I just finished attending Kilkenomics, an annual festival in the small Irish city of Kilkenny. Kilkenomics is a rather unique event, in which Irish comedians interview foreign economists and econ commentators about various topics. My interviews were mostly about war and the changing global order — grim topics that are on a lot of people’s minds these days. I tried to keep things as light as I could under the circumstances, mostly by making fun of the British. All in all, it’s an experience I would highly recommend.

But my stay in Kilkenny drove home a fact that I knew on an intellectual level, but had never viscerally experienced: Ireland is an extremely rich country. Kilkenny’s small downtown is as nice as any I’ve visited in Europe, like a little piece of Oslo or Zurich or Amsterdam — a few blocks of little shops and cafes and restaurants and pubs and department stores, with an old castle and some cathedrals thrown in. Outside of downtown, the landscape quickly shifts to an American-style car-centric sprawl of single-family homes amid rolling green fields.

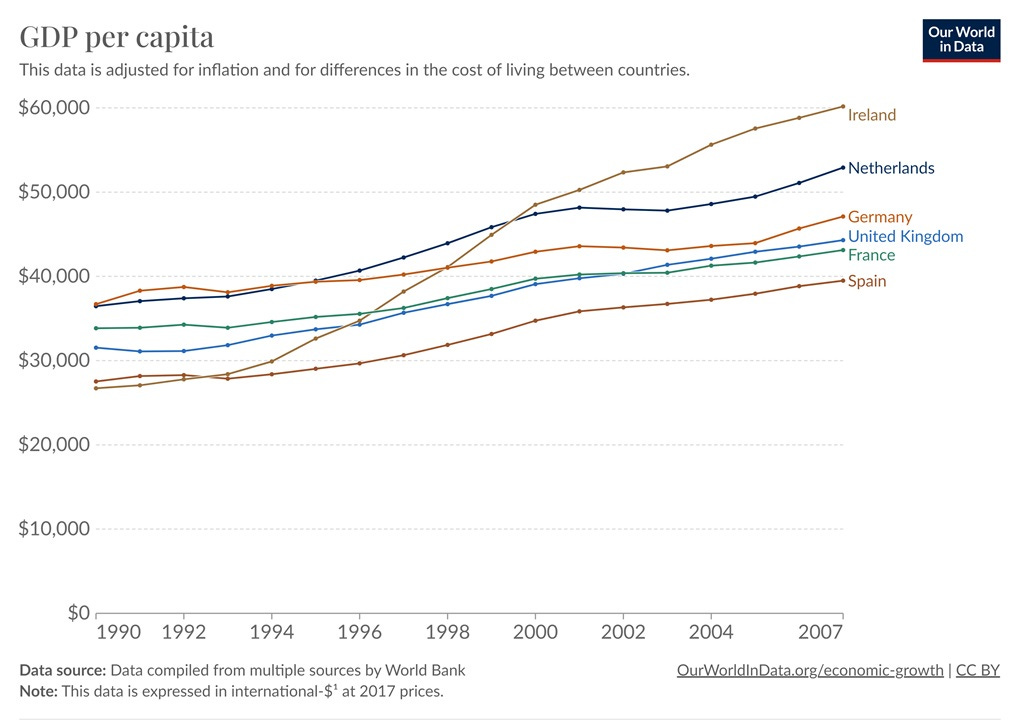

This is not how I would have imagined Ireland when I was growing up. My mental visions of the country were always ones of poverty and strife — the potato famine, the penniless migrants flooding American shores in the 1800s, Jonathan Swift satire, James Joyce novels, the Troubles, and so on. And as recently as 1991, there was still a bit of truth to the stereotype — Ireland had a lower per capita GDP than most of the other countries in West Europe. But 16 miraculous years later, the situation had reversed:

Of course, you may have heard that Ireland’s GDP is massively overstated. And indeed it is — now. The graph above ends in 2007 for good reason; if you look at a more recent graph of Irish GDP, it soars to ridiculous heights — over $100,000 per person. The country is rich, but it’s not that rich.

A recent article in The Economist explains what’s going on. Ireland’s GDP is overstated for two main reasons. First, and most importantly, Ireland is a famous tax haven — its low corporate income tax rates give multinational companies an incentive to book as much of their profit as possible at their Irish subsidiaries. For European companies, this usually required actually relocating their activities to Ireland, but the U.S. has a strange corporate tax system that allows companies like Google and Apple to engage in various other schemes to book profits in Ireland without actually doing anything substantial in the country, inflating Ireland’s GDP. A second piece of weirdness was aircraft leasing, whose statistical treatment doesn’t make a lot of sense.

