At least five interesting things for your weekend (#24)

Economists had a good 2023, degrowthers promising growth, the troubles in the humanities, U.S. redistribution, and defense production

Happy New Year! I’m back from Taiwan, which turns out to be a really great place to go for New Year’s, given the perfect weather and city-wide celebrations. December turns out to be the perfect time to go to Taiwan. The weather is really nice (the island is subtropical so it ranges from slightly warm to crisp and cool), there are no big family holidays to interrupt the social calendar, and there are bunch of festivals and events and parties around that time. Among my little social circle, Taiwan December is becoming a bit of a tradition, and I think others should copy us.

Anyway, it’s time for the first roundup of 2024! No podcast episodes this week, since I was out of town and didn’t record any. So, on to our five interesting things.

No, economists didn’t really have “a dreadful 2023”

I saw a curious article in The Economist the other day, arguing that economists, as a group, had a “dreadful 2023”. There were basically two reasons given for this claim. First, U.S. inflation fell without a recession, defying many forecasts. But also, there were a number of research findings in the field that challenged other research findings:

Auten and Splinter published new estimates that show no rise in inequality over the past few decades.

Greaney challenged Hsieh and Moretti’s estimates of the benefits of allowing greater density in superstar cities. (I discussed this one in an earlier roundup as well.)

Ward published new estimates of intergenerational mobility in America that showed an increase in relative mobility over time, contrary to some earlier estimates that showed a drop. This is largely due to increased mobility for Black people and other minorities.

Moore, Olney, and Hansen showed that fentanyl deaths depend on proximity to fentanyl supply, and that this is not related to the geography of “deaths of despair” found by Case & Deaton and others.

These are all interesting and important research findings. It’s not at all clear to me why they represent a failure for the field of economics.

This is just how science is supposed to work. New research comes along and improves on old research, often overturning old conclusions and debunking old beliefs in the process. Do the Economist’s writers imagine that researchers in microbiology or neuroscience or materials science always find the right explanation for a phenomenon on the first try? When researchers in the natural sciences come along and present new data that shows us why we were wrong about something, we hail it as a triumph; why should we lament it as a failure in the social sciences?

The fact is, all of these four new pieces of research represent healthy debate and progress toward understanding our world. If these four papers are any indication, economists had a great 2023.

A recent Brookings analysis of the debate between Auten & Splinter and Piketty et al. shows that the truth probably lies in between the two estimates — inequality has increased more than the former think, but less than the latter claim. (This was my takeaway as well.) This means that both sets of findings are important and useful, since they represent upper and lower bounds on the truth, and since the differences between their methodologies clarifies the sources of inequality.

Greaney’s challenge to Hsieh & Moretti — which I discussed in a previous roundup — is going to mean that fewer people lean on the work of the latter when arguing for greater urban density. But that’s fine, since there’s a ton of other work showing that density is good, and it was never a good idea to rely on just one paper with a big outlier result.

Ward’s estimates on mobility are a great reminder that we need to consider the experience of minorities in the story of the American economy.

And Moore et. al. don’t even try to debunk the Case-Deaton “deaths of despair” theory; in fact, they accept it as true, and show that their finding on the effects of fentanyl supply is in addition to whatever Case and Deaton find.

(Meanwhile, the Economist article also discusses the possible fraud by two prominent psychologists. But although one of those psychologists, Dan Ariely, calls himself a “behavioral economist”, the potentially fraudulent research in question is on the topic of dishonesty, and has little if any connection to economics.)

So no, the flurry of challenges to high-profile results doesn’t represent a crisis in economics. At worst, it represents a reminder to economics journalists not to instantly overhype research findings, and instead to wait for the academic community to discuss and challenge those findings.

The Economist article also draws a very unwarranted conclusion from all this:

Another lesson is that disdain for economic theory in favour of the supposed realism of empirical studies may have gone too far.

Economic theory is important, and certainly has its proper uses. But using the idea of theory as a recourse to avoid having to evaluate thorny empirical disputes is not one of them.

If what you want from economists is unchallenged verities and the illusion of knowledge, then sure, you might as well recoil from empirical disagreements and retreat to the safety of theory. But if you want real knowledge instead of the comforting illusion of knowledge, then you’re going to have to get over your fear of seeing researchers contradict one another and get things wrong. Scientists aren’t sages who dispense truth from on high. Real knowledge is difficult and messy to produce, and there are often missteps and mistakes and blind alleys. Journalists need to get used to that.

