At least five interesting things for the middle of your week (#6)

My new podcast, China's chip struggles, where Americans are moving, strategies for growing exports, urban design, the IRA's effects, and Larry Summers' predictions

Exciting news, folks! For those who want to hear me talk — or even watch me talk — I’ve got something just for you! I’m doing a new podcast with the famed podcaster and entrepreneur Erik Torenberg. It’s called Econ 102, because A) we talk about econ-related things, and hopefully go a little beyond 101, and B) by a curious coincidence, I was a teaching assistant for Erik’s Econ 102 class at the University of Michigan. (The professor for that class was Miles Kimball, my PhD advisor, in case you’re wondering, Erik got a good grade). Erik is also a partner at Village Global, as well as a co-founder of Product Hunt and On Deck, and has hosted many podcasts in the past. Econ 102 is part of a new family of podcasts Erik is launching, called Turpentine.

Anyway, so Econ 102 is basically just Erik interviewing me about things I’ve written in recent weeks, and then us riffing on it — a bit like what Ben Thompson and Andrew Sharp do with their podcast Sharp Tech, but for econ stuff. You can listen to the first episode here on Spotify:

Or if you prefer Apple Podcasts, you can listen to it there. Or if you’d prefer to watch the video version, you can watch it on YouTube. If you’d like to subscribe to the podcast (which is free, though we plan on getting sponsors if people like the podcast), here’s a link where you can do that. And here’s a blog post that Erik wrote about our new show, in which he also thinks insightful thoughts about the immigration issue.

Anyway, Econ 102 is still in its infancy, so let me or Erik know any suggestions or feedback, via comments or email!

Of course, this doesn’t mean I’m canceling my previous podcast, Hexapodia, with the excellent Brad DeLong. Brad had to take a longish hiatus because he has a real job, but we’re back, and will try to post episodes every 2 weeks or so. In the latest episode, we talk about Daron Acemoglu’s idea that technological innovation can be steered or guided in advance in order to benefit workers — something I plan on writing a lot about in the weeks to come.

Anyway, here are your Five Interesting Things for this week. Which are actually Six Interesting Things, since I pulled an extra one from last week’s comments. As always, if you’re a paid subscriber, feel free to leave links in the comments if you’d like me to take a look!

1. Chip export controls are hitting China hard so far

This week I posted my interview with Chris Miller in which we discussed the U.S.’ semiconductor export controls on China. It’s always important to get some confirmation of whether controls like this are working. Fortunately, Joey Politano has an excellent deep dive on what we know about China’s chip industry in the wake of the controls.

