At least five interesting things to start your week (#51)

Falling obesity; the red-state boom; U.S. housing supply; men avoiding college; China's economic goals; implicit taxes on the poor; Garcia interviews Krugman and Cowen interviews Scanlon

I haven’t done one of these roundups in a while, and I’m overdue! Once again, I’m going to steer clear of election-related stuff, since I’m writing so much about that in my regular posts.

I recently did a podcast with Brian Chau, one of the infamous young “Waterloo kids” from Canada, who now spends much of his time working to defeat AI regulation. He’s also a giant weeb. We had a very long and often goofy discussion about economics, AI, and Japan:

We’ve also got two episodes of Econ 102 with Erik Torenberg, on a variety of different topics, including international economics and the economic plans of the presidential candidates:

Anyway, on to this week’s list of interesting things!

1. Obesity is finally falling

“Acetaminophen/ You see the medicine/ Oh girl” — The White Stripes

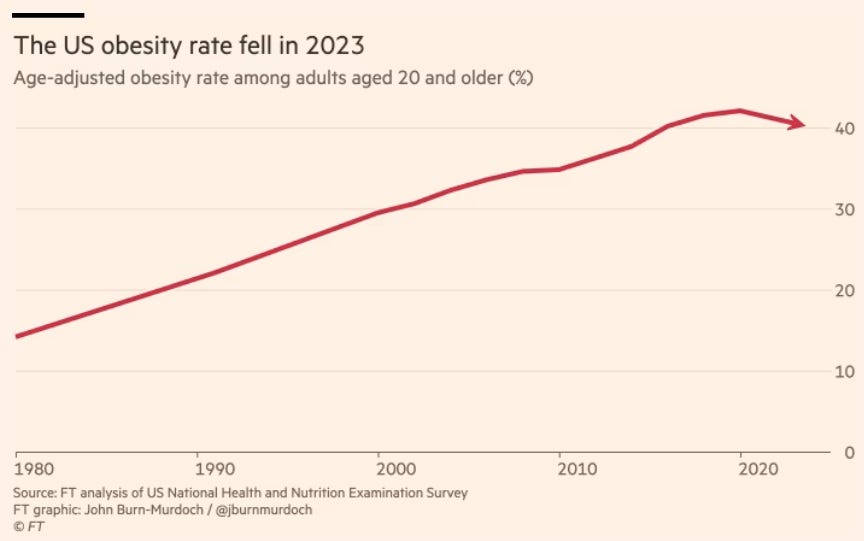

Here’s a big piece of good news. After rising relentlessly for decades, the obesity rate in America is finally falling. John Burn-Murdoch looked at the data from the U.S. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey — a very reliable data source that comes from doctors’ examinations — and found that obesity has fallen since 2020:

Note that there’s actually a problem with this chart (besides the fact that John still uses those misleading arrows at the end of time series). The actual NHANES data is collected over two-year periods. So the data that Burn-Murdoch labels as “2023” is actually data from August 2021 to August 2023. This slight mislabeling might lead us to make mistakes about the cause of the changing trend.

