Great news about American wealth

Regular Americans are getting richer.

Americans have gotten used to reading a bunch of dire, grim news lately — war, inflation, political turmoil, etc. In this swirl of things to worry about, good news tends to fly under the radar. So your friendly neighborhood econ blogger, Yours Truly, is here to bring it above the radar…or whatever the metaphor is. Anyway, here’s some good news.

A week ago, the Fed and Treasury released its 2022 data from the Survey of Consumer Finances (SCF), which is a big survey they do every three years in which they ask households about their finances. Household surveys are important because they allow us to calculate things like medians — if you want to know how a household in the middle of the national income or wealth distribution is doing, you need to talk to a ton of households to find out what that distribution looks like. A downside of household surveys is that they take a long time to do (which is why the SCF only comes out every three years), so they don’t give you up-to-the-minute information. Another downside is that you have to be very careful about which households you survey, in order to get a representative sample. But even with those limitations, survey data is hugely informative.

Basically, the 2022 numbers — which you can see summarized in the Fed’s report — tell a really encouraging story. In a nutshell:

Americans’ wealth is way up since before the pandemic.

The increase is very even across the board, with people at the bottom of the distribution gaining proportionally more than people at the top.

Inequality is down, including racial inequality, educational inequality, urban-rural inequality, overall wealth inequality.

Debt is much less of a problem.

There’s even some surprising good news about income as well as wealth.

In other words, a rising tide is lifting all boats. I know it can be tough to believe that, with all the doom and gloom you see in the media, but the numbers speak for themselves. And just so you know, all the numbers I give in this post are adjusted for inflation, so don’t worry about that.

First, the good news

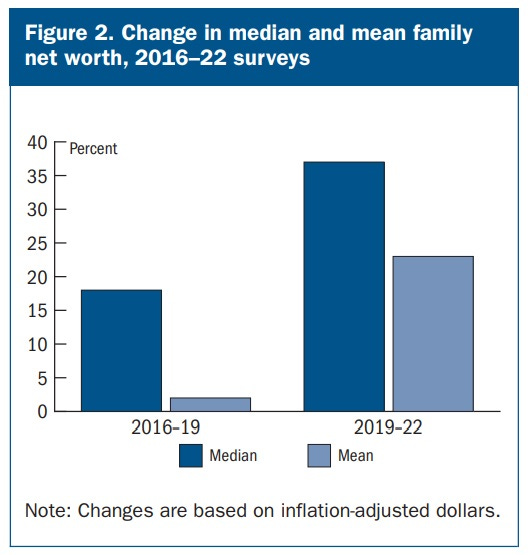

The biggest piece of good news is that the typical American family got about 37% richer between 2019 and 2022:

The fact that the dark blue bar increases by more than the light blue bar means that inequality went down. This was also true in the late 2010s, but wealth increased more slowly in those years. So the early 2020s have been quite a bonanza.

(Note that the SCF’s definition of “family” is actually very close to the Census Bureau’s definition of “household”, which is what you usually see quoted in these statistics. So while normally I wouldn’t use these terms interchangeably, here I will.)

This translates to an increase in wealth of about $51,800 for the median American household over three years. Not bad! Median family net worth is now about $192,900. This is much higher than Credit Suisse’s prediction, and would put the U.S. at 6th or 7th in the world.

Even more amazing is how even the increases have been — it really is all across the board. Here are just a few groups I picked out, but the number was positive for all groups in the report.

Not only did every group get richer, but inequality decreased across multiple lines — age gaps, racial gaps, educational gaps, urban-rural gaps, and overall inequality all narrowed over the last three years.

Two groups I didn’t include on the chart were households headed by people less than 35 years old, and people in the bottom 25% of the wealth distribution. The reason I didn’t include them is because they were so big — the increases were 143% and 900%, respectively.

900%? How is that even possible? The answer is that the people at the bottom half of the distribution had almost no net wealth to begin with. In 2019, the typical household in the bottom 25% had a net worth of only $400, which increased to $3500 in 2022. That’s still a very low level of wealth. But remember, it’s a net number — the people without much wealth in the U.S. often have a lot of debt, which cancels out the assets they own.

