Eurocope

Pointing out America's problems will not help Europe solve its own.

I recently attended the excellent Kilkenomics festival in Kilkenny, Ireland. If you ever get the chance to go, I recommend it. Putting comedians and economists on the same stage doesn’t sound like it makes sense, but it’s surprisingly effective; they balance each other out quite well. And Ireland is a wonderful country, of course.

But I did notice one thing at the festival that made me a little sad. Since I’m American, the festival organizers stuck me on two panels about the United States — one about the economy, the other about Trump and politics. All throughout those panels, the comedians made jokes at America’s expense — how Americans don’t have health care, how everyone is poor, how guns and violence are everywhere, and so on. The crowd ate it up. But whereas in the past this would have felt like friendly teasing, now it felt strained and a little desperate.

Europeans have good reason to be mad at the United States right now. Donald Trump has scaled back U.S. aid to Ukraine, cut military aid to the Baltic states, expressed friendship and sympathy for Russia, and in general has done lots of things to indicate that the transatlantic alliance isn’t as firm as it used to be. Trump has slapped tariffs on Europe for no good reason, and has threatened much worse. And Trump’s vice president and other MAGA figures have demonstrated an unhealthy obsession with European immigration.

After all of that, it’s natural for Europeans to want to fire back. And compared to what Trump is doing, jokes about American health care and guns are pretty weak tea.

But at the same time, this catechism of America’s supposed problems often feels like a type of cope — a way that Europeans can avoid confronting their region’s own challenges by telling themselves that “Well, America is worse!”. In fact, I often encounter this same list of criticisms on Twitter, and in casual conversation with Europeans. It includes the following claims:

Americans don’t have health care

America is a poverty-ridden, deeply unequal country with no social safety net

American politics is dominated by rich plutocrats

Americans are uneducated

America is full of guns and violence

One problem with this litany is that most of it isn’t true; some of these problems were always exaggerated, and many of them have been effectively addressed since the 1990s. But a bigger problem is that these criticisms are deeply pointless. Even if all of these things were true, it wouldn’t reduce Europe’s need to address its own deep-seated set of problems.

America and Europe are actually very similar

On Twitter or other social media, commentary about national strengths and weaknesses almost always takes the form of head-to-head comparisons. The question isn’t “How can America and Europe solve their problems?”, it’s “Which is better, America or Europe?”. This rapidly becomes a zero-sum game, with each country’s partisans trying to win bragging rights by proving that the other is doing worse.

If you were starting from scratch and picking a system to emulate, this kind of head-to-head comparison might make sense. For example, in the Cold War, lots of newly decolonized countries had to pick which system to emulate, American-style capitalism or USSR-style communism.

But those days are over. First of all, almost every country on Earth already has its basic legal and institutional arrangements in place. But more fundamentally, there’s just not that much difference between the European and American systems. Both are basically capitalist economies, with fairly high levels of taxation, robust social safety nets, and fairly efficient public services.