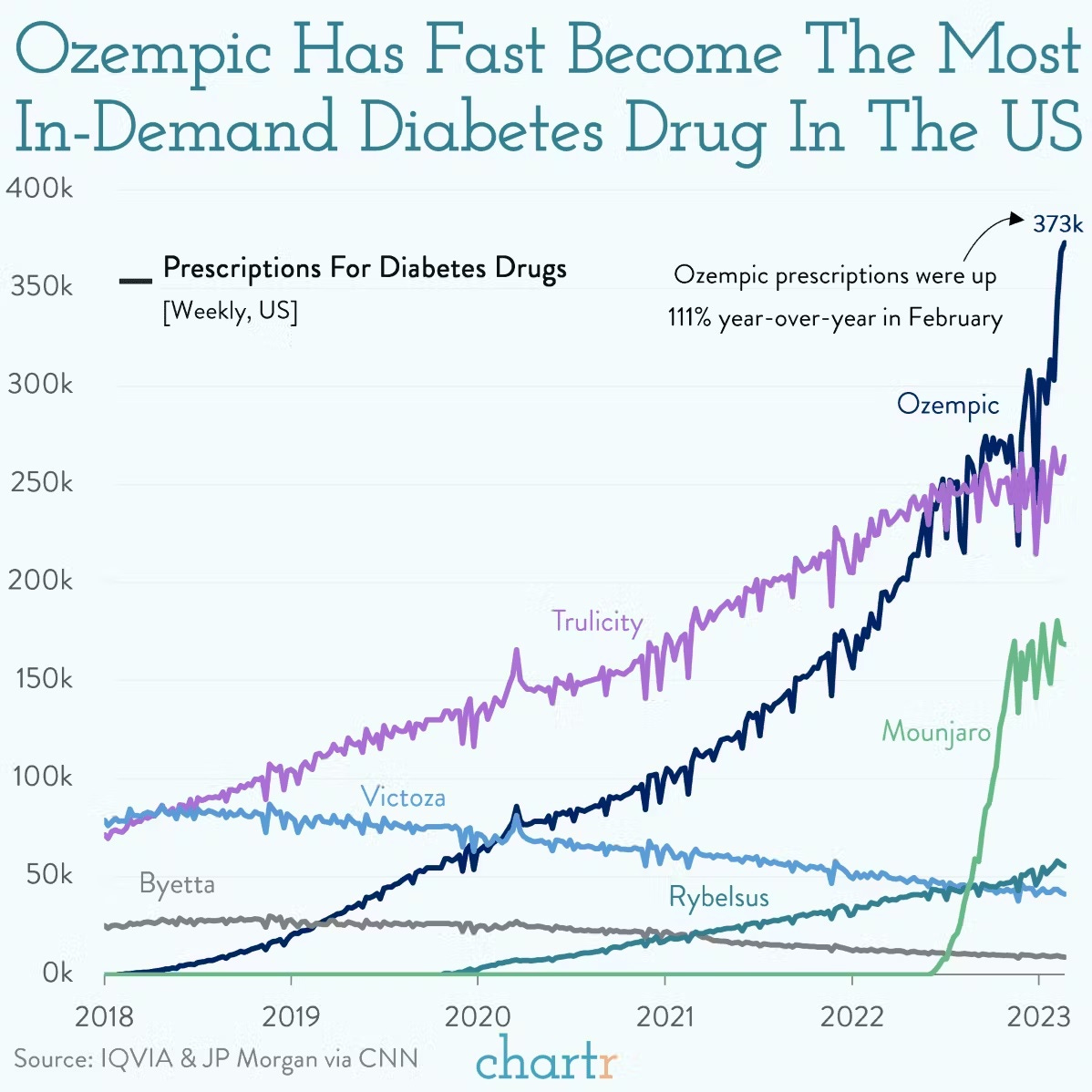

So what’s going on here? The obvious candidate explanation is Ozempic and other weight-loss drugs, whose use has soared in recent years. 13% of Americans have now used Ozempic. And although the drugs only became a media phenomenon since late 2022, their actual prescription — for diabetes, which is strongly correlated with obesity — has actually been rising since 2018:

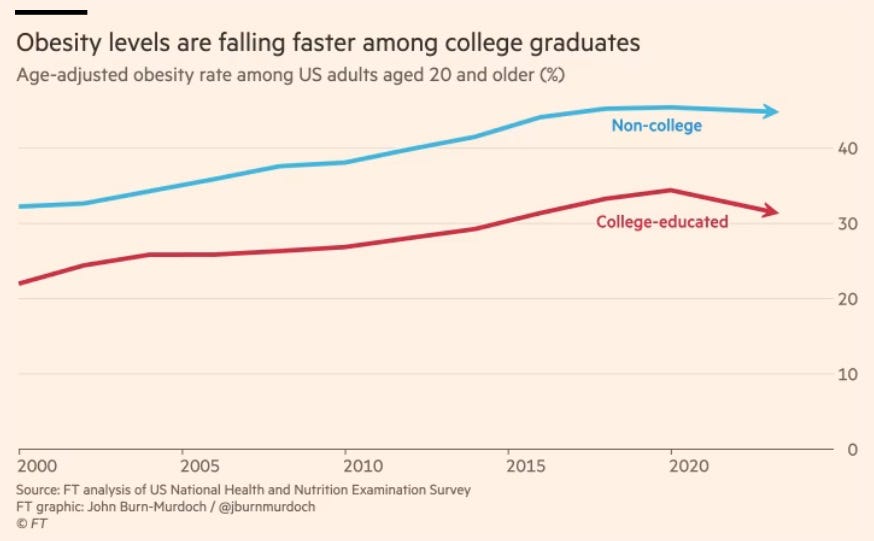

But Burn-Murdoch noted another interesting tidbit, which is that obesity rates for non-college Americans plateaued a few years before obesity for college-educated Americans started falling:

You have to figure that non-college Americans, on average, have worse medical care and lower knowledge of new drugs than college-educated Americans. So I see a possibility that the obesity decline is multi-causal — that there’s some kind of cultural or institutional force at work in addition to the miracle drugs.

In any case, though, I think the power of technology is clear here. I often half-jokingly call myself a “technological determinist”, because I tend to think that human culture adapts to the possibilities afforded by technology. In this case, the obvious story is that decades of cultural fat-shaming failed to stop the relentless rise in obesity, until a miracle drug came along and allowed us to treat it as a medical problem instead of a personal failing. As Scott Alexander once said, “society is fixed, biology is mutable.” Of course, the early plateau in non-college obesity leaves open the door for the possibility that culture was already moving on its own to stem the rise in obesity. So we don’t know for sure.

