Climate is just one piece of industrial policy

It can't take precedence over everything else, all the time.

Interfering with markets in a rich country requires a justification. Markets, if they’re properly regulated, are a very efficient way to maximize a nation’s overall income. Problems of inequality and poverty can be solved through redistribution and measures to improve worker bargaining power; the occasional recession can be dealt with through monetary and fiscal stimulus. This basic formula — call it the neoliberal/social-democratic mixed economy — has produced the most highly developed and happiest societies on Earth. If you’re going to mess with that formula by having the government come in and start mucking around with a country’s industrial structure, you need a good reason.

The U.S. and our democratic allies have a very good reason: national security. The China-Russia Axis requires democracies to rebuild and enhance their own manufacturing industries, and this requires interfering in the free market in some way. Industrial policy is a big part of that.

But those national security concerns only really became widespread in the past five years. The shift in U.S. economic thinking was actually underway well before that. I remember in 2017, going to a Bloomberg conference where almost everyone — mostly a bunch of progressive intellectuals from tech, think tanks, and the media — was talking about the need to bring industrial policy back. But China was never mentioned — the big justification that everyone cited was climate change.

I remember hearing everyone talk about how the fight against climate change required an industrial mobilization on the order of World War 2 — to build green energy, switch to EVs, revamp our industrial processes, and refit or rebuild buildings. And the market wasn’t moving fast enough. Like Jimmy Carter in the 1970s, my friends in 2010 believed that an energy transition could be the moral equivalent of war.

This idea made it all the way into the Biden administration. Of Biden’s three signature industrial policy bills, two of them — the Inflation Reduction Act and the infrastructure bill — are largely aimed at boosting green energy industries in order to combat climate change. The progressive intellectuals of the 2010s triumphed.

But now, with Biden’s new tariffs on Chinese EVs, batteries, and solar panels, the script has flipped a bit. A number of progressive thinkers who cheered the rise of green industrial policy are dismayed that the U.S. is going to make green tech products more expensive. For example, David Fickling writes:

The administration has committed hundreds of billions of dollars toward accelerating the transition to electric vehicles. Yet in order to head off a surge of imports, it recently announced 100% tariffs on EVs made in China — thereby delaying the transition it rightly insists is essential.

Biden and his officials appear to be confused. They can make fighting climate change their top priority, or let their overriding goal be protecting US producers from foreign competition. They can’t do both…

In the end, it isn’t that complicated: If climate change is an existential risk, surging output of good, cheap Chinese EVs is a good thing.

Dylan Matthews made a similar argument back in March:

[Chinese EVs] are absolutely screaming deals — exactly the kind of products that could turbocharge our transition away from gas and toward electric vehicles…The problem for Americans? The Biden administration is hell-bent on preventing you from buying BYD’s product, and if Donald Trump returns to office, he is likely to fight it as well.

That’s because the BYD cars are made in China, and both Biden and Trump are committed to an ultranationalist trade policy meant to keep BYD’s products out…The Chinese EV case is a good demonstration that however motivated the Biden administration might be by climate concerns, it is much more motivated by a desire to help American automakers, to win Michigan’s electoral votes this November, and to escalate a brewing cold war against China…It has proven shockingly willing to sabotage its own climate policy if it gets to stick it to the Chinese in the process.

Others have echoed this argument.

If climate change really were the main reason for the big changes in U.S. economic policy, then Fickling and Matthews would be right, and it would behoove the U.S. to follow their advice. But despite what many of my friends and colleagues thought back in 2017, climate change is not actually the main reason for industrial policy, nor will it be going forward. And so they are shouting into the wind.

The reason for this is not just that national security concerns take precedence in the minds of the American elite — though that is certainly true. For a number of other reasons, climate change is ill-suited to being the main driver of changes in U.S. economic policy. On the public opinion side, it doesn’t motivate the voting public, and it has a lower likelihood of bipartisanship. Meanwhile, cheap Chinese imports are probably not going to be a pivotal factor in the green energy transition.

So while climate policy is important, it just can’t stand on its own. Instead, it must be just one part of a suite of policies aimed at reinvigorating American industrial might.

