So, I noticed that Neil Irwin tweeted the following:

He’s right. And it’s not just the Covid lockdowns, either. It’s Russian oil and gas, and Russian and Ukrainian wheat. So I guess I better write about inflation.

So, the background here is that we thought we had inflation basically contained. The Fed had announced a series of rate hikes, which seemed to reassure people that it hadn’t gone soft on inflation. Meanwhile, Covid relief spending — which was probably the biggest single driver of inflation — has dried up. As a result, inflation expectations moderated.

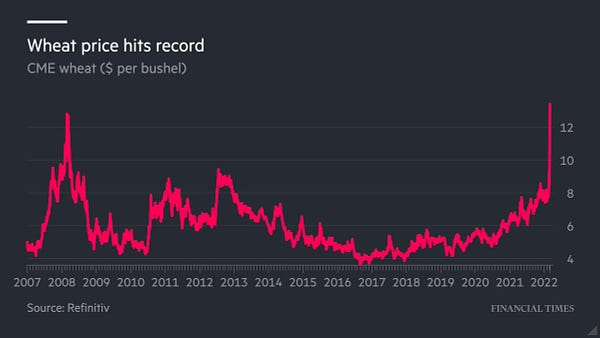

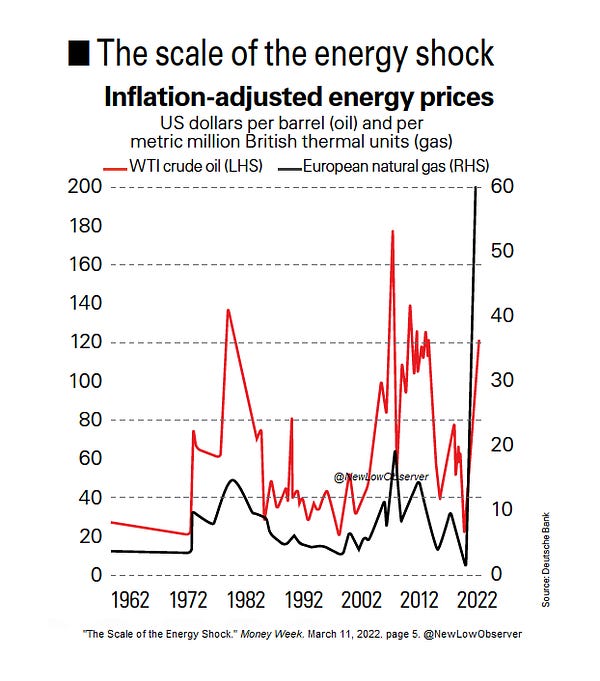

But then two things happened. The first was Vladimir Putin’s unprovoked invasion of Ukraine, and the resulting sanctions on Russian finance and fossil fuel exports. This is raising the prices of oil, gas, and wheat.

Whether or not these commodity price shocks push up core inflation (a more stable measure of inflation that excludes food and energy), they’re probably going to result in lower real wages for a lot of Americans, since wages probably can’t rise fast enough to keep pace with the prices of the things people need to buy. That’s going to make a bunch of people angry, and they’re likely to take it out on the Democrats in November.

But as if that weren’t bad enough, now we have the return of Covid in China. China doesn’t have a ton of Covid cases compared to, say, the U.S., but it’s very intolerant of any cases at all. So the government just put Shenzhen — a flagship Tier 1 city of 17 million people — into lockdown:

And Shanghai, another Tier 1 city, has heightened restrictions as well, suggesting that it may also be put into lockdown soon. This suggests that although Omicron technically can be contained — Taiwan somehow managed to do it — China may simply be too big of a country to suppress the hyper-contagious variant. That means that even if China never experiences anything close to a wave of the size America experienced, it could see continuous rolling lockdowns of whole regions for many months.

As a side note, this is partly China’s fault. If it had more effective vaccines, it might not feel the need to lock down in response to Omicron — it could instead manage outbreaks as they arose, while being confident that death rates would remain very low (in the UK, thanks to vaccination and Omicron’s milder nature, Covid death rates are now lower than death rates for seasonal flu). But instead, China relied almost exclusively on its homegrown vaccine, Sinovac, which has lower effectiveness than the vaccines developed by the U.S. and the UK.