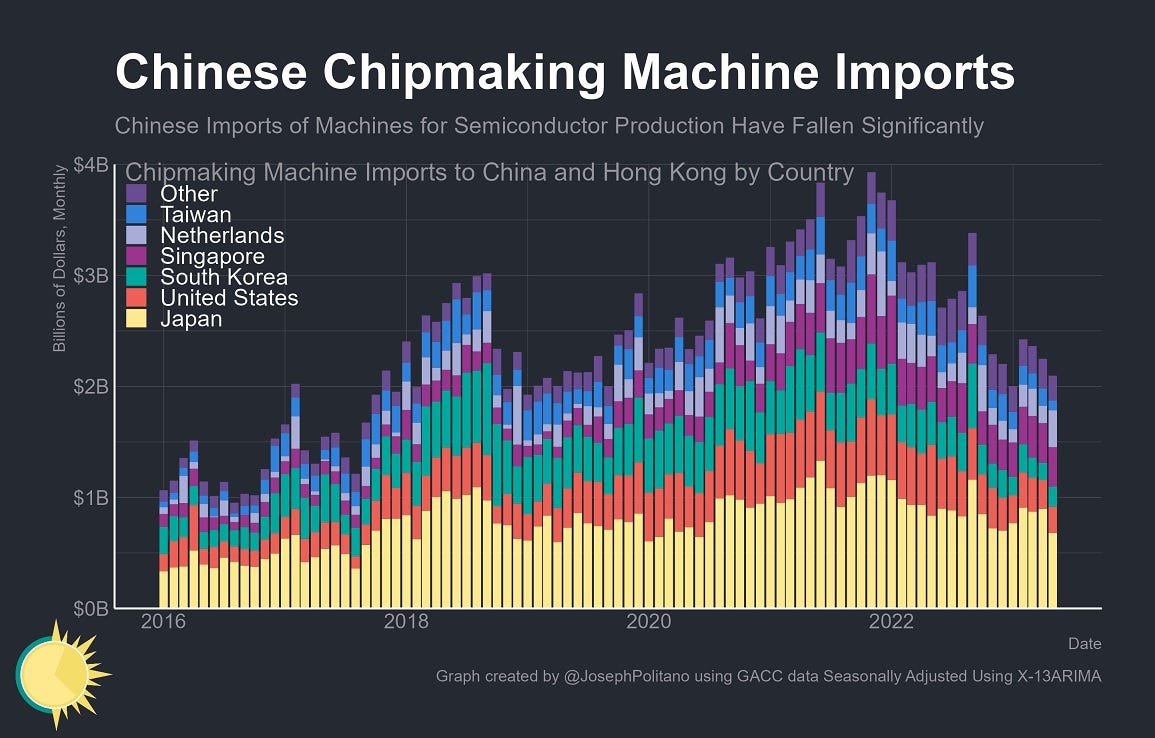

To me, the most important graph is this one, showing how China’s imports of chipmaking equipment have been on a downward trend since the export controls were introduced in October 2022:

You can see that these imports were really ramping up in the late 2010s, as China worked hard toward self-sufficiency in the industry. Buying the tools to make chips is a big part of achieving self-sufficiency. Then the trend turned on a dime and seemingly hasn’t recovered since.

As Miller noted in our interview, chipmaking equipment is the hardest part of the supply chain to reproduce, because it’s so complex and has to work so consistently. The export controls are going to give China major difficulty here.

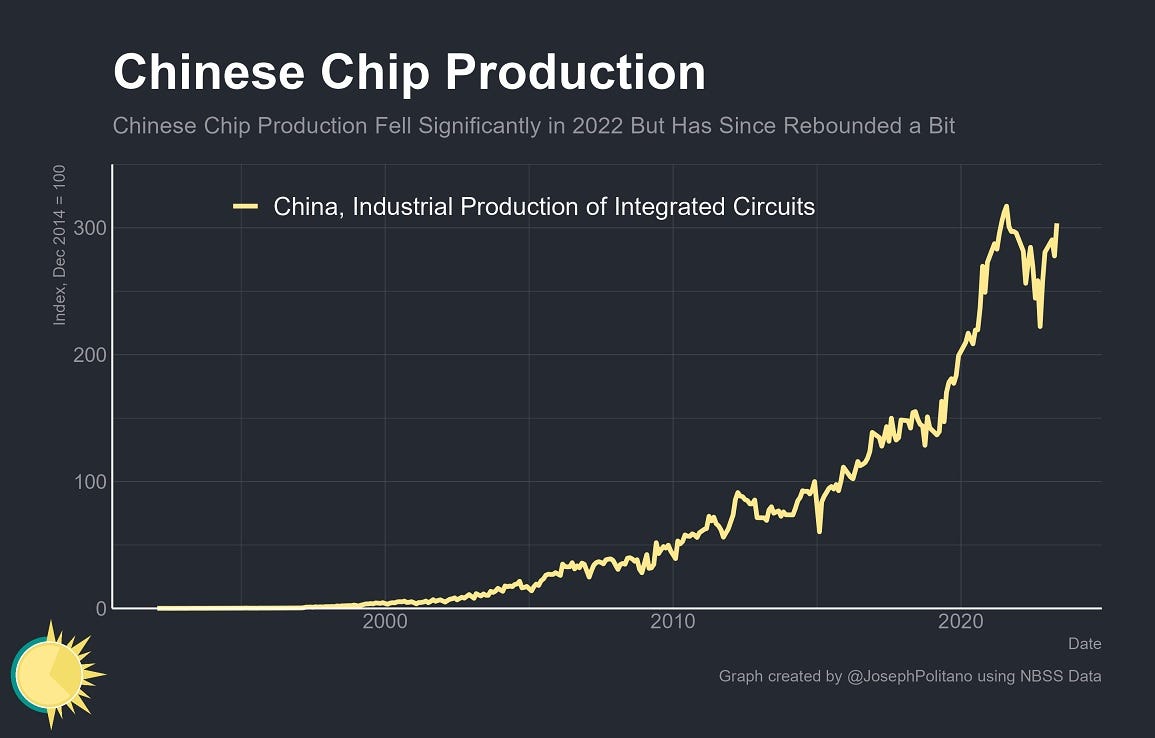

In terms of China’s actual chip production, the export controls were merely a bump in the road:

This isn’t surprising, because A) China’s government is pouring absolutely ridiculous amounts of money into chipmaking, and because B) with China now cut off from some types of imports, they have to make more of what they use. But don’t be fooled by aggregates here — the chips China is making will tend to be trailing-edge stuff, not the most advanced products. The leading edge is where the export controls are supposed to bite.