Degrowthers now promise growth

The degrowthers lost the first round of the public relations battle. Despite getting copious social media attention and feeding off of the general unrest of the 2010s, they failed to persuade anyone important to embrace their agenda to even a small degree. American activists, realizing that Americans would never accept impoverishment, instead promised radical abundance through things like the Green New Deal. Meanwhile, the UK, whose recent economic outcomes look uncomfortably like degrowth, is angry about the stagnation of living standards.

At some point, the degrowthers realized that “let’s all be poor” is not a particularly effective sales pitch. So, with an impressive display of the self-marketing skill that put them on the map in the first place, they pivoted. The new line is that degrowth will somehow make rich-world people even richer.

This new sales pitch was prominently on display in a December 2022 comment in Nature by some of the usual degrowth suspects. The subheader of the piece is: “Wealthy countries can create prosperity while using less materials and energy if they abandon economic growth as an objective.” The article explains:

It is necessary to ensure universal access to high-quality health care, education, housing, transportation, Internet, renewable energy and nutritious food. Universal public services can deliver strong social outcomes without high levels of resource use…[We must] train and mobilize labour around urgent social and ecological objectives, such as installing renewables, insulating buildings, regenerating ecosystems and improving social care.

Degrowth can make these extravagant promises only by pretending that words suddenly mean the exact opposite of what they used to mean. Creating prosperity is growth. That is what growth is. That is what it means. That is its definition.

In the old days, degrowthers used to argue that economies couldn’t grow without increasing their resource usage. As it quickly became apparent that this was wrong, they pivoted to redefining growth as resource usage. But that’s not the definition of “growth” that any economist uses, or that’s reflected in national statistics. In fact, rich countries have been providing more GDP with less resource use for years now, and poor countries are starting to follow in their footsteps. When you provide more GDP with less resource use, that is growth.

So yes, degrowthers are promising growth, and simply calling it by other names. In a recent op-ed, Jason Hickel, degrowth’s chief evangelist, rather hilariously uses the word “acceleration” to describe the mobilization of “massive amounts of labour, factories, materials, engineering talent, and so on.”

This represents a necessary evolution of the degrowth movement away from real proposals for self-inflicted catastrophe and toward semantic play. The next evolution will be toward “rediscovering” ideas that pro-growth environmentalists have been talking about and implementing for years — dematerialization as a way of enhancing sustainability, the usefulness of green industrial policy and carbon taxes to shift the economy toward more sustainable activities, and so on. The one constant, of course, will be that they’ll always reserve the word “growth” to describe some negative trend, in order to make it seem like they weren’t just barking up the wrong tree at the beginning.

Why the humanities are declining

Back in 2011, when I was in graduate school, I remember asking some friends in the humanities what the social purpose of their job was. I was just teasing, but their answer was interesting. They said that the purpose of the humanities was activism — pushing politics in an egalitarian direction by uplifting the voices of the marginalized. In 2016 when I asked another humanities scholar friend the same question, she told me that the purpose was empathy — giving people the ability to understand people from different backgrounds and perspectives.

To me, those are two very different justifications, and the latter sounds much more like something I’d want my tax dollars to support. But literary scholar Tyler Austin Harper argues, in a recent article in The Atlantic, that both of these aims are too nakedly political. His central thesis is that the politicization of the humanities is a response to economic forces — a lack of jobs and funding in the field:

If the humanities have become more political over the past decade, it is largely in response to coercion from administrators and market forces that prompt disciplines to prove that they are “useful.” In this sense, the growing identitarian drift of the humanities is rightly understood as a survival strategy: an attempt to stay afloat in a university landscape where departments compete for scarce resources, student attention, and prestige…[A]dministrative incentives and financial pressures have forced the humanities to contort themselves in their own defense…

In a brave new world where every major must prove its worth to its debt-saddled “student-customers,” the humanities have a hard time mounting a credible case that their disciplines catapult graduates into six-figure salaries. What humanities departments can offer their young charges—who grow more progressive by the year—is the promise that their majors can help them understand power and fight for equality.…Instead of trying to prove that the humanities are more economically useful than other majors—a tricky proposition—humanists have taken to justifying their continued existence within the academy by insisting that they are uniquely socially and politically useful.

