At least five interesting things to start your week (#38)

WW2 production; "Neopopulism"; fake science; desire modification; deregulation ideas

I had a list of about 10 things to write about in this roundup, but I gave up halfway through and turned half of them into ideas for longer posts, because I realized that short summaries didn’t do them justice. So here are the five that remained, which are no less interesting but which can be summarized more succinctly.

First, podcasts. This week’s Econ 102 episode is another rapid-fire Q&A session. Keep sending me any questions you have!

And this week’s Hexapodia episode continues my roasting of Brad DeLong. This time I challenge him to defend his argument, five years ago, that the baton of liberal policymaking should be passed to folks on the left:

Anyway, on to this week’s list of interesting things!

1. How America built the Arsenal of Democracy

The most important article you’re likely to read this week is Brian Potter’s post on how the U.S. built its incredible, world-beating aircraft industry in World War 2:

The amazing thing is that the U.S. slapped together this industry almost from scratch:

In 1937 the U.S. produced around 3,100 aircraft, most of which were small private planes. Prior to the war the value of aircraft made in the U.S. was about one-fourth the value of cans produced, and just 3.5% of the value of cars produced…

Producing the aircraft needed to win the war required a complete transformation of the aircraft industry. Between 1939 and 1944…the total weight of aircraft produced…increased by a factor of 64. In 1940, the airframe industry employed just 59,000 people; three years later that reached 939,000, with another 339,000 building aircraft engines…[B]y the end of the war aircraft engine factory floor space had increased from 1.7 million square feet to 75 million, and a single large engine factory encompassed more space than had been used by the entire pre-war engine industry.

How did the U.S. accomplish this incredible industrial feat? Potter identifies several key factors.

First was a steady source of demand. The demand came from Britain and France, which ordered warplanes in order to fight the Nazis, just before WW2 and during the war’s early years. That predictable demand allowed U.S. manufacturers to take the massive risks necessary to expand their factories by enormous multiples. The cash involved also helped U.S. aircraft companies fund this expansion directly.

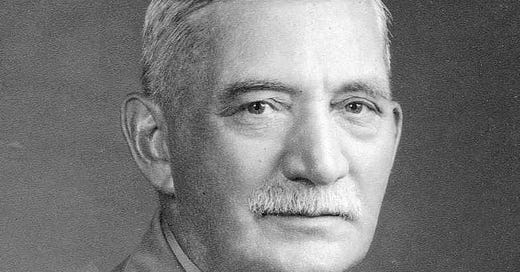

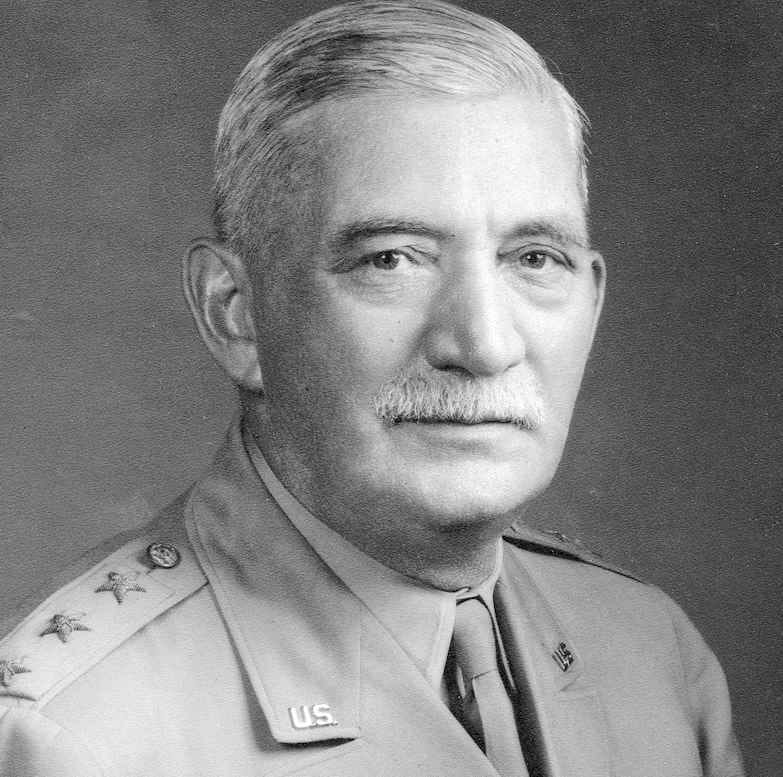

Another factor was plentiful financing, much of it from the Defense Plant Corporation, basically a big state-owned bank that financed defense production. The man who came up with the idea for the DPC was Bill Knudsen, a former exec at General Motors. Knudsen’s photo is at the top of this post, and he’s the protagonist of the excellent history book Freedom’s Forge. Importantly, Knudsen and his employers in the Roosevelt administration had the foresight to know a major war was coming, and to expand U.S. manufacturing by massive amounts before the bombs started falling.

