At least five interesting things: No, You're Wrong edition (#70)

Doomerism; Stereotypes about Indians; Nobel laureate age; AI and radiologists; Europe vs. China

Hi, folks! I haven’t done one of these roundups lately, so I’m overdue!

Econ 102 is moving to one episode every two weeks, since Erik is very busy starting his new job at a16z. But never fear, I have some other projects in the works, for those of you who enjoy hearing my voice. In the meantime, here’s one Econ 102 episode, which itself was delayed due to legal issues switching the podcast over to a16z.

Anyway, on to this week’s list of interesting things, which is mainly just me telling people they’re wrong about stuff.

1. Doomerism is so passé

I don’t see nearly as many pessimistic screeds these days as I did a couple of years ago. But every once in a while, one pops up on my screen, and it’s invariably just as maudlin and overwrought as they all are. The latest example is an essay in the New York Times by Andreas Reckwitz from Berlin, entitled “The West is Lost”.

Why is the West lost? Well, fairly predictably, he starts out with climate change:

The most dramatic loss is environmental. Rising temperatures, extreme weather, disappearing habitats and the ruination of entire regions are eroding the conditions of life for humans and nonhumans alike. Even more threatening than present damage is the anticipation of future devastation — what has aptly been termed climate grief. What’s more, mitigation strategies themselves promise losses: a departure from the consumer-oriented lifestyle of the 20th century, once celebrated as the hallmark of modern progress.

Look, climate change is obviously a bad thing, but let’s not exaggerate. The notion that runaway climate change was going to make the Earth uninhabitable was always highly dubious; in 2021, the author of The Uninhabitable Earth wrote an article entitled “After Climate Alarmism”, in which he embraces more balanced, reasonable forecasts. Thanks to the amazing progress in renewable technology, and China’s gung-ho willingness to scale that technology rapidly, the world will probably be spared the worst. And the idea that climate change is going to be solved — or even meaningfully altered — by pious Europeans eschewing modern consumer lifestyles is just numerically illiterate. Technology is solving the problem while German intellectuals wring their hands.

Next up, Reckwitz tells us that we’re experiencing economic devastation:

Economic changes have also brought loss. Entire regions once defined by prosperity — Rust Belt America, the coal fields of northern England, small-town France, eastern Germany — are now locked in decline. The optimism of the mid-20th century, when upward mobility seemed the natural way of things, has proved exceptional rather than typical. It was, it turns out, a historical interlude. Deindustrialization and global competition have fractured societies into winners and losers, with large segments of the middle class seeing their security erode.

I wrote a whole post debunking the notion that globalization hollowed out the American middle class:

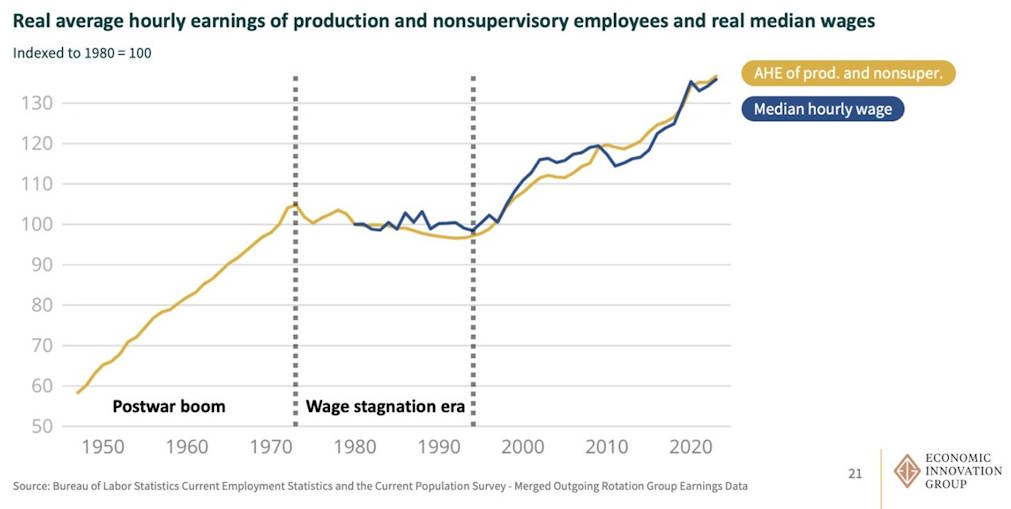

In fact, middle-class wages have risen almost as strongly in the “neoliberal” era as they did in the glorious three decades after WW2:

Reckwitz also claims that infrastructure is deteriorating in the U.S. No it isn’t. The American Society of Civil Engineers has upgraded the country’s infrastructure “report card” in recent years. Yes, American infrastructure costs way too much, but the government ponied up the cash.

