Covid doom predictions that never happened

Five prophecies of economic ruin that thankfully didn't come to pass

Unfortunately, many of the bad predictions about COVID-19 came true. The people who saw cases ramping up exponentially, and warned that this was going to be a mass death event, were right, while the people who minimized the threat and waved it away were wrong. And a lot of people are dead because we didn’t listen to the former.

But economic predictions are a different story. When unemployment spiked to Great Depression levels in the early days of lockdown, it seemed to me — and to many, many others — like this downturn was destined to turn into a decade of mass economic hardship. Fortunately, that was completely off the mark! I got it very wrong and Paul Krugman got it right — with no financial crisis and no big overhang of debt, the economy simply wasn’t destined for a repeat of 2008-12. Though the recovery has proven bumpy thus far, but most economists still forecast a relatively swift return to the pre-pandemic growth trend.

In fact, this was one of many predictions of economic doom that failed to materialize. Here’s a quick list of a few others.

1) Suicides fell

Suicides had been rising in the U.S. for years prior to the pandemic, and many people predicted that the stress and isolation of lockdown would send the rate soaring even higher. An article in JAMA Psychiatry in April 2020 predicted:

Remarkable social distancing interventions have been implemented to fundamentally reduce human contact. While these steps are expected to reduce the rate of new infections, the potential for adverse outcomes on suicide risk is high.

The Washington Post said we were headed for a mental health crisis, and predicted a wave of suicides. Other researchers reported a rise in suicidal ideation.

Except guess what happened? Suicides fell. A March 2021 JAMA article found that suicide was about 6% lower in 2021 compared to 2020:

What happened? Maybe it was the government’s generous economic bailouts that gave Americans heart, or maybe suicide is just a complex process that responds to external events in ways we don’t really understand yet. Either way, it’s a very good thing that this prediction was wrong.

2) Savings and net worth rose even as consumption bounced back

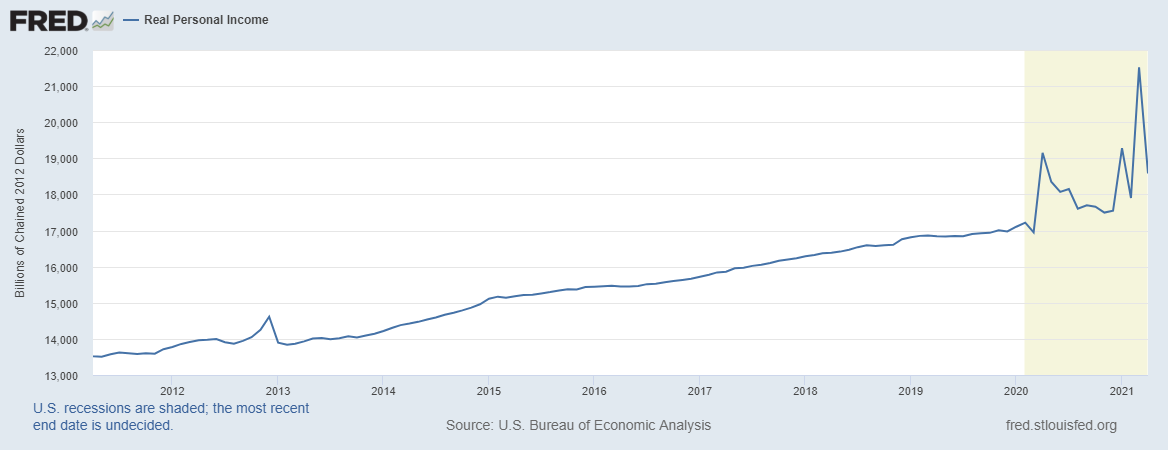

It was widely predicted that average Americans would be ruined financially by the pandemic. Which made sense — unemployment and the loss of various other sources of income would force Americans to spend down their meager savings in order to sustain themselves. But in fact, that didn’t happen. Savings rates actually spiked in the early part of the pandemic, and stayed high throughout:

Meanwhile, stock and housing markets boomed, causing household net worth to rise:

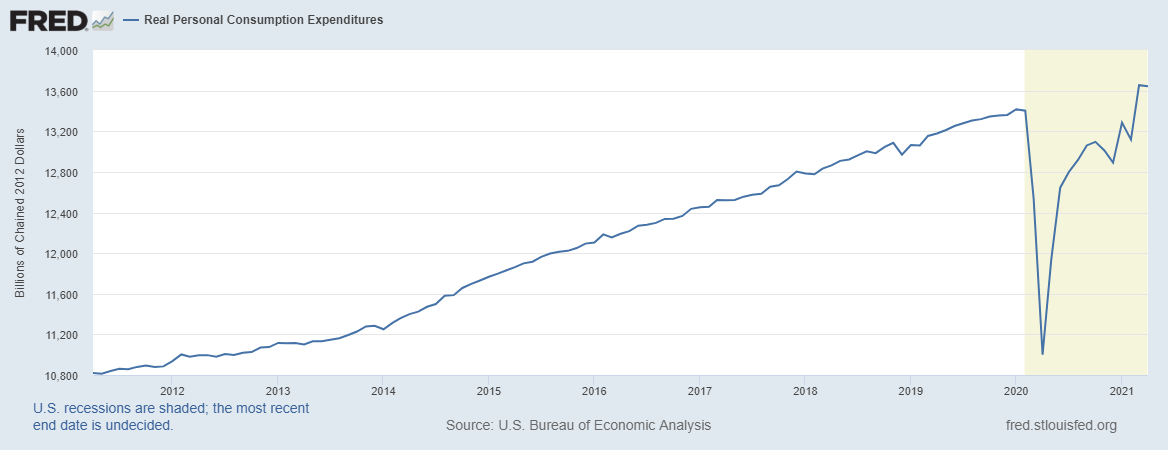

Some of the increase in savings did come at the expense of consumption, but in fact, consumption bounced back faster than economists expected:

How did people manage to save more while quickly restoring their pre-pandemic levels of consumption? The quick recovery has a lot to do with it, but there’s also the fact that personal income has gone way up as a result — once again — of those generous relief bills.

Now, these are all aggregate numbers, and they hide a lot of heterogeneity — there will certainly be people who fall through the cracks in the relief spending programs or are financially ruined by the economic shifts and dislocations associated with the pandemic. And people still expect long-term financial difficulties. But overall, Americans’ finances are looking healthier now than before Covid, and that’s quite a surprise.

3) People are paying their rents and mortgages

It was very natural to assume that with their incomes getting clobbered, people wouldn’t be able to make their mortgage payments. After all, that’s what had happened in the Great Recession. It was also assumed that millions would fail to make rent and would be evicted from their homes. Here’s NBC News from March 2020:

Federal, state and local governments have scrambled to enact policies to keep renters whose sources of income have disappeared from getting evicted…But experts say the initial steps are nowhere near enough to protect low- and middle-income renters…

"In terms of the across-the-board, really big, social policy, human need issue, this is it," Andrew Scherer, a law professor at New York Law School, told NBC News of what he sees as an impending crisis. "This is what's looming."

Except people did manage to pay their rent. The percentage of people who made rent payments on time fell only slightly:

Again, generous relief bills were probably responsible. Between that flood of government cash and anti-eviction moratoriums — and the fact that kicking people onto the street during a pandemic is just a generally crappy business decision — evictions appear to be lower than before the pandemic.

The same pattern holds for most cities in the country.

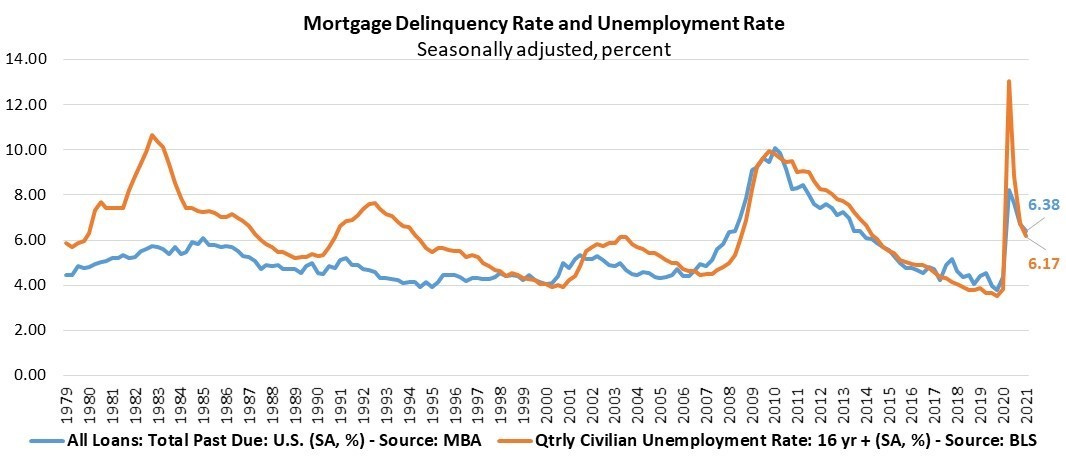

Meanwhile, the mortgage delinquency rate did spike, but not to Great Recession levels, and is now coming back down pretty fast:

Now, this could reverse. People are still warning of waves of evictions and mortgage delinquencies to come. But so far it just hasn’t happened.

4) State budgets are healthy

The Great Recession clobbered state budgets, and they never really recovered. It was natural to expect that the COVID-19 recession would have the same effect. Most people predicted giant budget gaps and called urgently for a federal bailout of the states. Here’s Brookings, from April 2020:

[I]n the coming months, states will experience large declines in tax revenues and increased enrollment in safety-net programs as disruptions caused by COVID-19 drive incomes and consumption lower. Without assistance from the federal government, states will likely be forced to make deep program cuts, enact substantial tax increases, or both.

