The above is a photo of the USS Washington, a World War 2 era battleship. The U.S. began building the Washington in 1938, before the beginning of the war, and well before the U.S. got involved. The ship had an advanced design for the time, including — crucially — some of the best radar systems in the world.

On the night of November 14th, 1942, Washington steamed into the waters around Guadalcanal, an island that was being fought over by the U.S. and Japan. For the U.S., holding Guadalcanal depended on maintaining an air force based at Henderson Field. The Imperial Japanese Navy had taken to bombarding the field with surface warships at night, which was rapidly degrading the U.S.’ air power. Due to Japan’s advanced torpedoes and superior skill at night fighting, the U.S. Navy had lost a lot of surface ships. So the U.S. admiral in charge in the region decided to gamble by sending his battleships into the fight.

To some, it seemed like battleships were already obsolete. They had proven incredibly vulnerable to air power, meaning that aircraft carriers now ruled the sea during the daytime. And battleships were also very vulnerable to torpedoes launched from smaller ships or submarines. Indeed, after World War 2, navies stopped building battleships entirely.

But on the night of November 14th-15th, 1942, the USS Washington proved herself incredibly useful. With most U.S. ships out of the fight, and the Japanese battleship Kirishima heading to bombard Henderson Field, it was Washington that saved the day. Commanded by Rear Admiral Willis Lee — a noted gunnery expert — Washington surprised and sank the Kirishima with radar targeted gunfire. Henderson Field was saved, the U.S. won the Guadalcanal campaign, and the Imperial Japanese Navy never really recovered.

Not bad for a soon-to-be-obsolete ship that we started building before there was even a war.

Which brings me to defense spending. Last week I wrote a post arguing against across-the-board defense budget cuts, and putting our current military budget — and Joe Biden’s small proposed increase — in perspective by comparing these to GDP and inflation. A week later, Matt Yglesias wrote a rebuttal in which he argued at length for a reduced defense budget. So this is my response. (It’s nice to be able to disagree with Matt about something, as people often think our perspectives are one and the same!)

The first question is how much we actually need to spend. Unfortunately, no one can really knows this for sure, and people who understand the nitty-gritty details of weapons technology and procurement will have a better understanding than either myself or Matt. But I think that there are some general principles at work here that Matt and others who call for defense cuts are largely missing, so I wanted to lay those out here. And I’m going to use the saga of the USS Washington as an object lesson.

How much do we need relative to Russia and China?

The Ukraine war and the Afghanistan pullout have made it clear what the purpose of our military spending will be in the years to come. Instead of building a military oriented around occupations and counterinsurgencies, our role will be to check the expansion of the totalitarian great powers — Russia and China. I’m not happy that totalitarian great powers are stalking the Earth once again, but I do think the U.S. is inherently much better suited to helping the world defend against such threats than to try to act like an empire.

