Housing is at the heart of America's economic problems

We're propping up prices to boost old people's wealth. But that's shutting young people out of the capitalist system.

“Can I get my punk ass off the street?/ Won’t die on the vine/ Wanna knock it all down” — Third Eye Blind

Peter Thiel doesn’t seem like the most likely person to offer a trenchant critique of capitalism. But in a letter in 2020, and in a recent interview with The Free Press, that’s exactly what he did. Thiel identifies real estate as the weak link in a “generational compact” that’s failing to pass down prosperity from the old to the young:

The rupture of the generational compact isn’t limited to student debt…I think you can reduce 80 percent of culture wars to questions of economics—like a libertarian or a Marxist would—and then you can reduce maybe 80 percent of economic questions to questions of real estate.

It’s extremely difficult these days for young people to become homeowners. If you have extremely strict zoning laws and restrictions on building more housing, it’s good for the boomers, whose properties keep going up in value, and terrible for the millennials. If you proletarianize the young people, you shouldn’t be surprised if they eventually become communist…

Younger generations are told that if they do the same things as the boomers did, things will work out well for them. But society has changed very drastically, and it doesn’t work in quite the same way. Housing is way more expensive. It’s much harder to get a house in a place like New York or Silicon Valley, or anywhere the economy is actually doing well and there are a lot of decent jobs.

Now, for what it’s worth, I disagree pretty strongly about the claim that “you can reduce 80 percent of culture wars to questions of economics”. There’s pretty strong evidence that many sociocultural issues — and many of the divisions in American society over the last decade — revolve around either conflicts of values or perceived conflicts between identity groups.

The economics of immigration, for example, change little over time, but sometimes many Americans see immigrants as a threat, while at other times they take a welcoming attitude. Across countries, too, attitudes toward immigration differ radically; it’s hard to imagine that these differences are all dollars and cents. Race relations abruptly crashed around 2013-14, even though the economy was doing OK by then.

There’s also evidence that media technologies can exert strong effects on public opinion; for the same economy, you could get very different politics depending on whether people are getting their news from CBS and ABC or from X and Reddit. You can always choose to believe that subtle, unobserved economic changes are behind every cultural shift and identity conflict, but it’s not a very parsimonious or useful explanation.

But that having been said, I do think Thiel might have a purpose when he says that culture wars are fundamentally economic, even if it isn’t strictly true. Cultural issues are hard to solve — differences in values are deep-rooted and often immune to persuasion, while identity conflicts can take on a life of their own. We just don’t have great toolkits for solving those sorts of problems. But we do have a lot more of an idea of how to give people more of what they want in the material sense. So you can argue that economics should be our primary focus, simply because we have greater agency in terms of fixing it. “God grant me the courage to change the things I can”, and so on.1

And Thiel is exactly right that if you’re going to address economic problems, real estate is probably the one you want to start with, especially if you’re trying to make things better for young people.

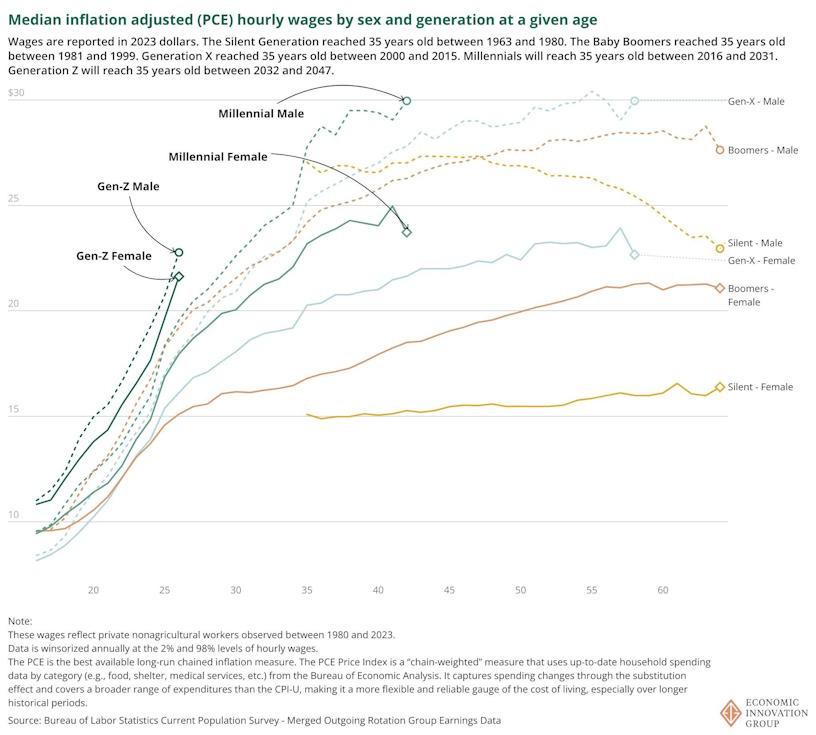

In many ways, the economy is working just fine for America’s young generations. For example, Zoomers and Millennial men have higher wages than previous generations did at similar ages, with Gen Z looking especially good:

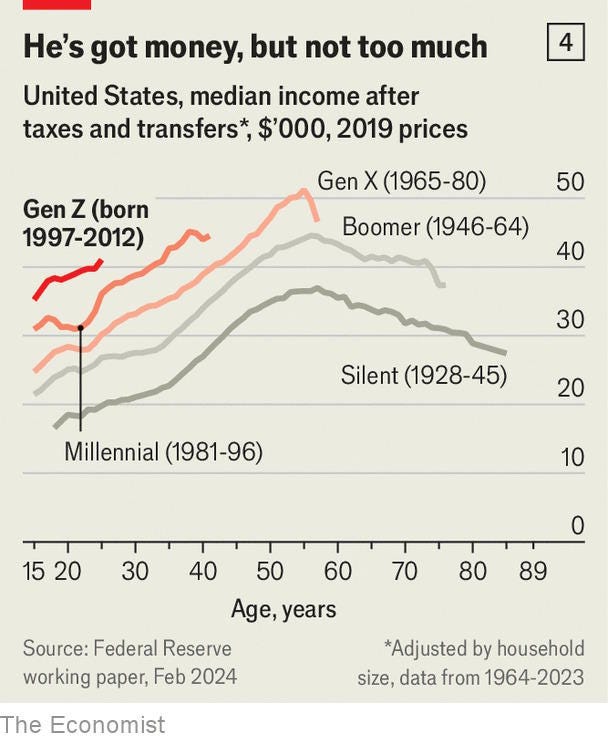

If you look at total income after taxes and transfers, each generation is doing better than the last:

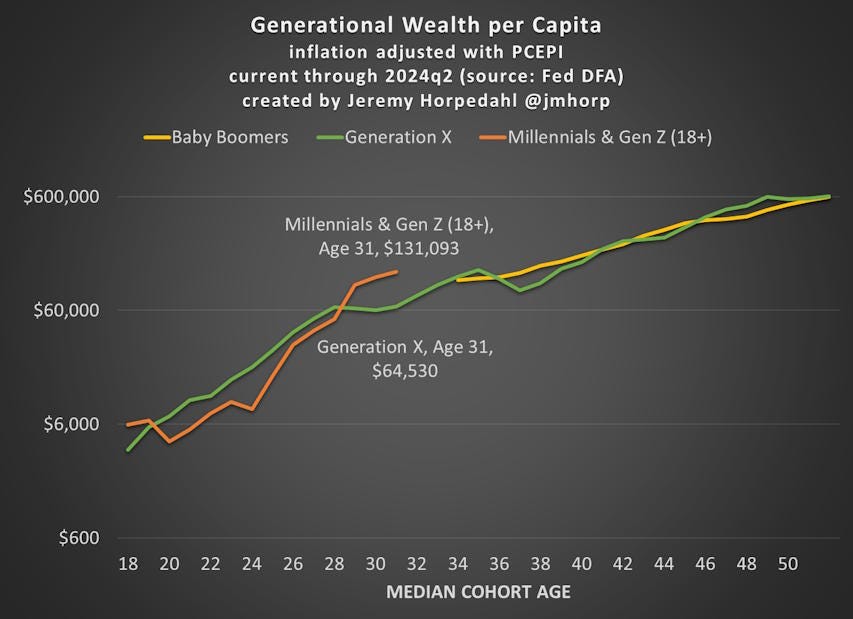

In terms of wealth, too, the younger generations are coming out ahead. By the time they reach 30, young people these days have more wealth than previous generations did, even after accounting for inflation:

And this is true across the distribution; poor Millennials have more wealth than poor Gen Xers or Boomers did, middle-class Millennials have more wealth than middle-class Gen Xers or Boomers did, and so on.

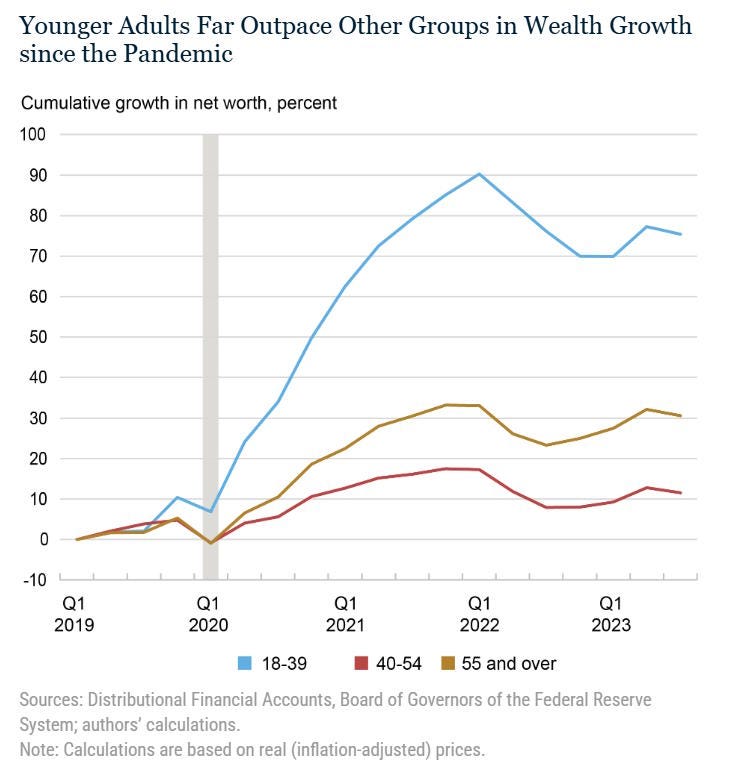

In fact, since the pandemic, young Americans have been building wealth far faster than older Americans!2

Now this doesn’t mean young people aren’t going to be mad about the economy. Social media has made it a lot easier to compare people’s lifestyles across income classes; seeing rich people brag about their fancy lives on TikTok may make inequality less tolerable than it was before. And sociocultural unrest — racial conflict, gender conflict, and so on — may seep into people’s perceptions of economic issues, so that material challenges feel more irritating.3

Those are perfectly respectable reasons to feel down about the economy. But they’re not necessarily something that policymakers can do much about, at least with the known tools of economic policymaking. Improving young people’s lives incrementally is doable, but allowing everyone to live the life of a TikTok influencer, or healing America’s cultural divides, is currently beyond the powers of any politician.

But housing is one area of economic life where the system really isn’t working for a significant portion of young people, and where the government could be doing a lot more than it is.