Oxfam serves up a lot of dodgy statistics

Their numbers are more polemic than informative.

The other day, Representative Pramila Jayapal tweeted out some eye-popping numbers on wealth and poverty:

Now, taxing the rich and leveling the playing field sound well and good. But the numbers that Jayapal is throwing around here looked instantly suspicious. First of all, if a million Americans fell into poverty every 33 hours, the entire country would be impoverished in about one year. So it’s pretty obvious right from the start that these must be global numbers, not U.S.-specific numbers.

But even as a global number, one million falling into poverty every 33 hours is extremely fishy. It certainly isn’t any kind of long-term or stable trend. In fact, over the long term, poverty is trending strongly downward:

So where does this fishy number come from? As with so many eye-popping but ultimately specious statistics about global inequality, the answer is: Oxfam.

A British-based charity, Oxfam also releases various economic reports. The numbers quoted by Representative Jayapal are from the most recent of these reports, “Profiting From Pain”, released on May 23rd. Where do they get the “1 million every 33 hours” statistic? Well, they get it from another Oxfam report from April 12th, entitled “First Crisis, Then Catastrophe”. This report actually explains how they got their number:

Prior to the war in Ukraine and its spillover effects, the World Bank projected that COVID-19 would increase the numbers living in extreme poverty by 198 million people in 2022. The projected figures considered the impact of COVID-19 as well as an increase of inequality by 2%…On top of this COVID-19 poverty and inequality crisis, we now have an inflation crisis, with rapidly rising prices for food and fuel…Based on prior research done by the World Bank and Center for Global Development on food price spikes, Oxfam now estimates that another 65 million people could be pushed below the $1.90 extreme poverty line because of the harsh increases in food prices.

So they claim they took the World Bank’s prewar projection of 198 million falling into poverty in 2022, made a guess at how much food prices would rise, and then used a paper from 2011 to estimate an additional 65 million in poverty from higher food prices.

I’m going to assume that the Oxfam people correctly applied the model of Ivanic et. al (2011) — whatever that paper is, since Oxfam reports don’t actually seem to have bibliographies. I found an Ivanic & Martin (2008) and an Anderson, Ivanic & Martin (2014), but no Ivanic et al. (2011). But to be generous, I’m going to assume that this paper exists and that Oxfam applied its result correctly to their own prediction of rising food prices. (Update: The paper is here.)

Instead, I’m going to focus on the 198 million that the Oxfam people claim the World Bank forecasts to fall into poverty in 2022 — whether that number is right, and whether they should have added the 65 million to it. Spoiler: The answer to both is “no”.

First, did the World Bank really project that 198 million people will fall into poverty in 2022? I cannot find any citation or link to this supposed World Bank projection in the Oxfam report. Instead, all there is is a footnote, which refers to another footnote, which simply has some text claiming that the World Bank made this projection.

OK, so let’s check Google. 198 million is an uncommon enough number where I should be able to search for “poverty ‘198 million’ site:worldbank.org” and find the relevant document pretty quick. Right?

Except I can’t. There is no such document. The World Bank does not have anything published on its website issuing a projection of 198 million people falling into poverty in 2022. If anyone from Oxfam reads this and can furnish me with the source for the 198 million number, I would greatly appreciate it.

(Update: Oxfam replied, and their explanation is just as bad as you might expect. See the end of the post for more.)