A third factor was existing industrial capacity. The U.S. had tons of factories building cars, appliances, and so on, and many of these were quickly repurposed for aircraft and aircraft engine manufacturing. The U.S. also had lots of “primary industry” — aluminum smelters and such — that were able to furnish the aircraft industry with all the raw materials it needed.

A fourth factor was women, who filled around 40% of the labor needs of the massive aircraft factories. The famous Rosie the Riveter was based on these workers.

At the end of the post, Potter reveals what lessons he thinks modern America can learn from the amazing WW2 aircraft production effort:

[T]his success was highly contingent. The U.S. was woefully unprepared to expand its aircraft industry…Neither the government nor the industry had the organizational infrastructure in place to handle the scale up, or plans for creating it…It wasn’t until 1942, three years after Germany invaded Poland and France and Britain declared war on Germany in response, that U.S. aircraft production truly ramped up, and even this was only possible because of enormous early orders from Britain and France, and the work of far-sighted folks like Bill Knudsen who knew how long it took to scale up manufacturing operations…

World War II aircraft production shows that it's possible for a complex manufacturing industry to grow incredibly rapidly. But it also shows the limits of that scale up; that even in an emergency some things can only be accelerated so much, and success depends on what preparations have been taken beforehand.

This is obviously incredibly important for the U.S.’ current situation. We are not even remotely worried enough about a conflict with China, and as a result we’re not making anything remotely resembling the investments or the regulatory changes needed to fund a scale-up of our defense industry. Orders from Ukraine and Taiwan could be providing the steady demand for the U.S. defense industry to revitalize itself, but our government has been inconsistent with the necessary funding.

I worry that the only country learning the lessons of the U.S.’ World War 2 production miracle is China.

2. Does America have a new bipartisan “neopopulist” consensus?

David Leonhardt has an excellent article in the New York Times bringing together two important threads of what’s going on in the U.S. government these days:

The quiet increase in bipartisanship (which Matt Yglesias has called “Secret Congress”)

The shift in economic thinking from neoliberalism to industrialism

Leonhardt — correctly, in my view — identifies two factors behind this shift:

The rise of a China-led authoritarian power bloc whose power rivals or exceeds that of the U.S.

The seeming failure of decades of neoliberal policy to help the working class

Here are a few excerpts:

The very notion of centrism is anathema to many progressives and conservatives, conjuring a mushy moderation. But the new centrism is not always so moderate. Forcing the sale of a popular social app is not exactly timid, nor is confronting China and Russia. The bills to rebuild American infrastructure and strengthen the domestic semiconductor industry are ambitious economic policies…

The new centrism…is a recognition that neoliberalism failed to deliver…In its place has risen a new worldview. Call it neopopulism…

What other neopopulist policies might lie ahead? More legislation to address China’s rise and more industrial policy are possible. A bill to ensure that the United States has access to critical minerals like lithium and copper would qualify as both…Policies to help young families are plausible, too…

For decades, Washington pursued a set of policies that many voters disliked and that did not come close to delivering their promised results. Many citizens have understandably become frustrated. That frustration has led to the stirrings of a neopopulism that seeks to reinvigorate the American economy and compete with the country’s global rivals. As polarized as the country is, its two political parties are at least trying to respond to that reality, and they have found an unexpected amount of common ground.

I think this is a very perceptive and timely post. I do not think the term “neopopulism” will stick, mostly because of the negative connotations of the term “populism”. But I also think that “populism” is not quite the right frame for what’s going on here. Americans in general have a negative opinion of China, but many of the actual policy steps being taken to actually deter and balance China — things like export controls, semiconductor subsidies, expanded alliances, and so on — are actually elite projects rather than attempts to please the electorate.

Meanwhile, some of the most important bipartisan efforts — such as electoral count reform — have been done quietly, for the exact reason that if they drew the public’s attention, they would activate the partisan energies of both parties’ bases, making reasonable compromise that much harder. There’s a reason Yglesias calls it “Secret Congress” — much of the country is still in a bitter, fractious mood, and populist energies generally still push Congress toward division, gridlock, and intransigence.

