously, there are just a lot more demands on your time. A lot of people in their 30s get more serious about their jobs and careers. People also tend to get married and have kids, which takes up a lot of their time. People’s parents start getting old, and they have to do eldercare. There are simply fewer hours in the day for socializing, and you’re more tired during the free hours you do have.

Also, if you’re an educated type, much of your youth is spent in various institutions that throw you together with a bunch of other people your age and of a similar social class — high school, summer programs, college, study abroad, grad school, internships, entry-level cohorts at work, and so on. Meeting people isn’t as hard because there are higher powers doing a lot of the work for you.

But there’s another big reason that friendships get tougher as you age, and it’s that life experiences diverge. A big part of making friends is relating to other people, which requires finding some kind of commonality — some shared life experience or emotion that lets you understand someone else better by making an analogy with yourself. It would be very difficult to make friends with an alien spider, or a robot (though there are many great science fiction novels about people who surmount this challenge).

When we’re young, the people growing up around us are fairly similar to us — they usually go to the same schools, watch the same TV programs, and have broadly done similar things in life. College and other institutions sort us by social class and shepherd us through even more shared life experiences. Yes, there are plenty of differences between young people, but the structure of our society — and of life itself — means that the similarities are almost always there, ready to form the initial basis of a new friendship.

As you get out into the working world, life paths diverge. Maybe one person lived overseas and then got a PhD, while another went to work for a big company and stayed in the town where they went to college. People get married and divorced, some have kids and some don’t. Life-changing health problems, both physical and mental, become more common. Beyond these easily quantifiable factors, there are an infinitude of subtly divergent life experiences that accumulate steadily over time. By their 30s, people are much more alien to each other.

This obstacle isn’t insurmountable, but it helps if you realize it’s there. You need to understand that as you get older, most friendships will be voyages of exploration, where you spend a long time and a lot of effort understanding someone else’s unique life experiences. So be prepared for that, and try to see it as a rewarding exercise — working to understand someone else broadens your own perspective, and makes you a more well-rounded person too.

(Actually, this is probably good advice for young people too. Some young people tend to just assume that their shared experiences of school, or pop culture, or sports make them the same as their friends, and thus ignore some of the deeper differences.)

Anyway, making friends past age 30 usually means you have less time, less energy, less help, and less shared experience. But it’s still very possible.

How to have a friend group and meet lots of people

Individual friendships are great. But most people don’t just want one-on-one interactions — we want a gang of friends who all hang out together. We want something like this:4

Or maybe this:

Why? Well, first of all, it saves time; hanging out with a bunch of friends at once is a kind of economy of scale. There’s also probably some deep-seated human instinct for having a group of friends — a hunting band, or a village, or something like that. But there’s also just something magical when your friends become friends with each other. A group of N friends has N(N-1)/2 connections between them, and when most of those connections become deep ones, it adds layers of richness to the social dynamic when you all meet up.

And in fact, there’s another huge benefit to having a friend group, which is that it’s a tool that lets you make new friends.

I intentionally titled this section “How to have a friend group and meet lots of people”, instead of the other way around. You might think that in order to have a friend group, what you need to do is to first meet lots of people on a one-on-one basis, and then assemble them into a gang by introducing them all to each other. You certainly can do things that way, and I’ve done it once or twice. But a much easier way is to make new friends by inviting them to join an existing friend group.

Basically, instead of “Hey, want to come hang out with me?”, it’s easier to ask a new acquaintance “Hey, want to come hang out with me and my friends?”. The first is a bigger ask — it’s basically like a friend date (and might sometimes get mistaken for an actual date). The latter is much lower stakes. Your friend group also serves as a source of “social proof” — basically, a new friend can see that people like you, which makes them less afraid of becoming your friend.

OK, so how do you get a friend group in the first place? I wrote a Twitter thread about this a few years ago, so I’ll mainly be expanding on that.

Most importantly, friend groups are organized around shared activities — stuff that you all do together. While doing shared activities, you all talk and interact, which helps you get to know each other better; you also cooperate, which gives you the conviction that these people are on your side.