Climate change is real and important, but it doesn’t motivate the electorate

Anyone who denies the reality and the importance of manmade climate change at this point has their fingers lodged firmly in their ears. Temperatures are rising steadily, with year after year being the hottest on record:

For rich countries like the U.S., Canada, and Australia, climate change’s harms are manifesting in terms of increased wildfire risk and increased risk of coastal flooding. For many poor, equatorial countries like India, it’s manifesting as unbearable heat waves that are causing water supplies to run short and making urban conditions unlivable. And worse is on the way — both model projections and consensus forecasts are for the climate to heat up by about 2.7°C this century (which is a lot), while even a mighty global effort will still involve things getting somewhat worse are now. So hold on to your hats — it’s going to be a bumpy ride.

So everyone should care quite a lot about climate change. But me saying that won’t make it so. And the unfortunate truth is that despite decades of activism and elite rhetoric, the voting public just doesn’t put a high priority on climate issues. Matt Yglesias explained this back in January:

Some excerpts:

[I]f you probe public opinion even slightly, it’s clear that public support for climate action is a mile wide and an inch deep. For example, IPSOS found that just 25 percent of Americans said they’d be willing to pay higher taxes to address climate change. A 2019 Reuters poll asked specifically whether respondents would pay $100 to fight climate change and only a third said yes. Would you be willing to pay $10/month more in electricity bills to fight climate change? Most people say no.

Perhaps this could change if voters were persuaded of climate change’s importance. But activists have been maximally shrill for many years, and while this seems to have helped raise awareness among the elite (which is good!), it has singularly failed to make climate change a popular cause among the general public. Now climate activists — at least, the ones who haven’t pivoted to Palestine — are focused on bashing Democrats, engaging in unpopular stunts, and making ever-more-dire claims like “12 percent of the population of Phoenix, Arizona will die of extreme heat in the 2030s.”

It just isn’t working. Voters should care, but they’re steadfastly refusing to care. Democrats have emphasized climate change in their rhetoric for decades, and Americans still aren’t ready to declare war on fossil fuels.

Meanwhile, while a substantial portion of the GOP is on board with the need to stand up to China, the issue of climate tends to activate their partisan instincts. While some Republicans did support the infrastructure bill and a few other minor bills to boost electric vehicles, zero voted for the much larger Inflation Reduction Act. And polls show that EVs have become the focus of a culture war — liberals strongly approve of electric cars, while conservatives disapprove of them by a 2-to-1 margin.

A shift in a nation’s economic policy requires both parties to be on board — not generally through bipartisan cooperation, but by competing to put their own stamp on the basic paradigm. Eisenhower and Nixon both left their imprints on the New Deal, while Carter and Clinton implemented key parts of the “neoliberal” revolution. Most Democrats and a majority of Republicans are definitely on board with national security, and both understand the importance of industrial policy in that realm. But the GOP simply rejects climate policy as a guiding orientation for the U.S. economy.

So climate change will remain divisive. That won’t make climate policy impossible, but it will prevent it from becoming the central, overriding imperative of economic policymaking.

Fortunately, it doesn’t need to be.

The green energy transition will happen even if climate isn’t always Priority #1

The gains from reducing U.S. emissions are modest but far from trivial. Some analyses find that Biden’s economic policies would result in a decrease of approximately 1.7 billion tons of CO2 equivalent emissions by 2030 compared to Trump’s policies. That’s about 4.6% of global emissions in 2022 — not a huge amount, but not nothing either. China will still be more important than the U.S. for the fight against climate change (and there are hopeful signs that it’s doing better these days), but the U.S. can certainly do a lot to help.

Here’s where U.S. greenhouse gas emissions come from:

In order to decarbonize, we need to do the following four things:

Switch to green energy — mostly solar backed up by battery storage, but with some nuclear and wind as well

Switch to electric cars, buses, and other vehicles

Electrify home heating (and cooking)

Electrify a bunch of industrial processes like steel and cement, or use other green equivalents

Basically, you can boil this down to 1) electrify everything, and 2) make sure that the electrical grid itself runs off of green energy.

Fortunately, two miraculous technologies have emerged to make both of these tasks much, much, much easier than they would have been back in 2010 or 1990. Solar and batteries are on steep learning curves — as we produce more and more of them, their prices have plummeted exponentially. As a result, solar is on a faster expansion path than any energy technology in history:

