Europe has to stand against Russia

The U.S. is going to get distracted, and Russia isn't going to stop.

Russia is not winning its war in Ukraine. But it has regained the initiative. A couple of months ago, in the wake of the victories in Kharkiv and Kherson, I was hearing talk of Ukraine mounting a winter offensive, and then a spring offensive. Now, all the talk is of Russian winter and spring offensives.

It’s always hard to know what’s going on in the fog of war, but here’s the general picture that’s being painted by experts like Michael Kofman and Phillips O’Brien. Initially, Russia invaded Ukraine with a huge number of armored vehicles but not many troops — perhaps only 120,000 or 150,000. Ukraine turned out to be very good at destroying Russian armored vehicles — the U.S. estimates that Russia has now lost about half of its total tank force, which is huge. But Russia mobilized a huge number of men — fewer than it would like, and none of whom are very well-trained, but enough to reverse its manpower shortage. Now Russia is generally believed to have about 300,000 troops in Ukraine, with perhaps 200,000 more on the way. That’s a lot of guys.

With fewer armored vehicles but a lot more soldiers, Russia’s tactics have shifted in a pretty predictable way. They are sending a bunch of infantry forward, supported by artillery barrages — sort of a modernized World War 1. They aren’t able to provide as much artillery fire as before, thanks to Ukraine’s HIMARS missile launchers disrupting their logistics, and due to old Soviet ammo stockpiles running low. But they still have a lot, and Ukraine hasn’t managed to destroy a large percent of the Russian artillery launchers. So between that, and a willingness to take very high casualties in what are essentially human wave attacks, Russia is wearing down Ukrainian defenses. The blunt fact is, although Ukraine’s army is more competent, Russia just has four times as many people as Ukraine, and if a much larger country mobilizes its whole society toward the task of defeating a much smaller (and poorer) one, it is very hard for the smaller, poorer country to prevail without sustained outside help.

Hopefully new Western aid packages that include Leopard tanks, longer-range glider missiles, etc. will turn the tide again. Hopefully Russia won’t be willing to continue to sustain massive casualties. Hopefully sanctions will weaken Russia’s economy to the point where it won’t be able to prosecute the war anymore. Hopefully.

But long-term security doesn’t run on hope; it runs on a sustainable balance of power. And in the long run, the United States can’t be counted on to be a permanent trump card against a Russia that has committed itself to an ideology and identity of expansion and imperialism. The only way Europe can ensure its own security is to unite and prepare itself to prevail in a long stand-off with the aggressive empire next door.

Russia is committed to imperialism in Europe

First, I think it’s important to emphasize just how unlikely it is that Russia will simply go back to the quiescent status quo power that it seemed to be back in the early 2000s, and which many Europeans still hoped it was right up until February 2022. The government’s New Years TV special trumpeting a new age of imperialism felt like something out of the 20th century:

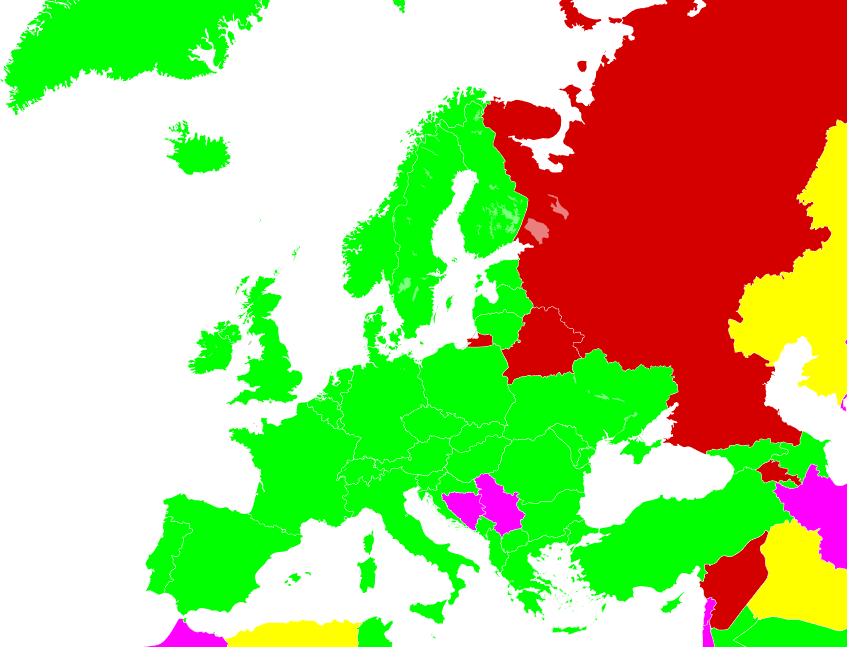

More generally, the evidence is clear that Russia’s new imperialists see their country’s mission as one of regaining control over territories it feels it lost when the Soviet Union fell — former USSR republics like Ukraine and the Baltics, former Warsaw Pact countries like Poland, and even parts of Germany. A number of Russian vehicles in Ukraine have the words “To Berlin!” painted on them.

Putin ally Ramzan Kadyrov has explicitly stated his desire to invade Poland, and Russia has threatened Poland with missile strikes. Baltic countries, whose intelligence services spend all of their time and effort monitoring Russian intentions, are quite afraid of an invasion, and Estonia has been repelling concerted Russian cyberattacks for decades.

It’s tempting to believe that these are just the hawks in Russia, and that there’s an opposition movement that will grow stronger as casualties mount. Perhaps that’s true, but there’s really no sign of a widespread or concerted opposition yet. And it seems just as likely that mass casualties of mobilized soldiers, along with sanctions, will embitter the Russian public against Ukraine and its supporters. As their children die and they become poorer, Russians may simply cling to Putin’s cheesy, throwback imperialism as the only organizing principle that gives their suffering meaning.

In any case, although it’s always possible that Russia will collapse into chaos or Putin will be deposed and his successors will be more interested in peace and stability, Europeans should be prepared for the very strong possibility that neither of these things occurs, and Russia spends the next two or three decades seeking to “expand”.

The U.S. is an unreliable partner against Russia

If Europe’s great enemy is likely to be relentless, its great ally is likely to be fickle and inconstant. The Ukraine War has shown that with the U.S. firmly on its side, even a poor, smallish country can effectively resist the Russians. The problem is that the U.S. is not likely to maintain its current level of support forever.