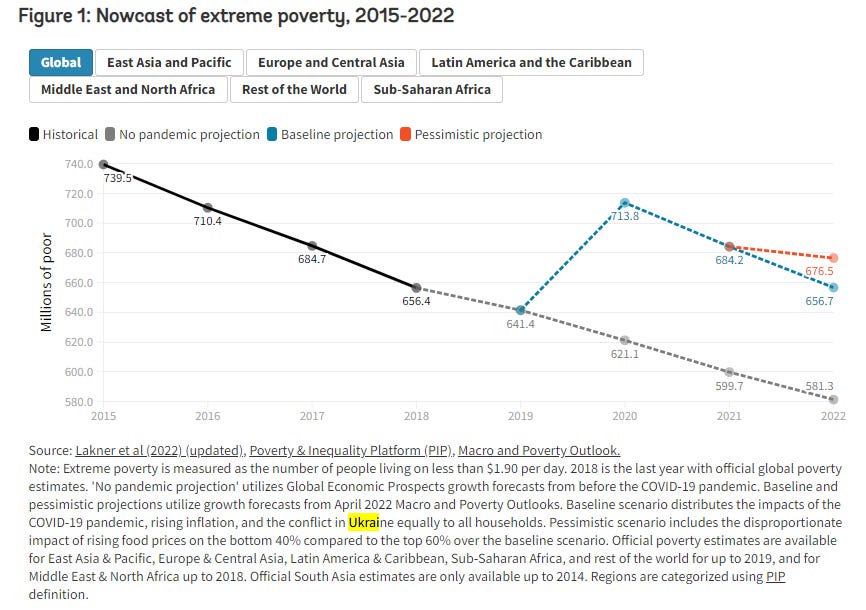

Anyway, after doing a few more Google searches, I DID find the World Bank’s actual projections of global poverty in 2022. You can find the projections at https://blogs.worldbank.org/opendata/pandemic-prices-and-poverty. Here is a picture of the World Bank’s projection:

I checked to make sure that this figure uses the same $1.90/day poverty threshold that Oxfam uses in its report. It does.

So, the first thing you’ll probably notice about this graph is that it projects that global poverty will go down in 2022, even under its “pessimistic projection” (the orange line). Not up by 198 million. Not up at all. Down, by 7.7 million.

Of course, the pandemic and war have raised the level of poverty relative to what it would have been if these events had never happened. The World Bank writes:

Figure 1 shows the global poverty trends under the baseline and pessimistic inflation scenarios. Under these two scenarios, the number of people living in extreme poverty in 2022 is expected to lie between 657 million and 676 million. Our projections prior to the start of the pandemic totaled 581 million poor people in 2022. This means that the COVID-19 crisis, growing inflationary pressures, and the Ukraine conflict will lead to an additional 75 million to 95 million people in poverty this year, compared to pre-pandemic projections.

Two big things to notice here. First of all, none of these numbers are anywhere close to 198 million. But even more importantly, the “75 to 95 million” number isn’t the number of people the World Bank expects to fall into poverty in 2022, it’s the difference between its total poverty projection for 2022 and its projected pre-pandemic trend.

As you can see on the graph above, all of the projected rise in poverty happens in 2020, after which poverty is projected to decline in both 2021 and 2022. Food inflation is predicted to slow the decline, but not to reverse it.

Now let’s talk about food inflation. Remember that Oxfam claims that the World Bank’s mysterious 198 million number doesn’t take the Ukraine war into account, which is why they then added the 65 million. But this World Bank projection is from April 13, 2022 — one day after the Oxfam report where these numbers come from! By April 13, the Ukraine war was well underway, and the World Bank was taking it into account:

To understand the changes in poverty since the beginning of the pandemic, we also predict poverty using growth forecasts available from before the pandemic as a counterfactual series. The difference between the actual and counterfactual series captures the effects of the pandemic—mostly for 2020—and then includes other factors such as the recovery (which was stronger than expected in some countries), inflationary pressures, and the conflict in Ukraine, especially for 2022.

In other words, the World Bank expects global extreme poverty to fall in 2022, even taking the Ukraine war into account. Not by as much as we’d like it to fall, obviously, but definitely not anywhere close to the 263 million increase that Oxfam claims.

So to sum up:

Oxfam pulled a 198 million number from who-knows-where.

Oxfam then added 65 million to account for the Ukraine war, even though the World Bank’s most recent projections already take the Ukraine war into account.

The World Bank’s most recent poverty projections show poverty going down in 2022, and being 75 to 95 million higher than if the pandemic had never happened.