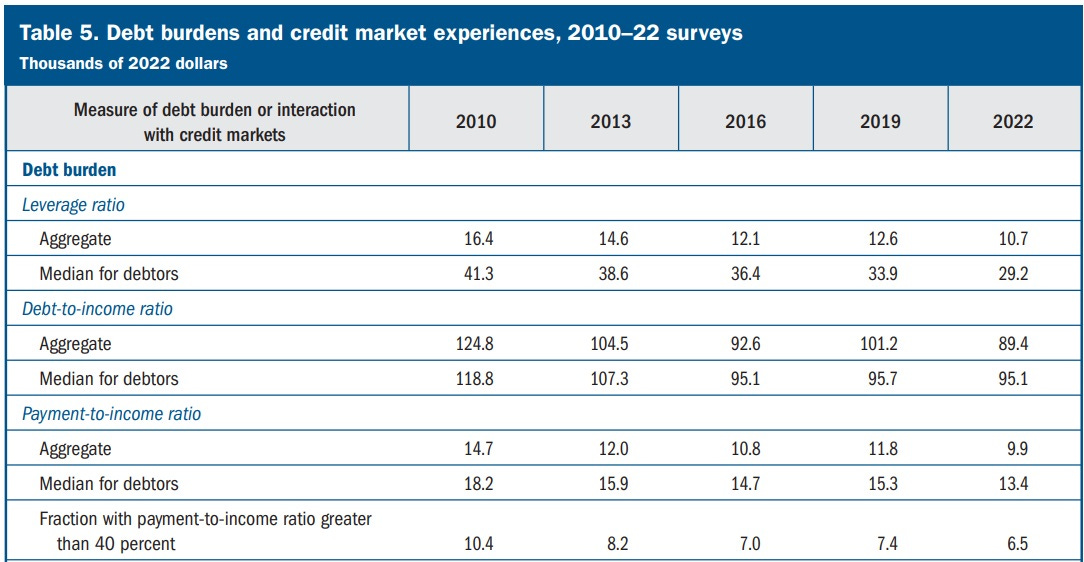

And a big reason that the wealth of the bottom 25% went up so much is that Americans are slowly getting out of debt. The debt-to-income ratio has fallen pretty steadily since 2010:

The money the government handed out during the pandemic probably helped with this — as I always said, that money was more about making Americans more financially secure than it was about stimulating the economy.

Falling debt wasn’t the only reason for rising net worth, though — lots of assets also went up by a lot in value:

Looking at this table, we can see that housing was, of course, a big one. That’s incredibly unsurprising. Most of the U.S. middle class’ wealth is in the value of their homes, so when housing prices go up, so will middle-class wealth.

Retirement accounts also did pretty well. Bond wealth increased by quite a bit — by about $70k for the median bond-owning household, which is surprising given that interest rates went up (which drives bond prices down). What must have happened was that Americans saved so much money that their bond holdings increased in spite of the rate hikes. Which means that if and when rates go back down, wealth will get pumped up even more.

(Side note: Whether bonds actually represent net wealth for society is a complicated question; someone is on the hook for that liability. But that’s a topic for another day; from the perspective of a household, a bond is wealth.)

In fact, the increase in wealth despite interest rate hikes is an incredibly good sign. Remember that the value of any asset depends in part on the discount rate, which is how much you’d rather have a dollar today vs. a dollar tomorrow. When interest rates go up, the discount rate goes up, which means assets are worth less. Remember the big stock crash in late 2021 and early 2022? That was probably driven by rate hikes. Higher rates also lower the value of bonds and — most importantly — houses.

And yet despite the fact that rates went from around 0% to over 4% over the course of 2022, wealth still went up. That means this wealth boom is very different from the increases in earlier decades, when rates were relentlessly lowered. Remember how for all those years we heard that the Fed was “inflating” or “propping up” stocks and houses and bonds by lowering rates and doing quantitative easing? Well, 2022 was the exact opposite of that. And yet the wealth gains didn’t stall out.

That’s a great sign for the future, because it means that if and when rates go down, Americans’ wealth will rise by even more. House price increases, in particular, are pretty clearly being driven by factors other than interest rates — the shift to remote work being the biggest driver, but also the Millennial generation finally buying homes.

Now, one slight note of caution. A bit of the increase in wealth — about $8300 for the median household — came from an increase in the value of used cars. A lot of people question how much of the value of a used car is actually wealth, because if you sell your car, you’ll either have to take the bus, which is a much slower and worse experience, or use some very expensive service like Uber. (This is much less of a concern for houses than cars, because if you sell your house you can rent a really nice house instead.) So if you don’t think a car is wealth, then the median household’s gains were a little lower than the number I quoted above. But the basic story doesn’t change.

Oh, and by the way, there’s one more piece of good news as well. The SCF doesn’t just ask people about wealth, it also asks them about income. The Census Bureau’s numbers, which are the ones you usually see quoted in the media, say that real median household income went down by about 4.7% between 2019 and 2022. But the SCF finds that it went up by about 3% over that time period. I’m not sure why the discrepancy exists (I’ll check on it and get back to you), but the SCF is a very broad, detailed, careful survey, so I tend to trust it a little bit more here.

So anyway, the basic story here appears to be that Americans saved a lot of money since 2019, and the value of their houses and retirement accounts went up in spite of rate hikes. That’s great news, and it suggests that much of the pessimism Americans are feeling about their finances is really more about the general unrest in American society and the scary stuff on the news.