But anyway, I wonder what other personal problems we could reframe as technological challenges to be solved rather than personal failings to be shamed. How about addiction? Fortunately, there’s some evidence that Ozempic also helps with that! In fact, Ozempic might be the closest thing to a miracle drug that we’ve invented in recent memory:

Regardless of whether that level of optimism turns out to be justified, I think Ozempic’s effect on obesity should cause us to reevaluate how we think about our own biology and health. The human animal is a machine, and machines can be fixed.

2. The red-state boom

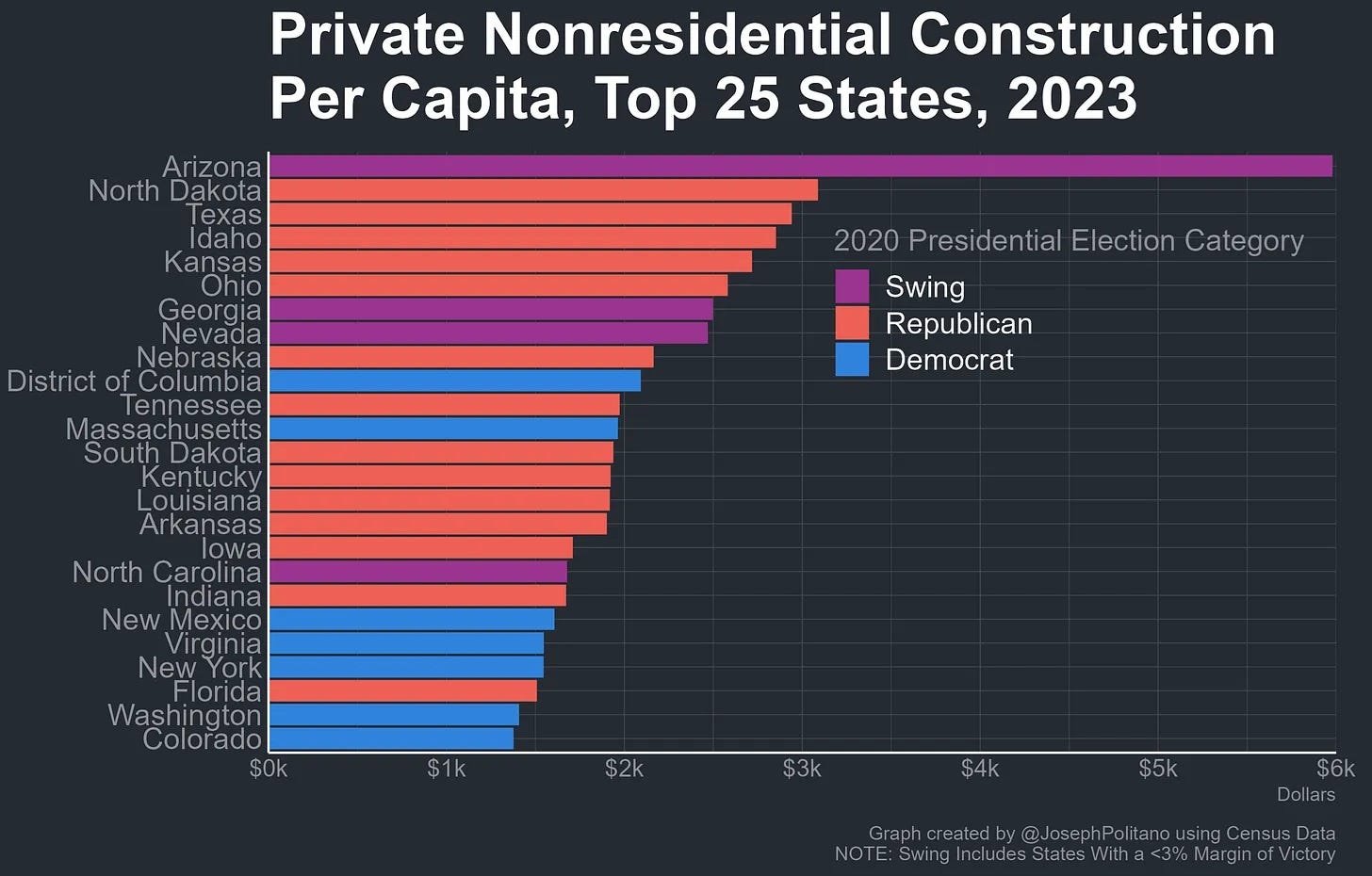

The Biden years have seen the return of industrial policy — the hand of the state is once more reaching down to guide the direction of national development. So it might be surprising that the lion’s share of the investment and jobs created during this era are going to states that voted against Biden!