Thus, unless someone from Oxfam comes through with a source for the 198 million number, and there’s some good reason to believe that number over the April 13th World Bank projections cited above, I must conclude that the poverty statistics Oxfam has been releasing to the media have no basis in fact.

(And of course the other number, for billionaires, is already out of date. The recent stock market crash will wipe quite a few of them from the ledger.)

Now, I don’t really blame Pramila Jayapal for getting taken in by this. I dare you to find me a public figure who has never carelessly linked to bad data. But Oxfam really should be a lot more careful about getting these numbers right before blasting them out to the world. And even worse, this isn’t the first time or the second time Oxfam has done something like this.

Oxfam is a serial repeat offender of dodgy statistics

Back in 2019, released some wealth numbers claiming that the bottom half of the world got 11% poorer, even as billionaires grew richer. I wrote a Bloomberg post explaining why these numbers were unreliable, which I summarized in a tweet thread. Some highlights:

Oxfam’s [wealth] numbers look dubious. If the wealth of half of the world’s people really fell by 11 percent in one year, as Oxfam says, it would signal the coming of an enormous global recession. But 2018 economic growth numbers look healthy — the International Monetary Fund estimates that almost every economy in the world grew last year, with only a small handful of exceptions. That suggests something funny is going on with Oxfam’s data…

Oxfam gets its wealth data from Credit Suisse, which provides yearly updates to its estimates. Comparing the 2017 wealth estimates to the 2018 updated estimates for 2017, we can get an idea of how much these numbers tend can vary…As you can see, sometimes these data revisions are small, but other times very large — for China, the difference is more than twofold!…If data revisions are regularly this big, then Oxfam’s assertion that wealth inequality went up substantially in 2018 could easily be illusory…

Wealth comparisons are always hard to do, but they’re even harder when comparing across countries. Big swings in exchange rates can dramatically change [wealth numbers].

Dylan Matthews of Vox followed up by contacting both Oxfam and Credit Suisse about the wealth numbers. He found that:

Oxfam had mysteriously mis-cited Credit Suisse’s numbers (the actual drop was 8.6%, not 11%).

About half of that drop was due to fluctuations in exchange rates.

Matthews notes that when the Financial Times’ Chris Giles looked into Oxfam wealth numbers in 2016, he found that exchange rates explained all of the annual change. And he also makes the very important point that the wealth of the global bottom 50% is very hard to measure; there are generally people in countries without good record-keeping or good markets to value assets like farmland.

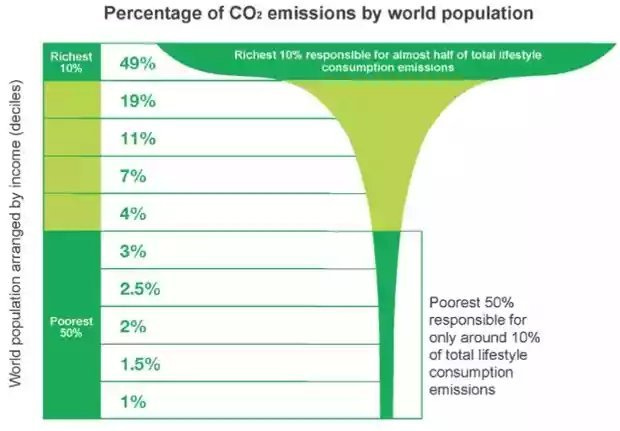

And then there’s Oxfam’s famous “funnel graph”, claiming to show that the richest tenth of the world population is responsible for most of the “lifestyle consumption” emissions:

First of all, note that the graph is flagrantly mislabeled. The estimates shown here are not “CO2 emissions”, as the graph’s title claims. Instead, these estimates are for “lifestyle consumption emissions”, which even in theory are only part of total CO2 emissions (total emissions also includes emissions from investment and government consumption). Of course, this mislabeling encouraged anyone and everyone in the media to misuse the graph.

Second of all, this data is from 2007; by the time Oxfam published the graph, poor countries had done a lot of growing; China’s consumption-based emissions, for example, had risen from 5.8 billion tons of CO2 to 8.7 billion.