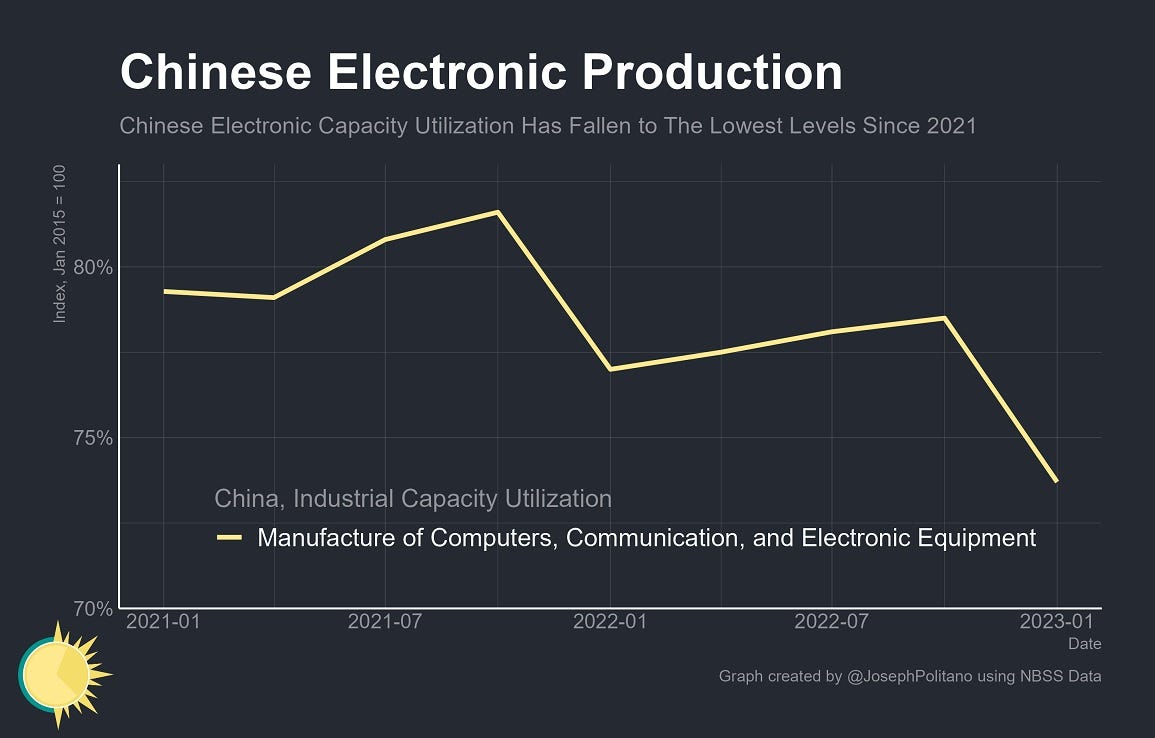

Anyway, one other interesting thing I noted in Politano’s post is that China’s electronics industry is suffering:

This is partly because of China’s general economic slowdown, of course; much of what China makes is for Chinese users, and the real estate bust is weighing heavily on the country’s domestic economy. But some of the dip between 2022Q4 and 2023Q1 might be from export controls throwing a wrench into Chinese electronics production. So that will be an interesting space to watch.

2. Where to put the housing in American cities

American cities aren’t dense enough. We need to upzone city centers and (especially) inner-ring suburbs if we’re going to avoid a crisis of affordability, especially in big coastal cities like San Francisco and NYC. The question is how best to do this, in order to create cities that feel nice to live in.