Now, there are some major problems the West (defined here as America, the Anglosphere, and Europe) has yet to really address. These include low fertility, low trust in government, and housing shortages. America’s politics are certainly not encouraging. But every civilization, at every time in its history, faced major problems. With the possible exception of low fertility — which no one knows how to reverse — all our problems are eminently solvable.

I think many American progressives take it as almost an article of faith that if we exaggerate the severity of our problems, it’ll galvanize society to greater action. But op-eds like this one demonstrate that such pessimistic exaggeration simply paralyzes people into hand-wringing helplessness.

2. Indian entrepreneurs aren’t very clannish

In 2025, I’ve started to hear a lot more anti-Indian sentiment, including in some fairly elite tech circles. I talked about it in a post last month:

And as for self-dealing and ethnic exclusivity, I’m starting to hear this charge thrown around a lot as well, on social media and even in some San Francisco parties.4 The X user “Power Bottom Dad”, a harsh critic of H-1bs, has identified at least two lawsuits in which a big American company was accused of preferentially hiring Indians or discriminating against U.S. citizens. Whether that is a general pattern, as Power Bottom Dad asserts, or a couple of isolated incidents that could be found from time to time among any ethnic group in America, is probably irrelevant to the politics of the issue; what matters is that there is a portion of Americans out there who see Asian immigrants, and particularly Indian immigrants, as a clannish self-dealing cartel.

Well, I recently discovered that the economists Sari Kerr and William Kerr actually wrote a paper in 2021 that challenges some of those stereotypes. Here’s their abstract:

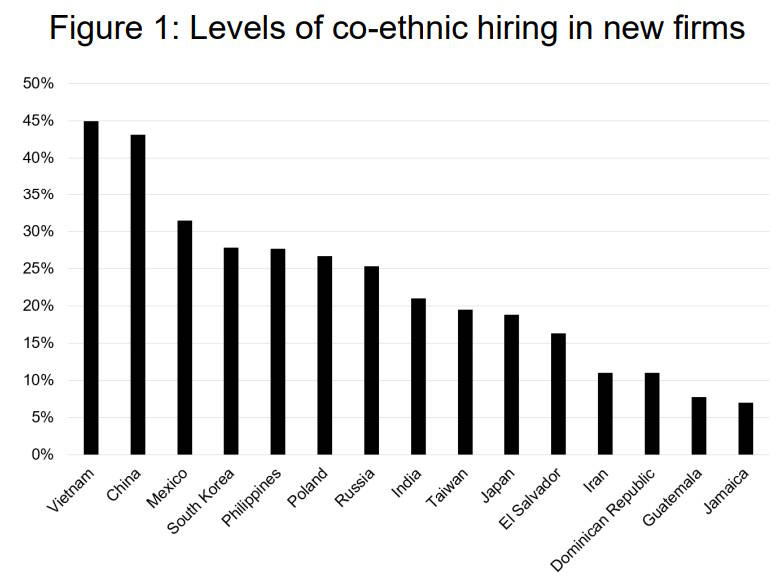

We explore co-ethnic hiring among new ventures using U.S. administrative data. Coethnic hiring is ubiquitous among immigrant groups, averaging about 22.5% and ranging from <2% to >40%. Co-ethnic hiring grows with the size of the local ethnic workforce, greater linguistic distance to English, lower cultural/genetic similarity to U.S. natives, and in harsher policy environments for immigrants. Co-ethnic hiring is remarkably persistent for ventures and for individuals. Co-ethnic hiring is associated with greater venture survival and growth when thick local ethnic employment surrounds the business. Our results are consistent with a blend of hiring due to information advantages within ethnic groups with some taste-based hiring.

So clannishness among immigrant groups is common — which is not surprising, given that people tend to hire out of their personal networks, and immigrants know a lot of other immigrants. But as immigrants go, Indians are below average:

Why only look at new firms? Because A) it’s a lot harder to know who’s responsible for hiring in bigger, older firms, and B) since there’s a lot more discretion in hiring at startups and small businesses than at big companies, you’d expect new firms to show much more pronounced clannishness.

So why are Indians less clannish than Poles, Koreans, etc.? Probably because they usually speak at least pretty good English when they come over. As Kerr and Kerr note, the better that immigrants can speak English, the more easily they can form bonds of trust and cooperation outside of their ethnic community.