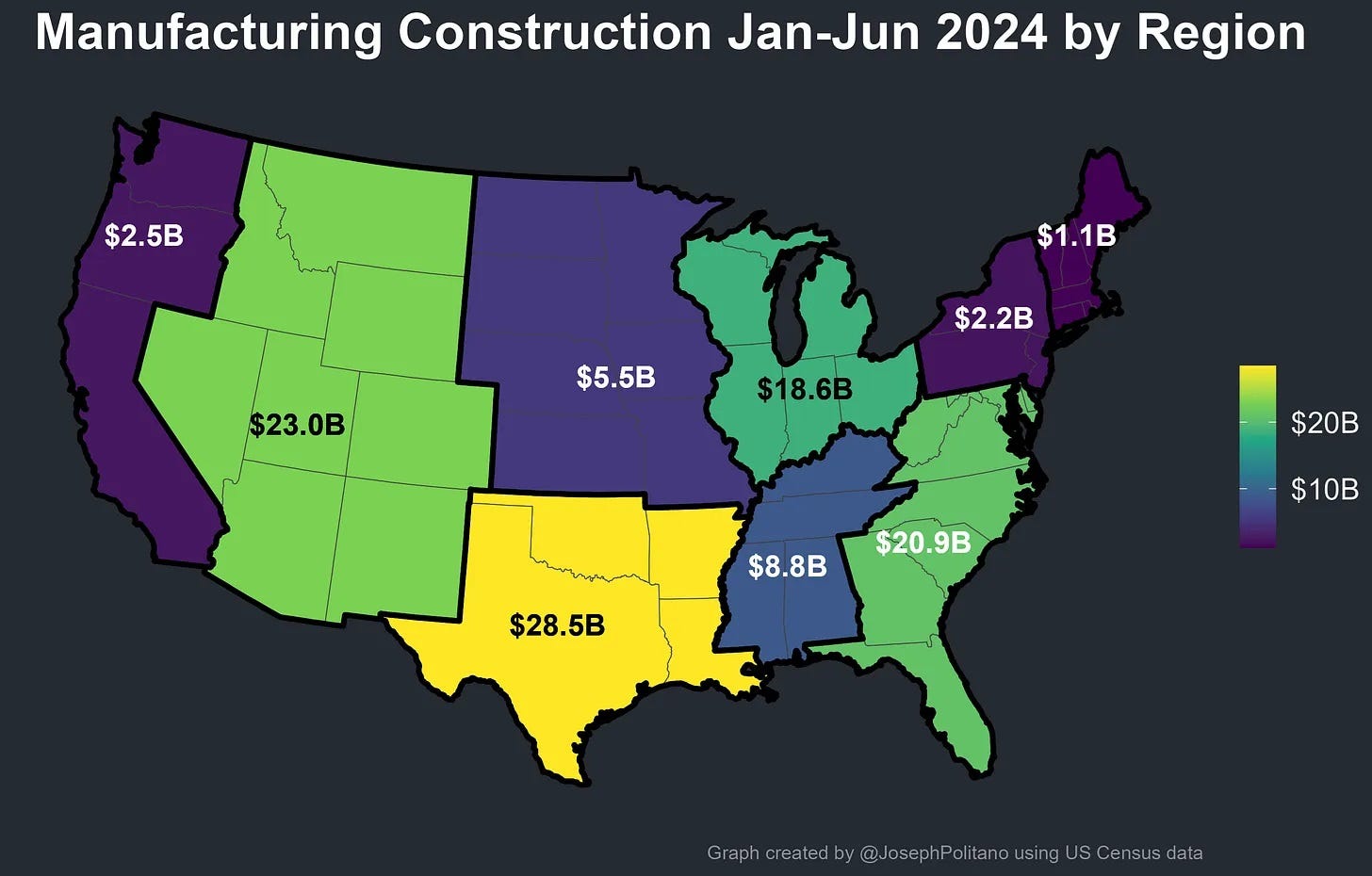

Joey Politano has a good breakdown of where the investment boom is happening, with lots of good maps and charts. Here’s a good chart:

And here’s a good map:

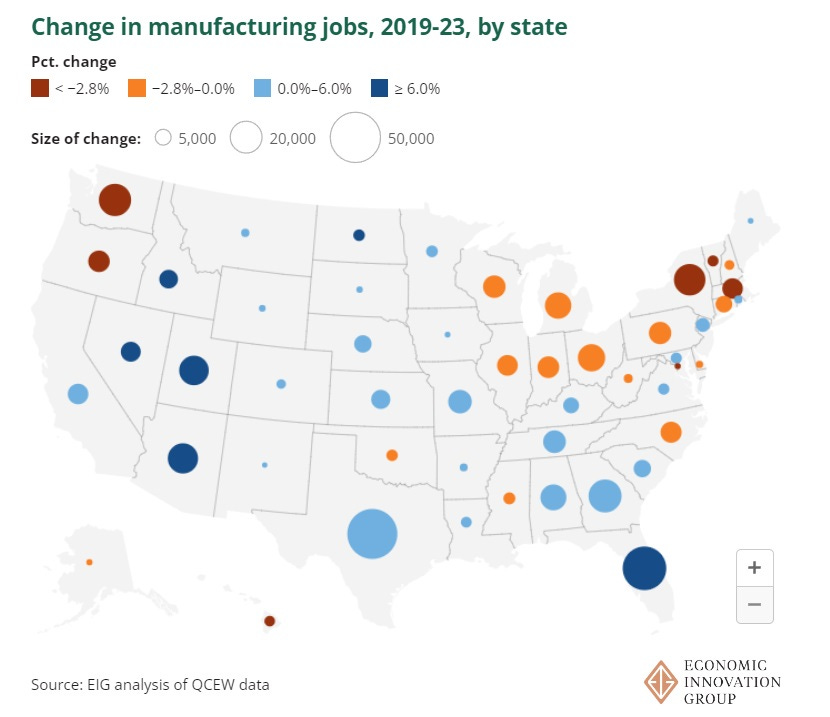

Meanwhile, the Economic Innovation Group’s August Benzow and Connor O’Brien have a good breakdown of where manufacturing jobs are growing in America. Again, it’s mostly concentrated in red states, especially the Southeast, Texas, and the Interior West:

One typical story you hear about this is that the Biden administration has directed investment toward red and purple states in order to win enduring bipartisan popularity for industrial policy. I think this is part of the explanation, and it might even work. But in fact, I think the more important story here is that red states just tend to be the places that allow companies to build stuff, while blue states and blue cities have a bunch of rules that prevent construction:

The Wall Street Journal wrote this back in February:

Industry experts say Republican-leaning states are luring companies with policies such as easier controls over land development and lower costs for labor, taxes or electricity.

I’ll write more about this later, but I think what we’re starting to see is that America’s new economic paradigm is going to be about federal guidance and subsidies paired with state and local deregulation and mostly private investment. This pairing doesn’t fit neatly into the standard “government vs. private-sector” debates, but it looks like it’s going to be what actually works.

3. YIMBY America?

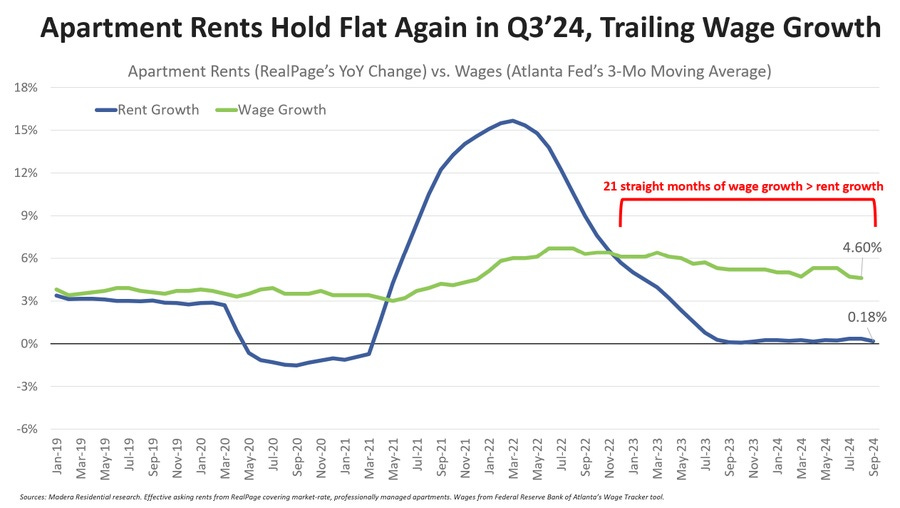

When we talk about YIMBY success stories in America — places where new housing supply held down rents — we usually talk about Minneapolis or Austin. But what about America itself? Housing economist Jay Parsons believes that a flood of new housing supply is holding down rents in America, even as demand for housing increases:

And here is his chart:

In fact, U.S. housing supply growth has recovered to the levels it enjoyed before the bust in 2008:

I’d like to trumpet this as a great YIMBY success, and I do think this new supply is helping put downward pressure on rents. That said, I think there are some other candidate explanations here.

For one thing, remote work is causing some Americans to move out of expensive cities and into cheaper cities, while earning roughly similar wages. If the housing supply curve is nonlinear — i.e., if the same worker bids up the price of a San Francisco unit more than the price of a unit in Nashville, TN — then this movement could be helping hold down rents. At the same time, remote work could be making people move to places that are willing to build more housing in order to accommodate newcomers, so this could dovetail with the “YIMBY America” story.

Another factor in slowing rent growth might be slowing household formation. The number of households in America has begun to plateau as population growth slows:

Finally, the homeownership rate has risen since 2017, as a big part of the large Millennial generation has made the transition from renting to owning:

This shift in demand is probably taking pressure off of rents and putting more pressure on house prices.

So anyway, I think there could be a lot of factors at work here, and it warrants more investigation. But I’m glad America is building more housing, and I’m sure that’s helping to keep rents down.