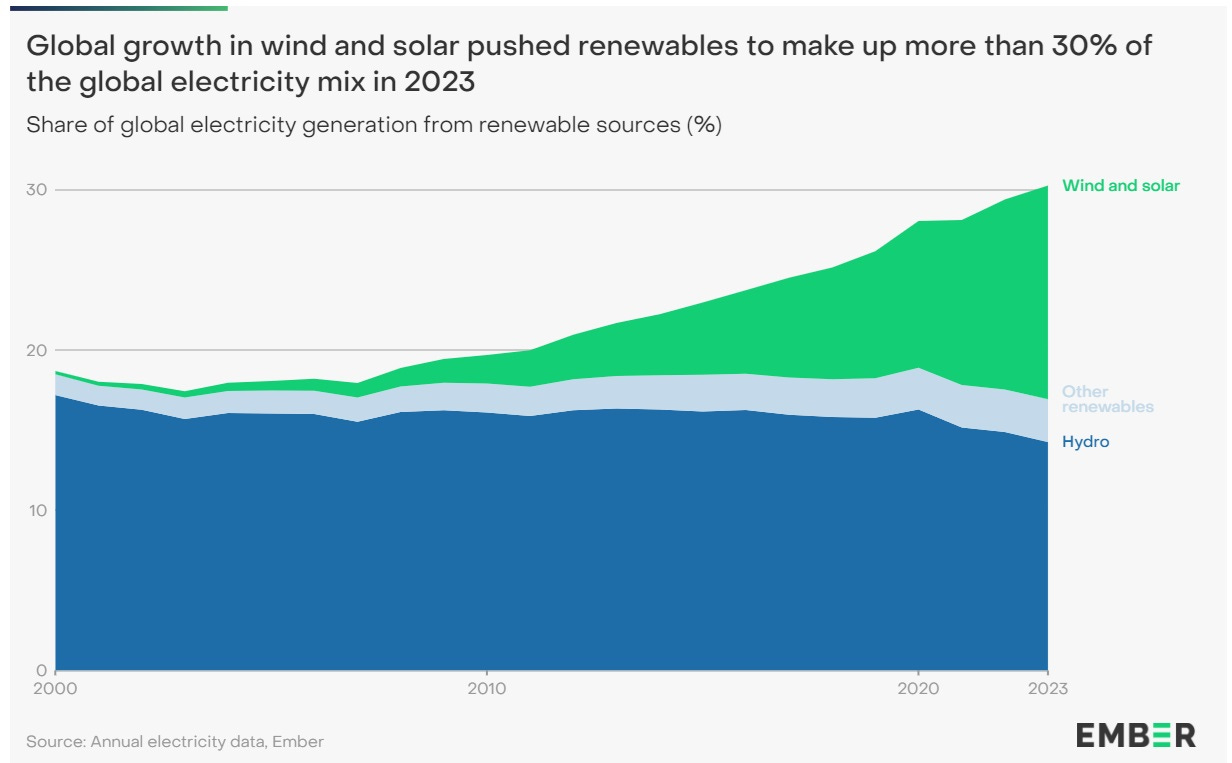

A recent report by Ember found that solar and wind now generate around 12% of global electricity — that’s actual generation, not “capacity”. When you add that to existing hydropower, renewables now generate around 30% of the world’s electricity, and rising fast:

The U.S. is not lagging here. In March, according to the EIA, solar and wind generated 21.2% of U.S. electricity, renewables generated 29.9%, and renewables and nuclear combined generated 49.4%.

Although Biden’s climate policies are great, they haven’t had much chance to take effect yet, and many countries don’t have similar policies in place. The rapid shift toward renewables is being driven by technological improvements that make renewable energy — especially solar and batteries — really cheap.

We can see this just by observing the actions of countries and states that care much much more about economic growth than about climate change.

India, despite suffering intense heat waves, makes growth its overriding priority and reserves the right to continue using fossil fuels on the grounds that Western countries industrialized using fossil fuels in their day. And yet in the first quarter of this year, solar installation in India was up by more than a factor of six since last year.