But it’s also worth noting that rising wealth does leave out one important group of people — the folks who are looking to buy into the system.

The subtle challenge of broad-based wealth

There’s something subtle about the notion of broad-based financial wealth in a society. Most people think of assets — stocks, housing, bonds, etc. — as something that you make money from by selling it to someone else. But how can this work at the level of a whole society? If everyone has some of the same assets — if everyone has a Vanguard retirement account, a house, etc. — then who can they sell those assets to? How do you make money selling something that everyone already has?

In fact, there are some answers to that question. They can sell the assets to foreigners, or to young people who get born and grow up not having any assets. But the more fundamental answer here is that assets generally do have ways of getting you money even if you don’t sell them. This is called “fundamental value”. Stocks pay dividends, bonds pay interest, rental properties pay rent. Even a house that you live in gives you an income stream, though it’s harder to see — it’s the income you get to keep by not having to pay rent. That income stream is called “owner’s equivalent rent”, and it represents the fundamental value of owner-occupied housing.

This is important when we think about house prices and house affordability.

A lot of people point out that when house prices go up, it makes it more difficult for first-time homebuyers to afford houses. The Federal Reserve’s report makes this point as well, noting that the median home now costs 4.6 years of the median family’s income, compared to less than 3 years back in the late 90s.

This makes it harder for young people to buy into the whole housing system. Basically, they have to pledge more years of their future income — and come up with more cash as a down payment — in order to get a house today. Of course, mortgage rates around 8% make it even more difficult.

Now, that increased cost might be due to improved fundamental value. After all, houses are getting bigger and getting nicer amenities. Those improvements increase the amount that you’d be willing pay to rent the house, so they increase the amount you save by living in the house — thus, you’re paying more, but it’s because you’re getting more fundamental value. Houses can also become more valuable just from being located in the right city — if your town becomes a tech hub, the house represents a convenient place to find a job, and that makes it fundamentally more valuable (though ideally, this value should be taxed away and spent on public goods or returned to the public as cash…but that’s a story for another day).

So anyway, it’s possible to imagine a world in which reduced housing affordability isn’t a bad thing, because houses are getting better. But in the real world, there probably are some problems that result for reduced affordability.

First of all, young people looking to buy houses don’t necessarily have the liquidity — i.e., the down payment — to buy a house, especially in a pricey market like San Francisco. That can delay the day when young people get started building housing wealth, leading to generational frustration and low fertility rates.

Even worse, if housing becomes pricier because of artificial scarcity — NIMBYs using local government regulation and lawsuits to block new construction — then the total amount of value that the housing stock is providing is not actually increasing. In this case, older generations are actually forming a de facto cartel to overcharge young people for houses, forcing young people to sacrifice more years of their working life so that old people can live high on the hog. And making houses artificially scarce means there’s less housing to go around, which hurts the economy as a whole.

This is really the problem with using owner-occupied housing as the vehicle for a society’s broad-based middle-class wealth. If you manage nationwide housing prices and supply over time like Singapore does, then it can be OK, but that’s very tough to do. In the U.S., extracting more and more from the younger generations is often the quickest and easiest route to wealth for older middle-class homeowners. That’s why some people look at rising middle-class housing wealth with ambivalence or even trepidation.

But I’m not so worried this time around. First of all, young people who do buy in today stand to gain a lot — their wealth will soar if and when interest rates fall, and they’ll also be able to refinance their mortgages. This will be true even if a big nationwide push for new housing construction — the YIMBY movement you’ve heard so much about — manages to take the edge off of artificial housing scarcity.

In other words, the new SCF data has me feeling very optimistic about the state of Americans’ finances. I understand that the country is in a restless, divided state, and that there are scary things going on out there in the world. But the transition of most of the American population to a more secure financial footing is something to celebrate, regardless.

This sounds like bullshit to me, but perhaps I’m biased. Asides from myself, my entire family is what one might call “working poor” and just this week three people have called asking for help because they’re struggling. Two of them got promotions during the pandemic and one of them works as a train mechanic by day for Amtrak and had to pick up a second job in the evenings 3 nights a week to stay afloat. None of them have recreational drug habits, gambling addictions, or a penchant for spending money they don’t have aka crippling credit card debt. Sadly, not one of them can afford to purchase a modest home because every bit of their down payment savings dried up during the pandemic. My three person sample size is statistically irrelevant but I do have 43 cousins on my mom’s side alone nearly all of which have expressed similar misgivings in the family group chat.

> If you manage nationwide housing prices and supply over time like Singapore does, then it can be OK, but that’s very tough to do.

Worth noting in Singapore the rent's gone up enormously (40-80%) for many over the past couple years or so too. Marginal supply-demand imbalance and influx of new money can have disproportionate impacts that reverberate through the system.