This seems unequivocally correct. At this point everyone realizes that American college kids are stampeding away from the humanities and toward degrees like computer science that they think will give them a greater chance of getting a job and a good salary after graduation:

Nothing is going to halt that shift except for a sustained restoration of economic confidence and optimism in the U.S. that will make kids feel financially secure enough to go study the humanities for fun. I’m in favor of that, but how to do it is a thornier problem.

Thus I’m pessimistic that Harper’s accurate diagnoses will lead to any sort of actionable plan to revive the humanities. Some scholars seem to hope that progressive politics will simply triumph in the U.S. so overwhelmingly that the government will be willing to lavish the humanities with funding. This is highly unlikely. Some moderates, in contrast, hope that moving the humanities toward a more moderate politics will get the GOP off their back. This also seems unlikely — I don’t think Republicans would even recognize the change — but it also wouldn’t address students’ worries that an English major won’t get them a good job. And that worry is the fundamental problem.

What I think academics need to reckon with is that while humanities research was always a labor of love, humanities education used to basically be a finishing school for elites — a way of inculcating future government and business leaders with the cultural knowledge they’d need to prosper and succeed. The shift toward an economy where success depends more on technical skills and less on backslapping deal-making than before, and the opening up of the elite to broader entry and competition, has put an end to the days of the insular East Coast WASPocracy that the humanities were initially designed to support.

So I don’t have any good answers for the humanities. But whatever the solution is, it seems like it has to involve providing students with the soft skills that are increasingly important in the modern economy. And though I don’t know for sure, my hunch is that those soft skills aren’t going to involve starting activist campaigns in the company Slack.

The U.S. is not a plutocracy

In the 2010s, in the wake of Occupy Wall Street, the Great Recession, and Bernie Sanders’ surprising outperformance in 2016, the dominant economic narrative among Democrats became a left-populist one. America had left its poor and middle classes to rot, refusing to give them European-style welfare states thanks to rich people’s stranglehold on politics. Inexorably increasing inequality and a pervasive lack of opportunity were the clear result of neoliberal orthodoxy and the moneyed interests behind it.

This narrative wasn’t entirely false, but it was overstated. Now, with the economy on a solid footing and the social unrest of the 2010s slowly fading, people are starting to push back against the more extreme versions of the left-populist story. The papers by Auten and Splinter (2023) and Ward (2023) are two such efforts. Auten and Splinter overstate their case with some extreme assumptions, and Ward works with historical data that can get pretty murky. But both are important works that lend needed nuance to the 2010s-era stories about inequality and class immobility.

To that list, I’d like to add Coleman and Weisbach (2023). They find that the American fiscal system has become substantially more progressive over recent decades:

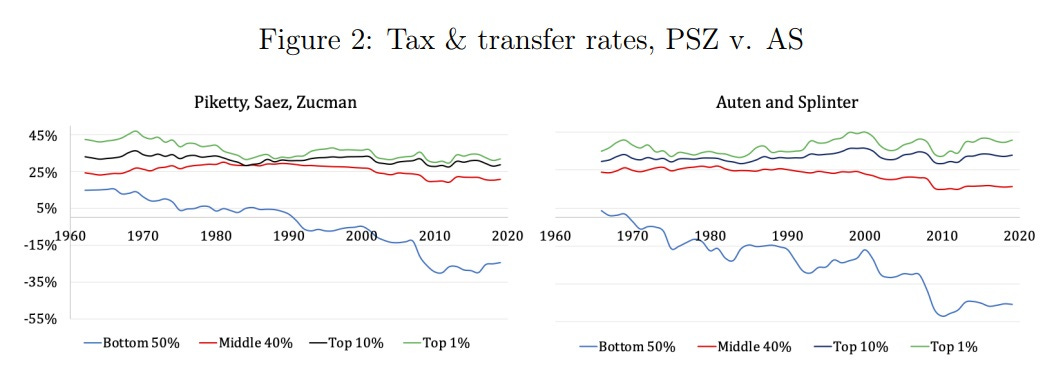

We examine changes in tax progressivity over time. …[W]e compare the results from three different publicly available datasets, those from Piketty, Saez, and Zucman (2018), Auten and Splinter (2023) and Congressional Budget Office (2023)…[A]ll three datasets show that the tax system has become more progressive and more redistributive over the last several decades, with much of that change occurring in recent years. This increase in redistribution is driven primarily by an increase in transfers to households in the bottom half of the income distribution which is missed by a focus on the top 1%.