Part of this was because of supply chain issues for manufacturing mRNA vaccines — China was able to make many more masks and Covid tests than the U.S., but it was the U.S. who was able to smoothly manufacture hundreds of millions of mRNA doses. For years now we’ve been hit over the head with the narrative that China is hyper-competent and can do anything it puts its mind to, while the U.S. is floundering and incompetent; hopefully, the story of mRNA vaccines should poke a hole in that narrative. But another reason for China’s refusal to use American or British technology was simply image-based — China felt that relying on foreign vaccines, especially after spreading bad rumors about these vaccines, was a threat to its government’s claims of superiority. As a result, until it can reinvent and mass-manufacture mRNA vaccines of its own, it’s stuck with lockdowns.

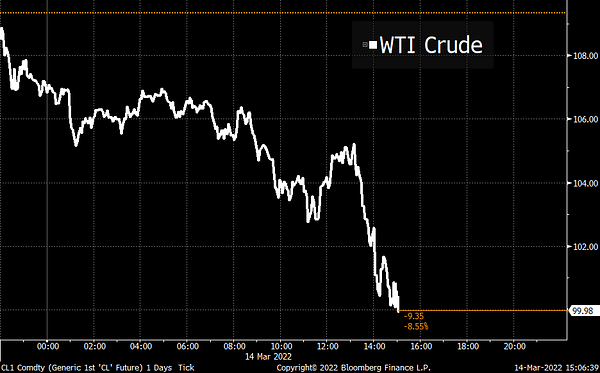

So anyway, back to inflation. China’s Covid lockdowns will probably decrease their demand for oil, which could mitigate the oil price shock from the Russia sanctions. That’s good. But it will also cause additional supply chain problems. Broken supply chains can make the economy less robust to inflationary pressures (such as an oil shock), and if severe enough, they can even cause inflation themselves by destroying economic activity outright.