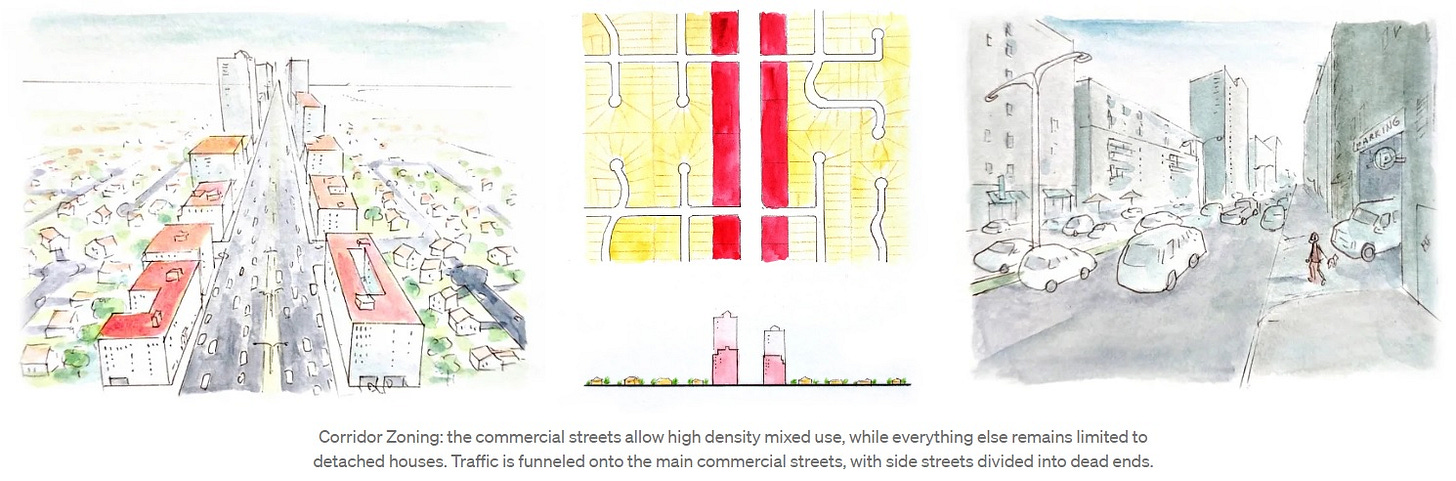

I’ve always believed that drawing pictures of cities is crucially important for helping Americans to visualize what greater density would look like. Urbanist Alfred Twu, who wrote a guest post for Noahpinion last October, is one of the best at this. In a recent blog post, Twu makes a powerful argument for why upzoning only along major streets is a big mistake:

In many North American cities, as more housing is built, it’s limited to a few places: downtown and along busy streets. This is known as Corridor Zoning…[Corridor Zoning] has downsides:

Lots of people end up living on the noisiest, most polluted streets.

Local businesses, historic buildings, and existing low-rent apartment buildings are at risk of demolition.

Storefronts on the main street are replaced by garages, exit doors, private lobbies, utility rooms and other uninviting spaces.

Limited number of sites causes land to be expensive.

Narrow canyon of tall buildings creates a wind tunnel, makes being outside on the main street unpleasant.

Twu instead recommends something called Second Street Housing:

Second Street Housing…puts the biggest new apartment buildings behind, not on top of, the main commercial strip, separated by an alley for deliveries. Further back, still within a five-minute walk, are mid-rise apartments, and beyond that, a mix of houses, duplexes, fourplexes and courtyard apartments…In most places, Second Street housing can be implemented by rezoning the land closest to commercial zones.

He illustrates the difference with a pair of drawings:

This is a great idea, because it moves us a little closer to the type of urban design that makes Japanese cities such amazing places to live. I think American urbanists, as they think about how to redesign our cities, need to have concrete simple ideas like “Second Street Housing” in mind as they move forward.

3. Where Americans are moving to (and where they’re leaving)

The Economic Innovation Group, one of my favorite think tanks, has a new analysis of Census data on population growth in American regions. Connor O’Brien has a good overview of some of the key results, with pretty maps.