Finally, the model used to estimate lifestyle consumption emissions relies on a lot of dodgy assumptions. Simo Raittila of Helsinki University wrote a Twitter thread laying out the assumptions that Oxfam uses:

The first and third of these assumptions are highly suspect. Income is not consumption; lower-income people consume a much higher fraction of their income than rich people do. That fact, which Oxfam ignores, will tend to make the distribution less lopsided. Also, rich and poor people’s consumption “baskets” look a lot different — for example, in a country like the U.S., poor people tend to spend a large fraction of their money on driving their cars, which is a very emissions-intensive activity. The global poor generally do not have cars, but you can see how the assumption that emissions = dollars of consumption might not hold.

So anyway, you can see that Oxfam very regularly serves up statistics based on highly questionable data and models, often in a sloppy and/or misleading way.

Perhaps the people who work at Oxfam think it’s fine to do this, because we all know that global inequality and global poverty are large, so exaggerating these ills in order to spur greater action is no great crime. Maybe they’re erring on the side of big numbers for dramatic effect. But if anyone is thinking this way, I strongly disagree. Global poverty and inequality are so big that the true numbers should suffice perfectly well for motivating people to action. The only thing that will come from willfully (or carelessly) putting out unreliable statistics will be to make observers eventually discount you as a credible source.

Update: Here is Oxfam’s reply, written in blog post form. They did not send it to me; instead, I had to find out about the reply’s existence from a friend. In any case, their explanation sheds more light on exactly how they got these numbers wrong.

First, the data source. The World Bank “projections” that Oxfam cites are, they claim, from an unreleased data set given to them by friends at the World Bank. In fact, the poverty numbers they claim are World Bank “projections” are in fact a single scenario that the World Bank models. Here is the table that Oxfam claims to have received from the World Bank:

Oxfam simply picks the worst-case post-Covid scenario, in which the global Gini coefficient increases by 2 points, and compares this to the pre-Covid scenario in which the global Gini didn’t increase at all. The difference between these two numbers is 198 million.

This confirms that Oxfam’s report and press releases misrepresent its data. They present 198 million as the number of people who are expected to fall into poverty in 2022 as a result of Covid. But in fact, this number is the difference between two projections for the entire pandemic period from 2020-2022. In other words, it’s still the case that most of this projected increase in poverty happened in 2020. It is not something that is happening now; it is something that already happened.

To get the actual number of people the World Bank predicts would fall into poverty in this scenario, we must compare the Bank’s projections for 2021 with its projections for 2022. Under the “2 percentage point increase in global Gini” scenario, the Bank projects 783 million poor people in 2021 and 795 million in 2022. This is an increase of 12 million in 2022, not 198 million! Even under Oxfam’s preferred (i.e. worst-case) scenario, the actual increase in poverty in 2022 is nowhere near what they claim.

Second, the World Bank’s projections from May (which take the Ukraine war into account) and what Oxfam claims are the Bank’s unreleased scenarios from March (which do not) are not very different. Certainly not by 65 million (the number Oxfam adds). But in fact, it turns out that Oxfam’s 65 million number comes from price rises that began before the war. They write:

Our figures on the impact of the food price spike result largely because we chose to make our estimates from when price foods began to rise, and not the beginning of the Ukraine war.

In other words, Oxfam is clearly double-counting the impact of rising food prices. They are taking prewar food price rises that were already taken into account in the World Bank’s March scenarios (and which mostly happened before 2022), and then counting the impact of those price rises a second time. This is clearly incorrect methodology.

In other words, Oxfam’s claim that 263 million people will fall into poverty in 2022 is not based on data. The claim should be retracted, and a more reasonable number issued. I do not, however, expect Oxfam to do this.

As if their bad stats are bad enough, I've never seen a SINGLE Oxfam report that discussed or took into account the benefits that arise from owning bunnies. Not one! Despite them being super cute.

As usual, ideological fanaticism results in big lies. Works that way whether one is left or right.