This is the penultimate post in my short series about China’s economy in 2023. As usual, I’ll have a post where I link to the whole series.

In the 2010s, everyone knew that China was “the future”. In the 2020s, it feels more like the present. China has fully arrived on the world stage. Around the world, people’s houses are full of Chinese products, they spend their time watching videos on a Chinese app, and many of them now drive Chinese cars. China makes the best drones and the best trains. The internet is full of videos of the country’s luminescent skyscrapers, cavernous train stations, and futuristic payment systems. Chinese researchers dominate the journals, and are believed to lead the world in many areas of technology. No one questions the fact that the PRC is now one of the world’s great military powers, with the U.S. as its only real rival.

We thus have the privilege of seeing a great civilization at its peak. There’s something awe-inspiring about it, but for me, something wistful as well. How much greater would China’s peak have been if Deng Xiaoping had sided with the Tiananmen Square protesters, and liberalized China’s society in addition to its economy? How many great Chinese books, essays, video games, cartoons, TV shows, movies, and songs would we now enjoy if it weren’t for the pervasive censorship regime now in place? How much more would the people of the world have learned from Chinese culture if they could travel there freely and interact with Chinese people freely over the internet? Without a draconian autocrat like Xi Jinping at the helm, would so many Chinese people be looking to flee the country? Would the U.S. and China still be friends instead of at each other’s throats?

But anyway, that’s a bit of a tangent. The key fact is that China’s meteoric rise seems like it’s drawing to a close. Already the country is not growing much faster than the G7, and as the ongoing real estate bust weighs on the economy, even that small difference may now be gone. The country’s surging auto industry is a bright spot, but won’t be big enough to rescue the economy from the evaporation of its primary growth driver.

Yes, for those who were wondering, this does look a little bit like what happened to Japan in the 1990s. The basics of rapid aging and a popped real estate bubble are both there, but there are some additional similarities that people may not know about. For both countries, there came a point where export manufacturing stopped being the main driver of growth — for Japan, after the Plaza Accord, for China after the appreciation of the yuan in the mid-2000s and the global financial crisis shortly afterward.

China’s drop was much much bigger; the Japan of the 80s was never the export machine people believed it to be. Both countries turned to investment in real estate and infrastructure as a replacement growth driver — although again, China did this much more than Japan did. Essentially, China did all the the things we typically think of Japan as having done 25 years earlier, but much more than Japan actually did them. It remains to be seen if China will copy Japan’s biggest post-crash mistake — keeping “zombie” companies alive with cheap loans.

In any case, it seems likely that China’s growth will now slow to developed-country levels, or slightly higher, without much prospect for a sustained re-acceleration. At this point, with the economic value of additional real estate and infrastructure so low, a re-acceleration would require a massive burst of productivity growth, which just seems unlikely. That means China’s catch-up growth only took it to 30% of U.S. per capita GDP (PPP). Even if it manages to climb up to 40%, that’s still a fairly disappointing result — South Korea is at 71% and Japan at 65%. (China’s defenders will say that it’s harder to grow a big country than a small one, but…well, the U.S. is a fairly big country as well.) This is another example of China’s peak being both awe-inspiring and strangely disappointing at the same time.

China is unlikely to decline soon

The next question on a lot of people’s minds, at least in the U.S. and in Asia, will be: Now that China has hit its peak, will it decline? And if so, how much and how fast?

Nations don’t really “peak and decline” like they used to in pre-industrial days. When the Roman Empire declined, it got a lot poorer. But in the modern economy, countries that decline in relative terms, and in geopolitical power, often get richer — some people would say that the Victorian or Edwardian era was Britain’s “peak”, and yet the average British person is 5 times as rich as in 1900. So when people contemplate Chinese decline, they’re not asking whether its economy will shrink; they’re asking whether its relative economic dominance and geopolitical importance will decrease.

If we just casually pattern-match on history, the answer would probably be “not for a long time”. Most powerful countries seem to peak and then plateau. Britain ruled the waves for a century. U.S. relative power and economic dominance peaked in the 1950s, but it didn’t really start declining until the 2000s. Japan and Germany had their military power smashed in WW2, but remained economic heavyweights for many decades afterwards. Russian power had a second coming in the form of the USSR.

There’s one main argument that people make for a quick Chinese decline: rapid aging. But while I don’t want to wave this away, I don’t think it’s going to be as big a deal as many believe — at least, not soon.