In an attempt to stop exaggerating its GDP, Ireland implemented a special statistical system called GNI*, or modified gross national income. Ireland’s GNI* is a little over half of its GDP.

But even this dramatic adjustment means Ireland is still quite rich. It has 5 million people, so its GNI* per capita is about $54,000 — about 16% higher than the UK’s GDP per capita, and above either Germany or France.

And as The Economist shows, GNI* didn’t really start to diverge from GDP until 2000, and even in 2007 the divergence was pretty small. The stunning growth of the Irish economy in the 1990s and early 2000s was very real. And despite getting hit famously hard by the bursting of the housing bubble in 2008, Ireland retains its status as one of the world’s richest economies. The country may no longer be the “Celtic Tiger”, but its gains during that glorious epoch appear secure.

Ireland is also part of a small, elite club of countries that is richer than its 19th-century imperial overlord, along with South Korea, Poland, the Baltics, and a few others. It’s Britain’s turn to be the shabby, dysfunctional cousins.

I’ve written a lot about Poland, and everyone reads about South Korea. But how did Ireland do it? And can other countries copy the feat? Obviously it’s never possible to know exactly why a country got rich, but looking at the history, we can piece together a plausible story.

Ireland is a high-tech export powerhouse

I like to start these posts by asking what each company specializes in. And a good way of figuring that out is to look at exports. Ireland’s exports are heavily weighted toward the biomedical and pharmaceutical industry, with some high-tech electronics manufacturing as well:

If you go back to the “Celtic Tiger” years, electronics manufacturing was a little more prominent, but the basic pattern was probably the same. In general, Ireland was a pretty manufacturing-intensive economy during its boom years, in the same league as South Korea or Germany.

Ireland is a small country, meaning it can’t really make much stuff for the domestic market, because there just isn’t much of a domestic market. So Ireland’s economic success naturally involved a lot of exports. In fact, Ireland is traditionally more export-oriented than South Korea:

In other words, the Celtic Tiger looked much like the Asian Tigers did — a country that made a lot of high-tech products and sold them to the rest of the world. Of course, a country can’t get by on export manufacturing alone — you need to have a robust local economy to circulate and multiply the gains from export revenue. But export manufacturing is useful for a number of reasons. Manufacturing inherently tends to have rapid productivity growth. And many people think exporting raises productivity growth as well, by forcing local companies to compete in global markets and helping them to absorb foreign technologies.

One reason Ireland has been able to accomplish this is its special relationships with two important economies: the U.S. and Europe.

Investment from America, markets in Europe

If you want to export a lot, you need somewhere to sell your products. Ireland’s export destinations are actually very diversified:

Europe obviously looms the largest here, which is unsurprising because of simple geographical proximity. But the fact that Ireland is part of the EU — and before that, was part of the European Economic Community — certainly helps. Ireland’s embrace of Europe stands as a stark contrast to Britain, which is still reeling economically from Brexit.

But when it comes to investment capital, Ireland has an even bigger ace in the hole — the United States. Just as with other recent development stars like Poland and Malaysia, foreign direct investment is very important to Ireland’s economy. And the U.S. is by far the biggest source of that investment. This is from a recent report by New Zealand’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade:

Ireland is the most popular destination for new Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) projects in the EU, when measured on a per capita basis. The attraction of FDI to Ireland has been a cornerstone of Irish government policy since the 1960’s and FDI now plays a very significant role in supporting the Irish economy…

Investment has come primarily from the U.S., with the large Irish diaspora overseas helping to facilitate connections. In 2020, U.S. FDI in Ireland stood at USD 390 billion, more than the U.S. total for Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa (the BRICS) combined. While investment from all sectors has been welcomed, those offering high value-to-volume products for export (e.g. ICT and Pharma) have been favoured…

In terms of global distribution, 847 of the multinationals investing in Ireland are from the United States, 354 companies are of European origin – with almost half of those from Germany and France, 136 are UK origin client companies, and 212 come from across the rest of the world[.]

One report I read referred to Ireland as “an intermediary between Silicon Valley and Europe”.

As the report mentions, the U.S. has a big Irish diaspora — about 36 million strong, over seven times the population of Ireland itself. But it’s not just the diaspora that creates a bond between the U.S. and Ireland — it’s the idea of the diaspora. Because the Irish were the first great wave of foreign workers to come to America after its founding, their story is fundamental to America’s self-identity as a nation of immigrants. Lots of Americans who don’t have Irish ancestry like to imagine they do — for example, Bill Clinton, whose claimed Irish roots could never be verified. Everybody gets drunk on St. Patrick’s Day.