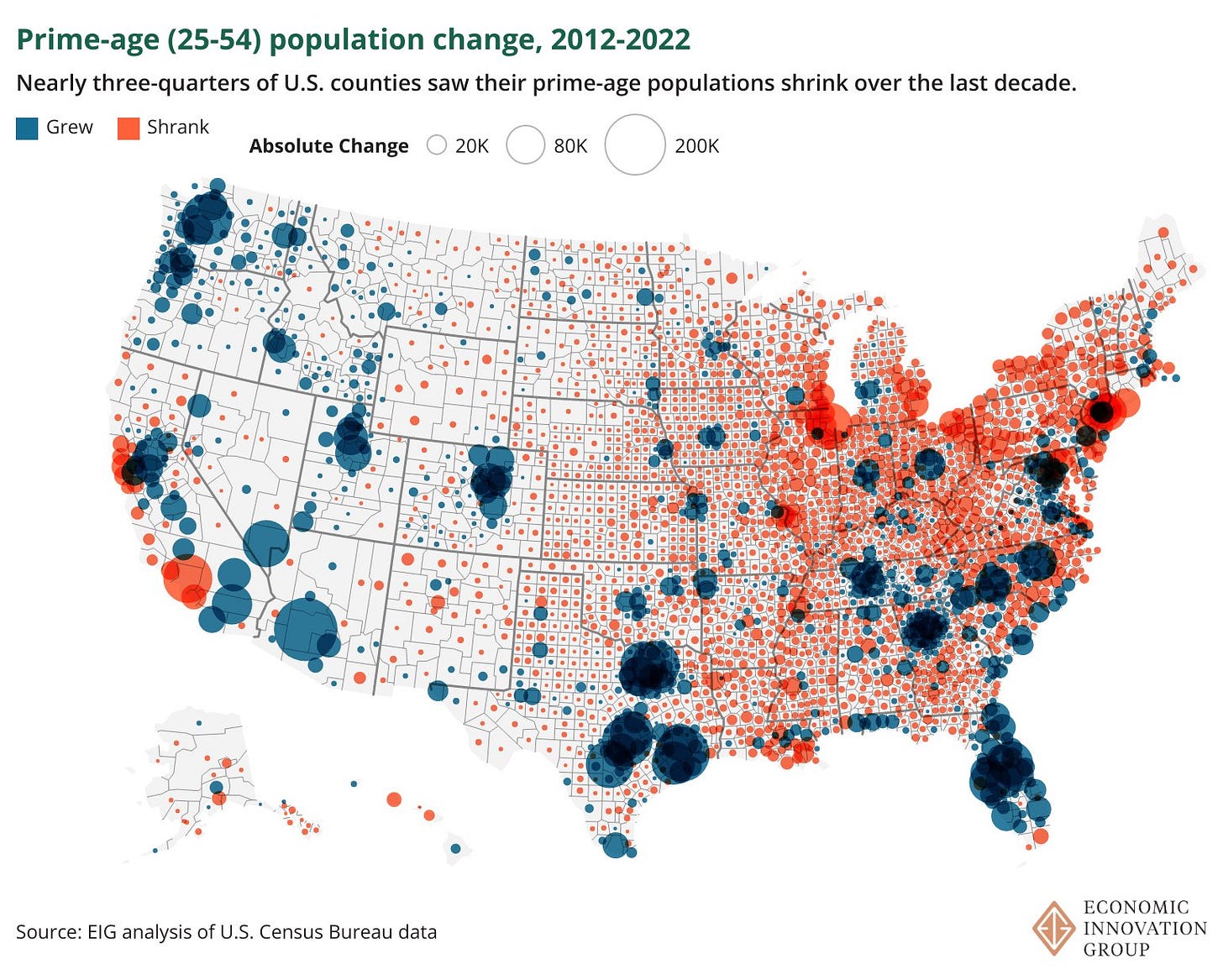

Here’s the overall map of where prime-age population grew and shrank in the U.S. from 2012 to 2022. Note that because U.S. fertility is not particularly high anywhere (even Utah), most of this growth is going to be from people moving around, rather than from births and deaths:

You can see that in general, Americans are still moving west, especially to the Rockies and beyond, and to Texas and the Southwest. The exception is the California coast, which people appear to be fleeing despite continued robust immigration from Asia and Latin America. The obvious reason is housing; California cities just don’t build much of it. Meanwhile, Americans generally continue to move from the northeast to the southeast, and from rural areas to big cities.