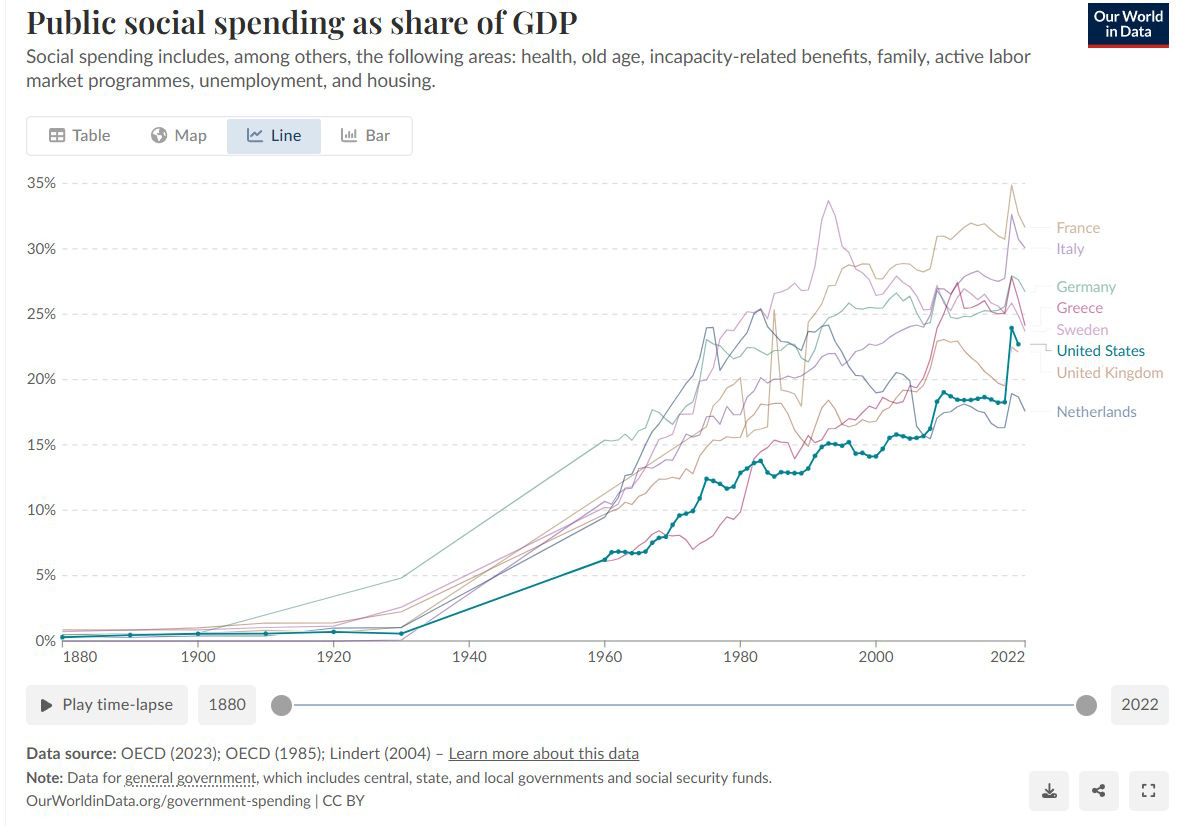

For example, a lot of people think America doesn’t do a lot of social spending. That’s wrong. The U.S. is similar on this scale to the Netherlands or the UK:

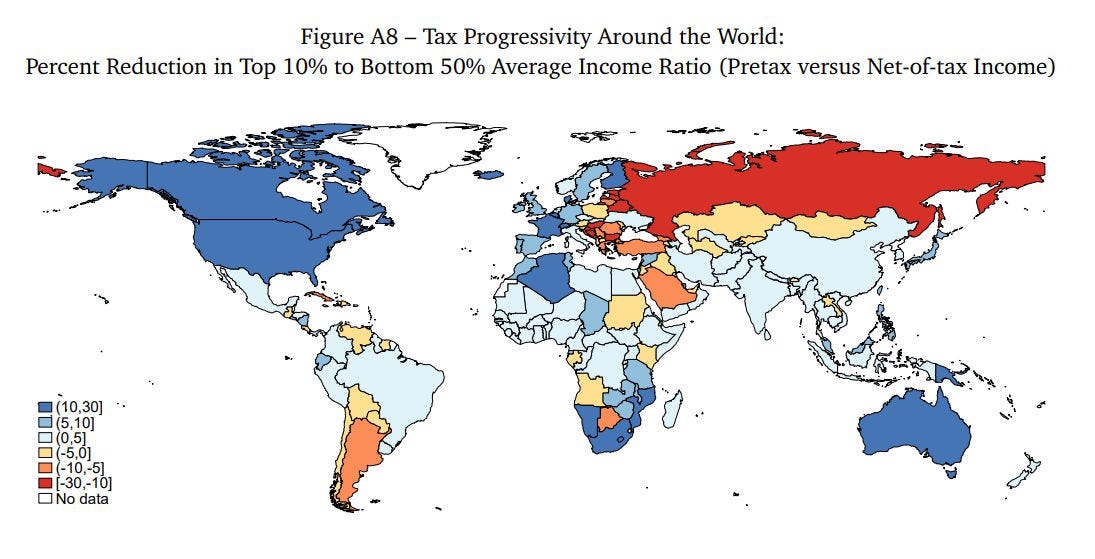

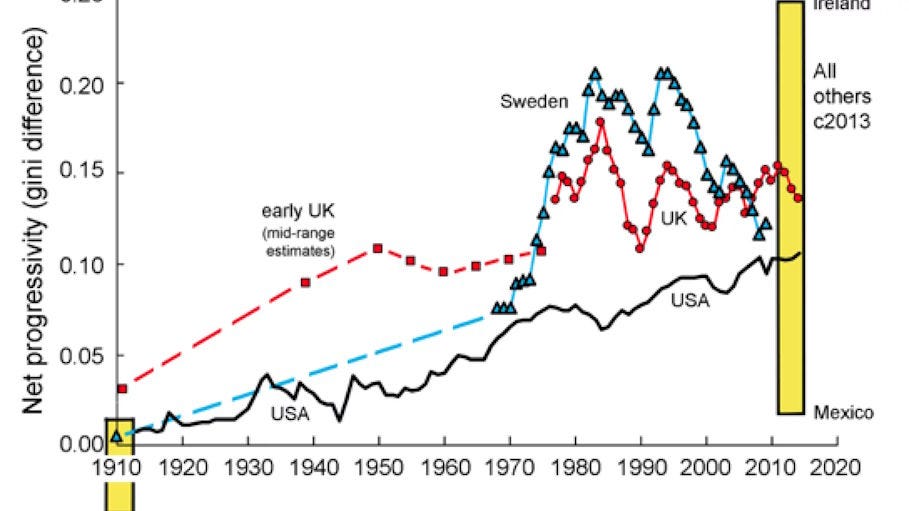

America’s fiscal system is also highly redistributive. Fisher-Post and Gethin (2025) estimated tax progressivity — the amount that the government’s tax and transfer system redistributes income — and they found that the U.S. is about as progressive as Europe:

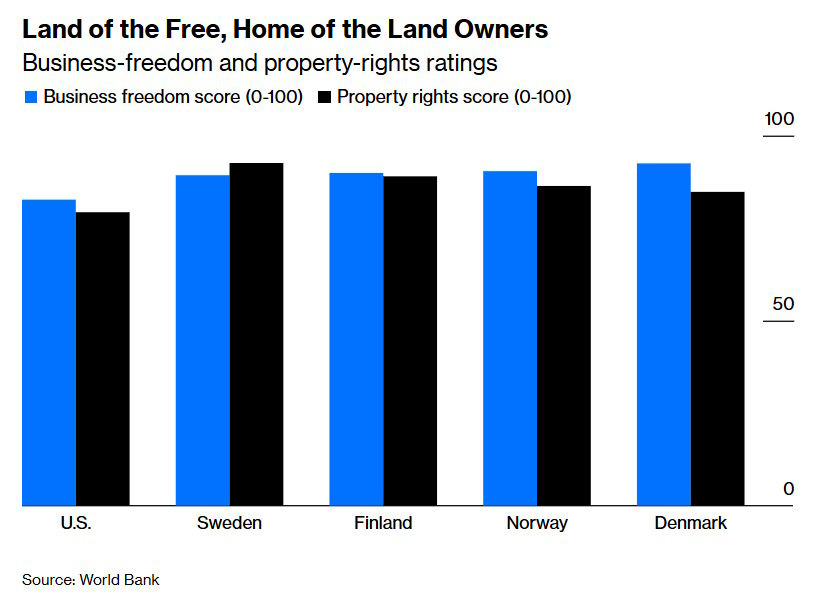

The U.S. also has a reputation for being a lot friendlier to business and capitalism than Europe. But measures of “economic freedom” tend to put the U.S. at about the same level as North European countries like Germany or Sweden. Here are some numbers from the World Bank in 2019:

And what differences do exist between the American and European systems are often due more to historical accident and institutional path-dependence than to any deep difference in philosophies about how economies ought to be run. European countries do not consider themselves “socialist”, as some Americans would like to believe. Nor are their governmental systems very different; many European countries have presidents.

I’m not saying Europe and America are exactly the same; there are some important differences, and we’ll talk about these in a bit. But the bigger point is that these are broadly similar systems; whether you chose to build your country on the “American model” or the “European model”, it would end up looking pretty similar.

Eurocope is deeply pointless

It’s not useless to contrast European policies and institutions with American ones. But thinking of Europe versus America in terms of a zero-sum competition is an activity with extremely limited utility, and plenty of downsides.

The most obvious point here is that even in the age of Trump, Europe and America are allies. If the U.S. does poorly, this will ultimately make Europe poorer and less secure. So when Europeans crow “Haha, look how bad America is!”, whether true or false, it’s what the kids call a “self-own” — they’re simply bragging about things about which they ought to be apprehensive. (Naturally this also applies to Americans who brag about “Europoors” and such.)

Even more fundamentally, pointing out America’s shortcomings — even if they’re real — doesn’t do anything to help Europe solve its own problems.

Every country and region in the world has challenges and shortcomings. Europe is no exception. Back in August, the Wall Street Journal had an article summarizing some of Europe’s woes, entitled “Europe is Losing”. Some key excerpts:

[T]oday Europe, particularly Western Europe, finds itself adrift, an aging continent slowly losing economic, military and diplomatic clout…The continent’s economies have been largely stagnant for about 15 years, likely the longest such streak since the Industrial Revolution, according to calculations by Deutsche Bank. Germany’s economy is 1% bigger than it was at the end of 2017, while the U.S. economy has grown 19%…Europe’s proportion of the global economy is now likely the lowest since the Middle Ages, according to the Maddison Project…

In the past 15 years, a key engine of European growth—manufactured exports—has been hobbled by events beyond its control, including U.S.-led trade wars, China’s mercantilist policies and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, which sent European energy prices skyrocketing…But Europe’s lack of economic dynamism has deeper roots, too. Taxes and regulations have risen inexorably; the volume of EU regulations has doubled since 2010. Sprawling rules protect old buildings, incumbent firms and aging consumers, limiting the creation of new infrastructure and industries…