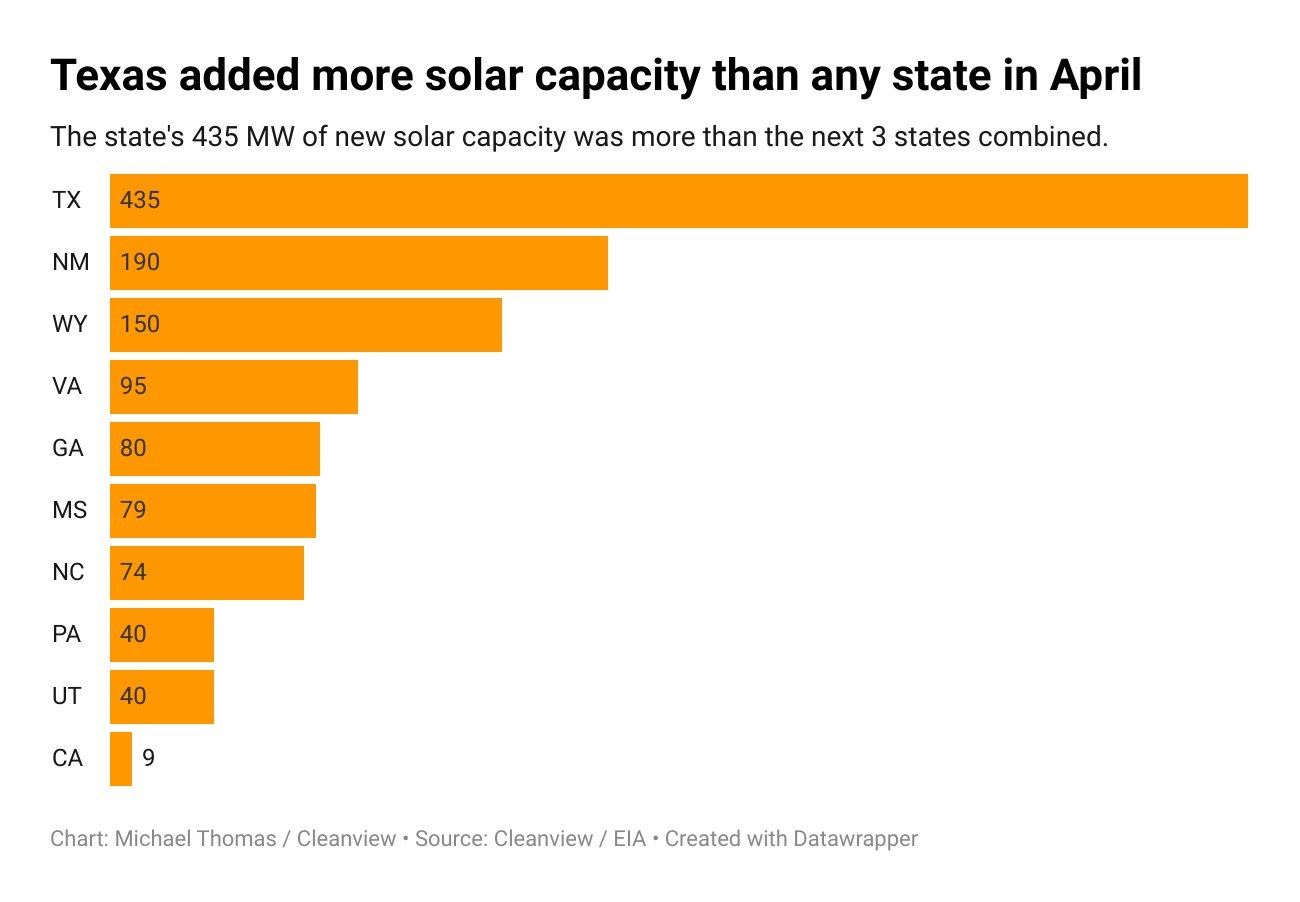

And Texas, a deeply conservative state that’s also the center of America’s fossil fuel industry, is outpacing California and everybody else in terms of building solar:

In fact, solar and wind are proving to be Texas’ most reliable sources of electricity.

Meanwhile, Texas and California are adding massive amounts of battery storage that is smoothing out the daily intermittency of solar power (i.e., you can store energy for when it’s nighttime or raining). That still leaves seasonal intermittency to deal with (the sun is weaker in winter), but that’s a much easier problem to solve; at the very least, you can overbuild more solar.

In other words, solar with battery storage is proving that it’s now simply the cheapest form of energy to build — provided you can get the land, get through the permitting process, and hook it up to the grid. And this is all happening with tariffs of 25% on Chinese solar panels, too.

Now, you could worry that Biden raising tariffs on Chinese solar panels from 25% to 50% will put an end to the solar boom. But it won’t. First of all, solar panels have gotten so cheap that the cost of the panels themselves is only a small percent of the cost of a solar system — most of it is the land cost, installation labor, etc. So the new tariffs will raise the price of solar by a couple of percentage points at most — not nearly enough to affect the cost calculation of solar vs. coal or gas. And second, U.S. solar manufacturing capacity by itself is enough to meet half the country’s needs, without even taking into account imports from places like Mexico or Canada.