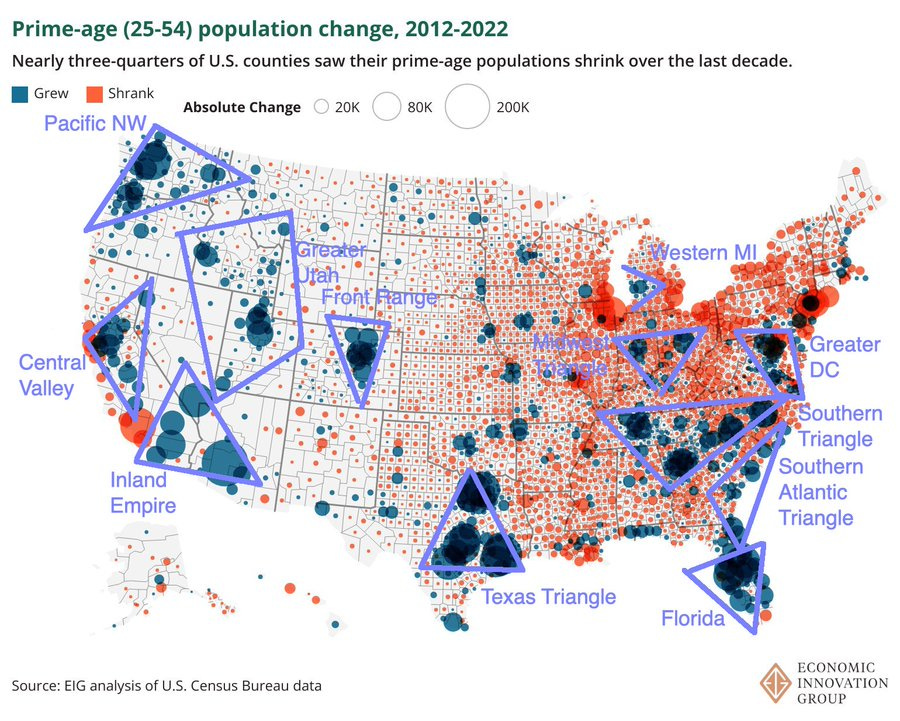

Arpit Gupta has a good thread where he labels the growth areas in the EIG data:

The big growth areas that don’t tend to get as much attention in the news are the Georgia and South Carolina coasts, and the interior South area that includes Atlanta, Nashville, Charlotte, and Research Triangle. Honestly, I think you could combine those two triangles. They include the magic combination of cheap land, sun, and good universities. Really, though, cheap land beats everything.

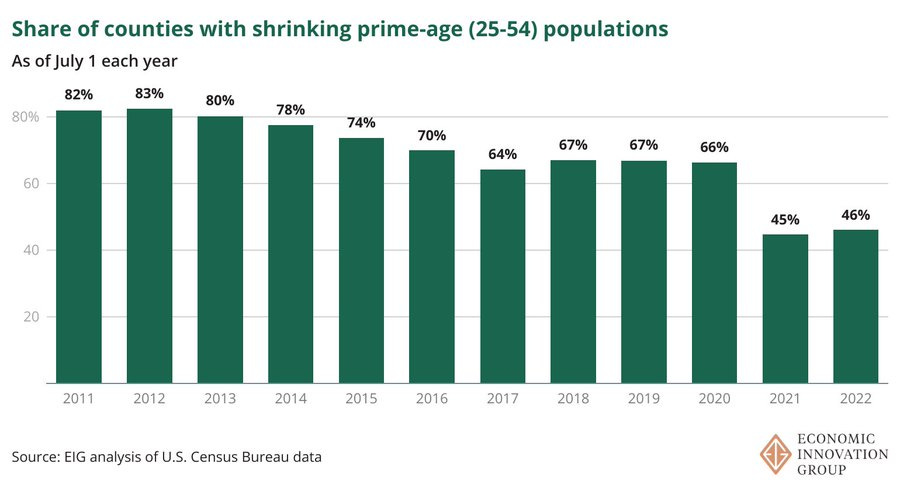

Anyway, the big question on everyone’s minds now is whether the shift to remote work — if it endures — will combine with the general shortage of housing in “superstar” cities to spread population more evenly throughout the country. There is a hint that this might be happening; since the pandemic, far fewer places in the U.S. have seen their populations shrink.

We’ll see if that continues as the “back to the office” trend intensifies.

4. How to promote exports

With the big shift to industrial policy has come a big question: How can countries promote exports? Advocates of industrial policy, like Ha-Joon Chang and Joe Studwell, believe that exports are crucial because they raise productivity growth.

Note that it’s total exports that they think are important, not net exports or trade surpluses. That’s why export promotion doesn’t have to be a beggar-they-neighbor policy — the U.S. and Japan can both sell more stuff to each other, without either one running a bigger trade deficit. What’s important, at least in the eyes of Chang and Studwell, is that you sell to world markets rather than staying within the easy safe domestic market.