Red tape in Britain is so bad that it took electricity firm Scottish Power 12 years to get permits for a high-voltage transmission line across Scotland. A project to build a new tunnel under the Thames river outside London has so far spent $340 million just on planning permits—documents that total 359,000 pages. Games Workshop, a fast-growing gaming company, is facing delays to build a new parking lot on its headquarters because a single bat lives there…

Energy is another problem. In Germany, industrial electricity costs three times as much as in the U.S.; in the U.K., four times as much. Britons now consume less electricity per person than the Chinese, and Germany’s overall electricity consumption is lower than it was before the Berlin Wall fell. Yet Germany has banned nuclear energy, and the U.K. has scrapped new offshore oil and gas exploration. Policymakers across Europe have laid out ambitious renewable energy plans…But the transition is proving painful…

Europe’s economic slide has been accompanied by shriveling military prowess. The continent’s share of the world’s military power is also at its lowest since the Middle Ages, after decades of focusing on welfare spending instead of defense. Though European leaders are now vowing to take defense more seriously in the face of a revanchist Russia, they are struggling to build up their forces.

Basically, Europe’s problems include:

Stagnating living standards

The Russian military threat

Expensive energy

Overregulation that makes it hard to build anything

Structural fiscal deficits

These problems tend to compound each other. Stagnating GDP makes it hard to fund Europe’s welfare states and pensions, and also to defend against Russia. Expensive energy makes European industry uncompetitive, which makes it hard for Europe to build the energy infrastructure that would bring costs down again. And so on.

On paper, Europe is committed to building green energy and electrifying its economy — both to power its industries and sustain its living standards, and also to fight climate change. But in practice, the region’s anti-development regulations and broken grid interconnection system are preventing the transition. The Financial Times reports:

Electrification has been stuck stubbornly at about 22 to 23 per cent of final energy use for more than five years, according to industry body Eurelectric. That’s roughly the same as the US but means that Europe has been rapidly overtaken by China, which is approaching a 30 per cent share…

Instead of abundant cheap, renewable power, energy costs are still between two and five times higher in Europe than in the US or China. European industry is flailing in response…

One of the main barriers to electrification in Europe is energy taxation…According to Eurostat, taxes on electricity have…increased faster than those on gas in recent years...Another challenge is the lack of incentive to improve the grids…The commission is working on new rules with the aim of speeding up permitting and grid connections (such is the backlog that in the Netherlands — often a canary in the coal mine for EU issues — some will only get grid connections in the mid-2030s)…[F]ragmented national concerns and slow efforts to rollout interconnectors between states have hindered progress [on a unified energy market]…Other challenges [include] the cost of solar installations, which are roughly four to six times higher in the EU than, say, Australia[.]

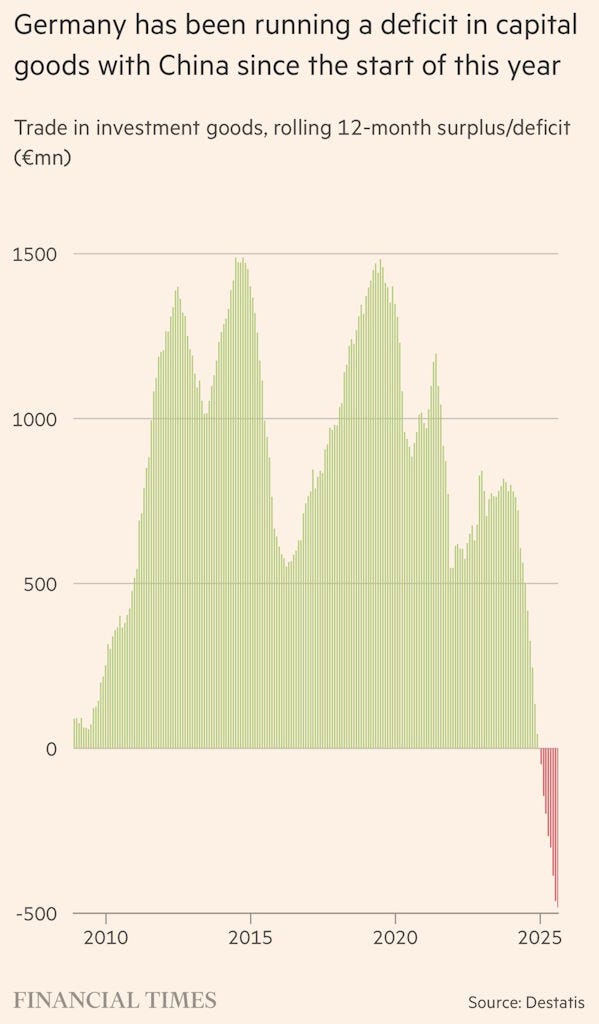

Europe’s expensive energy and overregulation have also made it completely incapable of meeting the competitive challenge from Chinese manufactured exports, which are beginning to hollow out Europe’s traditional industries. Germany used to make a bunch of money exporting industrial machinery to fuel China’s rapid industrialization; now, with Germany’s competitiveness imploding and China subsidizing its industries, the flow has reversed:

That’s only one example. There are many more:

Germany’s industrial backbone is facing an unprecedented challenge. Once the leader in high-end manufacturing, the country has witnessed a five-year decline in industrial production, which threatens up to 5.5 million jobs and 20% of gross domestic product (GDP), according to a recent report by the London-based Centre for European Reform (CER)…

The speed at which China has caught up with Germany is perhaps most evident in the auto industry. German carmakers have been criticized for a lack of innovation, a slow transition to electric vehicles (EVs) and not predicting fierce competition from Chinese brands like SAIC Motor and BYD. Those issues have led to threats of tens of thousands of layoffs and domestic plant closures…

Chinese chemical giants, for example, have significantly increased their output in recent years…[driving] down the profit margins of German producers like BASF…Even in the European Union…China grew its share of chemicals exports in the decade to 2023 by 60%, while Germany’s share fell by more than 14%…

Germany’s mechanical engineering sector…is also facing stiff competition from Chinese rivals. While Germany’s market share of industrial machinery exports declined slightly to 15.2% from 2013 to 2023, China’s share grew by more than half (from 14.3% to 22.1%).

If Germany can no longer compete with Chinese industry, what hope does the rest of Europe have?

This is all the more frustrating because China is vanquishing Europe in industries in which Europe should have a fundamental comparative advantage. Europe’s long-standing and deep concern for the climate, and its determination to switch to green energy, should make it a leader in producing batteries, solar panels, and electric vehicles — except China reigns supreme in all three industries, and Europe is primarily a consumer, writing China IOUs in exchange for shipments of green technology.

Bashing America will not help Europe solve any of these issues. Pointing out the fact that America has higher inequality than Europe will not help Germany build a single electric car. Decrying U.S. gun violence will not bring down British electricity prices by one penny. Taunting America over the chaos of its politics will not let France install a single air conditioner.

Focusing on these things will only serve as a distraction — a way for Europeans to rally a tiny scrap of civilization pride, even as the fundamental basis for that pride erodes out from under them. It is, in short, a cope. And it is not helpful.

And it’s especially unhelpful because there are some cases — not all, but a few — in which becoming a little more like America would actually help Europe solve some of its problems. No, putting guns on the streets and electing Trump-like leaders would not be a good idea. Privatizing health care wouldn’t be a good idea.

But in order to build new industries — battery and drone industries to fight Russia, an EV industry to be independent from China, a space industry to be independent of SpaceX — Europe will have to loosen its regulations around things like factory construction, mining, mineral refining, hiring and firing, and so on. That might exacerbate inequality at the top of society, because it would allow a few entrepreneurs to get very rich building these new industries. And it could lead to increased carbon emissions in the short term, before the green energy buildout gets big enough.

Those things would make Europe a little more like the U.S. in certain uncomfortable ways. If Europeans insist on continuing to buck up their spirits by painting a lurid picture of America as a plutocratic hyper-capitalist hellhole, it could make them avoid some very sensible and necessary policies.

So anyway, even if Eurocope were totally right about America, it would be counterproductive for Europeans to keep pointing the finger across the Atlantic whenever anyone suggests that Europe itself has grave challenges. But in addition, Eurocope is broadly wrong about America — or at least massively exaggerated in most areas.

Eurocope is out of date

My general sense is that Eurocope draws its mental image of America from the 1990s and 2000s — and especially from the Bush era, when tensions between Europe and the U.S. ran high over the Iraq War. But in the decades since Europeans formed their stereotypes of America, much has changed.