Tariffs on batteries going from 7.5% to 25% might be a more significant factor, given China’s dominance of the battery market, and the fact that battery storage is pretty essential for solar power. But battery costs are forecast to drop 40% over the next two years, more than canceling out the tariff. Meanwhile, U.S. battery capacity is ramping up pretty quickly, and is on track to meet all demand for electric vehicles, so adding capacity to meet the needs of electrical grid storage should be doable, even if we don’t consider imports from countries like Mexico and Canada. EV batteries can act as grid storage too. And the U.S. has plenty of lithium to make batteries.

In other words, the technological revolution now well underway in solar and batteries will usher in the age of green electricity regardless of tariffs. What’s most needed now in order to accelerate the transition even further are regulatory changes — permitting reform, easing of land use restrictions, and reform of the outdated and inefficient interconnection queue system for hooking power up to the grid.

The other big shift the U.S. is to switch to electric vehicles. Transportation represents the biggest single category of U.S. emissions, so this is very important. And it’s here that tariffs might have a bigger effect. Biden’s 100% tariffs on Chinese-made EVs are high enough that they effectively constitute a total ban. And China is the country that makes the world’s cheapest EVs — and probably the highest-quality EVs too, at this point. So it’s reasonable for David Fickling and Dylan Matthews to be concerned.

But so far, even without any significant amount of EV imports from China, the transition to EVs in the U.S. has been going fine:

For every sign of an EV slowdown, another suggests an adolescent industry on the verge of its next growth spurt. In fact, for most automakers, even the first quarter was a blockbuster. Six of the 10 biggest EV makers in the US saw sales grow at a scorching pace compared to a year ago — up anywhere from 56% at Hyundai-Kia to 86% at Ford. A sampling of April sales similarly came in hot.

The slowdown this year in U.S. EV sales has nothing to do with China; it’s all about Tesla suddenly failing to offer new products (including a promised cheaper EV). Tesla still makes most of the EVs that Americans buy, but the company has been faltering lately. That means there will be a lull in sales as other automakers — American companies, but also German and Korean companies — ramp up from a low base. But ramp up they will, and the EV boom will continues, especially as batter capacity expands and costs keep coming down.

And eventually, a tipping point will come where EVs just rapidly take over the entire auto fleet in the U.S. Here’s how I explained it in a post last year:

There’s a network effect between gas stations and cars on the road — the more gas stations there are, the more convenient it is to drive, and the more people drive, the more profitable it is to run a gas station. This is why we have a lot of cars and a lot of gas stations; they reinforce each other.

By taking internal combustion traffic off the road, EVs are going to make gas stations less profitable to run. Gas stations have fixed costs that they need to make up for by catering to large volumes of customers; when they can cater to fewer customers, their fixed costs are harder to pay, and some go out of business (or switch entirely to EV charging stations). When the number of gasoline-powered cars on the road goes down by double-digit percentages, it’s going to lead to a lot of closures or conversions.

When some gas stations vanish, it makes it harder to drive an internal combustion car as your primary mode of transport. This is because gas stations are fewer and farther between. This creates range anxiety if you’re on a long trip, but it also just forces you to drive farther and every time you fill up. That gives people an incentive to switch to an electric.

Now, it’s true that a flood of cheap Chinese imports would probably make this tipping point happen a bit sooner —Chinese EVs would be a bit cheaper than Teslas or Kias, and this would spur modestly faster adoption. But the emissions benefits of that modest acceleration would be more limited than people think. The reason is that the manufacturing processes for EVs are not yet decarbonized, and so EVs produced today have only modest life-cycle emissions benefits compared to ICE cars. That will change in a few years, of course, as the electrical grid decarbonizes and as EVs are used to make more EVs. But enticing a few Americans to switch to EVs a few years earlier than they otherwise would will have only limited benefits for the climate.

In other words, the green energy transition in the U.S. is already happening, driven first and foremost by technological advancements, with Biden’s industrial policy giving an extra push. The biggest bottlenecks in that push are regulatory barriers — NEPA and other permitting reform laws, the broken grid interconnection system, and so on — rather than a lack of sufficiently cheap Chinese imports.

