Degrowth: We can't let it happen here!

We won't help the environment or the poor by valorizing poverty and decline.

A year and a half ago, I wrote a post entitled “People are realizing that degrowth is bad”. Around that time, the degrowth movement had started to receive a bit of attention in the U.S., as part of the general push for major action on climate change. But writers like Ezra Klein, Branko Milanovic, and Kelsey Piper spoke up and criticized the idea. In a nutshell:

Klein pointed out that major reductions in living standards would be politically unacceptable in rich countries.

Milanovic showed that meaningful global degrowth would have to go beyond rich countries; it would have to stop poor countries from escaping poverty, which would be both politically untenable and morally wrong.

Piper noted that coordinated global degrowth would take much more economic central planning than we’re actually able to do.

These were all correct and solid points, and together they probably spell doom for degrowth’s chances of gaining serious support either in the U.S. or in Asia, or in almost any other region of the globe.

But there is one region where degrowth has gained both intellectual respect and some measure of popularity, and that’s Europe, where the movement began. The European Parliament just hosted an event in Brussels called the Beyond Growth conference, at which Ursula von der Leyen, the European Commission President, gave a speech. The economist Nathan Lane live-tweeted the conference, and you can watch videos of the various presentations on YouTube if you like.

This doesn’t mean that I’m worried that the EU will embrace centralized planning to intentionally halt its growth or shrink its economy. In fact, as I’ll explain shortly, I think the degrowth people have managed to make their ideas amorphous enough where basically any step toward greater social democracy or concern for the environment can be branded as a “degrowth” policy.

But I do think the idea of degrowth could be corrosive to the European economy in a more subtle way. Because they’ve chosen to frame their ideas as being fundamentally about reducing GDP, the degrowthers are essentially making a virtue out of economic decline. And that enables and empowers a whole bunch of actors whose main goal is physical and social stasis — even if that stasis isn’t exactly what the degrowthers themselves would want.

So I suppose degrowth is an idea that has to be engaged with, for Europe’s sake if not for America’s. In my previous post I mostly just channeled the ideas of others, but this conference prompted me to dive a little bit more into the degrowth literature and rhetoric. Unsurprisingly, what I found there makes absolutely no sense at all, either as an academic project or as a plan for policy. Let’s dive in a bit and see why.

Degrowth is a mishmash of leftist rhetoric, pseudoscience, and occasional tidbits of actual science

A good resource for learning about degrowth is Timothée Parrique’s website. That website recommends two reviews of the degrowth literature: Kallis et al. (2018) and and Fitzpatrick et al. (2022). Looking at these papers, we can get a pretty decent idea of what’s going on here.

First let’s look at Kallis et al. From the abstract:

Scholars and activists mobilize increasingly the term degrowth when producing knowledge critical of the ideology and costs of growth-based development. Degrowth signals a radical political and economic reorganization leading to reduced resource and energy use. The degrowth hypothesis posits that such a trajectory of social transformation is necessary, desirable, and possible; the conditions of its realization require additional study...Here we review studies of economic stability in the absence of growth and of societies that have managed well without growth…This dynamic and productive research agenda asks inconvenient questions that sustainability sciences can no longer afford to ignore.

So the degrowth people tell us quite frankly up front that this is an activist agenda. It’s not about finding the truth; degrowth people have already found their truth, which is that degrowth is desirable and good. Having decided on their conclusion, they then proceeded to look around for research that supported that conclusion (or at least, that they felt seemed to support it). This is a polemical exercise, not an open-minded investigation into how the world actually works. There was zero chance that these folks would review the research and conclude “Uh, actually, I guess it turns out growth is good after all.” Therefore the studies the degrowth people cite are guaranteed to not just be cherry-picked, but also to be spun to support a narrative.

This intellectual project is intentionally grandiose. Here is the graphic that Kallis et al. include to illustrate all the topics and fields that they want to include:

This schema is both vast and vague; “role of energy and resources in the economy”, a topic that absorbs the efforts of vast numbers of researchers already, is but one subtopic in one box.