Nevertheless, I do think Leonhardt’s article captures many important truths about where U.S. governance stands right now. The nation’s main challenge has shifted from internal battles over culture, identity and economic distribution to external threats, and some fraction of America’s leaders and the American people are slowly waking up to this fact. I also agree with his assessment that future bipartisan initiatives will likely include more industrial policy, more security-related policy, and policies to help children.

I also think there’s one more big one that he missed — housing policy. High rents are still causing widespread discontent throughout the nation, and government action is needed in order to combat the thicket of local barriers and restrictions that have kept housing from being built. There are some very encouraging signs that housing abundance could be a focus of bipartisan cooperation in the years to come — for example, the YIMBY Act that just passed the House of Representatives.

3. Fake science appears to be on the rise

Everyone knows about the replication crisis in science; now it’s time to meet the fraud crisis.

Recently I’ve seen a number of pretty disturbing stories about falsified research results. There were the famous cases of the honesty researchers who faked their data, the Alzheimer’s neuroscience falsification scandal that forced the president of Stanford to step down, and the room-temperature superconductor research that was also faked. But those appear to be only the tip of the iceberg:

The number of retractions each year reflects about a tenth of a percent of the papers published in a given year – in other words, one in 1,000. Yet the figure has grown significantly from about 40 retractions in 2000, far outpacing growth in the annual volume of papers published.

Retractions have risen sharply in recent years for two main reasons: first, sleuthing, largely by volunteers who comb academic literature for anomalies, and, second, major publishers’ (belated) recognition that their business models have made them susceptible to paper mills – scientific chop shops that sell everything from authorships to entire manuscripts to researchers who need to publish lest they perish.

Now there’s evidence that a large amount of cancer research has been faked:

Research integrity sleuths may have found a new red flag for identifying fraudulent papers, at least in cancer research: Findings about human cell lines that apparently do not exist. That’s the conclusion of a recent study investigating eight cell lines that are consistently misspelled across 420 papers published from 2004 to 2023, including in highly ranked journals in cancer research. Some of the misspellings may have been inadvertent errors, but a subset of 235 papers provided details about seven of the eight lines that indicate the reported experiments weren’t actually conducted, the sleuths say…And these papers may be the tip of the iceberg, [author Jennifer] Byrne says. Since January 2023, more than 50,000 scholarly articles about human cancer cell lines have been published. Byrne’s team identified a total of 23 misspelled lines but limited its analysis to eight mentioned in 420 papers to keep the workload manageable.

And the discovery of large amounts of falsified biomed research is now literally halting the publication of some academic journals:

Last year, a strange thing happened at Wiley…Its statement noted the Hindawi program, which comprised some 250 journals, had been "suspended temporarily due to the presence in certain special issues of compromised articles"…Many of these suspect papers purported to be serious medical studies…By November, Wiley had retracted as many as 8,000 papers, telling Science it had "identified hundreds of bad actors present in our portfolio"…A month later, in exquisite corporatese, the company announced: "Wiley to sunset the Hindawi brand."

Science, as an enterprise, depends on trust; scientists have neither the time nor the means to check every single result of every single researcher whose work they cite and build on. When large numbers of researchers commit outright fraud, the entire system is in danger, because at some point no one can trust anyone else’s results. You can’t stand on the shoulders of giants if you’re afraid those giants might be illusory.

And yet the incentives of modern science seem almost designed to encourage widespread fraud. The key metrics for success in science are 1) publications in peer-reviewed journals, and 2) citations of those publications. And as Goodhart’s Law tells us, all metrics will eventually be gamed. There are many ways to game the publish-or-perish system — p-hacking, specification search, citation rings, etc. Fraud might not be the easiest or safest of these. But it’s almost certainly the most damaging.

Peer review is a poor defense against fraud; even careful, diligent reviewers who might spot bad statistics or weak inferences will struggle to identify outright fakery. That leaves culture — a general feeling of pride in the integrity of the scientific system — as the front-line defense against fraud. There was never any assurance that this culture would remain intact as larger and larger sums of money got thrown at science.

This suggests that in order to maintain the enterprise of science, more “fraud police” will be necessary to catch wrongdoers. But it should also raise the question of whether researchers should be rewarded for publishing in high volumes. It might be better to reward quality over quantity.

4. The quiet rise of Desire Modification

What is the ultimate technology? In many classic science fiction stories, it’s faster-than-light travel, which would allow us to explore and perhaps colonize infinite new worlds. In others, it’s personality upload, which would allow us to create digital worlds to suit any and all of our desires. In yet others, it’s artificial general intelligence, which would be smart enough to give us anything we want.