Anyway, I don’t expect this research to move the needle for the people who have already convinced themselves that Indians are especially clannish in the workplace. But for everyone else, I hope it adds some much-needed balance and perspective. And I hope it reveals that the impulse to blame social ills on Indians shows every sign of being a classic panic rather than a sober assessment of the effects of immigration.

3. Why are Nobel laureates getting older?

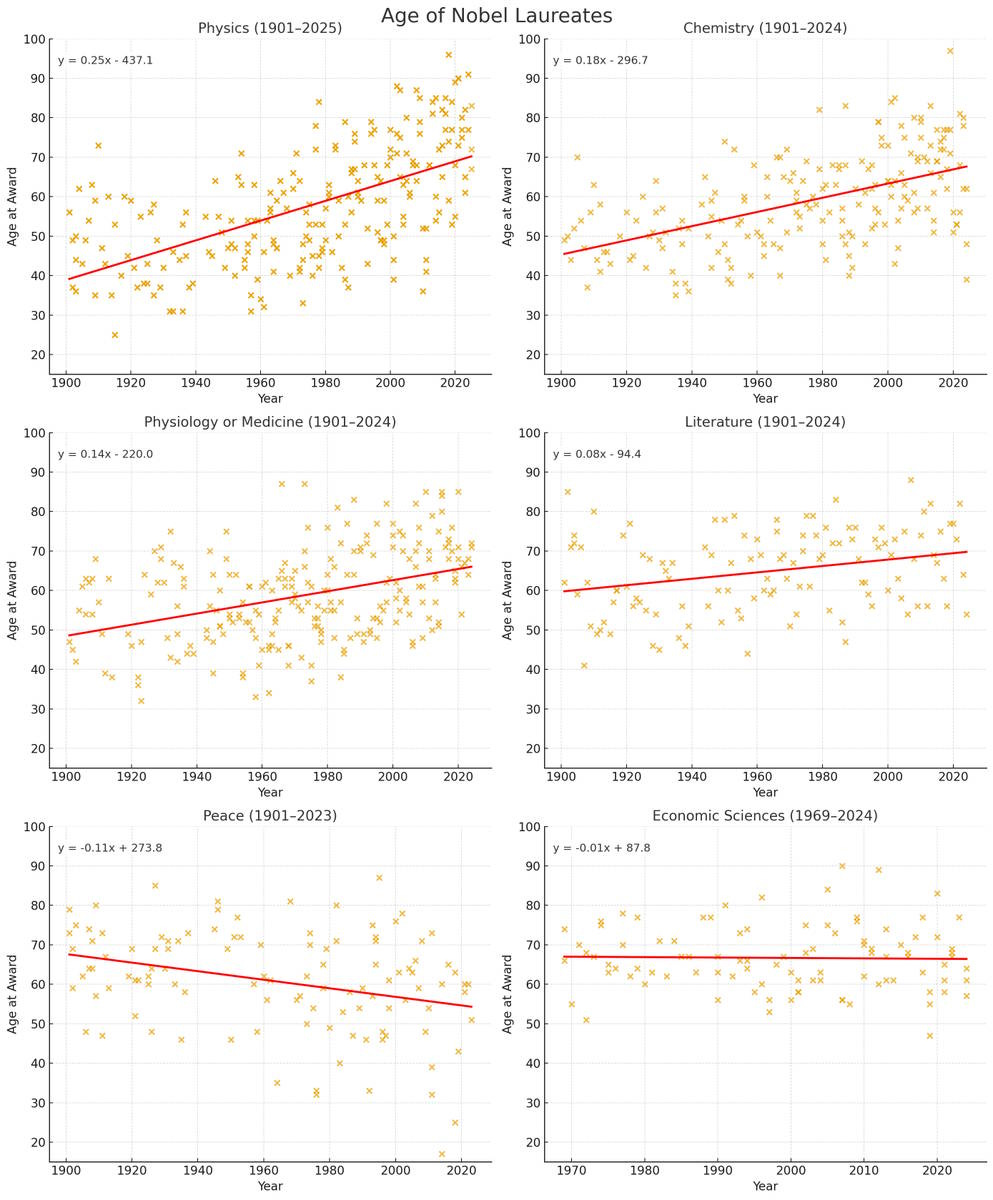

We just had the Nobel Prize announcements, and some people have noticed that in physics, chemistry, and medicine, the laureates seem to be getting older and older over time:

What conclusions should we draw from this trend? One possible interpretation is that recent discoveries haven’t been very groundbreaking, so a lot of the most important scientists did their work decades ago. People have tried to investigate this idea, and the evidence is generally pretty split.