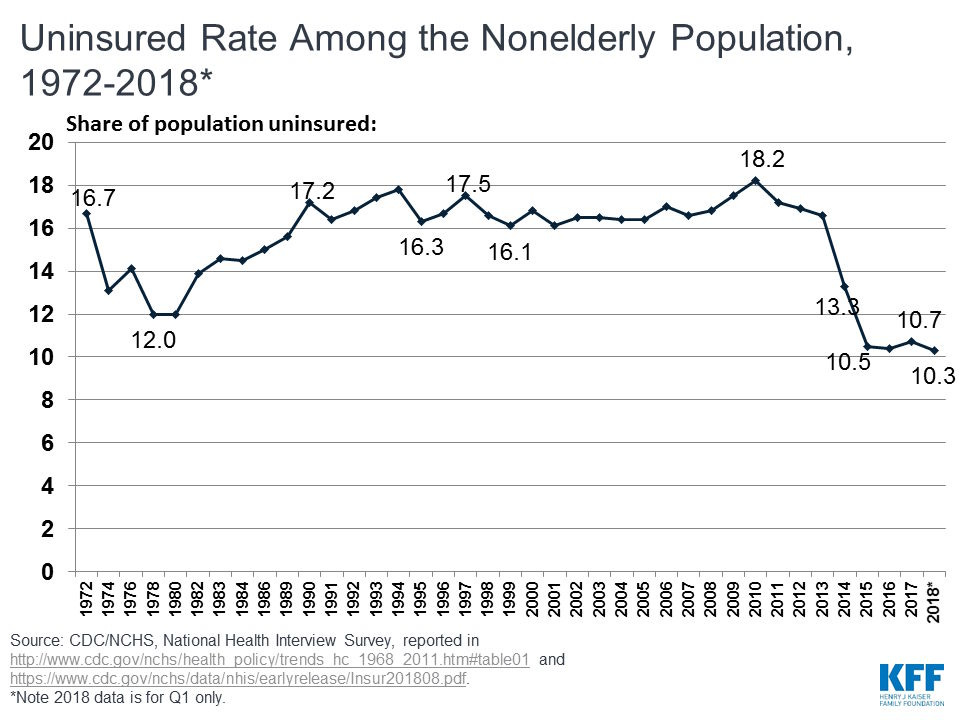

For one thing, most Americans now have health insurance. Elderly Americans were always covered by Medicare, but since the passage of the Affordable Care Act (Obamacare) in 2009, most other Americans have insurance too:

This improvement basically came from giving people a way to buy insurance that didn’t involve getting a corporate job.

And among the remaining uninsured, most are young people, who tend to need insurance much less. In other words, some percent of America’s remaining uninsured people are choosing to voluntarily forego insurance, despite universal availability and significant subsidies thanks to Obamacare.1

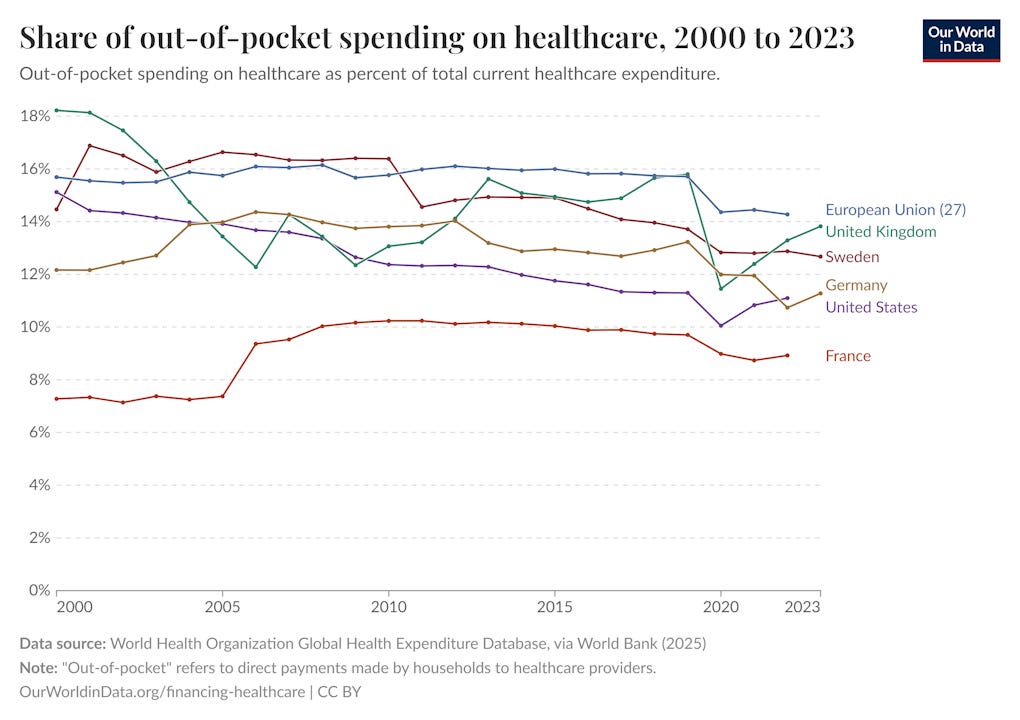

Nor are Americans paying a ton of out-of-pocket expenses for their health care. They used to, but thanks to policy changes, these days they no longer do. In fact, these days, Americans pay a lower percent of their health care costs than British or Swedish people:

The U.S. does have lower life expectancy than Europe, but this is primarily a function of obesity and drug/alcohol abuse; ironically, Americans’ higher purchasing power allows them to consume more unhealthy stuff that kills them. It is not a function of the relative quality of the American health care system.