When you’re young, shared activities are often things like drinking and partying. As you get older, your tolerance for alcohol (and other drugs) goes way down, and your enthusiasm for dancing all night in a loud, sweaty, crowded club tends to wane a bit.5

It’s possible for a shared activity to be just hanging out and talking and doing nothing. In fact, this works pretty well for bonding, and young people do it a lot — or at least they did when I was young, before phones ate everyone’s lives. On TV shows like Friends and Seinfeld, the characters are often just hanging out and chatting. But as people get older and the demands on their time get more severe, they usually have less time to just slack off. And lots of people feel like they always need to be doing something with their time; if you invite someone over, you’ll probably want to have something more enticing to propose than just “come and hang out”. As a result, communal slacking is a bit of a lost art.

Anyway, in my experience, the best shared activity to base a friend group around is food. There are several reasons for this.

First of all, eating is something that everyone does, so the set of people you can invite into a food-based friend group is maximally broad — in contrast to some specialized niche activity like sailing or climate activism, where only a few dedicated people will want to join. Second, eating with friends economizes on time — you’re going to spend time eating anyway, so you might as well kill two birds with one stone. And third, when people eat, they feel happy and relaxed, which facilitates pleasant interaction.

One idea is to have a group of friends who periodically goes out to dinner. I used to have a hot pot club that went out every two weeks, and eventually tried every hot pot restaurant in San Francisco. Those outings became adventures, and occasions to do other stuff together while we were out.

An alternative idea is to cook together regularly — you can either pot luck, or alternate cooking for each other. Not only is it fun to cook together, but you also end up teaching each other how to cook a bunch of new dishes. You can do regular formal dinner parties, or keep it informal and casual. There are also variants of this approach, like drinking tea or wine together.

A second activity to organize a friend group around is entertainment. For example, watching things together on screens — TV, movies, anime, whatever — is a regular activity that can draw in a wide variety of people. The downside of watching TV together is that you end up talking less, but the upside is that you always have something to talk about.

I like food and TV/movies as a form of shared entertainment because it’s so broad — it’s a lowest-common-denominator thing that takes zero mental effort. Anyone can do it, and pretty much everyone needs some time each day to let their brain zone out. Might as well do it with friends!

(Note: For parents with small children, having your kids play with other people’s kids, or at least meeting up and letting the kids play while you chat, is the natural shared activity. The downside of this is that you don’t get to be as selective about your friend group.)

A lot of people like to organize their friend groups around activities that are more ambitious and specialized than eating and watching TV — things like hiking, or rock-climbing, or pottery, or Dungeons and Dragons, etc. There’s absolutely nothing wrong with this. But I find that these are a little harder than food and entertainment, for a few reasons. First, these are things that not everyone does; the more you orient your friendships around hiking, the more you’re limiting yourself to making friends with people who hike. Second, unless they’re pretty dedicated, these aren’t things people do every day — therefore, they represent additional demands on the time of busy people.

Of course, hobbies like hiking are great, and it’s nice to do them with friends. One technique is to build up a large diverse friend group organized around things like food and entertainment, and then find a few people from that group who want to go hiking with you. In my experience it’s easier to do it this way instead of making hiking your whole social scene.

Anyway, another thing that I find really helps with the formation of a friend group is a gathering place. In Friends they all go hang out at a particular coffee shop, or at Monica’s apartment. In Seinfeld they all go hang out at Jerry’s apartment, or at their favorite diner. Basically, a good gathering place is a house or “third space” whose location is fairly central and convenient for everyone.

In TV shows, of course, they limit the number of sets to save money and build audience familiarity. But I find that a regular gathering place (or two) makes it a lot easier to have a stable friend group, for a few reasons. First, it helps with coordination of the shared activities — if you always have to find a different place to watch Star Trek, it raises the activation energy required for people to hang out. Better to just go to the one house where everyone watches Star Trek.

Second, a gathering place helps with serendipity — if people in the group get used to going there, they’ll encounter each other more often. And if they bring new friends by, it becomes a place to meet new friends too.

(As a side note, I believe that small homes and crowded third spaces are a big part of why Japanese people have an even harder time hanging out with friends than Americans do.)

