Heterodox vs. mainstream macroeconomics

If you're skeptical of one, you should be skeptical of the other too.

You don’t ever hear about “heterodox physics” and “mainstream physics”, do you? Or “heterodox biology” and “mainstream biology”. That just doesn’t exist. Why? It’s certainly not because physicists and biologists have the whole world figured out; there are plenty of unknowns and competing theories in those disciplines, and the fights in the seminar rooms can get downright vicious. Occasionally, both these disciplines are revolutionized by iconoclasts with bold new ideas. And yet you never hear that there’s a whole discipline of “heterodox biology” or “heterodox physics” shut outside the ivory tower, waiting for its day of triumph.

And yet you do hear about “heterodox economics” quite a lot. You hear about MMT, about the proponents of “greedflation” theories and price controls, and about the advocates of industrial policy. You might even hear about Austrian Economics or Post-Keynesian economics. There isn’t just one heterodox economics; there are many.

There are a few possible reasons why economics is different from other disciplines in having self-defined, self-contained heterodoxies. One possible reason is politics. Physics and biology are used to make technological tools, but economics is used to make policy; questions over how to distribute society’s resources will always be contaminated by the desires of interest groups and ideologies. It’s possible that mainstream economics is mainstream not because of its empirical merits or theoretical elegance, but because its precepts and its conclusions suit the desires of powerful interests. In fact, if you ask heterodox people, they will often tell you this is the case.

Of course to be fair, it’s also possible that politicized interest groups who want to subvert the dominant paradigm for their own benefit create trumped-up “heterodox” theories as a tool to gain influence. Mainstream economists are generally too polite to claim something like this out loud, but a few are probably thinking it.

But this is not the only possible reason that economics has formal heterodoxies. One thing you’ll notice is that all of these heterodoxies are about macroeconomics; they all deal with either the question of why national economies have recessions and busts, or why they grow and develop. You know, the really big questions. You don’t see a heterodox competitor to game theory, or tax economics, or labor econ — the smaller, quotidian questions of the day-to-day workings of the economy’s constituent parts. Heterodox people will tell you how to set interest rates, but not how to run an online auction. They’ll tell you how to grow your economy, but not how to set up a destination-based cash flow tax.

I suppose that there could be sociological or psychological reasons for this. Maybe heterodoxers have to go for only the big questions because their only hope is to attract public attention. Or maybe they’re just grandiose dreamers. But I think it’s something else; I think heterodoxers focus on macro because that’s where our greatest ignorance lies.

Last November I wrote a post called “Macroeconomics is still in its infancy”. Basically, our current mainstream theories of business cycles just aren’t that useful — they can’t forecast the economy, they have pieces that don’t work, many of the assumptions are fairly absurd, and nobody outside the discipline uses them. The theories missed the 2008 crisis and the Great Recession, and they can’t agree on the causes of the current inflation — in fact, I’d argue that after all these decades, economists still don’t have a good understanding of why inflation happens at all. Some of the most influential and decorated macroeconomists in the business have been known to go back and forth on the question of what causes recessions at all.

Almost none of these problems are due to nefariousness or stupidity on the part of macroeconomists; the issues are that A) macro data is just very sparse and full of dependencies, and B) a macroeconomy is a very complex thing, so building up a full model of it from micro bits and pieces is extremely hard to do. Of course these problems are only compounded for development theory, since development only happens once in each country.

In other words, macroeconomics is sort of in what Thomas Kuhn might call a “pre-paradigm” phase. Unlike in game theory or tax theory etc., humankind has not found the core of an approach that reliably explains key features of business cycles or growth policy. Heterodoxers go for macro because they’re competing to be the paradigm.

Neo-Brandeisian antitrust might seem like an exception to this rule, but it’s really not. In fact, the Neo-Brandeisians are a legal school of thought, not an economic one. The economic theories that explain various harms from excessive market power — such as monopsonies lowering wages — are very mainstream, and economists who are sympathetic to the Neo-Brandeisian cause tend to produce very mainstream-looking research in support of their ideas.

So anyway, I think there are probably both political, sociological, and scientific reasons why heterodox schools of economic thought are pretty much confined to macro. With that in mind, we can ask another question: How should we evaluate heterodox critiques and challenges?

In a recent thread, the writer Jeet Heer calls on mainstream macroeconomists to reflect on their own failings, rather than challenging the deserved “traction” of the heterodox:

But while I think it would be good for mainstream macroeconomists to focus on what they got wrong and try to rectify the situation, I don’t see any sense in embracing heterodox ideas simply because they’re an available alternative. Heterodox ideas deserve the same amount of skepticism and and continuous critical investigation that mainstream theories deserve. “The mainstream failed; we’re not the mainstream, hence we must be right” is a sort of a variant of the Politician’s Fallacy.

One problem in applying skepticism and critical investigation equally is that heterodox and mainstream theories use extremely different methodologies. Generally speaking, mainstream macro uses math, while heterodox macro uses literary text with no math. (There are a few exceptions, but that’s the basic pattern.) Which means that if we judge each theory using its own methodology, mainstream macro will have to pass rigorous quantitative evaluations, while heterodox ideas will “succeed” simply by humans vaguely and intuitively pattern-matching the conditions of the macroeconomy with the blocks of text they read.