And yet when you look at who the degrowthers are citing, you see essentially no established researchers in these fields. Look at the paper’s list of works cited, and you’ll see journals like:

Environmental Values

Futures

Local Environment

Ecological Economics

Technological Forecasting and Social Change

Journal of Happiness Studies

Journal of Cleaner Production

Journal of Political Ecology

Finance and the Macroeconomics of Environmental Policies

…and so on. Fitzpatrick et al. (2022) will yield a similar list.

If you don’t recognize the names of any of these journals, there’s a reason for that. They are not only not top journals in the fields of economics, ecology, history, or sociology, they are not what any scholar in these fields would call respectable journals. They are obscure journals created by and for degrowthers and people in that general orbit.

You obviously don’t have to agree with mainstream economics or ecology or sociology. But if you’re going to criticize and try to overthrow these disciplines, you should at least engage with them; you should at least know what they say, so you can rebut it. And as soon as one comes in contact with degrowthers, it is immediately clear that they don’t have any idea what mainstream research says — at least, not with regards to economics. For example, the British anthropologist Jason Hickel is a prominent degrowth researcher and spokesman for the degrowth movement. Here is what Nathan Lane recorded Hickel claiming at the event in Brussels:

Now, I have been through an economics PhD program, and I have read a lot of economics papers, and no economist I have ever spoken to thinks what Hickel said, and that no economics paper I have ever seen has this as one of its conclusions. Hickel completely made this up.

If he knew the first thing about economics, Hickel would realize that the existence of an environmental externality implies that industries must not increase production every year regardless of how destructive it is. That is simply what it means to have an environmental externality. And if you do a quick Google search, you will find that top economics journals publish lots of papers and organize seminars on the topic of environmental externalities. Jason Hickel was not willing to do that 2-minute Google search, because he has made a conscious choice not to engage with the economics literature. Nor is it just Hickel; a quick perusal of the economics section in Kallis et al. (2018) reveals a number of citations, but none of modern mainstream economists or journals.

I don’t know the literature in ecology or sociology like I do econ. But the reference lists in the degrowth literature reviews suggests that the pattern is pervasive — degrowthers don’t really engage with the existing literature in any of the fields they intend to incorporate into their master schema. Instead they have attempted to do an end run around existing economics, ecology, history, and sociology, creating an alternative sphere of knowledge populated almost entirely by their own people. Within this sphere, the researchers — who are admitted to the club based on their shared acceptance of degrowth’s foregone conclusions — build up each other’s reputation by citing each other.

That web of citations also functions as a barrier to entry; anyone who tries to enter the degrowth-o-sphere has to hop from one degrowth paper to another, gleaning only tiny bits of additional understanding each time. Ultimately the only people who will be able to fully comprehend the idea package the degrowthers offer are the people who were willing to dedicate many many hours of their limited lifespan to reading a ton of the literature — i.e., either degrowthers themselves, or critics who are single-minded to the point of obsession.

(This sort of self-supporting intellectual canon represents a bit of a built-in exploit in the way that modern science works. Mainstream research fields do this sometimes as well — I could name some subfields of economics who do something along these lines — but that doesn’t make it good.)

Which is not to say that degrowth contains zero links to actual science, history, or economics. For example, a degrowther did point me to a paper by Steffen et al. (2015) in Science — reputable mainstream scientists in a very reputable mainstream journal. The paper basically argues that humanity is currently using too much nitrogen and phosphorus and causing too much biodiversity loss. Assuming the paper is a good one — and degrowthers would never link you to any critiques, even though they definitely exist — it is still only one tiny thread in the degrowth tapestry. What if we just…used less phosphorus and nitrogen, but kept on growing our economies? We’ve done that with plenty of other natural resources. Degrowthers will wave this idea away; as the infographic above demonstrates, “Green growth is unlikely” is one of their foregone conclusions.

That conclusion, by the way, is based on the thinnest of reeds. One of degrowthers’ central claims is that the decoupling of economic growth from environmental damage and resource use is impossible. Parrique has a long document explaining why he thinks this is the case, and it is similar to other degrowther critiques of decoupling that I’ve read. What they all share is a reliance on past trends to forecast future trends — decoupling has never happened, they say, so it won’t happen in the future.