Once you have a shared activity and a gathering place, it becomes very easy to use the group as a vehicle for making new friends. Just invite them over to cook, or invite them out to hot pot club, or invite them over to watch Star Trek together. If they click with the rest of the group, you have a new friend.

And note that a friend group helps you meet new people without even trying, because your friends bring in new people too. You’re not doing all the work yourself. A friend group is like a snowball that just keeps accumulating more prospective friends once it reaches a certain size. This helps balance out the attrition from people moving away.

And you don’t have to just keep doing the same things in the same places. Once you have regular hangouts with your friend group, you can organize more ambitious activities. For example, one fun thing a lot of people do when they’re young, but which I only really discovered in recent years, is group travel. It can take a lot of money, and everyone has to be available at the same time — it’s not the kind of thing you can regularly do.6 But it creates lots of opportunities for bonding.

Of course, this all leaves the question of how to meet prospective friends in the first place. If you just moved to a new city and you don’t know anyone, you’re facing a cold start problem — you’ll need to make a couple of initial friends in order to get your friend group going.

In fact, this is the hardest part of making friends. There’s no reliable one-size-fits-all solution to the cold start problem, because it depends on your circumstances, and because a lot of it ends up being luck. It requires you to be at least a little bit outgoing — to just walk up to people and ask them to hang out — without the benefit of an existing gang to back you up. Often it can take a couple months or more before you meet those first one or two people who really click with you — especially if you’re not a naturally outgoing person.7 Three common strategies for this are:

Meet a coworker or two that you really click with.

Join clubs or groups associated with your hobbies (e.g. hiking, or taking care of rabbits, or art), or go to regular events based on these hobbies, and then see if you click with one or two people there.

Get your friends from the city you moved from to introduce you to their friends in the city you’re moving to.

If all else fails, you can just get on X or Bluesky and meet people that way. This has worked surprisingly well for a number of people I know. I rarely say anything positive about those social networks, but I must admit they’re the best for making friends.

How to build close friendships

A group of friends who all hang out together is wonderful, but it doesn’t automatically lead to really close personal friendships. Ideally, I believe, you should have some friends who are more than just adult playmates — people you can confide in, people you can rely on, people who really understand who you are. These are your “chosen family”. They’re some of the most important relationships you’ll have in your life — in a very real way, they define who you are as a person. There’s no hard-and-fast boundary between close friends and more casual friends; it’s a spectrum. Closeness tends to develop gradually over time, and it feels a little different in each case.

Good advice about how to build close friendships is actually more common than advice about how to build friend groups. You can read a bazillion New York Times articles and Reddit threads on the topic, and they all tend to mostly say the same things. So I’ll keep it brief.

There are basically two things that define a really close friendship: understanding, and interdependence. Your close friend has to understand who you really are, and you also have to know that you can count on them if you need help. If a friendship has only one of those things and not the other, it’s not really a close one.

Understanding gets built up over time, but it can’t reach a truly deep level without confessions. We all have certain things that we’re reluctant to tell other people about ourselves — not necessarily secrets, but core truths of our lives that we don’t like yelling at everyone we meet at a party. Occasionally these might be facts about your life, but usually they’re just vulnerabilities and desires and fears.

In order to make a really close friend, you have to tell them at least some of those things, and they have to tell you theirs. You have to have moments when you open yourself to another person and make yourself vulnerable to them. And you also have to have moments where they do this for you. You don’t both have to do it at the same time, but it has to happen on both sides.

Those moments of vulnerability and openness can happen in a group setting, but much more often they happen one-on-one. So you have to hang out with your friends outside of the group sometimes.

The other thing you need for a close friendship is interdependence — you need to know you can rely on your friend, and they need to know they can rely on you. There’s no way to prove this in an absolute sense, of course — you’ll almost certainly never know if your friend would really lay down their life for you, because that sort of situation almost never actually comes up.

Instead, what you need is to ask favors of your friends, and do favors for them as well. Maybe you help them put together a bookshelf, and then borrow their car. Maybe they take care of your rabbit, and you help them find a job. Etc. You have to not be afraid to ask for favors from your close friends, and you have to want to do favors for them too. Don’t intentionally test people by seeing if you can get them to do stuff for you, of course. Just wait until you really need something, then ask. Eventually this builds up, like a muscle — whenever you learn that your friend needs help, you won’t even think twice before you offer to do it.