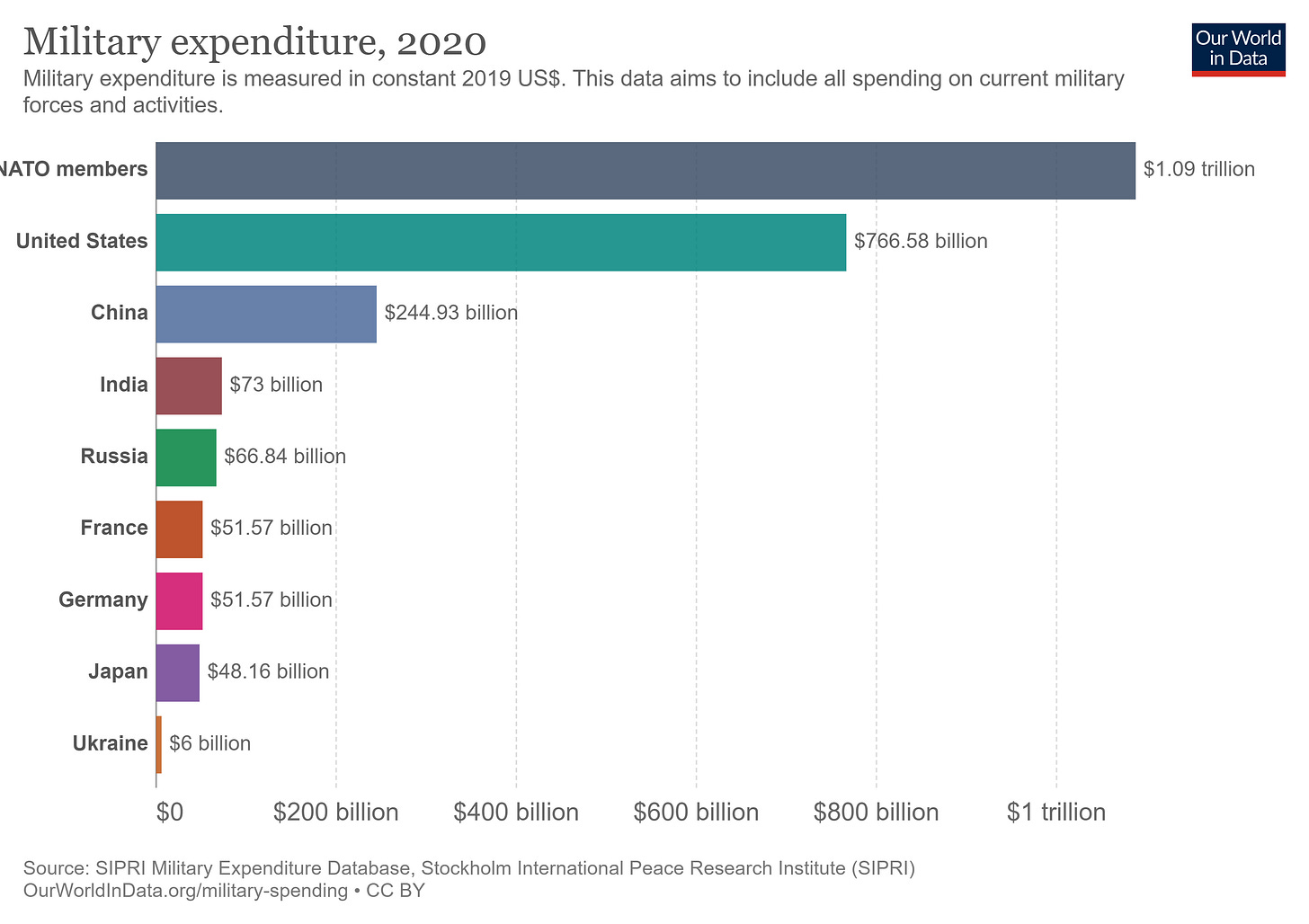

But how much should we spend in order to check Russia and China? Matt cites the fact that the U.S. spends more than twice as much in dollar terms as Russia and China combined. Add in the other NATO members and Japan (which has essentially decided it’s no longer demilitarized), and the numbers are even more lopsided:

Russia and China spend a combined $311 billion a year. NATO plus Japan spend a combined $1.138 trillion — a ratio of 3.7 to 1. If it’s just the U.S., the ratio is still about 2.5 to 1.

But does this mean we should lower our expenditure until we’re at parity? That’s certainly not what we did in World War 2. The Allies didn’t match Axis spending 1-for-1 — we outspent the Axis by a huge amount. Reliable figures are hard to ascertain, but by the estimates I can find, the U.S., USSR, and UK together outspent Germany and Japan by a ratio of 2 to 1.

The Pacific War was especially lopsided here. The U.S. outspent Japan by almost 5 to 1. And if you look at production of specific weapons, like warships, it’s just no comparison:

Looking at actual production numbers is important, because different countries get different amount of bang for their buck. In 2022, for example, soldier salaries and health care certainly cost less in Russia and China than they do in the U.S. When the economist Peter Robertson tried to take these cost differences into account to create a “military purchasing power parity” with which to compare military spending directly, he came up with the following numbers:

If you believe these numbers, then China and Russia together spend 86% of what the U.S. spends on its military, in effective terms. Add in the other NATO countries in the table, and the ratio is about 1.75 to 1 — still lopsided, but a little less lopsided than World War 2.

Matt kind of dismisses Robertson’s calculations, observing that the Russian military has performed far worse than expected in Ukraine. Unobserved differences in the quality of supposedly comparable goods and services are the bane of all PPP calculations, and this is no different. Perhaps in military spending you really do get what you pay for.

Then again, the Ukraine War has only tested one side of the equation here. Yes, U.S. soldiers are far better trained than Russian ones. No, we don’t know about how good the Chinese are yet (not to mention various U.S. allies). We also don’t know how good the U.S. will actually be against a peer competitor — just a few years ago, for example, there was an alarming series of naval accidents in the Pacific that might point to unidentified problems in our own military.

But an even more important argument here is that the balance of military spending is a lot more lopsided than the balance of potential military spending. Russia spends more of its (meager) GDP on defense than the U.S. does, but China spends far, far less:

That means that if a general great-power war breaks out, China has much more scope to increase spending than the U.S. does. Already the two countries’ GDPs are comparable. And China’s manufacturing output is almost twice that of the U.S., even without any PPP adjustment. China alone has about as much manufacturing output as the U.S. and all its allies combined.