That’s a complete fallacy, of course. Just because something is unprecedented doesn’t mean it’s impossible. You might as well say “A coordinated program of global degrowth is impossible because it has never been done before, case closed, degrowth is finished, you can all go home.” That would be unfair, and it’s equally unfair to say that just because growth hasn’t yet been decoupled from resource use, that it never will.

Except…it has. Take carbon emissions, probably the most threatening form of environmental damage. A great many countries have now decoupled the growth of their economies from the growth of their carbon emissions:

This is not relative decoupling (where environmental damage grows, but more slowly than GDP), nor is it merely per capita decoupling. It is absolute decoupling, where GDP grows and carbon emissions shrink. It’s also trade-adjusted — i.e. it’s not due to offshoring of emissions — so there’s no reason to think that this can’t happen on a global scale (indeed, global emissions may already have peaked, while global GDP growth continues).

Faced with this reality, degrowthers do a couple of things. First, they simply move the goalposts. After relative decoupling was accomplished, they claimed that absolute decoupling was impossible, based of course on historic trends. When it became clear that absolute decoupling was in fact happening, the degrowthers argued that OK, well, yes, it’s happening, but it can’t happen fast enough to save the planet.

And yes, it’s true that we haven’t yet decoupled enough to save the planet. The operative word here being “yet”. It should be apparent from even a moment’s consideration that decoupling of a sufficient sufficient to save the planet will not be evident in the historical data until the planet has already been saved. In other words, degrowthers will continue to insist that green growth is a fool’s errand until a number of years after that errand has already succeeded.

A second degrowther response is to lump in various kinds of resource use all together in order to obscure falling trends in the use of specific resources. For example, Jason Hickel and some other degrowthers will often use total tonnage of resource use as a measure of environmental impact. There are at least two obvious problems with this practice, besides the fact that it’s just one more case of assuming that historical trends are laws of the Universe. First, it’s scientifically incoherent. How do you measure climate change in terms of tons of resources used? How do you compare a ton of biodiversity loss with a ton of tin mined out of the ground? If you recycle a ton of wastewater, did you use another ton of resources? And so on. Second, using gross tonnage intentionally obscures one of the most important sources of green growth — the substitution of more common resources for scarcer resources.

In other words, this is very poor science indeed. And yet it’s on sweeping assertions like this that degrowth hangs its whole worldview; without tentpoles like “decoupling is impossible”, the whole edifice becomes merely a collection of disparate pieces of research about environmental harms. That would be more scientifically grounded, but it would probably not be the kind of thing you could organize a whole European Parliament meeting around.

Degrowth’s final tentpole is a blizzard of leftist, progressive, and social democratic rhetoric, all mashed together. For example, here is a quote from Fitzpatrick et al. (2022):

Degrowth is a multi-layered concept…It combines critiques of capitalism…colonialism…patriarchy…productivism…and utilitarianism…whilst envisioning more caring…just…convivial…happy…and democratic societies…Capturing the essence of degrowth is difficult because it carries at least three denotations…degrowth as decline of environmental pressures…degrowth as emancipation from certain ideologies deemed undesirable, like extractivism, neoliberalism, and consumerism; and...degrowth as a utopian destination, a society grounded in autonomy, sufficiency, and care.