4. Today in “theories I don’t believe”

Celeste Davis has a very widely read post, in which she theorizes about why more women go to college than men:

Her theory is that men are avoiding college in order to avoid women:

Male flight describes a similar phenomenon when large numbers of females enter a profession, group, hobby or industry—the men leave. That industry is then devalued…

When mostly men went to college? Prestigious. Aspirational. Important.

Now that mostly women go to college? Unnecessary. De-valued. A bad choice.

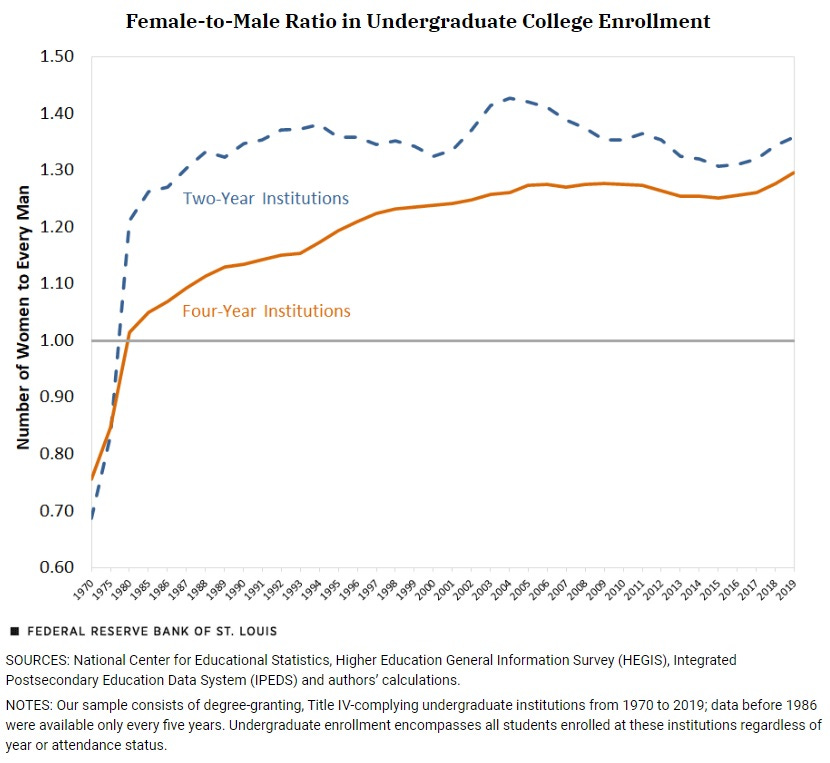

I’m incredibly skeptical of this theory, for two reasons. First, although there have been some recent small ups and downs, most of the shift to more women going to college actually happened long ago:

In fact, the big plunge in male college enrollment in the 1970s was probably just the end of the draft — men were hiding from the Vietnam War by going to school. Also, federal law changed in 1972 to outlaw gender discrimination in admissions.

Women have been more common at college for four decades. And yet for those four decades the gender ratio was stable, with no mass exodus of men. That immediately throws cold water on Celeste Davis’ theory that men run away from college once it becomes female-coded.

The other reason I’m highly skeptical of Davis’ theory is that if there’s one thing 18-year-old guys tend to want, it’s to be around girls. Young Americans may be having less sex these days, but I find it hard to believe that the basic motivations of young men have been reversed to that great a degree.

5. China’s economic goals

Arthur Kroeber is one of my favorite experts on the Chinese economy, and his book China’s Economy: What Everyone Needs to Know is a must-read (although now fairly dated). So I’m strongly inclined to listen to him when he tells us what China’s government wants for its economy:

Xi’s strategic aims have not changed. He wants to shift capital from the property sector into technology-intensive manufacturing, which he sees as the basis of China’s future prosperity and power. Long-term economic growth, he believes, is driven by investment in technology, which will eventually generate high-wage jobs and rising incomes. China’s core task is not to maximise GDP growth but to create a self-sufficient, technologically powerful economy immune to efforts by the US to stunt its rise.

This programme is cogent as a national strategy, but unfriendly to financial investors. The emphasis on investment means that supply will always run ahead of demand, leading to deflationary pressure, which is bad for corporate profits. Even the favoured high-tech sectors face intense competition that will erode margins…

In sum, the economy and financial returns are likely to pick up in the coming months. In the long run, though, China’s vision is unchanged: technology and self-sufficiency matter more than growth and profits.

This fits very closely with the mental model I’ve had of Xi Jinping since at least 2021. The basic model is this:

Xi’s overriding priority is to make China a geopolitically dominant and militarily strong nation.

Xi sees certain types of economic activity — especially advanced manufacturing and agriculture — as crucial for national power.

Xi sees other types of economic activity — real estate development, health care, internet software, finance, private education, etc. — as less useful for national power.

Thus, Xi will prioritize the growth of advanced manufacturing above all else. His attitude toward the other sectors will depend on whether he thinks, on balance, that they help build political support for his national greatness project, or whether he thinks they divert resources from that project.