To be clear, the U.S. health system is still worse than Europe’s in many regards. As the Commonwealth Fund’s international comparison shows, America ranks near the top in the quality of service, but lags badly in access, equity, and administrative efficiency. The U.S. has plenty more health reforms to do before its system rivals the best in the world on all fronts. But it’s simply not true that Americans “don’t have health care”.

As for America being a hyper-capitalist country that leaves its poor people to rot in the cold, that has not been true for a very long time. In recent years, America has gotten a lot less laissez-faire. With the shift of the tax burden to the rich, and the expansion of social services for the poor and working class — SNAP, various health care programs, the EITC and CTC, Section 8 housing assistance, and so on — America has become much more progressive since 1990. This is from a study by Lindert (2017):

In fact, some recent studies go farther. Blanchet et al. (2022) find:

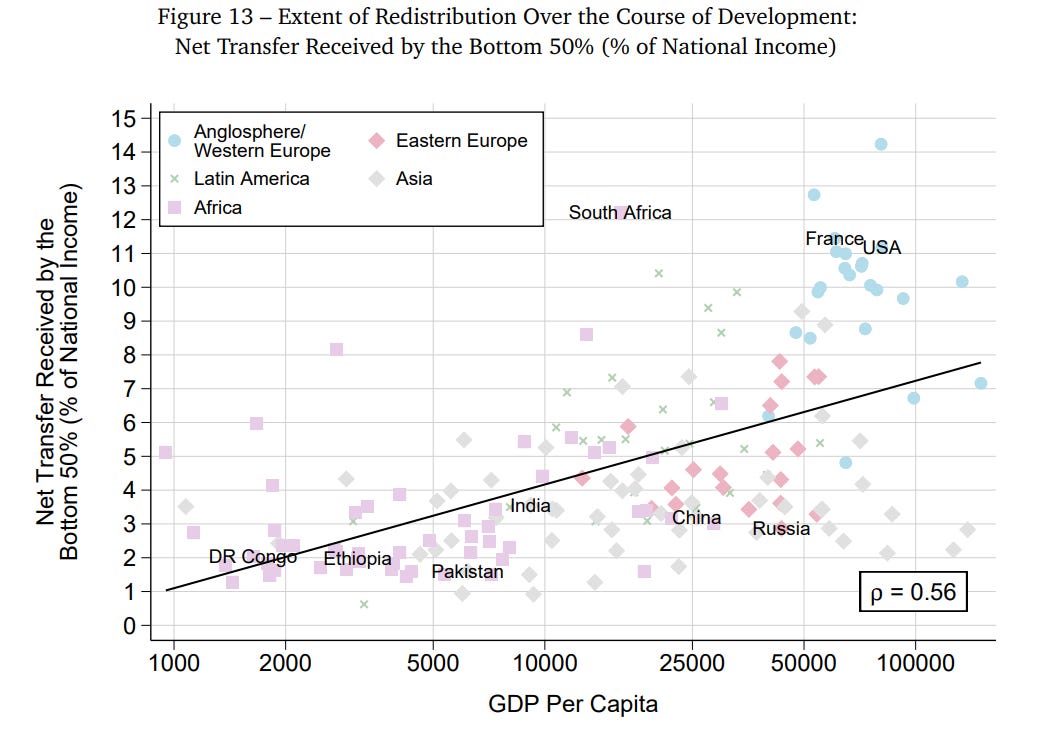

Contrary to a widespread view, we demonstrate that Europe’s lower inequality levels cannot be explained by more equalizing tax and transfer systems. After accounting for indirect taxes and in-kind transfers, the US redistributes a greater share of national income to low-income groups than any European country.

As you can see from the chart earlier in this post, America spends a lot more on social welfare than it used to. The reason America still has higher inequality than Europe is mostly due to “predistribution” — basically, pretax wage inequality — rather than a reduced willingness to provide for the poor or redistribute from the rich.