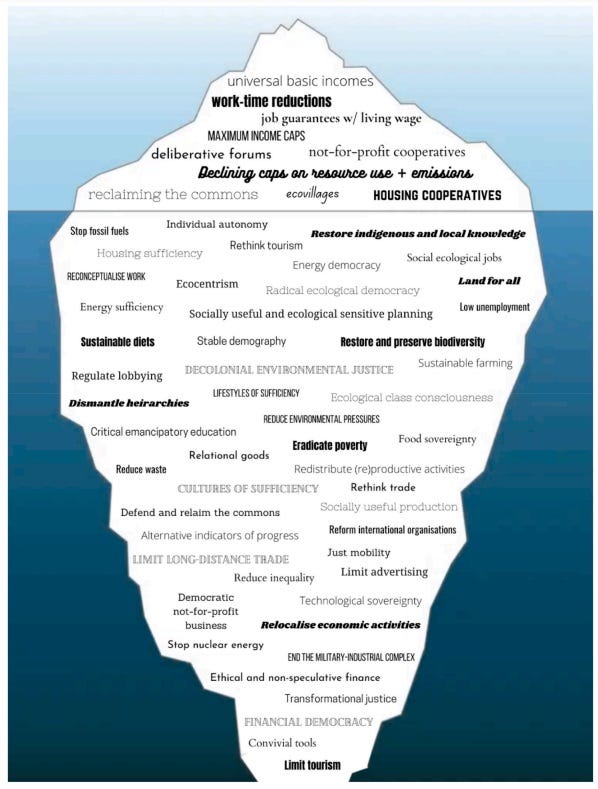

If that isn’t enough of a grab bag of buzzwords for you, consider the “iceberg model” from later in the paper:

Then there was the youth activist Anuna De Wever Van Der Heyden (yes, that is a real person’s name, it’s Belgium, just roll with it), whose closing speech at the European Parliament’s conference was about the need for “decolonization” as part of degrowth:

If you’re scratching your head and wondering “Wait, didn’t decolonization already happen in the 1960s?”, well, yes it did. But there’s this meme in some corners of the Left, especially in Europe, that capitalism is actually colonialism, so actually colonialism is still around. Yes it’s silly, but the point is that the degrowthers are trying to include every possible leftist cause in their rhetoric.

Degrowth’s ambition thus goes beyond the supplantation of economics, ecology, sociology, history, etc. — it also wants to become the central aggregator of every left-of-center utopian dream and every leftist ideology that has been kicking around the Western world since communism collapsed and forfeited that role three decades ago. It’s not just an activist project; it seeks to become the One Ring to Rule Them All of activist projects.

This dream is obviously far too ambitious to succeed. It is the kind of thing that can never really progress from the slide-presentation phase to global revolution; the various other activist movements will appreciate the name-check, but will be unlikely to bend the knee to the degrowthers as their ultimate leaders. And the thinness of the intellectual side of the project will warn most serious researchers to steer clear of the cause, or even to lob critiques at it, meaning that the idea will continue to be based primarily on catchphrases, infographics, and mutual citations of mutual citations. Even Eurocrats, who tend to love nothing more than a good infographic, are likely to balk when degrowth turns out not to contain much beyond a more strident restatement of all the same stuff that Green Party types already shout at them.

What degrowth looks like in practice

One of many reasons that I highly doubt that the degrowth movement will ever result in any actual degrowth is that many of their policy proposals are utopian leftist things that would require increased growth. For example, here are some more reports from the intrepid Nathan Lane on Jason Hickel’s policy proposals:

Many of these are good ideas, but all of them will require economic growth. Housing, green energy, public works, education, etc. are all types of economic activity, and they are counted in GDP; producing more of them will mean growth. Wages are income, and income is GDP, so raising wages will also require growth. Reading this laundry list of proposals for material abundance, I’m finding it hard to tell the difference between “degrowth” and Aaron Bastani’s idea of full automated luxury communism.

Hickel and other degrowthers argue that this bounty of new material wealth can be paid for by limiting the consumption of the rich — private jets, mansions, and so on. In fact, he makes a similar argument about the international situation, claiming that global degrowth can be accomplished even while allowing poor countries to get rich, simply by limiting the consumption of rich countries. Now he’s making an even more dramatic argument — that most people in the entire world can become much richer, and reduce economic growth enough to (supposedly) save the planet, simply by limiting the consumption of rich people in rich countries.

Now, Branko Milanovic has already debunked these numbers in terms of countries, so I won’t go through that again. And estimates that most of the environmental damage from rich-world consumption are due to the consumption of a few rich people are…well, frankly, they are made up. But Hickel and the degrowthers realize that actual degrowth is completely politically untenable, and so have instead chosen to claim that reducing economic growth will somehow result in houses and education and energy and good jobs and higher wages for all, through the magic of wealth redistribution.

And that’s fine. By changing the functional meaning of “degrowth” to something more akin to what Americans would call “democratic socialism” or “a Green New Deal”, the degrowthers have largely neutered the danger of their own project actually succeeding. There will be no program of coordinated top-down material impoverishment, because the degrowthers have realized that that would never fly, and have decided to ask for abundance instead. Good for them!