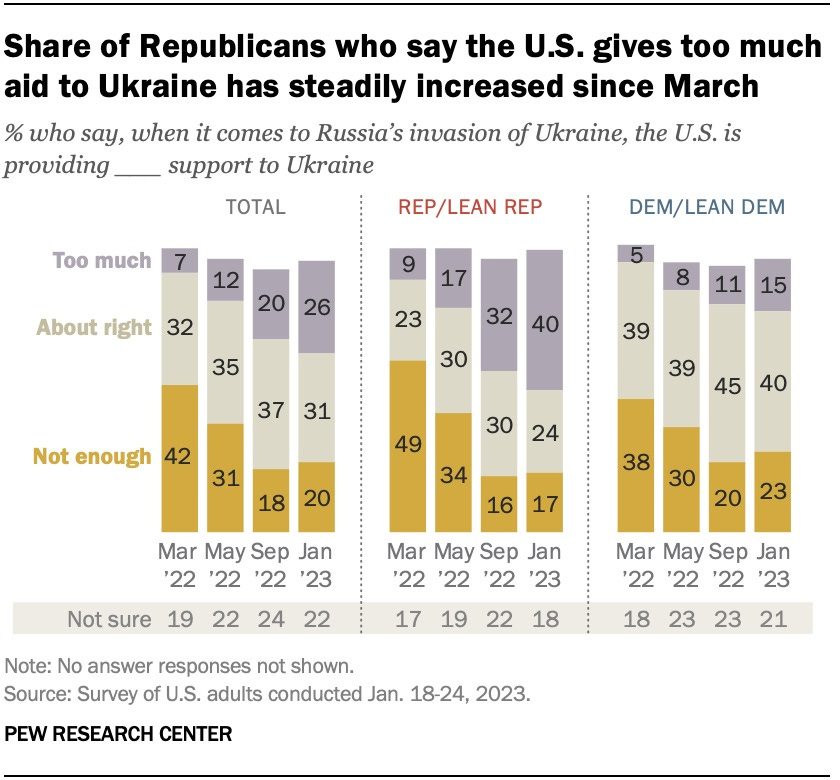

First of all, the U.S. remains a society deeply divided along political and cultural lines. “Negative partisanship” — the hatred of anything that’s perceived as being aligned or associated with the opposing party — is the Rosetta Stone that outsiders should use to understand America’s political culture. When Russia first invaded, support for Ukraine was strongly bipartisan. But in the year since then, relentless anti-Ukraine messaging by right-wing media figures like Tucker Carlson has taken its toll:

A few Republicans like Tom Cotton have tried to outflank Biden on the pro-Ukraine side, by claiming Biden hasn’t done enough to support Ukraine, but this effort seems to be failing; support for Ukraine is becoming yet another culture-war wedge issue.

This may already having an effect on Ukraine’s war effort. Elon Musk recently blocked Ukraine from using Starlink for at least some drone strikes, and earlier refused a Ukrainian request to use Starlink in Crimea. European leaders should realize that many of the U.S. military’s capabilities actually rely on technologies owned by private contractors, and that these private contractors don’t always see eye to eye with the U.S. government on issues of war and foreign affairs. Nor is this a new development; books like Freedom’s Forge document Henry Ford’s initial refusal to allow his company to participate in the Lend-Lease effort to supply the UK with weapons during the Battle of Britain.

Of course, the U.S. is not Ukraine’s treaty ally, but it is sworn to defend the Baltics, Poland, and the rest of NATO. But even this is not an ironclad security guarantee. Donald Trump wanted to withdraw the U.S. from NATO, and if he or an ideological fellow-traveler regains the presidency, that threat could become a reality.

But in fact there’s an even bigger reason why the U.S. can’t be relied upon to steadfastly defend Europe — its main geopolitical and security focus is in Asia, not Europe.

In the debate over aid to Ukraine, a number of voices in the foreign policy community have expressed a worry that the conflict in Europe is distracting the U.S. from the much bigger threat posed by China. Importantly, the people saying this are A) not isolationists or doves, and B) not partisan types. For example, here’s Jacob Helberg:

And here is Elbridge Colby:

And in keeping with these arguments, here is Hal Brands (whom I interviewed here and whose book I reviewed here), arguing for a short, sharp effort in Ukraine rather than a drawn-out one:

It’s undeniable, of course, that weakening Russia by helping Ukraine stymie their advance weakens China as well, by draining the resources of their most important ally. But this is a relatively minor effect; weakening Russia will not significantly degrade China’s ability to conquer Taiwan.

Arguments to refocus on China are likely to resonate with the American public, whose mass uproar over a Chinese spy balloon, compared with more blasé reactions toward Russian cyberattacks, shows that they perceive they perceive the latter as the U.S.’ most dangerous and most important opponent in Cold War 2. And they’re not wrong, either. In terms of both population and manufacturing might, China is a whale while Russia is a minnow.

Only in terms of nuclear weapons does Russia still hold any sort of an edge over China.

World War 2 again provides a precedent here. In the 1940s, Europe was a much more economically important region than East Asia. But in 1942 and 1943, the U.S.’ battle with Imperial Japan constantly distracted it from launching a “second front” against the Nazis. Churchill and Stalin were constantly exasperated that the U.S. concentrated its land forces on the Battle of Guadalcanal and its naval forces in the Pacific. Now, with Asia’s economic importance far greater than in WW2 and the U.S. facing a much more powerful opponent there, the U.S.’ tendency to look toward Asia and away from Europe is bound to be much larger.

In other words, the U.S. might keep helping Europe, but it might not. And even if it does keep helping, its assistance might be reduced due to a need to focus on China — especially in the event of an attack on Taiwan. Europe therefore cannot afford to continue to rely entirely on steadfast U.S. support to protect it from the Russian threat. It must unite and develop the ability to stop Russia all on its own.