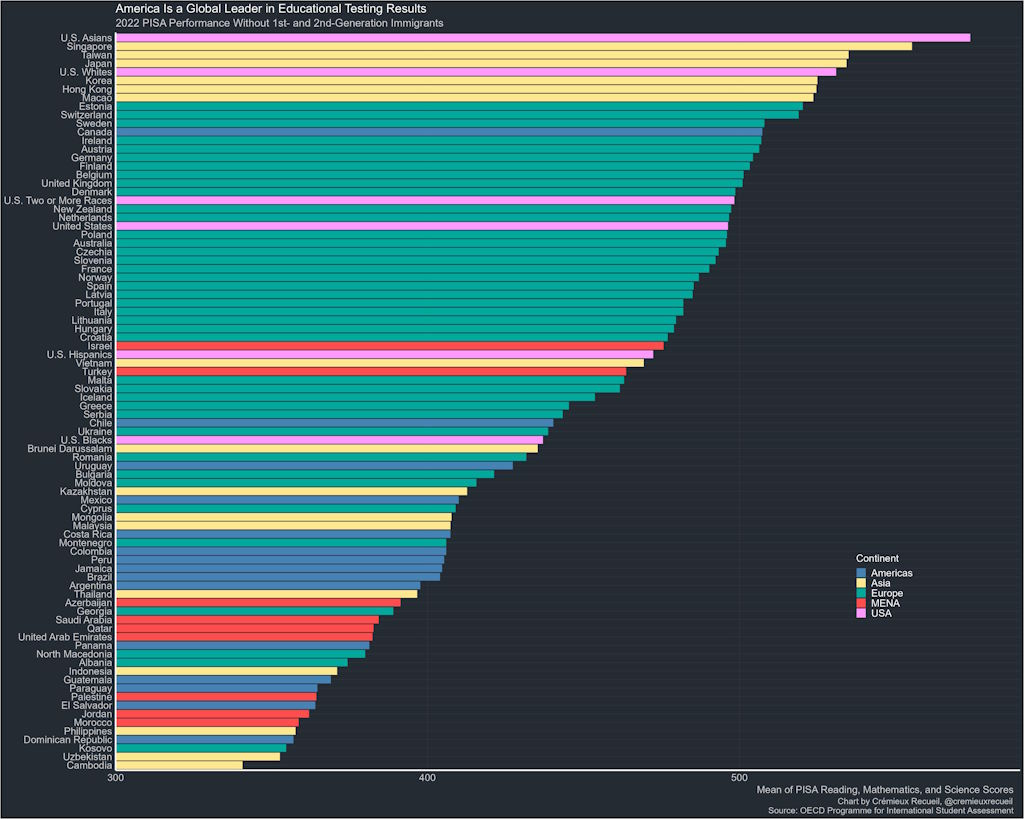

Other Eurocope tropes have never really been true. America’s education system takes a lot of flak, but on international comparisons Americans generally do just fine. On the PISA test — generally considered the best international test — White and Asian Americans clobber their European counterparts, while Hispanic Americans do about as well as Israelis and Black Americans do about as well as Romanians or Ukrainians:

That’s a picture of a very unequal education system, but overall a very effective one. Americans are not dumb.

Nor is the U.S. plutocratic oligarchy. That should be more than apparent from the way businesses have been impotent to stop Trump’s tariff rampage. But also, there’s evidence showing that middle-class Americans tend to get their way in politics (contrary to one high-profile study that got thrown around a lot in the 2010s but turned out to have serious flaws).

Not all Eurocope tropes are false, of course. America is a very violent, high-crime nation compared to European countries. The U.S. is much more unequal. Americans work more, and have much worse public transit.

But many of the standard Eurocope beliefs are simply no longer accurate. In the 1990s, 2000s, and 2010s, Americans realized we had problems with poverty and patchy health insurance, and we acted to address those problems — even though doing so was politically tortuous.

Europe would be well-advised to do the same. Countries are always more effective when they focus on self-improvement over comparisons with rivals. Europe has a lot of work to do in order to dig themselves out of their hole of economic stagnation and military weakness. It’s time to stop making excuses and get started.

In a true insurance system, this would cause a problem, because the exit of healthy people from the risk pool would raise premiums for everyone else until the system collapsed from adverse selection. Under Obamacare, however, government subsidies make up for reduced “subsidies” from healthy young people paying into the system. Health insurance isn’t really insurance in the traditional sense.

I think, from my time spent in Europe and from my European friends here in the States, that many Europeans feel the US is a bigger version of Europe that has betrayed them. After WWII they felt the US was their sort of big brother they could count on and now - that's gone away.

This view betrays a fundamental misunderstanding of the US. We are Americans, not Europeans. Yes, many of us are of European extraction but this country was founded in direct opposition to many of the bases of European thought - monarchy and theocracy amongst them. The founders detested so much about Europe and maybe that is now rising again in the US. I know I feel American even though my DNA is 99.7% European. I enjoy my visits to Europe but miss the US and feel our life here is in many ways far more satisfying than are those of many Europeans. I also deeply dislike, as Noah experienced, the lecturing and hectoring you hear from a certain class of Europeans and I don't think Americans, like our current VP, should be engaging in the reverse either.

It's definitely healthy that Europe is learning to stand on its own two feet. I don't think the US needed to bear the burden of Europe's defense for so many decades when Europeans were capable of bearing that cost themselves. And I also believe our security interests are for the most part deeply intertwined. But Europeans need to rid themselves of the smug, smarmy attitude Noah talks about in this piece. As he pointed out - it does no one any good, it's vastly out-of-date and it just makes them look like assholes.

Noah raises good points, but neither will bring condescending towards Britain (a pastime of Noah's) help fix America's problems.