A new paper by Fitzgerald, Haller, and Yadid-Levi sheds some light on how to actually accomplish this. The authors look at Irish exporters, observe their behavior over time, and see which companies fail in world markets and which succeed. Here’s their main finding:

Our estimates suggest that customer base is insensitive to lagged sales, so firms have no incentive to engage in dynamic pricing to accumulate customers. Instead, investment in customer base through marketing and advertising explains the dynamics of quantities.

What this means is that the way to build a sustainable export business isn’t to dump your products for super-cheap prices in order to gain market share. It’s to invest in marketing — in other words, to understand the local market, learn what consumers want, and figure out how to give it to them. And it’s to invest in advertising — in other words, to explain to local consumers why your product is worth paying a good price for.

Of course, this result is just a correlation, not causal. It could be that companies that spend more on marketing and advertising their products could be those who have such naturally good products that they sell themselves, while companies that have to resort to price wars tend to make crappy products that don’t have much of a future. Maybe. But Fitzgerald et al.’s result suggests a path forward for export promotion by rich countries — assist companies with marketing and advertising in foreign countries, rather than subsidizing exports monetarily.

Another advantage of a marketing-and-advertising-centric export promotion strategy is that it doesn’t violate WTO rules, as cash-based export subsidies do. So I’d advise the U.S. and Japan to try more of this approach. Remember that it’s not a zero-sum game — we can all sell more to each other, and build better, more productive companies by doing so.

5. The IRA really was a big deal

China is by far the biggest contributor to global emissions, but the U.S. is #2, and we need to do our part. Fortunately, the remarkable progress of renewable energy technology has given us a way to do that while also increasing the amount of energy we consume, rather than accepting decreases in our living standards. The Biden Administration’s admittedly somewhat-misnamed Inflation Reduction Act is a huge step toward achieving this future.

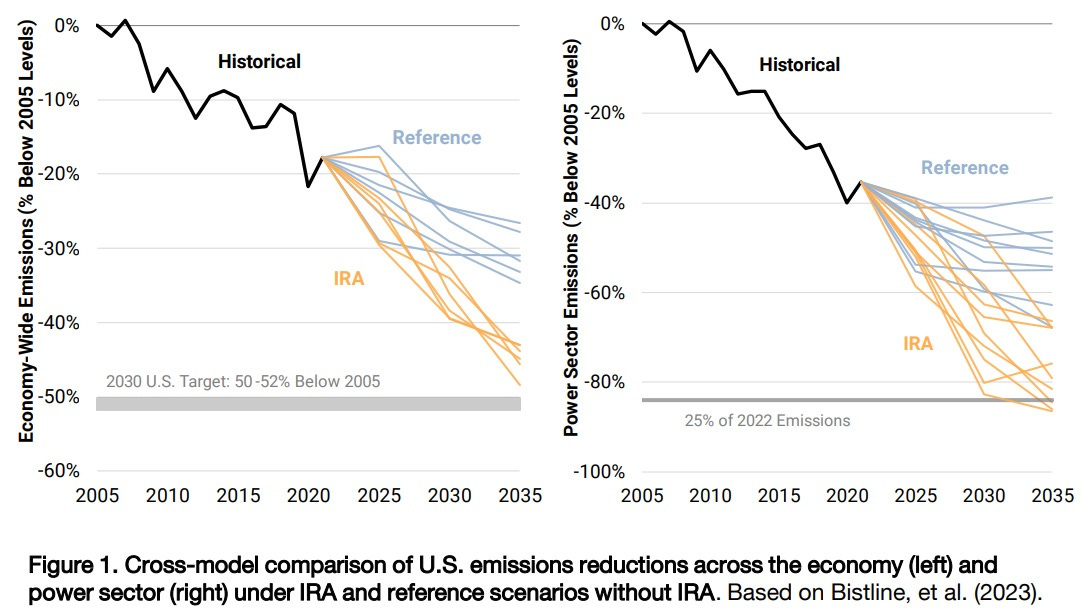

How important? A new paper by Bistline et al. in Science has some estimates. Basically, they predict that without the IRA’s green energy subsidies, the march of technological progress would reduce U.S. emissions from ~20% below their historical peak (which is what we’ve already done with fracking and energy efficiency) to ~30% below peak by 2035 — not nothing, but not enough. With the IRA, however, the authors predict we’ll be somewhere around 45% below peak by 2035 — not enough to hit our Paris targets, but not far off.