Climate policy as part of a bigger industrial strategy

Meanwhile, some progressives are now making persuasive arguments that Biden’s approach, tariffs and all, is the right long-term approach. Robinson Meyer writes that by keeping U.S. manufacturers in the political coalition for climate action, protectionism will actually help sustain the political will for continued decarbonization, even in the face of Republican hostility:

This is the guiding logic of Biden’s climate policy: that American politics must have a powerful, durable, and flexible pro-decarbonization coalition if the U.S. is to succeed in reaching net zero. Achieving this coalition is the underlying aim of the IRA, the EPA rules, and — yes — the recent tariffs. This is what I wish critics understood about the president’s climate strategy: Biden’s strategy won’t have succeeded if the U.S. makes some headway on emissions but imports all of its decarbonization tech from China. The U.S. actually has to develop its own supply chain and manufacturing base to build the kind of deep economic coalition that can sustain long-term decarbonization. This is why trade restrictions have become so central to the administration’s world view.

The argument here is that if the U.S. gets slightly cheaper Chinese imports for a couple years, but this puts Detroit out of business and destroys the nascent U.S. battery manufacturing industry that Biden has worked so hard to build, it will cause a backlash against climate policy. But if climate policy remains wedded to American factory jobs, revitalization of declining American regions, and the profits of American companies, then even GOP culture wars won’t be able to kill it.

I don’t know whether Meyer is right, but this seems very plausible. As noted above, the political coalition for climate policy by itself is very weak, and apathy about the issue is widespread. But if climate policy is wedded to industrialism — which, yes, includes protectionism — the number and diversity of stakeholders in climate policy goes up dramatically.

Zachary Carter, meanwhile, argues that maintaining U.S. domestic industrial capacity is superior to relying entirely on the Chinese:

Where the fight against climate change is concerned, more is more, and friends of both the planet and geopolitical stability should want the world’s largest economy to be involved in the green technology of the future. To that end, Biden’s tariffs are a necessary step…Tariffs can’t do the work of economic development alone. They’ll have to be harmonized with green tech subsidies from Biden’s Inflation Reduction Act, coordinated with international allies, and adjusted in response to geopolitical change.

I think this is a good argument, but it’s a little vague as written, so let me try to flesh it out. If China massively subsidizes batteries, EVs, and solar panels, and if the U.S. opens its markets to these products completely, it will incur long-term risks. For example, a war with China, or other geopolitical tensions, could abruptly cut off America’s source of green tech products. Imagine if 70% of Americans drive Chinese-made EVs, and suddenly China cuts off trade so that Americans can’t buy new cars or get replacement parts — or even uses built-in backdoors to turn everyone’s car into a brick. That would leave many Americans just as helpless and stranded as when the Saudis reduced oil supplies in 1973 or Iran cut off oil in 1979.

That risk, in turn, will make Americans wary about climate policy. If fighting climate change means making their livelihoods dependent on the whim of the Chinese government, they will be unlikely to embrace it. But if climate policy means building up U.S. domestic industrial capacity, it will be more robust to shocks, and therefore less risky for Americans.

Carter’s idea, in a nutshell, is that it’s good for a country to have some degree of control over the technologies that are essential to its policy goals. That is a smart and reasonable argument.

In other words, the 2010s dream that climate change would be the moral equivalent of war — an overriding, unifying national challenge that would spur deep changes in America’s economic system — is not going to come true. But something even better is probably going to come true. Climate policy is going to be one piece of an integrated suite of policies for reindustrializing America. National security will be the top priority, but thanks to progress in green energy technology, that imperative will also entail switching America to solar and batteries. And because climate policy will be wedded to a broad coalition of stakeholders, it’ll be at least somewhat insured against cancellation by Republican antipathy and voter apathy.

Climate policy isn’t going to drive the car, but it will be along for the ride.

Great piece, and I strongly agree with it. One of the craziest things to me about the culture war is how different the reality is from the rhetoric — case in point, Texas being a leader in green tech even as politicians in Texas decry green tech as liberal nonsense. But Texas does let stuff get built, and this stuff makes money, so it happens anyway.

The secret has always been to make the new, green future actually better and/or cheaper than the status quo. Then the culture war evaporates and people will transition to new tech en masse.

Great piece, Noah. I learned some new things (US Lithium sources, for example.)

But one thing made me grind my teeth: "this requires interfering in the free market in some way". As an economist, you know full well free market models are not the real economy which very little resembles them. Nor are we starting to interfere with the market: we always have created, shaped, regulated, and changed the market.

This upsets me because it is accepting many decades of propaganda about markets which has been financed by the same big-money interests that brought us global warming and denialist propaganda about that and many other important subjects. Please don't use "free market" unless you are talking about abstract economic models.