When you combine taxes and transfers, they find, the bottom 50% of the U.S. distribution gets out more than it puts in (as Mitt Romney noted in his 2012 presidential campaign). And the amount they get out has gone up over time:

The CBO finds even more redistribution.

This is consistent with other papers that I’ve been citing for a while, and it’s consistent with a bunch of other papers that Coleman & Weisbach find in their literature search. It is not consistent with the story that the U.S. has become less redistributive due to the Reagan and Bush tax cuts and Clinton’s welfare reform. Yes, the U.S. has become a more unequal place over the past few decades, but our government has been actively fighting against that inequality. And the biggest jump in progressivity came under Barack Obama, as a response to the Great Recession; the Tea Party Congress did not manage to reverse the change, nor did Trump.

This should cast doubt on the notion, cherished on the Left and accepted by many progressives, that the U.S. is a plutocracy whose economic policies are driven by the desires of the rich. That notion always rested mostly on faith — the research that seemed to support it was basically just one single paper with highly questionable methodology.

Instead, I would like to direct you to Marechal et al. (2023), who look across various countries and find that redistributive policies are correlated most strongly with the desires of the poor, not the rich. The fact that the U.S. redistributes a bit less than European countries is probably due more to various sociocultural factors than to the malign influence of the rich.

This is just another piece of the 2010s narrative that we need to re-examine.

The U.S. needs more defense production

A few months ago I wrote one of my more popular posts, and certainly one of my scariest. It was about how the U.S. is unprepared for a war with China that could break out at any moment, and how our lack of preparation would give China a good chance of beating us:

Now, in a recent op-ed for DefenseNews, Wilson Beaver and Jim Fein give some more data on just how bad it is:

The U.S. military is already tasked to do more than it has been equipped to do. At present, our armed forces do not have the munitions needed for a contingency in the Indo-Pacific region, and we certainly aren’t producing enough munitions to sustain operations in all three theaters at once…

For example, Ukraine is expending between 110,000 155mm shells per month…Even after doubling shell production, the U.S. produces only 28,000 per month…

Wargames have repeatedly shown that the U.S. will run out of critical munitions only eight days into a high-intensity conflict with China over Taiwan…The Navy’s annual procurement of Tomahawk missiles and MK 48 torpedoes, for example, falls woefully short of the needs of the fleet. If all 73 Arleigh Burke-class destroyers are available, the Navy’s FY22 procurement of 70 Tomahawks only allows each to launch 0.96 Tomahawks. If all 22 Virginia-class submarines were available, the 58 MK 48 torpedoes procured by the Navy that fiscal year would not fill their 88 torpedo tubes even once.

Dipping into U.S. military inventory does not make the situation much better. An educated guess is that there are about 4,000 Tomahawks in the Navy’s possession…[T]he Navy’s Tomahawk inventory is so low that it likely can’t reload all its ships even once.

Beaver and Fein’s suggestion is to switch to long-term contracts that give defense producers the guaranteed demand that they need in order to risk ramping up production. This will require increased defense spending, which will make both progressives and conservatives mad — progressives because they don’t like spending money on the military, conservatives because they don’t like spending money on anything when a Democrat is in the White House.

But it has to be done. The alternative is to sit there and bicker with each other while catastrophe looms. We’re not taking this nearly serious enough. I hate to end this roundup on a down note, but that’s the grim reality.

I studied chemistry in undergrad, but the classes I enjoyed the most by far were my humanities, maybe because it was a break from the grind of the undergrad chemistry sequence.

It's a little unfashionable, but I believe that the "finishing" aspect of humanities courses is underrated. My fellow STEM majors generally bellyached about having to meet their liberal arts gen ed requirements, but a good basic ethics course, a bit of literature, some history or basic anthropology goes a long way towards rounding someone out, and for some it opens a world they can explore and enjoy the rest of their lives.

CS Lewis's "The Abolition of Man" has a lot of these broad strokes correct. I think higher education got itself in trouble specifically when as an institution it stopped caring about moral/ethical formation. The result is a disintegration that results in engineers who can't be bothered to ask the Jurassic Park question to humanities undergrads that reject the notion of objective truth. (I exaggerate the margins to make my point more visible).

Always love the roundups!

Tbh if degrowthers now agree with mainstream opinion while still claiming to edgy and radical by playing silly language games, I think they can be safely ignored. Surely even if they "win" this vacuous non-argument, if they don't actually have a fundamental disagreement with the status quo then that victory would not have any material implications.