Interestingly, the biggest slice of this accelerated emissions reduction comes from the decarbonization of the power sector — not from the shift to electric vehicles. That’s probably because the initial buildout of the EV fleet will consume a lot of carbon. But the long-term impacts of the switch to EVs could still be the IRA’s most significant achievement after 2035.

It just goes to show that when the U.S. government decides to act, we can do big things, both for consumers and for the environment.

From the comments:

6. Was Larry Summers really wrong?

In the comments from last week’s roundup, John Van Gundy points me to an article by my friend Adam Ozimek, criticizing Larry Summers. In summer 2022, Summers said the following:

We need five years of unemployment above 5 percent to contain inflation—in other words, we need two years of 7.5 percent unemployment or five years of 6 percent unemployment or one year of 10 percent unemployment.

To many, it seemed like Summers was endorsing an unemployment target — i.e., that he was saying that the Fed needed to keep raising rates until unemployment reached these levels. This is not what Summers was saying, and he should have phrased his words better. What Summers was saying is that the amount of interest rate hikes that he thought would be necessary to bring inflation back down to target would end up increasing unemployment by that much.

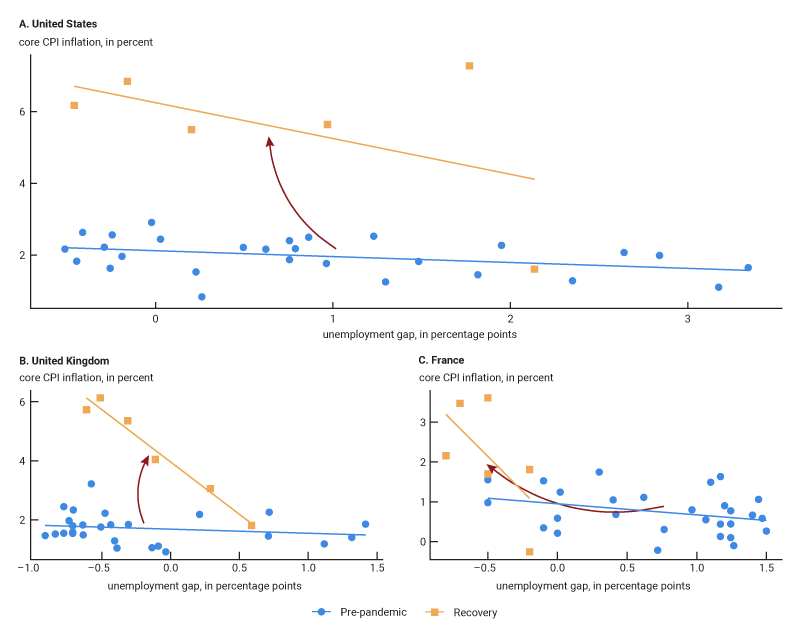

This back-of-the-envelope analysis almost certainly came from an old-fashioned Phillips Curve, which shows a short-run tradeoff between inflation and unemployment. For example, here’s a recent estimate by the Chicago Fed:

Macroeconomists argue endlessly over Phillips curves and whether they’ll hold up when policy changes. But the point is that in general, getting rid of excess inflation usually involves some cost in terms of slowing the economy and throwing people out of work. You don’t say “We need unemployment to go this high,” any more than a general on the battlefield says “We need to sacrifice this many men to take that hill.” Taking casualties isn’t what wins a battle; it’s just a cost of winning a battle. In other words, Summers was trying to prepare people for the costs of disinflation, rather than saying we should intentionally incur those costs.

As Ozimek points out, those costs aren’t a certainty. In fact, it looks as if we’ve been able to bring inflation much of the way back down (though not yet all of the way back down) without creating any noticeable amount of unemployment at all. This is called a “costless disinflation”, and it’s the dream of every central banker to achieve this. We probably had help from falling oil prices here, which Summers couldn’t have predicted back at the height of the oil shock back in mid-2022.

But note that the Fed did raise interest rates in late 2022 and early 2023, at a pretty unprecedented pace. That hasn’t yet led to any significant unemployment. So the people criticizing Larry Summers should also think about whether they overestimated the danger of rate hikes.

Thanks a ton for highlighting my piece on the chips sanctions Noah! I have been super pleased with the response to that article, and am looking at writing a lot more on the topic in the future!

Love these Noah