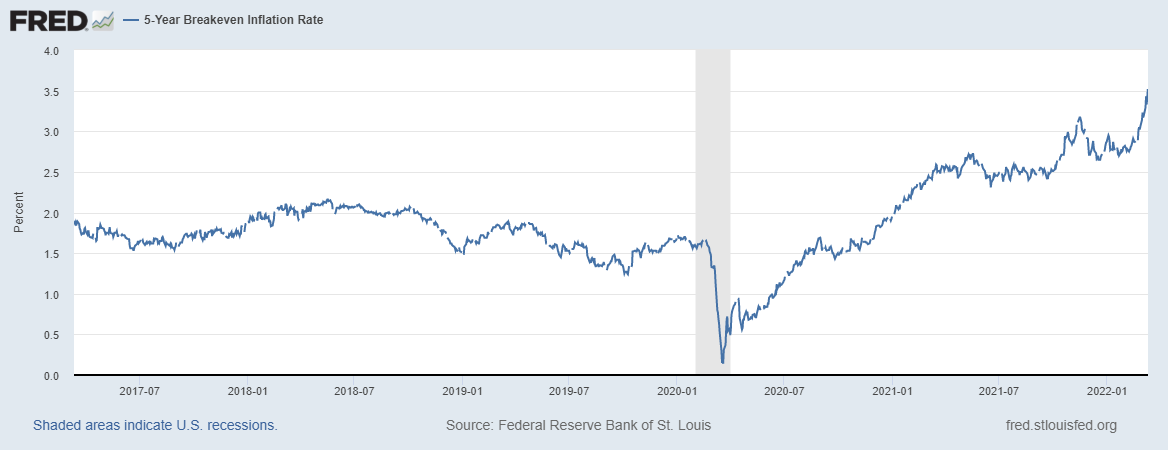

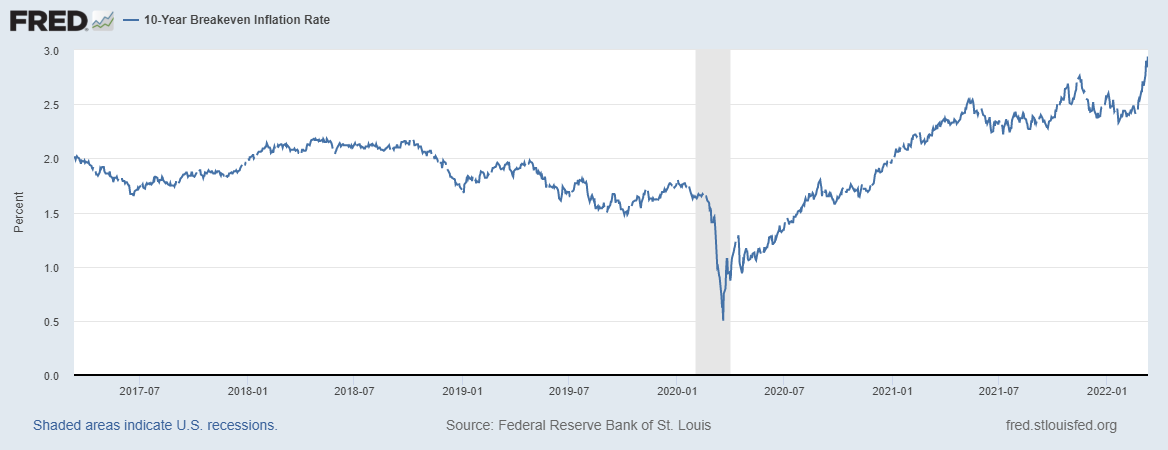

When you combine Russia-Ukraine commodity shortages with Chinese supply chain snarls, it’s a recipe for even more inflation. Hence, perhaps it’s unsurprising that inflation expectations have started to shoot up again:

Let’s take a moment to appreciate what this chart means. This means that markets are now betting that inflation will run at a 3.5% annual rate for the next 5 years. That’s far above the Fed’s target of 2%.

And even worse, 10-year inflation expectations are now rising too.

This means investors are now betting on their belief that inflation will still be significantly above target in 2032.

And remember that not all inflations are created equal. The inflation of 2021, though exacerbated by supply chain problems (and perhaps by the early retirement of older workers), was still mostly demand-driven — people had more money to spend due to Covid relief spending and pent-up savings from 2020. This pushed up wages at the low end, so that even if the middle and upper classes were seeing their real wages drop, working-class folks were making real gains. And the economy as a whole was booming, with unemployment near record lows and labor force participation recovering rapidly.

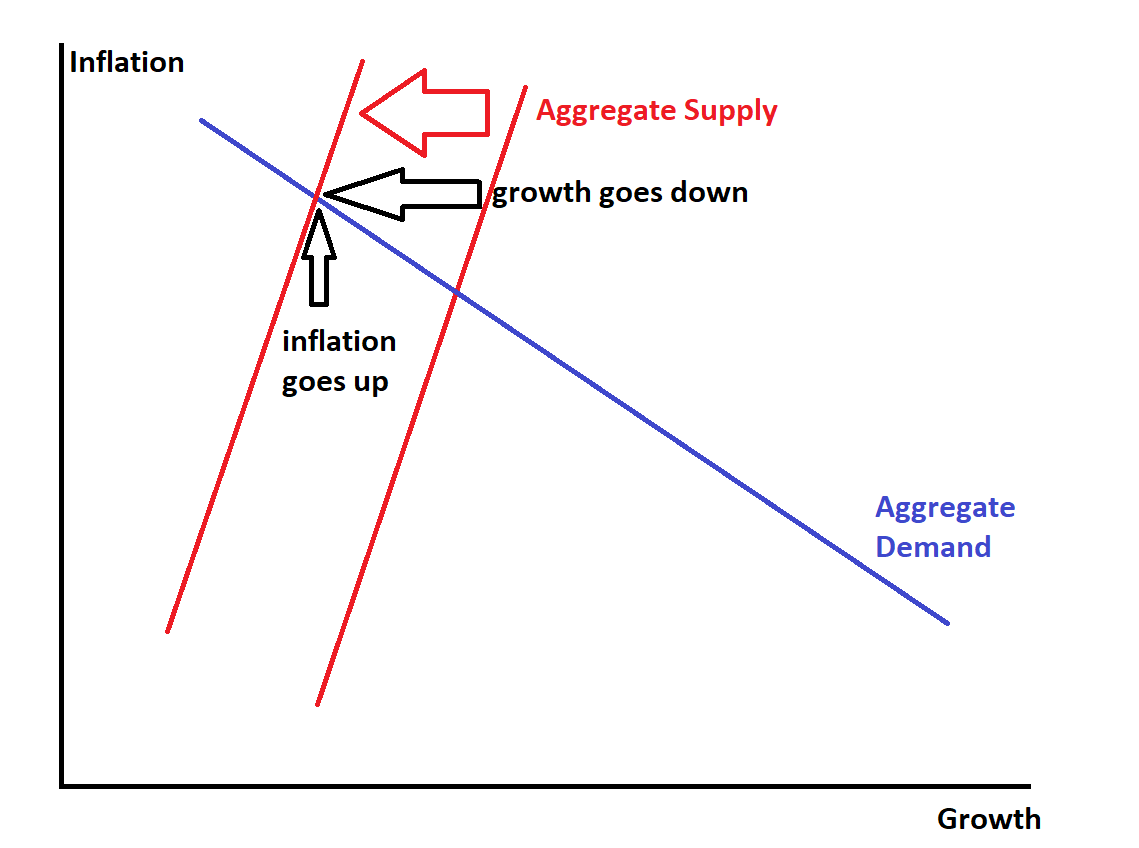

Inflation driven by commodity price shocks, in contrast, would likely be closer to the situation in the 1970s. Lots of businesses use oil and gas, and more expensive inputs will mean lower economic growth even as prices rise. That’s called stagflation. In a simply model of aggregate supply and aggregate demand, it looks like this:

So there’s a good chance that this new bout of inflation could be more painful than the last, because it’s likely to come without the upside of booming employment and rising low-end wages.

And there’s another reason this inflation should have us worried: The Fed.

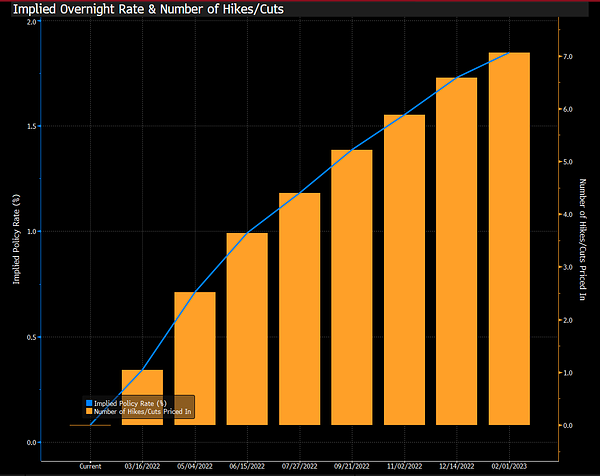

A decade of persistent high inflation would probably be enough to get the Fed to pull a Paul Volcker — to raise interest rates so high that the economy comes crashing down, millions lose their jobs, and inflation expectations get reset to a permanently lower level. But the question is whether the Fed will do anything like that right now. Expectations for Fed action have increased a bit:

But it’s important to put this in perspective. Markets are expecting the Fed to raise rates, but only to 2%. That’s still very low in historical terms — less than half of where rates were for most of the 90s, and far less than the 19% that Volcker unleashed:

So people still don’t think the Fed is ready to drop the hammer on the U.S. economy. But even a mild rise in rates could have some effect — Yellen’s announcement of gentle hikes in late 2015, which ultimately topped out at only 2.4%, still probably triggered the mini-downturn of 2016 (which may have helped Trump win that election). And once the China disruptions are factored in — and especially if the lockdowns get even worse — rates could end up being more than 2% by this time next year.

Will this cause a recession? It’s notoriously hard to predict recessions until they’re right on top of you. Economists have a few tools available to predict financial crises a few years in advance, but this recession, if it comes, will be the Fed-induced variety rather than the 2008 type. The stock market — a mediocre predictor of recessions — seems stuck on the same mild downturn that it’s been in since the start of this year, and hasn’t really reacted much yet to the war or the bad news from China. Goldman Sachs now says there’s a 35% chance of recession, but I also wouldn’t put too much stock in their predictions either. These things are just too hard for anyone to forecast with a high degree of certainty.

Even if inflation doesn’t prod the Fed to cause a recession, it’ll still have negative effects on both wages and on public sentiment. I doubt this is the beginning of a catastrophic hyperinflationary spiral — the Fed will do what it needs to do to stop that from happening. But falling real wages, along with slowing economic growth, could be quite a toxic brew — especially if you’re a Democrat up for reelection this year. And 2024 could be even scarier, given the high likelihood that Trump will be the GOP nominee.

So the Biden administration should be taking whatever steps it can to stem the inflationary tide, especially concerning oil prices (I like Employ America’ plan here). But beyond that, it’s not clear what we can do without hurting the economy even more. We may simply have to buckle up and prepare for a bumpy ride.

Update: It looks like the falloff in Chinese demand — or at least the expected falloff — is canceling out some of the oil price spike from the Russia sanctions. That’s good news for the U.S., and bad news for both China and Russia.

So in layman's terms: the next year or two might suck, but hopefully we'll come out of this with somewhat minimal damage for the everyday US citizen?

Noah, I feel like we are about to witness a BOOM in private and public investment with the goals of onshoring supply chains and decarbonization. Equiv. to a sort of war mobilization. How would that affect the 'stag' part? I'll assume bad for the 'flation' part b/c of ongoing (accelerating?) supply problems.