But you can also make the exact opposite interpretation! Perhaps groundbreaking discoveries are actually becoming more common, so that there’s a large “queue” of scientists waiting for their prizes. The Nobel can’t be given posthumously, so older candidates naturally go to the front of the queue, so that they can get their prizes before they die.

Now here’s a subtle idea. A “queue” could also form if there’s a compression in the upper tail of the distribution of scientific discoveries. Suppose that these days, modern science is making more discoveries that are a 9/10 in terms of importance, but fewer 10s and 8s and 7s. That could improve the overall pace of scientific progress, while making the prize-winners seem less stand-out and special.

There are also neutral interpretations, like the “burden of knowledge” idea — the idea that as scientific knowledge accumulates over the decades and centuries, it takes more and more time to get up to speed on cutting-edge ideas. Maybe scientists are making just as many big breakthroughs as before, but now they’re forced to wait until they’re older in order to make them.

So really, we don’t know what’s behind this trend, or whether it’s good or bad.

4. Why do we still have so many radiologists in the age of AI?

A whole lot of people think that AI is going to eliminate many human jobs. Perhaps no one is more confident of this prediction than the engineers who are actually building the AI in question. For example, nine years ago, Geoffrey Hinton — one of the key creators of modern AI — declared we should stop training radiologists, because in five to ten years, they would be replaced:

“I think if you work as a radiologist, you are like the coyote that’s already over the edge of the cliff but hasn’t yet looked down…People should stop training radiologists now. It’s just completely obvious within five years deep learning is going to do better than radiologists…It might be 10 years, but we’ve got plenty of radiologists already.”

ChatGPT hadn’t yet been invented, but the AI systems of 2016 were already pretty good at reading medical imaging. Hinton felt that he could see the writing on the wall.

And yet here we are, nine years later, and the radiology profession is doing just fine. Deena Mousa recently wrote about this in an excellent Works in Progress article:

Radiology is a field optimized for human replacement, where digital inputs, pattern recognition tasks, and clear benchmarks predominate…But demand for human labor is higher than ever. In 2025, American diagnostic radiology residency programs offered a record 1,208 positions across all radiology specialties, a four percent increase from 2024, and the field’s vacancy rates are at all-time highs. In 2025, radiology was the second-highest-paid medical specialty in the country, with an average income of $520,000, over 48 percent higher than the average salary in 2015.

As Mousa notes, some of the reasons for this are pedestrian. AI models don’t perform nearly as well once they get out in the real world and have to go far beyond their training data. And humans don’t trust the AI, so regulators and health insurers sometimes insist on human radiologists.

But there are other reasons for the persistence of the radiology profession that are even more profound — and that should serve as important reminders about how little we know about the economic effect of AI.

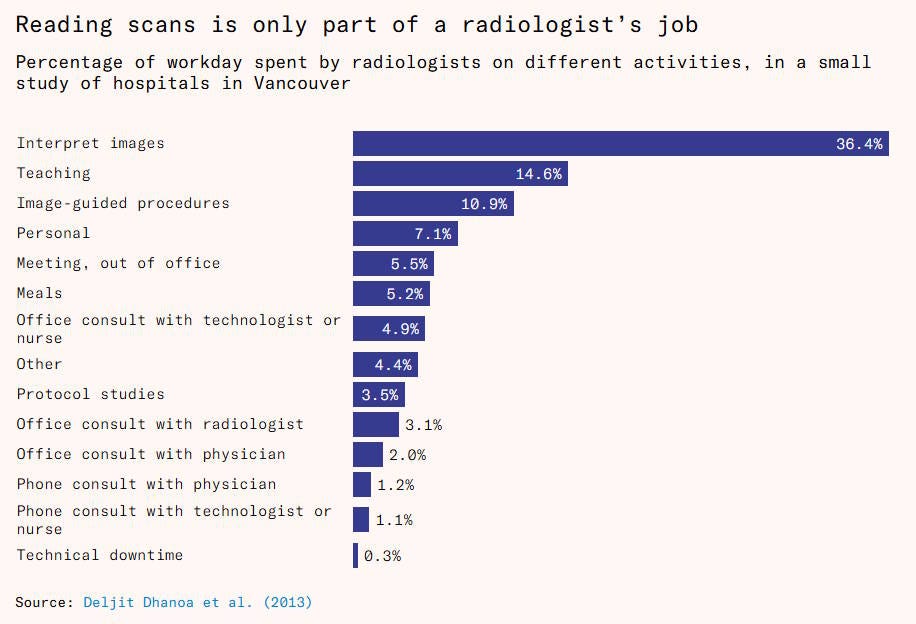

First, AI model makers don’t actually know what radiologists do. They know radiologists read scans, but they don’t know all the other stuff they do:

Radiologists are useful for more than reading scans; a study that followed staff radiologists in three different hospitals in 2012 found that only 36 percent of their time was dedicated to direct image interpretation. More time is spent on overseeing imaging examinations, communicating results and recommendations to the treating clinicians and occasionally directly to patients, teaching radiology residents and technologists who conduct the scans, and reviewing imaging orders and changing scanning protocols. This means that, if AI were to get better at interpreting scans, radiologists may simply shift their time toward other tasks. This would reduce the substitution effect of AI.

Because AI engineers don’t really understand all the things radiologists do, they will be slow to design AI systems that address all of these tasks. And even when someone does get around to addressing this problem, it’s not clear when we’ll get AI that’s as good at humans at all of these tasks. Humans may remain in the loop.

Finally, AI increases productivity, which reduces cost, which increases the number of patients who can be served. This increases the demand for radiologists’ labor:

As tasks get faster or cheaper to perform, we may also do more of them. In some cases, especially if lower costs or faster turnaround times open the door to new uses, the increase in demand can outweigh the increase in efficiency, a phenomenon known as Jevons paradox. This has historical precedent in the field: in the early 2000s hospitals swapped film jackets for digital systems. Hospitals that digitized improved radiologist productivity, and time to read an individual scan went down. A study at Vancouver General found that the switch boosted radiologist productivity 27 percent for plain radiography and 98 percent for CT within a year of going filmless. This occurred alongside other advancements in imaging technology that made scans faster to execute. Yet, no radiologists were laid off.

Instead, the overall American utilization rate per 1,000 insured patients for all imaging increased by 60 percent from 2000 to 2008. This is not explained by a commensurate increase in physician visits. Instead, each visit was associated with more imaging on average.

AI engineers, who look mainly at their models’ capabilities, don’t generally think a lot about this overall economic ecosystem. They’ve seen their creations up close, and they know their capabilities better than anyone else, but that doesn’t mean they know what a radiologist does at work. And they don’t know whether AI will simply change how radiologists spend their time at work while also improving their productivity. Hinton might some day be right, but as of right now he was wrong.

5. Is Europe starting to stand up to China, just a little bit?

For a long time, Europe has basically ignored every threat that came out of China. It has ignored the increasing evidence that China is supporting Russia’s war effort in Ukraine, which means that China is waging proxy war against Europe itself. And it has taken only modest measures against the flood of Chinese government-subsidized imports that threatens to deindustrialize and hollow out Europe’s manufacturing industries.

But while Europe is still in too parlous and precarious a state to do much about China’s military threat, it’s at least starting to push back on China’s cutthroat economic competition. For example, some Chinese companies have been trying to get around Europe’s tariffs by building factories in Europe. But Europe is unsatisfied with the prospect of having its people simply work for Chinese bosses; instead, the EU is now insisting that Chinese investments transfer technology to local European companies:

The European Union is poised to toughen its trade stance towards China, with the bloc set to insist that Chinese investors in Europe transfer technology to local firms…Trade chief Maros Sefcovic insisted on Tuesday that the bloc was open to investments from China but only under the right conditions.

These conditions include the creation of “real value added” in the EU, the creation of “real jobs”, and that there “will be real technology and real intellectual property “transferred, as European companies [have] been doing when they’ve been investing in China”…

It remains to be seen how such a policy would work in reality.

It’s not much, but it’s a start. Tech transfer requirements would allow Europe to build a globally competitive EV industry a lot sooner.

Of course if China retains control of those factories, it could still pose a threat if hostilities between the two blocks increases further. But European countries can just nationalize their factories at any time. In fact, the Netherlands just took over a Chinese semiconductor company:

The Dutch government has taken control of Chinese-owned semiconductor maker Nexperia, warning of risks to Europe’s economic security…The Dutch ministry said it invoked the country’s Goods Availability Act because of “recent and acute serious governance shortcomings and actions” at Nexperia, which is based in the Netherlands and has been majority-owned by Chinese technology group Wingtech since 2019.

I’m glad to see Europe discovering that it still has at least the vestiges of a spine. It’ll need a lot more than this in the years to come.

Editorial note: Netherlands not Denmark (Dutch not Dane)

'every civilization, at every time in its history, faced major problems'. The rarest of things - an online historical perspective on our current problems.

This should be inscribed above the door of every school, university and government building in the West, to stop people thinking they're walking into a doomed institution.