Europe combined outmatches Russia

On paper, Europe combined is far more powerful than Russia. In terms of population, the Russian Federation is dwarfed by the EU and by the NATO countries other than the U.S.:

In terms of manufacturing output, it’s even more one-sided:

I added the UK here because it has been one of Ukraine’s staunchest defenders. Unlike the U.S., it’s not subject to the constant corrosive force of negative partisanship — conservative former prime minister Boris Johnson is aghast at Carlson’s support for Putin — and it’s not likely to refocus on East Asia either.

Nor is Europe economically dependent on Russia.

And the past year has shown that while cutoffs of Russian gas and oil can hurt European industry and European economies a bit, ultimately the impact has only been marginal. Europe made it through the winter just fine in defiance of all the apocalyptic predictions, and there’s no sign that Germany or other European countries are facing any sort of major de-industrialization. Despite all the hand-wringing, Europe’s economy grew in 2022:

And as time goes on, Europe will be able to adapt even more. It will import more oil from non-Russian countries, even as Russia sells its oil to China and India instead. It will import more liquefied natural gas, build more renewables, and hopefully build some nuclear as well.

Militarily, Europe will be able to outmatch Russia — if it tries to do so. The Ukraine war has shown that NATO’s military equipment, culture, and doctrine is superior to that of Russia. The only reason Russia looms so large as a military threat is that commits far more of its economy to its military than European countries do — even East European countries that are under immediate threat from Russia.

Europe’s unwillingness to provide for its own defense is why The Economist rightfully calls it “the free-rider continent”.

In order to stare down Russia over the next two or three decades, Europe must change this mindset completely. The invasion of Ukraine caused the region to unite politically around sanctions and military aid in a way that it hasn’t been united in its entire history. But this isn’t enough; Europe must unite to increase defense spending substantially, and wean itself entirely off of Russian energy.

Increased military spending in Europe will allow it to build up the masses of high-tech missiles, drones, satellites, and other weapons that will be necessary to defend it against any future Russian incursions without calling on assistance from the United States. It will also allow Europe to take over support for Ukraine’s war effort in 2024 and beyond, should partisan infighting and/or a pivot to China weaken U.S. gifts of aid.

To this end, Europe must also put aside petty internal squabbles. Brexit drove a deep wedge between the UK and the EU, especially France. Presenting a united front against Russia doesn’t mean forgetting about that disagreement, but the performative posturing and sniping over the dispute on both sides should be shelved.

Finally, Germany, as Europe’s top industrial power, has to refuse to let the well-justified guilt over its Nazi era prevent it from standing against Putin’s fascist conquests in the 21st century. The lesson of World War 2 should not be that Germany is an inherently evil or aggressive nation; it should be that fascism and imperialism need to be opposed by coalitions of nations wherever and whenever they crop up. With the caveat that reducing war and conflict to “good guys and bad guys” is always an oversimplification, it’s clear that Germany is playing for Team Good Guys now, and it should recognize and appreciate that truth.

In the 20th century, the free countries of Europe were too weak to stand on their own against a succession of totalitarian threats. The United States stepped in, stabilized the continent, and ultimately assisted in the creation of a Europe that was, in the words of former President George H.W. Bush, “whole and free”. But now that Europe needs to stand up and prove that it can defend the freedom it fought so hard to win.

As a subscriber, I am happy to see posts like this.

Thanks for the article, I think this needed to be said.

As a side-note:

"“Negative partisanship” — the hatred of anything that’s perceived as being aligned or associated with the opposing party —" As a European citizen, that's the impression I get about the USA, looking in from the outside.

If Biden had declared 'We have no dog in this fight' and ignored Ukraine's plea for military aid, the very Republican people who now decry that aid would have been the first to demand it and accuse Biden of abandoning the USA's most important allies (Europe) to their miserable fate. Conversely, if Trump had still been in office and done as Biden does now, Democrats would have accused him of war-mongering the world into WW3.

Any way you slice it...

Well, that's at least how it seems to me.