But a few stories toy with an even stranger idea that might trump all of the above: desire modification, which would allow us to change our fundamental psychology. What’s the point of exploring or creating new worlds when we can change ourselves to be better suited to the world we already have?

Humanity has been trying to modify our desires for millennia, with things like meditation. More recently we’ve added drugs to the mix — antidepressants, anti-anxiety meds, etc. We’ve even experimented with deep brain stimulation in order to relieve severe depression.

Now we’re discovering drugs that modify our desires in new and ever-more-interesting ways. Researchers are finding that GLP-1 drugs like Ozempic, which suppress appetite and enable weight loss, actually modify human desires in a number of interesting ways:

The current breakthrough weight-loss drugs are only the beginning, according to Danish researchers hard at work on a new treatment that targets the brain's natural plasticity, which could offset bad side effects and provide more long-term benefits…

Where current GLP-1 drugs mimic the natural hormonal response following eating, signaling 'fullness' and slowing the emptying of the stomach, the new treatment instead uses GLP-1 peptide to "smuggle" molecules across the blood-brain barrier and into the appetite control center…[T]his new approach could harness the brain's plasticity to cement new pathways in its appetite center – pathways that would remain in place long after treatment had ceased.

And there are also signs that these drugs help remove the desire for alcohol and other addictive drugs. Imagine if addicts could recover just by taking a pill!

Drugs, meanwhile, are only the beginning of desire modification. If pharmaceuticals are a blunt instrument, neuromodulation — directly interfering with the brain’s electrical circuits — has the potential to be a delicate scalpel. Neuralink, the most famous new brain implant device, is already achieving interesting results, and it’s only one of a number of devices and approaches currently being tested.

Perhaps the ultimate technological achievement will be to hack human nature itself.

5. People are thinking constructively about deregulation

Deregulation, I always say, is too important to leave to the deregulators.

Well OK, I don’t really always say that, but I plan to start now. Basically, for decades we Americans had a bunch of laissez-faire types — neoliberals, free marketers, libertarians, whatever you want to call them — tell us that the only good regulation was a repealed regulation. What each regulation did, exactly, was of secondary interest — deregulators would measure regulation by the number of pages in the federal register, or other such bulk measures.

That approach wasn’t very helpful policy-wise, because essentially no politician wants to indiscriminately shrink the federal register. And when researchers started looking into the idea, they found that sheer volume of regulation was a very poor predictor of microeconomic outcomes.

So does that mean regulation is benign and we should leave it alone? Quite the contrary. It just means that “regulation” is an umbrella term that encompasses something far too general a category of policy to be simply good or simply bad. Instead, we need to dig into the specifics of regulations, in order to find out which ones help and which ones harm.

Fortunately, I see a lot of smart people doing exactly that these days. For example, here’s a Niskanen Center report on site-based billing for Medicare, arguing that this causes the government to overpay for health care services and exacerbates monopoly power in the health care space, while not improving health outcomes for patients.

A second example is Alexander Kaufman’s crusade to improve building codes. Rules about how buildings are built can have a huge impact on energy efficiency, but U.S. building codes are highly fragmented and out of date.

A third example is this Commerce Department report about how to improve permitting and other regulatory burdens for manufacturing. This is obviously very important if the U.S. is going to revive its industrial base. Commerce asked a ton of manufacturers and manufacturing-related companies to tell them what the most burdensome regulations were. They identified about twenty sets of rules that are the most burdensome; most of these were environmental rules, and many related to permitting. The next task is to review these rules and ask how to protect the environment while still being able to build lots of factories quickly and cheaply.

An article by Thomas Hochman in American Affairs supports this general idea, arguing that the Clean Air Act was written hastily and sloppily, and that a smart rewrite of the act would be able to protect air quality just as much while not blocking factories, power plants, or housing.

These are great efforts, and they are only a taste of what’s going on out there. There’s really a renaissance in thinking about how to improve regulation in the U.S. — not to slash it, but to reduce it where necessary, rationalize it where appropriate, and even add new regulations if need be. This is a really exciting area of intellectual ferment and a vast opportunity for wonkish policy analysis. It could also be crucial to the future of our nation.

Another fascinating "five things."

How concerned are you that industrial policy will fall prey to its usual predators––graft and inefficiency and special interests?

As for the working class, the book "Second Class" is an interesting read about the attitudes of the working class. I recommend it.

If America wants to create globally competitive manufacturing, it can't do it alone. German manufacturing would not have survived without outsourcing a bunch of their work to southern and eastern Europe. If you want America's supply chains to compete with Asia's you have to integrate central America and eventually the rest of Latin America into NAFTA.