This is a very different situation than World War 2. In that war, the Allies’ economies were 2 to 3 times as big as that of the Axis:

This was similar to the ratio of military spending.

In other words, if a major great-power war breaks out, or even just a U.S.-China war, it’s likely that Chinese military spending will kick into high gear and the U.S. will find itself struggling to keep up.

Looking at all of these numbers, I definitely do not feel secure that the U.S. has overmatched our potential enemies. In fact, given China’s economic size, it’s pretty clear we have no hope of overmatching them the way we did to Germany and Japan in WW2 — at least, not anytime soon. The argument that our military dominance is so secure that we can afford to slash spending therefore doesn’t make a lot of sense to me.

When should we start spending?

That still leaves the question of when we should do our spending. We are not yet in World War 3 (and hopefully we never will be). Does it make sense to spend wartime amounts on our military when there’s no war?

Well, first of all, we aren’t spending wartime amounts. As I noted in my last post, we spent over 13% of our GDP on the military during the Korean War, over 8% during the Vietnam War, and less than 4% today.

But OK, why should we spend double what China spends when there’s no war on? One reason is the enormous level of China’s potential spending, which I discussed in the last section. If a war does start, we’re going to see China ramp up military manufacturing to unimaginable levels — something like what the U.S. did in WW2. The U.S. won’t be able to match it, even if Japan helps. Instead, we’ll have to rely much more on what we have ready at the beginning of the war. That’s an argument for spending more now.

Note that even in WW2, we relied heavily on weapons that FDR started building years before the war even began. Construction of the USS Washington began in 1938. The B-17, the mainstay of our heavy bomber force, began construction in 1936.

The second reason to spend more now is deterrence. Remember, the best outcome is that no great-power war ever happens. And it’s clear that one reason Russia chose to invade Ukraine — and one reason China has been more threatening toward Taiwan recently — is that they thought the U.S. and its allies were militarily weak. Slashing defense spending could thus encourage adventurism by the totalitarian powers, raising the likelihood of a catastrophic war. International relations scholars generally seem to agree that even in the age of nuclear weapons, conventional deterrence is still important. (Update: Here is a very good article with research showing the continued effectiveness of deterrence.)

The problem of deterrence is that you never know whether you were successful or not — or whether you needed to spend as much as you spent. If your enemy never attacks, maybe they never were going to attack at all. Or maybe you could have deterred them with only half the amount of spending you actually did. It’s a little bit of a Cassandra situation.

This leads to some grim but instructive thought experiments. Suppose that slashing our military spending by $200 billion (a 25% cut) would increase the risk of World War 3 by 0.1%. And suppose WW3 would kill 1 billion people. In expectation, that’s a loss of 1 life for savings of $200,000 — an order of magnitude below the commonly used figures for the statistical value of a life, even completely ignoring the economic costs of WW3. Now, I made up the 0.1% number, but I don’t think it’s out of the realm of plausibility, and I think it gives some account of the magnitudes involved.

And that’s just in expectation. When you think about this in terms of risk, it makes sense to be even more cautious. If we fail to deter Russia and China from starting more wars, much of the human world is utterly ruined. But if we waste $2 trillion over ten years trying to deter a war that wouldn’t have happened anyway, well, that’s as much as we wasted on the Iraq War. The world did not end.

What should we buy?

Then there’s the question of what we should be spending our money on. Like most critics of defense spending, Matt cites the F-35. But his main example is aircraft carriers:

[T]he Ford-class aircraft carriers are an even clearer example [of waste]. They cost $13 billion a pop over and above massive R&D costs that can’t be spread out with international sales because nobody wants a gigantic $13 billion aircraft carrier. And they aren’t just expensive; it seems like in the event of a war with China, they wouldn’t actually be used because China’s short-range missiles are too good (this is called A2/AD for “anti-access area-denial” in military jargon). For a really strong version of this case, you can read former John McCain staffer Christian Brose’s book “The Kill Chain” in which he argues that almost all the big American military platforms are nearly useless.

And Matt uses the recent sinking of the Russian missile cruiser Moskva by Ukrainian shore-based missiles to argue that surface warships are now basically just sitting ducks.

I’m sure Christian Bose makes his case against aircraft carriers — and our other main weapons platforms — quite eloquently. And in fact, I tend to agree — my own favorite naval analyst is Naval War College professor James Holmes, and he thinks it’s quite possible that carriers are going the way of battleships and that we should prioritize building the capital ships of the future.