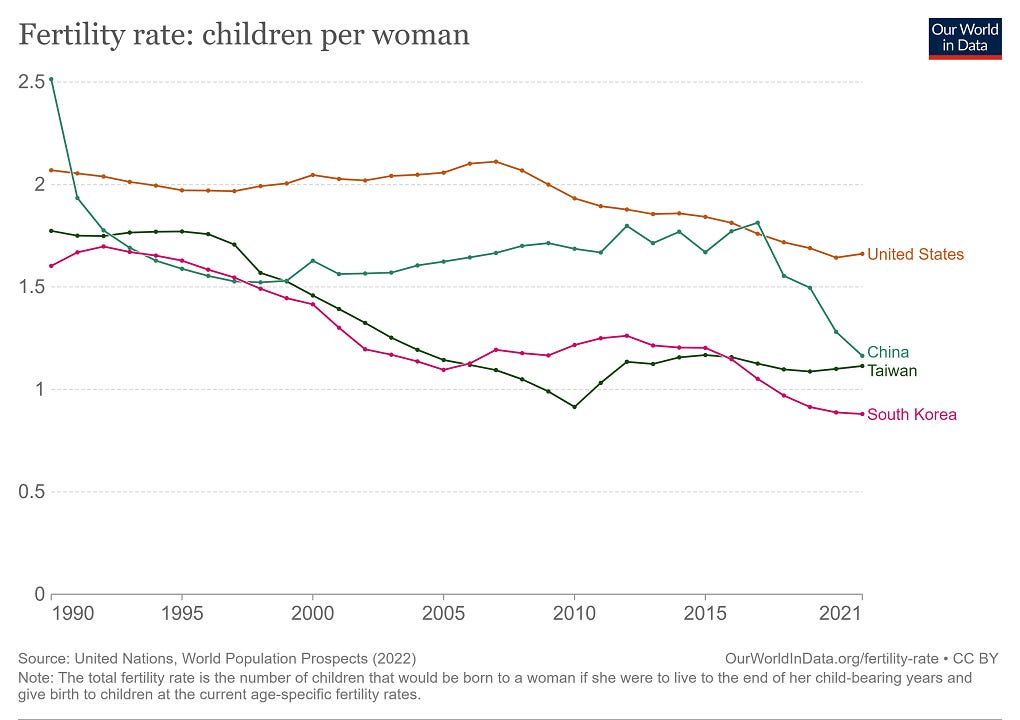

It’s undeniable that China’s demographics are pretty stark. The total fertility rate has been low since even before the one-child policy was implemented, but recently it has taken a nose-dive. Two years ago, the UN put it at 1.16, which is 40% lower than the U.S. and 22% lower than Europe (both of which have their own fertility issues). China’s fertility looks more like that of Taiwan, and could be headed in the direction of South Korea:

And China’s population structure is also contributing to an especially rapid birth collapse. The country’s total population only started shrinking this year, but its young population started falling sharply 20 years ago, due to the echo of low fertility in the 80s. The most common age for a Chinese person is now about 50 years old, with another peak at 35:

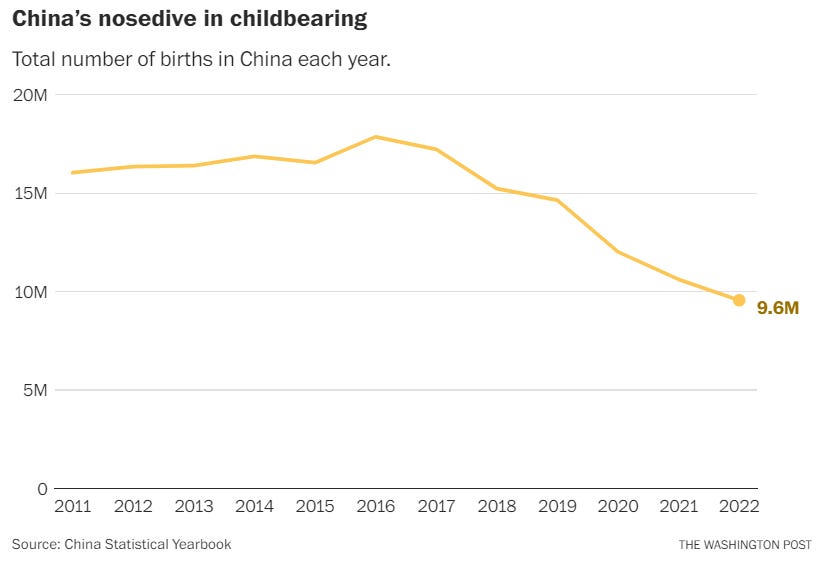

As a result, there are suddenly many fewer Chinese people able to bear children, which is why the actual number of births in China has fallen by almost half since 2016:

These dramatic statistics have led a number of people to predict that China’s demographics will send it into relative decline. More darkly, some geopolitical analysts have raised concern that China’s demographics may drive it to launch a major war in the near future, before its power wanes.

Now, I don’t have any idea whether China’s leaders will fall victim to this type of thinking — as we saw with Germany in the World Wars, powerful countries can make big mistakes like this. But what I do think is that demographics aren’t actually going to force Chinese power or wealth into rapid decline over the next few decades.