Anyway, building close friendships can happen serendipitously, and if you have a good friend group and you do one-on-one hangouts too, it probably will. But I think there’s nothing wrong with being deliberate about it, and pushing things along, especially in terms of having those deep, revealing conversations. People over 30 have such incommensurate life experiences that you probably need more deep conversations than if you were young. And yet as people age, they often become more closed-off and less willing to spill their deepest, darkest secrets to someone from their hot pot club.

So I think you have to work at it. Having friends is one of the most important components of a complete, fulfilled human life. It’s just too important to leave entirely to chance.

Update: My friend Jessica, who is even better at having friends than I am, writes:

For those who can’t afford group travel, but want to make similarly intense memories: creating some traditions around people’s birthdays or a holiday everybody loves can give the friend group something to look forward to each year. As for getting people to vulnerability, that old New York Times article with 36 questions that lead to love can be great to play with friends.

Board games work well for the shared activity, but they attract a certain kind of human. But they don’t have the limiting factor of television and they work for people who have intense food allergies and they create their own inside jokes and group knowledge.

Ironically, only about a quarter of the people in the photo at the top are my friends. The others are friends of friends, who just happened to show up at a party that was partially in honor of my birthday. Everyone in the photo agreed to let me post it on Substack.

There are various urban amenities that can decrease loneliness a bit — low crime, more parks and community centers, etc. — but the effects aren’t huge.

Yes, the “friendship recession” is more acute among the youth, but I believe this to be primarily a cohort effect rather than an age effect; once Gen Z gets into their 30s, it’s going to get even worse.

I never thought Friends was funny, but the other day I met a guy from Iran who told me that all throughout his childhood, even as he was taught to stomp on the American flag, he and his peers secretly loved and idolized America because they watched Friends. So I have begrudgingly come to respect the show’s value as a tool of soft power.

This is less true for old Japanese guys, who tend to be much more raucous than their younger peers.

Well, usually not. Every year my friends and I take a big (and growing) group of friends-of-friends to Taiwan for New Year’s. We put everyone in a big WhatsApp group, from which we recruit people for various activities — food, karaoke, day trips, bars and clubs, onsen, etc. This year we had over 90 people! We call this the “Traveling Neighborhood”.

I am a naturally outgoing person, and I talk to strangers a lot. This has resulted in a few lifelong friendships, and some very strange dates.

Lovely, thoughtful and useful post, Noah.

I got divorced at 51, then mothballed my business and move continents to a city where I had visited often but never lived (London).

I never maintained a friends group from high school or college, and yes, the close friends I had at 51 were mostly those I made around my mid to late 20s after I'd moved to Cayman but before we all had kids and got busier and busier.

I have, though, been successful at building a number of new and close friendships, with close friends I've made in the last 7+ years since moving to London, ranging in age from 20s to 80s.

I don't do small talk or shallow conversation, so my tribe is those who like to be open with ideas, feelings, themselves.

Your post makes me think about tools and methods for making friends, particularly the idea of hanging out in groups as a tool for that. Over the last two years, Ben Brabyn has been running "Walkabouts" in central London. A set day of each month at the same place and time where people simply gather and go for a one hour walk, encouraged to bring a +1 and to bring their curiosity. These have been wildly successful, we now have over 20 of them internationally and more and more each month. I sense it is because people crave meeting new and interesting people. If anyone reading this wants to learn more, message me!

As for myself, when I moved to London, I simply found myself asking people I got to know "I want to meet interesting people doing interesting things". This lead to many, many introductions to meet people 1:1 to talk ideas. Some of those were business-y, some around topics of mutual interest (eg Econ / Geopolitics / Leadership / Coaching geeks). Some became mentees, some became friends, a few became close friends (over time).

Again, thanks for the thought-provoking post!

"I would love to tell you that building denser, less car-centric urban environments would help people have more friends, but unfortunately the evidence shows that people in big cities are just as likely — or even more likely — to be lonely compared to people who live in the suburbs."

But you can make a lot of friends by working on zoning reform together!