That combination of ancestral and sentimental attachment shows the power of a strong diaspora. Over the centuries, Ireland’s tendency to send its young people abroad has traditionally been seen as a weakness; since 1990, Ireland has been an object lesson in how outmigration can boomerang and eventually become a strength.

Irish policy does it all

Roughly speaking, there are three varieties of development policy. These are:

Liberalization

Capacity building

Industrial policy

Liberalization just means removing the barriers to economic activity — high taxes, regulation, trade barriers, and so on. Capacity building means investing in things like education, health, and infrastructure. And industrial policy can mean lots of different things, from subsidizing exports to courting foreign investment to promoting specific industries.

A lot of ink gets spilled by people who argue about these approaches, but when you look at the development success stories, they all tend to involve some portion of each. And Ireland is no different.

Ireland’s journey toward liberalization began early. Even back in the 1950s when Ireland mainly exported farm products, its leaders recognized how crucial foreign market access was. In the 1970s, economic policy influencers like T.K. Whitaker successfully argued for free trade — which is essential if you’re a small country without much of a domestic market. The EEC and EU were, of course, essential for this. In fact, one big growth advantage of small countries over big ones might simply be trade openness; in a small country, everyone realizes that the domestic market isn’t enough.

Ireland also has famously low corporate tax rates, which are part of what give it its reputation as a tax haven (the other part being some weird tax loopholes). But in fact, this wasn’t always the case. Until the late 90s, Ireland had high tax rates on every sort of corporate income except manufacturing, for which the rate was very low:

This is sort of a combination of liberalization and industrial policy. Preferential low rates on manufacturing helped bias economic activity toward things like electronics and pharma; without this split rate, Ireland might have become finance-heavy like the UK.

In fact, one wonders whether cutting tax rates for other kinds of corporate income might have inadvertently pushed Irish investment away from the strengths of the Celtic Tiger period and toward things like housing speculation and tax haven shenanigans. But it’s also the case that tax havens tend to grow faster than other countries. Part of the reason might be that many tax systems only allow companies to take advantage of a country’s low tax rates if they actually move their factories to that country. So Ireland might be absorbing foreign technology by luring companies in with tax arbitrage.

Partly as a result of low tax rates and various other business-friendly policies, Ireland regularly ranks near the top of various “competitiveness” rankings; in 2023 it was #2 on IMD’s global list, behind only Denmark, with especially high rankings in “business efficiency” and “government efficiency”.

Some thinkers like Ha-Joon Chang have concerns with FDI as a driver of development. They worry that foreign companies won’t let go of their best technologies, and that foreign brands will crowd out domestic ones, ultimately limiting a nation’s ascension to the top of the value chain. Irish policymakers have shared this concern, making various attempts to promote domestic innovation. So far it’s not clear how effective this has been (especially because Ireland’s tax shenanigans make macro data difficult to assess).

And of course to build a rich economy, one thing you definitely need is a lot of skilled labor. There are two ways to get skilled labor — education and immigration — and in general you should use both. Ireland did. Its baby boom was bigger and lasted much longer than other rich countries:

Ireland has also done a great job of educating its young people, with one of the highest rates of tertiary education in the OECD.

But Ireland has also imported large numbers of workers. In the 90s, a traditional pattern of outmigration reversed, and people started moving to Ireland en masse:

These immigrants tend to skew young. And they’re disproportionately high-skilled; in 2022, more than half of immigrants to Ireland had a university degree or similar. Some of this is natural self-selection, but Ireland also has policies in place to promote skilled immigration.

They also come from a mix of countries. Ireland’s Central Statistics Office found that in 2022 there were 141,600 total immigrants, 29,600 of whom were returning Irish citizens. About 26,000 were from the EU, about 42,000 from Ukraine, 4800 from the UK, and about 39,000 from other countries.

At a time when many countries are becoming hostile to immigration or at least questioning its value, Ireland has generally continued to embrace foreign workers. There are some signs that East European immigrants aren’t quite as successful as their West European and global counterparts, and I did encounter a couple instances of stereotypes being leveled at East Europeans during my stay in Kilkenny. In the last year there has been a small backlash against refugees.

But overall, Irish people are consistently more positive about immigration than almost anyone else in Europe. And for what it’s worth, my brief personal experience bore this out. Irish people I talked to seemed very aware of how important foreign workers — especially skilled workers — had been to their country’s economic ascent. Some mentioned pub culture and sports as key mechanisms of cultural integration. Others opined that Ireland was a “high EQ country”, whose people specialized in managing top engineers from all over the world. Nobody I talked to seemed to regard Irish immigration policy as anything other than a smashing success.