The first reason is that power is relative, and China’s rivals have demographic issues of their own. The U.S., Europe, India and Japan all have higher fertility than China, but still below replacement level. Those demographic issues can be staved off to some degree by mass immigration, but only to some degree, and only if the countries can overcome the associated internal political hurdles.

Second, demographics won’t take away China’s biggest economic advantage, which is clustering and agglomeration effects. Asia is the world’s electronics manufacturing hub. It’s also by far the most populous region in the world, giving it the biggest potential market size. Those two factors mean that even as China’s population continues to fall, it’ll be situated at the center of region that’s growing in both economic and (for now) demographic terms. And China will act as a key hub for that region, in terms of trade, supply chains, investment, and so on. China is shrinking, but Asia is not.

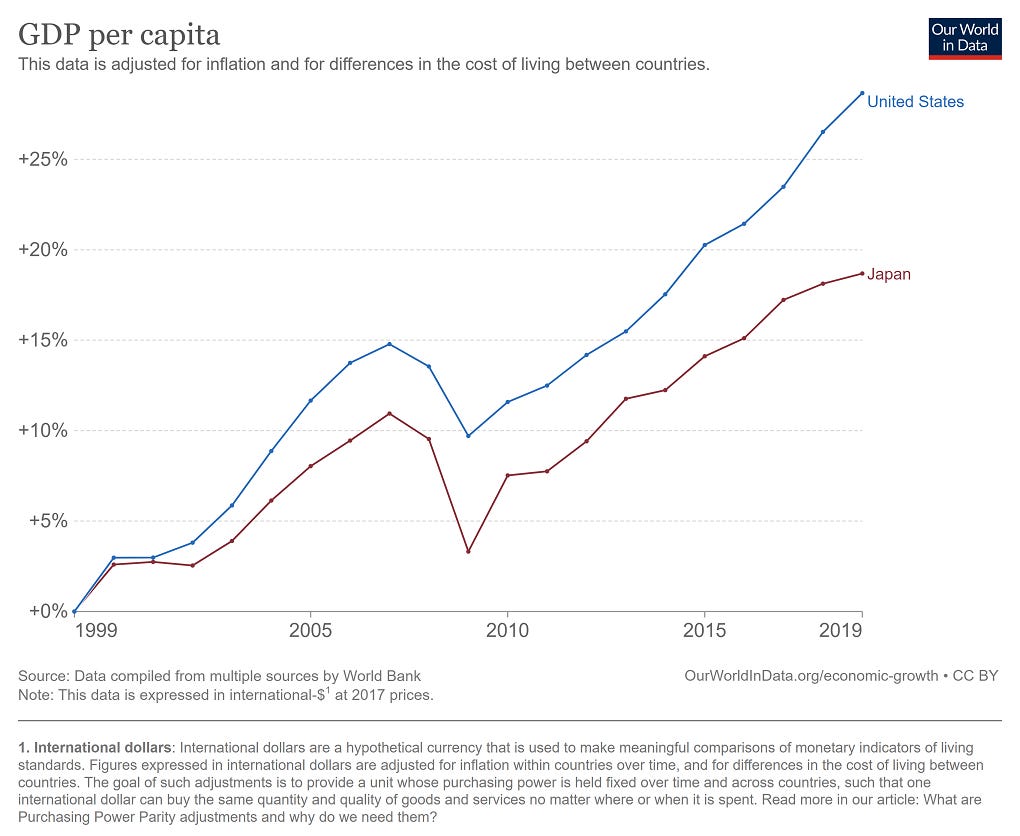

And third of all, evidence suggests that population aging is really more of a persistent drag than a crisis or disaster. Let’s compare Japan, one of the world’s most rapidly aging societies, with the U.S., which has aged only slowly. From 1999 (roughly the end of Japan’s “lost decade”) through 2019, Japan’s share of workers over 65 increased by about 12.06 percentage points, while the U.S.’ share increased by only 3.39 percentage points — a difference of 8.67 percentage points:

At the same time, Japan’s economy underperformed the U.S. economy by about 10 percentage points in cumulative terms:

So just dividing the second number by the first, we’d find that every percentage point of the senior population share that China gains relative to other countries might reduce its relative economic performance by about 1.15%. That’s not a huge number.

Now, if we look at the research, we find some estimates that are much larger than this — for example, Ozimek et al. (2018) look at specific industries and specific U.S. states, and find an effect on productivity that’s three times as large as the total effect on growth that I just eyeballed above. Maestas et al. (2022) look at U.S. states, and also find a larger effect. But Acemoglu and Restrepo (2017) look across countries and find no effect at all.