But fortunately, the crisis never happened. The relief bills raised income, and that income got taxed, filling states’ coffers. Capital gains taxes resulting from the big stock market boom helped too. This May it was reported that California has a $75.5 billion budget surplus. New York has a more modest surplus, as does Texas.

In fact, by the time Biden gave states a big dollop of federal cash, most probably no longer needed it.

5) Business formation increased

Though it wasn’t unanimous, many people believed early on that the pandemic would crush entrepreneurship. In fact, during the early days of the pandemic, new business formation did fall substantially.

But then a funny thing happened — the trend reversed itself with a vengeance! By the end of 2020, business formation was way up compared to 2019:

After cratering by 30% in the weeks following the March lockdowns, paperwork filed by prospective businesses started growing in June and finished the year ahead of 2019’s tally by almost a quarter…It was the highest annual total on record[.]

[T]here is reason to think the boom is legitimate, said Barry McCarthy, chief executive officer of the small business services giant Deluxe Corp. A Deluxe unit that helps startup businesses to incorporate was up 10% last year compared to 2019, and its unit that prints checks for small businesses saw a “dramatic” increase in orders, McCarthy said.

Many of these businesses were online stores.

Necessity, it seems, really is the mother of invention. Relief spending undoubtedly helped, but I think this positive surprise should be mostly chalked up to Americans’ inventiveness and can-do spirit.

…But universities really are in trouble

Unfortunately, not all of the doom takes were wrong. I repeatedly warned that the pandemic would crush many U.S. colleges and universities, by reducing demand and sending tuition cratering (after state funding was already heavily slashed after the Great Recession).

Unfortunately, there are a number of indicators that this particular doom prediction was pretty right. More than 1 out of 8 higher ed jobs were lost in 2020:

And relief doesn’t look to be on the way. New data shows that undergraduate enrollment is down 5% in 2021 compared to 2020. That’s going to hit a lot of colleges hard. Mills College and a number of others have already closed down.

Why did this pessimistic prediction come true when others didn’t? The shakeout in the higher ed sector is probably due to trends peculiar to that sector, which were already in evidence before the pandemic struck. Federal bailouts, unless they turn into permanent federal funding, are unlikely to reverse those trends.

Why did we get it so wrong? And what have we learned?

Overall, most of the grim forecasts of economic doom ended up not coming true — or at least, not so far. Why? Was everyone just being emotional and panicky in the early days of the plague? I don’t think so. I think those who issued doom-and-gloom predictions got two things wrong.

First, they used the Great Recession as a model. Paul Krugman had this exactly right from day 1 — this recession was not an aggregate demand deficiency due to a financial crisis and debt overhang. It was something else entirely, and there was no real deep fundamental reason we couldn’t bounce back a lot faster from this one. The Great Recession traumatized us and made us pessimistic; perhaps the swift bounceback from Covid will undo some of that trauma.

Second, forecasters couldn’t have predicted the breathtaking size and boldness of the three U.S. relief bills, which together were far more generous even than what our rich-world peers offered:

That bold decisive action on the part of the U.S. government, which set aside our usual stinginess and skepticism of welfare spending, was instrumental in staving off economic devastation for millions of vulnerable people. American ingenuity and determination was very important, of course, but we couldn’t have come through the pandemic nearly this strong without a helping hand from our government.

"forecasters couldn’t have predicted the breathtaking size and boldness of the three U.S. relief bills"

Just to push back on this slightly -- predicting the response of institutions is exactly part of the prediction game. I see this kind of excuse a lot in stock market predictions where (bearish) prognosticators often say something like "my prediction would have been totally right except the Fed did stuff". Predicting the Federal Reserve response is part of your job! It is part of the equilibrium you're solving for!

Biden was talking about massive stimulus at least as far back as March 2020. It isn't like predictions had to predict huge stimulus based on zero evidence. All you had to do was take a presidential candidate at his word. From an April interview with Politico:

"The former vice president said the next round of coronavirus stimulus needs to be “a hell of a lot bigger” than last month’s $2 trillion CARES Act"

Great post. Just two minor things: 1) great news that suicides fell, but I don’t think it necessarily means the pandemic wasn’t associated with spikes in poor mental health. There’s lots of reasons why those are two related but different questions. 2) Mills College, at least, was absolutely already going to close before the pandemic. I knew people who worked there and the writing was clearly on the wall before (one actually left a couple years ago specifically because it was clear the institution wouldn’t exist in a few more years), so I don’t think it’s quite right to blame the pandemic for that specific example, though of course the broader issue of the devastation the pandemic is wreaking on higher ed is of course true.