In other words, there are a lot of things Ireland did to try to produce an economic miracle. It liberalized its trade policy, cut taxes, created a favorable climate for business, and drew in a bunch of immigrants. But it also encouraged manufacturing, tried to promote domestic innovation, and invested heavily in education. Ireland did it all, and somehow, it worked out.

What next for the Celtic Tiger?

Ireland’s biggest policy challenge right now, without a doubt, is housing. Rapid immigration, along with replacement-level fertility, has sparked a population boom:

But this boom hasn’t been matched by a boom in new housing construction. Ireland is still extremely wedded to the idea of single-family homes; very little of the population lives in apartments. The country'’s permitting process is possibly even more onerous than America’s; I met some YIMBYs who had come to Ireland to study the country’s mistakes.

Housing is regularly listed as the biggest challenge to continued FDI in Ireland, and overcrowding is probably one reason why anti-immigrant politics have finally made it to Ireland’s shores. If the issue doesn’t get solved, it’s not inconceivable that Ireland could follow Britain into genteel decline.

But for now, Ireland is still riding high on the success of its Celtic Tiger era. A country that was once subjugated and looked down upon by its neighbors is now a beacon of wealth and high-tech skill.

And I think this teaches us a crucial lesson about national development. If you went back to 1923 and asked people whether Ireland would be richer than the UK in a hundred years, how many of them do you think would have said yes? How many would have laughed in your face? And yet here we are, a century later, and that’s the reality. Now pull out a map of the world, and pick out some countries that most people think don’t have what it takes to get rich. Where do you think those countries will be in 100 years?

Are you sure?

P.S. - Here are a few random (unedited) pics I took in Kilkenny…most are just standard “old castle and green countryside” stuff, but a couple show what the little downtown area looks like.

Ireland makes quite a bit of its money off US-developed IP transferred from US tech and pharma companies to Irish subsidiaries. These companies charge royalties on the IP (eg Apple and Google pay royalties on sales of their products in the US to European tax havens like Ireland). This gives them a tax deduction (for royalty payments) in the high tax US and very low taxed income in Ireland (also Lux, Switzerland, Netherlands).

It is the ultimate insanity of the US tax code that tech developed in the US by a US company generates all of its global royalty/trademark revenue in Ireland, which had nothing at all to do with it.

As for manufacturing, most of this is pharma where the cost of manufacturing inputs is very low relative to the price of the products. Just a way to keep the profits from EU sales in Ireland and keep the marketing and overhead expenses in high tax Germany, France etc.

Ireland is not like an Asian Tiger. Who is Ireland’s LG or Taiwan Semi? Ireland (outside of Ag) has essentially no homegrown powerhouses (except for the foreign companies who have moved their HQs to Ireland for tax purposes, and maybe Smurfit and CRH)

Don’t get me wrong - Ireland has done very well, I did business in Ireland for 30 years, I like the Irish and it is a fun place to visit (couldn’t pay me to live there).

Also, if you want to get a more complete picture of Ireland, stroll around Limerick as well as Kilkenny.

I just want to add that as an American who lived in Ireland for three years: Ireland isn’t actually a very rich-feeling place to live. Some things not mentioned in this essay:

1/ Ireland has a relatively low median wage for a wealthy country paired with *extremely* high median costs. When I lived there, the cost of living in Dublin *was (edit: this was true back in the mid-2010s, but now London is again ~20% more expensive) higher, even, than London, but salaries don’t match (for the same position they were often half, in my experience), even for highly-paid tech workers and professionals. Like most tech workers I knew there, my wife and I crammed into a tiny shared townhouse apartment, and we were among the lucky ones! People with more modest wages lived in unspeakable tenement-like conditions or were among the many homeless. The dream of getting on the property ladder seems impossible even for highly-educated professionals (something that Ireland does share in common with Silicon Valley!).