But Matt and I are just politics and econ bloggers, and we can’t just pick whatever analyst suits our fancy and conclude that they’re right. There are many analysts who dispute these claims. For example, Sidharth Kaushal, a research fellow for Seapower at the Royal United Services Institute, argues that aircraft carriers will simply see their combat role altered. That would be similar to what happened to battleships at Guadalcanal, where they were useful not for capital engagements but for shore bombardments and night fights. Some other analysts argue that carriers aren’t even obsolete in their primary role yet. After all, China is building them.

More fundamentally, this disagreement among knowledgeable experts shows that we don’t really know what weapons platforms we’ll need in the case of a major fight with China and Russia. The Ukraine war is giving us some info about land warfare, but sea warfare is still an open question. It’s possible we might need aircraft carriers and some new kind of ship — just as in WW2 we ended up needing both surface combatants and aircraft carriers. The fact that we don’t know what we need is a risk, and the way to mitigate risk is diversification. That means that instead of canceling aircraft carriers, manned fighter jets, and tanks, we should keep these around but also build other newer stuff if we want to have the best chance of winning a major war.

That would probably require increasing spending rather than cutting it, even if we did trim the size of the legacy platforms. That new stuff will cost money too — perhaps even more money than the old stuff did, since it’ll require a bunch of R&D and testing.

In the end, WW2 is an instructive example here as well. I am glad that when crunch time came, we had both a robust carrier fleet and the USS Washington. That took a lot of money.

Defense spending and inflation

There is an important economic argument I should address here, which regards inflation. Matt notes that when we embarked on our pre-WW2 defense buildup, we had a ton of slack in the economy — it was the Great Depression, and there were millions of American workers who needed jobs. As of 2022, the situation is very different — instead of slack in the economy, we have accelerating inflation. People generally think that inflation results from an economy using up all its available resources, so that too much money ends up chasing too few goods, which pushes up prices. So the argument is that if we spend more on defense right now — or even fail to cut defense spending — then we’ll put even more of a strain on our resources, and exacerbate inflation.

I’m not convinced. First of all, the biggest resource that production uses is always labor. And I don’t think a labor shortage is what’s pushing up inflation right now. If we had a labor shortage, we’d see wage gains outpace inflation. Instead we see the opposite — real wages have been falling steadily since early 2021.

So I don’t worry that military spending will suck up scare labor, since labor isn’t really scarce yet.

What about other resources? Military equipment certainly uses computer chips, and there’s been a chip shortage. But in fact, core inflation — which is what semiconductor shortages should influence — is decelerating a bit, even as headline inflation rises. This is consistent with a change in the drivers of inflation. Stimulus spending is over and supply chain snarls are starting to resolve themselves, but the war in Ukraine is pushing up the prices of food and energy. So I doubt that military spending is contributing especially much to inflation right now. Certainly, Biden’s $30 billion additional defense spending request — which barely keeps up with inflation itself! — is not going to make any appreciable difference here.

It is true that when there’s not a lot of slack in the economy, we need to evaluate military spending on its own merits, rather than just as a way to boost demand. But I would argue that FDR’s WW2 spending — and his pre-WW2 spending — were useful in their own right, as more than just a form of “weaponized Keynesianism”. It was a good thing that when the greatest crisis of the 20th century rolled around, we had the tools we needed to deal a decisive defeat to the forces of totalitarianism. If being similarly prepared forces us to give up a percentage point of GDP in consumption in the 2020s, I think that’s not too high a price to pay. It’s comparable to the price we’re asking Europeans to pay just to stop buying Russian gas.

So let’s wrap up here. Should we try to find and cut waste in military spending? Yes, of course. Should we try to improve the procurement process to get more bang for our buck? Yes, of course. Should we be trying to figure out what new sorts of weapons platforms we need in order to defeat China and Russia should a confrontation come, and to deter them in the hopes of avoiding such a confrontation? Yes, of course.

But should we slash defense spending overall? I just don’t see a case for that.

Deflationary forces were really strong for a decade. Current inflation is high, true. But it is not clear at all that the anti-inflation forces are going to disappear from the world in the long term. Maybe we need a new kind of Hitler, this time from Russia, to give purpose and meaning to our spending. Spending money against him can be a rare consensus, agreed by republicans and democrats alike. Agreeing to spend money against a murderous dictator, that's how the big depression ended for good in the thirties. That's the invasion from Mars Paul Krugman used to talk.

Great article. I agree with most of what you said. The only real omission in your article IMO is the cyber warfare component. It relatively cheap, the USA has vast skill sets to call on. And it can disrupt both the front line battle field and mainland infrastructure and manufacturing.