It makes little sense for mainstream theories to have to forecast inflation and employment and growth to the nth decimal place in order to be considered useful, while heterodox theories are deemed a success simply because commentators waved their hands at the outside world and said “Sounds legit!”.

In fact, if we apply the “sounds legit” test to mainstream macroeconomics, it comes out looking pretty darn good as regards the recent inflation. Olivier Blanchard, using a simple mainstream Keynesian model of aggregate demand, managed to predict ahead of time that Covid relief spending would cause more inflation than most people realized. No heterodoxer I know of — certainly not the “greedflationers” — made such a bold, early, correct prediction. And a simple textbook model of aggregate supply and aggregate demand would also have predicted that the rise in oil prices in early 2022 due to the Ukraine War would pump up inflation even more.

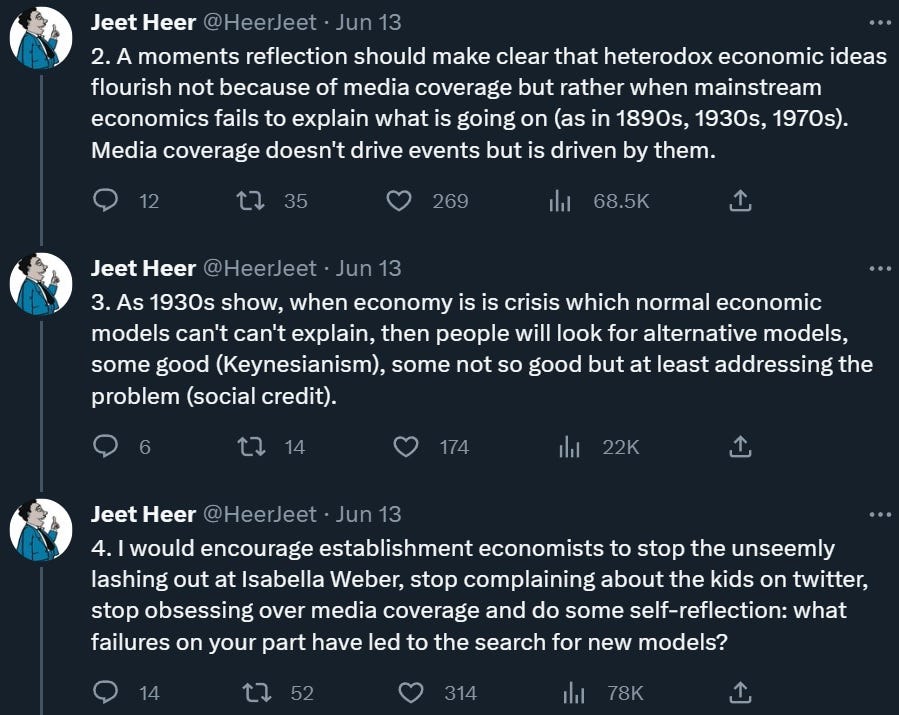

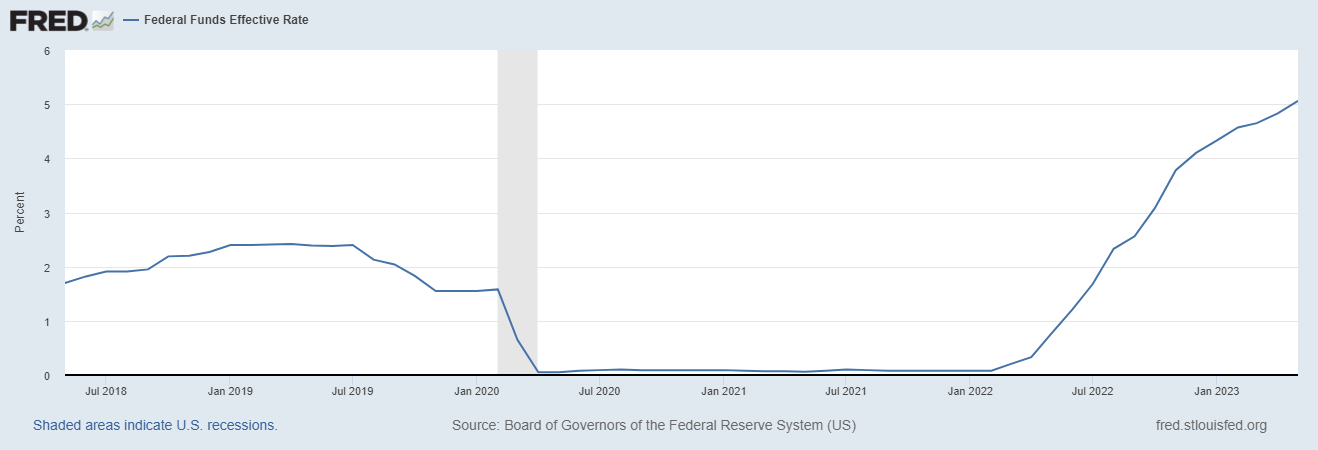

And mainstream macro also gave us most of the solutions to inflation. Mainstream theory says that in order to beat inflation, you raise interest rates and tighten up budget deficits. Well, we did both:

We also released oil from the Strategic Petroleum Reserve, a simple way to boost supply.