On top of that, there are plenty of things a country can do to mitigate the effects of aging. One is automation. China is automating at breakneck speed, while in the U.S., top technologists and intellectuals talk about limiting automation in order to protect jobs. A second is having old people work longer; China, which now has higher life expectancy than the U.S., is well-positioned to do this.

Finally, aging will prompt China to do something it really needs to do anyway: build a world class health care system. In addition to solving China’s unemployment problems, this would help rectify the internal imbalances that Michael Pettis always talks about, shifting output from low-productivity real estate investment toward consumption.

So while I expect aging to exert a persistent drag on China’s growth over the next three or four decades, it doesn’t seem likely to be a crisis that will push the nation into rapid relative decline. And if not aging, the only other big dangers to China are war and climate change. The harms of climate change will be pretty widely distributed around the globe, so really that just leaves war as the thing that threatens to knock China off the peak of its relative power and wealth. War was the big mistake that Germany made a century ago, so let’s hope China doesn’t follow in its footsteps.

Thus I think the most likely outcome is that China sits at or near its current peak of wealth, power and importance through the middle of this century at least.

If China is the present, where is the future?

Investors, diplomats, entrepreneurs, and dreamers of all types naturally want to look to the region of the world that represents “the future”, so they can get in on that future — whether by making money, crafting alliances, or just experiencing the thrill of a rising society. In the 2000s and 2010s that place was China — nowhere else on Earth could match its energy, ambition, and determined optimism.

Now that excitement will largely be gone from China, except in a few pockets. Where will it go? What country or region of the world will be the next place that feels like the “future”?

In a pair of articles from earlier this year, The Economist makes a strong case for something they call “Altasia”. This is basically all of East and South Asia except for China and a few small unstable or highly repressive countries.

Together, Altasia has more people and arguably more technical expertise than China. And it’s the only alternative location for the Asian electronics supercluster.

The problem is that Altasia isn’t actually “together” — like BRICS, it so far exists more as a marketing buzzword for Western investors than as an actual economic bloc. The grouping is bifurcated between rich, slow-growth countries like Japan and Korea, and poor up-and-coming countries like India, Indonesia, and Vietnam.

To realize its full potential, Altasia will need integration — it will need some way to get Japanese and Korean and Taiwanese investment and technology to the vast labor forces of India, Indonesia, and the rest. The Americans, Europeans, and Chinese will also be looking to expand there, both for the cheap production costs and for the vast market opportunities. And to top it all off, the U.S. and its allies will be looking to “friend-shore” their critical supply chains from China to Altasia, especially in electronics.

The story of whether and how that complex web of investment, tech transfer, and trade develops will be the next great story of globalization.

But I think the very complexity of Altasia will lead to its own sort of adventure and excitement. We haven’t seen an entire region industrialize all at once since Europe in the late 1800s (the closest thing being the Asian “tiger economies” of the 80s and 90s, which was really just Altasia’s predecessor). This will be much bigger. Investment and trade and diplomatic links will be flying back and forth between these various countries at a frenetic pace. Everyone will be trying to figure out who builds what where, where they source from, and where they sell to. Eventually, cultural links will follow.

And for Western companies looking for new markets, Altasia will potentially be more exciting than China ever was. The Chinese market delivered riches to some, but the government banned some products (especially internet services) and stole the technology used to make others. Ultimately, China’s billion consumers turned out to be a mirage for many. The economies and societies of Altasia, in comparison, are much more open to foreign products.

And in the poorer countries of Altasia — India, Indonesia, Vietnam, Bangladesh, Philippines, etc. — there will be the heady excitement of industrial development. It will be their turn to build highways, their subways, their gleaming forests of apartments and office towers. It will be their turn to buy cars and big-screen TVs, go out to eat, go dancing at clubs, and send their kids to college. Developing Altasia will be a damn exciting place to be in next three decades.

Great summary. Over here in HK, there seems to be a rapid frenzy to bring Chinese-style consumption, infrastructure, investment, supply chains and international market expansion to Southeast Asia. Chinese people are moving to Indonesia to teach Indonesians how to sell Chinese goods despite not speaking the local language, for example.

https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2023-07-05/tiktok-shop-emerges-as-amazon-rival-powered-by-indonesian-boom

Indonesians do not see this as a national security issue. Meanwhile, my father, who's all set to retire from a factory outside Jakarta, remarks that Chinese companies and engineers are trying hard to get them to share his IP on developing dyes so that they can produce them at scale in an environmentally compliant way for the Chinese and Indonesian market.

Altasia - India is the new growth engine and it will likely be dominated by US and Chinese VCs/PEs.

What blows my mind away is that in 1978, around the time of China's opening to the world, India and China were equal in per capita income terms, and as far as the lives of the average citizen is concerned, the Chinese had it much worse after the horrors of the great leap and cultural revolution. Whatever one's views about China's political system, their exponential dizzying rise is still humanity's greatest achievement!