There’s just one problem. The rhetoric and idea of degrowth could seep into the popular European consciousness, giving regular folks one more reason to think that anything that increases GDP growth is bad. In practice, this would be things like housing, energy, and any other development project that would deliver the utopian era of abundance that the degrowthers now envision. In other words, no matter how many flights of fancy the degrowthers spout about how reducing GDP will somehow bring an era of plenty for everyone, actually existing degrowth is just going to be massive NIMBYism.

Britain, with its penchant for embracing bad economic ideas, and its intellectual class’ high level of interest in degrowth, seems especially vulnerable to this. Stian Westlake, the Chief Executive of the Royal Statistical Society and a longtime UK policy advisor, recently wrote an essay arguing that this is already happening. Some excerpts:

Fifteen years ago, when I worked in the “social innovation” field…everyone seemed to agree that economic growth needed to take a back seat, and that as the pursuit of GDP receded, it would make space for nobler things, like environmentalism and self-actualisation…So, a decade and a half later, how has this vision panned out?…

Well, the “abandoning economic growth” bit has gone surprisingly well. If you’re in the UK, you’re probably familiar with the ONS’s statistics showing what has happened to productivity—the UK’s output per hour worked—since the late 2000s. They make grim reading for economists, with growth close to zero, and far below the pre-2008 trend…But from a degrowth point of view, this looks like a success story…

[W]hy is it hard to decarbonise our energy systems? The rules against wind turbines and solar farms weren’t lobbied for by top-hatted capitalists, but by campaigners who think of themselves as protectors of England’s green and pleasant land: not BP and Shell, but the CPRE and the RSPB and countless local groups, and politicians seeking to accommodate them…

The same logic plays out when it comes to housing. If you accept the argument that Britain’s high housing costs have anything to do with our inability to build enough new housing to meet demand, you have to reckon with the fact that opposition to new building comes from people who for the most part claim to stand for protecting communities, protecting the countryside, and opposing “corporate greed”.

This sounds exactly like the kind of NIMBYism that afflicts the United States. But degrowth rhetoric, which is largely absent in the U.S., could give extra ammo to NIMBYs. Telling people that growth is bad is a way of valorizing national decline, stasis, and — ultimately — poverty. Folks like Parrique and Hickel might swear backwards and forwards that degrowth is (somehow) about enriching the poor, but in reality the idea that higher material standards of living are a bad thing is just going to lead to stuff like this:

Imaginary degrowth is you and your friends and everyone in Bangladesh getting a comfy life because somehow that’s what happens when we take away rich people’s private jets; actually existing degrowth is some old conservative British lady telling you that you don’t deserve a cheese sandwich.

I’ll pass on that, thanks. Europe should take a pass as well.

I've long been deeply concerned with the kind of exploit you mention in academia. To the extent it may happen in some subfields of econ and STEM fields is nothing compared to it's abuse in some softer areas of the humanities.

And it's not something that should be shrugged off lightly. Every professor employed in a non-productive field is using up resources that might be better used elsewhere. Worse, it exacerbates the problems of distrust of expertise since these fields often have the cachet of serious scholarship yet their results can't be trusted.

However, I've long struggled with how to successfully respond. When it's an area that's already embedded itself in the academy the response of: you obviously haven't read some obscure dense German treatise deeply so you don't have standing to critisize is really hard to overcome and it's so very easy to just label critics as Philistines or (if you lean towards the more STEM side of academics) as embodying the kind of arrogant 'everything but physics is dumb' attitude (prob worse if you're actually a physicist).

And at least degrowth is relatively closely connected to empirical claims that can be checked. Many disciplines also armor themselves against anything like that.

Any thoughts on a strategy? How do you kick a field of research that has effectively become an ideology not truth seeking from the academy? Internal criticism isn't enough if you'd have to waste 10 years studying bullshit to even just not be pushed out of the room much less listened to?

“There is no conceivable, stable scenario where the great preponderance of individuals, business interests, and governments choose to reduce wealth and productive capacity—to become poorer—voluntarily.” Paul Crider on degrowth: https://www.liberalcurrents.com/degrowth-neither-left-nor-right-but-backward/