The only really “heterodox” thing America did to bring down inflation was to have the G-7 put a cap on the price of Russian oil. That might have weakened the market power of OPEC and sent oil prices lower. But in fact that price cap came after most of the big drop in oil prices had already occurred.

So while I think it’s a good long-term strategy, it’s doubtful the cap did much to bring down inflation in the short term.

Meanwhile, some combination of interest rate hikes, deficit reduction, and the fall in oil prices did the trick. Inflation isn’t yet down all the way to the long-term 2% target, but most measures show it returning to a fairly reasonable level:

And it did all this without causing a recession so far! The labor market has weakened only very slightly, and employment is still at near-record-setting levels:

A big reduction in inflation with no recession and no major rise in unemployment? That’s incredible! What more could you people want from mainstream macroeconomics?

As a result, the Fed is pausing its rate hikes — not declaring “mission accomplished”, since it’ll still keep rates elevated for a while, but at least declaring that the most dangerous and difficult part of the inflation fight is over.

To sum up: Mainstream macroeconomics correctly predicted the recent inflation, and gave us the tools that looked to have solved much of the problem. Heterodoxers, meanwhile, stood on the sidelines, calling for price controls that never happened and complaining into the void about corporate greed.

Of course, this general hand-waving, heuristic approach is how heterodox people judge their own success. By that method, mainstream macro comes out looking great in the current inflation. It’s only once you apply the mainstream’s own more rigorous critical evaluation and quantitative tests that mainstream theories start to look less spectacular.

For example, Blanchard may have predicted inflation, but he incorrectly predicted that it would manifest in higher wages rather than higher consumer prices. And most macroeconomists expected rate hikes to reduce inflation by raising unemployment; the fact that they haven’t so far is a big surprise, and the reason remains a mystery.

So I’m still somewhat unsatisfied with mainstream theory’s performance here. But when we do an apples-to-apples comparison against heterodox ideas like “greedflation” or MMT, the latter come out looking worse this time around. Critics of the mainstream, like Jeet Heer, ought to apply such apples-to-apples comparisons of success and failure, instead of insisting on holding the mainstream to astronomically higher standards.

I’m not trying to say that heterodox economics is full of crap, or that we don’t need it (although certain angry online people will doubtless interpret my statements that way regardless). In fact, I think that heterodox thinking helped improve the mainstream in the wake of the financial crisis, reintroducing ideas like the “Minsky Moment” back into the discourse. And I think that even now there’s a true revolution brewing in growth and development theory, with the heterodox idea of industrial policy starting to make a big comeback.

But what I am saying is that we should apply the same level of skepticism and criticism toward heterodox ideas that we apply to mainstream ones. To force mainstream theories to suffer the harsh tests of the ivory tower, while heterodox ideas are judged a “success” simply because a few credible journalists believe them enough to make cutesy videos about them, does a disservice to the pursuit of real understanding. And we desperately need to pursue real understanding as seriously and vigorously as we can, even if it’s really hard, because there’s a whole lot on the line — jobs, wages, incomes, livelihoods and lives themselves.

Great post as usual! As a current masters level student pursuing a "heterodox" econ degree in India, I wanted to share some of the things that I have observed in these circles. First, heterodox is insanely political by its very nature, to the point where serious, nuanced discussions can spiral down the drain very quickly. The sad part is that most of the absurdity stems from the students who have been made to believe that everything about modern econ is wrong and oppressive and blah blah (your usual marxist narrative). What ends up happening is that a typical heterodox econ class starts resembling a socio or an anthropology class, which is just tragic for reasons that are too long to list out. Second, ironically, heterodox cannot tolerate heterodox itself, because that would mean accepting the Austrians too, now show me a "Post-Keynesian" who is comfortable with that. Third, I would strongly disagree with you that heterodox deals mainly in texts as opposed to the mathematical mainstream, that is just not true. You have Kaldor, Kalecki, Sraffa and so many more who have gone beyond the usual constraints optimisation techniques and yet produced quite important theoretical work. I do agree though that some in the heterodox are unfairly against mathematical econ and therefore if one has to bet on which side will forego mathematical formalism first in a hypothethical world, it will be the heterodoxy, but still there is considerable mathematical work on both the sides. All in all, a serious form of reconciliation between the sides is needed, only then will Econ progress towards the true science it claims to be.

PS: Not too long ago on a talk of this exact topic, Arjun mentioned that you, Akerlof and him had a similar discussion on this very thing!

I generally agree, with the proviso that mainstream economics has survived by absorbing lots of ideas that were once heterodox, most notably Keynesian macro. The real problem is with self-conscious heterodoxy.

https://johnquiggin.com/2007/06/01/heterodoxy-is-not-my-doxy/