The pivot toward stimulus in recent weeks can be interpreted as a shift in Xi’s thinking. In 2021-23 he thought that diverting resources from real estate, IT, and services was crucial for boosting advanced manufacturing. But now, with a demand shortage hurting the country’s economy, and many Chinese people becoming disaffected, he has probably concluded that the political risks of letting large parts of the economy languish are too high. Thus, stimulus is being increased.

6. Implicit taxes are real and important

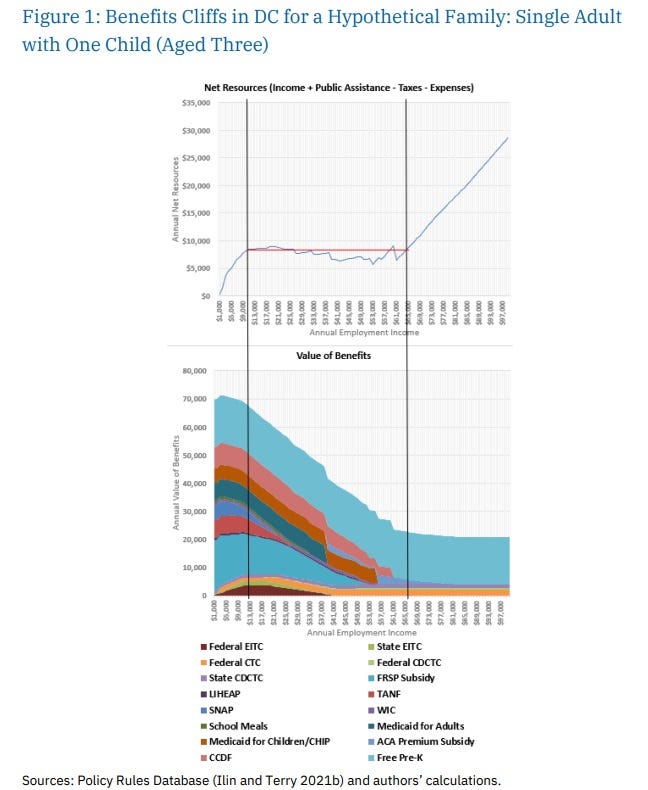

Usually, we think of taxes as “the government takes your money”. And the more you make, the more government takes, even with a “flat tax”. But sometimes, what happens is that the government gives you less money as you earn more of it yourself. This is also a kind of tax, even though it doesn’t get counted in the official tax rate or official tax revenue. This is an example of what economists call an “implicit tax”. But in terms of its effect on people’s pocketbooks, it’s just as real as the explicit kind.

The U.S. has a stronger welfare state than most people realize, but it’s also heavily means-tested. If you make more money, you lose your benefits. This can be very frustrating for poor people, since it means they just can’t seem to get ahead no matter how hard they try. For example, Ilin and Sanchez (2023) model the situation of a single parent living in Washington, D.C. with a single three-year-old. They find that once this person hits $13,000 of earned income, they can’t get any more “net resources” — defined as total income minus a set of basic life expenses — until they earn more than $61,000:

This is kind of insane and dystopian. Imagine making $13,000 a year as a part-time checkout clerk, and then busting your butt for years to make it into the middle class as a medical worker making $61,000. And then imagine having an actual take-home income that’s exactly the same as you started out with, because as you make more and more, the government takes away your benefits!

With incentives like that, why even try in life?

Anyway, the obvious solution to this is to make benefits phase out more slowly, so that the implicit tax rate is lower. There are various ways to do that — less means-testing, more unconditional benefits, and so on. But they all cost a lot of money, and they can make the tax system look less “progressive” on paper. So this is a very tough problem. At the very least, governments should eliminate “benefit cliffs” where benefits disappear abruptly at some income threshold.

7. Two great interviews

I’d like to direct your attention to two very excellent interviews, featuring four of my favorite people in the economics blogosphere. One features an econ pundit interviewing an economist, and the other features an economist interviewing an econ pundit.

In one interview, the excellent Cardiff Garcia interviews the excellent Paul Krugman. Here’s Krugman being pessimistic about the possibility of boosting the trend rate of economic growth by a large amount:

[I]f you look at a chart of U.S. potential GDP growth over the past 50 years — we had some pretty big political swings in there, big changes in tax policy. If you didn't know that there have been changes of administration, changes in tax policy, you would never guess. It's pretty much just a flat line. The reason is that economic growth is largely driven by the Solow Residual. And who knows how to make that change very much…[U]ltimately, talking about innovations, there's a big mystery now. It feels like we've had a lot of technological change these past 16, 17 years, and yet, if we believe our numbers, which maybe we shouldn't, but if we believe our numbers, total factor productivity growth has been really pretty lousy for that whole period.