2/ This is worse when you add in the very high income taxes, VAT, and capital gains taxes which leave the median resident with a extremely high tax burden, in contrast to the zero-to-low tax paid by their employers. And what do you get for these taxes? Very little, actually! The public healthcare is far inferior even to the austerity-drained NHS across the Irish Sea. Maternal healthcare was extremely poor quality, especially since it was complicated until recently by Ireland’s abortion ban (which outlawed a lot of maternal healthcare, including lifesaving treatments for things like ectopic pregnancies!). You pay the same TV tax as your British neighbors but get the inferior RTE instead of the BBC. There is hardly any public transit in Ireland, with Dublin being one of the few large cities in Europe without a metro or even a train to the airport. Combined with the low density, this leaves the medieval streets *crammed* with traffic and some of Western Europe’s worst local air pollution. Outside of Dublin, there just isn’t anything, transit-wise. Intercity trains are extremely sparse and expensive, and no other cities outside of Dublin have any public transit more than buses. In contrast to most of Europe, there isn’t any subsidized childcare, either--and prices are even higher than the American average! Parental leave and child tax credits are miserly, especially for fathers. Then there’s the small, but noticeable stuff: trash everywhere, crumbling streets and sidewalks, tumble-down buildings, “crap towns,” and even a surprisingly unlovely cityscape through much of the city of Dublin, exempting a few of the more posh neighborhoods. It just doesn’t look rich most places in Ireland. You’ll find yourself thinking that much-poorer countries in Eastern Europe feel far richer. All-in-all, living in Ireland is like living in the US (with its notorious lack of public services), but paying a Nordic tax rate for the privilege!

3/ Irish politics are a downer. Ireland avoids a lot of the populism or ethno-nationalism that has plagued the rest of the West in the last few years, but it’s replaced by a tyranny of low expectations. The same two center-right parties traded government for the entirety of Ireland’s independent statehood. One was vaguely more rurally-oriented than the other, but otherwise, they’re identical. There was no viable center-left alternative, even. Which seems very odd in Western Europe. And extremely odd when even the neighboring UK has at least had Labour governments. It’s not just the monoculture of meh neoliberal ideology that sucks up the oxygen of political optimism--it’s also a very uncompetitive two-party political dynamic wherein the two parties are so undifferentiated and the voters don’t expect much from either of them. When corruption scandals broke, as they often did, it was greeted with a shrug. Everyone I met when I lived there just kind of expected that the government couldn’t do things like fix the housing crisis, finally build a rail line to the airport, not waste the tax windfall, etc. This was frustrating to me, coming before the post-2016 moment in the United States where Americans also gave into a fatalistic shrug as the “Do-Nothing” country. But at least in the US, there’s a kind of libertarian excuse where at least you don’t pay high taxes and therefore expect better state capacity. In Ireland, you pay for premium and get budget.

4/ Ireland has no nature to speak of. Yes, the tourist brochures are all sheer cliffsides and emerald fields and bracing sea air and all that, but when you live there you realize that those cliffs are owned by some landlord who charges you entry to snap photos and directly in the other direction are a bunch of fenced-in allotments with ugly 1970s cottages on them built as an investment. Camping? Forget about it! Want to take a hike? There are a few fenced off areas that everyone crowds into on the weekends. Wilderness? Where!? There is not a scrap of land on this entire (very underpopulated!) island that isn’t owned by somebody, seemingly. And, long ago, any intact Nature was stripped for parts: There is hardly a forest in the entire country. It has one of the lowest biodiversity measures in the world. National parks are few and paltry. Even when you compare with the UK across the water--with all its population and extremely unequal legacy of land ownership and intensive cultivation and development--Ireland feels like a sprawling exurb. If rich countries can afford to again restore a rich nature, Ireland is far from rich.

5/ Rich countries have good schools and Irish people are among the world’s most educated. So why is it there Ireland has no top-quality (secular) education system!? Because it doesn’t. *Most* of the public schools are actually Catholic schools! Read that again and be amazed. More than 95% of all schools in Ireland are explicitly Catholic or Christian! This is a weird holdover from the (not too distant) era where the Catholic Church was basically the state in Ireland. Nor do these theologically-oriented public schools impress: Ireland is middling on international ranking of educational outcomes for schoolchildren. Like in the US, there’s a big gap in quality between K-12 and elite university, with Ireland really punching above its weight in the latter and seriously disappointing in the former.

Among many other reasons, these factors make living in Ireland very discordant. You know that, on paper, you are in a rich country. So why doesn’t it feel that way?

Most immigrants/expats, like me, hit their limit after 2-3 years of living there. Especially when it came time to plant roots and settle down, the practicalities and appeal just weren’t there. And it seemed like every younger native Irish person felt the same, dreaming of life in London, New York, or Dubai. So, a city like Dublin, more so even than other large cities, felt transient and very young. Which just seems like the kind of thing that isn’t sustainable. You can’t build an economy on young people from elsewhere coming into study or work in early-career jobs before leaving, can you?