And here is Krugman on tariffs and China:

If we're getting a lot of our toys and footwear from China, I don't think that creates any particular strategic vulnerability…But I do think it makes sense, given geopolitics, to be pretty serious about advanced technology, to a certain extent industrial capacity. I think one of the really scary things that we've learned is that the age of large scale conventional wars where your ability to churn out weapons actually matters has not passed…

[T]rying to make deals, friendshoring one way or another, makes sense — I think TPP was probably too broad and got too much baggage associated with it.

And here is Krugman on place-based policy:

The history of place-based policies is not great. I mean, the Germans have spent vast sums trying to make East Germany hold on, and it basically hasn't worked. The Italians have spent enormous sums on the Mezzogiorno…But it's not total failure. You get particular—well, Springfield, Ohio is an example of, in a way, how a place can be revived. That's not actually a result of—that revival predates the Inflation Reduction Act. But it is the kind of thing that you can do. So you can produce at least some surviving, thriving centers in the hinterlands—the places that are not the core.

And here is Krugman on NIMBYism:

New York, the refusal to build housing, that is definitely a Democrats problem…The NIMBYism, though, if you ask why has Texas overtaken New York, the biggest single reason is that somehow they just don't have much zoning. And so, they can build housing.

I strongly recommend the whole interview.

In the second interview, the great Tyler Cowen interviews the great Kyla Scanlon. Here is Scanlon on the inevitable negative attention that comes with the territory of being an economics communicator:

[A] lot of the comments are personal. They see you as a nonobjective commentator, even if you’re talking about data. For me, it’s been difficult the past few months because you’re talking about various data sources, what’s going on with inflation, what’s going on with the labor market. But because we’re in a post-truth society, everybody is like, “You’re lying.” “You’re a liar.” “You’re horrible for that.” I’ve worked on that because you’re just a figment of the audience’s imagination.

And here is Scanlon on the low quality of the economics ideas that people are now learning on TikTok:

I would say it’s definitely conspiratorial. There’s a lot of desire to pin inflation onto companies, which I don’t know if that’s the best thing to do. There’s a lot of desire to have a scapegoat. I think a lot of people are frustrated with their economic situation, and so they look at TikTok videos, and somebody is telling them that, yes, Blackrock is conspiring against them, and that’s very soothing. I think that’s where we have ended up with TikTok and econ.

And here is Scanlon on the changes in the short video market:

People aren’t on there as much. I think Instagram Reels has surpassed it in popularity. Mark Zuckerberg just continues his domination path. I think, also, the algorithm is maybe not as good as it used to be. Perhaps it’s because not as many people are scrolling, but there’s more and more focus on TikTok Shop.

TikTok really wants to make a lot of money, and they’re like, “If we sell commerce, if we sell goods to people, that’ll be the way that we make money.” Now, every other video for people is a face mask or a purse or clothes. You have users that are constantly being advertised to. I think more people view TikTok as an exhausting experience than one of connection, as it was in 2020…

Reels is a little bit different because they have curated it to be more wholesome. You’re not constantly being advertised to, at least not as directly and as gimmicky as TikTok. I think that there’s more focus on the authentic creator.

What’s nice about Instagram as a platform is that you have stories and that you have posts and you have reels, versus TikTok does have stories, but when you scroll on TikTok, you don’t really scroll for a single person. Instagram — you’re able to curate more of a personality because there’s a profile page. It’s not as algorithmic. There’s more intentionality, I think, with the platform design, versus TikTok just wants to keep you scrolling and scrolling and scrolling. I think Instagram — it seems to be okay if you stray from the path awhile.

And here’s Scanlon on negativity bias in the media:

We were just talking about negativity in media, and there’s a chart that I like that shows the sentiment in media. Headlines have gotten extraordinarily negative. Everything has a story. It’s a business model.

Anyway, once again I strongly recommend the entire interview, which is very long and wide-ranging, and has lots of interesting thoughts and input from Tyler as well.

The thing you didn't mention that makes me even more skeptical of the men avoiding women point: men do worse in education at EVERY level. k-10 education has been compulsory for most living Americans lifetimes, yet even when it's genuinely not possible for men to avoid spaces with women in them they still do worse. Lower grades, lower attendance, lower test scores, more disciplinary issues, higher failure and drop-out rates. It's not like men are killing it educationally and then deciding that girls are icky and becoming plumbers.

I honestly find it a bit cruel how dismissive some people are about the failure of men in education relative to women. There's a kind of weird irony to it as well, with progressives at times basically telling men to "pull themselves up by their bootstraps" and fix their own problems.

Alongside Ozempic, Covid might also play a role in falling obesity rates after 2020. The correlation between obesity and Covid mortality was widely publicized, and millions of Americans know someone who died. Perhaps a growing proportion of Americans started taking their own weight issues more seriously in the fallout of the pandemic. Obvious counterargument would be no one took the other other health risks of obesity seriously before, but the sweep of Covid through the country was a far more visceral experience for many.