At least five interesting things: Nightmarica edition (#62)

American dystopia; The assault on science; Trade war eternal; Abundance and redistribution; Fertility and the draft; AI and skills; Smartphones and competence

It’s been a crazy couple of weeks, both in the policy world and with my own schedule — in Japan I was often doing 4 meetings, events, or interviews a day to promote my book, leaving me a bit less time to write. And then there was the madness of Trump’s tariffs, that crowded out pretty much everything else for a while. But I’m back from Japan, and tariff madness has calmed down a bit, and there are a lot of things I need to catch up on! I’m also jet-lagged, so I’m writing pretty late at night.

First, I’ve decided to un-paywall yesterday’s post:

All the arguments for Trump's tariffs are wrong and bad

Well, after a stock market crash, a bond market crash, and a blizzard of recession predictions, Donald Trump has paused some of his massive “Liberation Day” tariffs. But the reprieve is only partial and temporary. The very high tariff on China is still in place (and in fact has been increased). The 10% tariffs o…

Usually I just paywall every third post, pretty randomly. But some readers argued to me, convincingly, that this one deserved to be free, because behind the paywall it’s much less useful for everyday arguments. So here you go!

Next, I have two episodes of Econ 102 for you this week. In the first, Erik and I talk about Abundance, and in the second, we talk about my theory of the New Right:

Anyway, on to this week’s list of interesting things. Unfortunately, some of them are pretty dire.

1. Welcome to Nightmarica

I still remember back in 2002, when the Bush administration declared Jose Padilla an “enemy combatant” and deprived him of his legal right to trial. It was a national outrage, and rightly so. But now, 23 years later, the Trump administration is committing even worse violations of basic American civil liberties. Trump has rounded up and deported a number of Venezuelan citizens to brutal El Salvadoran prisons, accusing them of being in the gang Tren de Aragua based on nothing more than the fact that they have tattoos. In one case, makeup artist Andry Romero was deported based solely on the fact that he had a tattoo of crowns (which the administration thought was a gang symbol) on top of the names of his mom and dad.

But that’s hardly the worst case! The Trump administration also deported a man named Abrego Garcia to El Salvador completely by accident, then claimed they didn’t have the ability to bring him back:

The Trump administration acknowledged in a court filing Monday that it had grabbed a Maryland father with protected legal status and mistakenly deported him to El Salvador, but said that U.S. courts lack jurisdiction to order his return from the megaprison where he’s now locked up…

Abrego Garcia, who is married to a U.S. citizen and has a 5-year-old disabled child who is also a U.S. citizen, has no criminal record in the United States, according to his attorney. The Trump administration does not claim he has a criminal record, but called him a “danger to the community”…

He works full time as a union sheet-metal apprentice, has complied with requirements to check in annually with ICE, and cares for his 5-year-old son, who has autism and a hearing defect, and is unable to communicate verbally.

On March 12, Abrego Garcia had picked up his son after work from the boy’s grandmother’s house when ICE officers stopped the car…Within two days, he had been transferred to an ICE staging facility in Texas…Abrego Garcia’s family has had no contact with him since he was sent to the megaprison in El Salvador, known as CECOT…

“Oopsie,” [Salvadoran President Nayib] Bukele wrote on social media, taunting the judge [who had ordered the Trump administration to stop the deportation flights].

This sounds pretty similar to the beginning of the dystopian 1985 movie Brazil, in which an innocent man named Buttle is randomly arrested and killed in prison because of a typo on an arrest warrant for a man named Tuttle:

The error in real life isn’t quite the same as the typo in the movie. But what the Trump administration is trying to do — to seize a hard-working peaceful family man, who has not been accused of any crime, and to throw him into a hellish torture dungeon for the rest of his life — is very similar. Imagine, for a moment, that this was you, or your father. Now see if you can come up with a convincing argument as to why it never will be.

The Supreme Court, presented with the case, ordered the Trump administration to “facilitate” Garcia’s return to America, but gave no deadline. The administration is arguing that there’s nothing it can do — that Garcia has to spend the rest of his life in that dungeon because of their mistake.

Is this the America you grew up in? Maybe if your awareness of current events started with Padilla and Guantanamo and the War on Terror, it might feel like the arrests of Garcia and Romero are simply a minor evolution in the saga of American authoritarianism. But I remember a time when this kind of thing felt unthinkable, and was the merely the plot of dystopian fantasies.

Even Joe Rogan, one of Trump’s most prominent supporters in the media, was rightfully horrified by this turn of events:

Joe Rogan said it’s “horrific” to think that non-criminals could be lumped in with violent migrant gang members and shipped off to maximum-security prisons in Latin America…

“The thing is, like, you got to get scared that people who are not criminals are getting, like, lassoed up and deported and sent to, like, El Salvador prisons,” the podcaster said to his guests…“This is kind of crazy that that could be possible. That’s horrific. And that’s, again, that’s bad for the cause,” Rogan said…“And then, like, how long before that guy can get out? Can we figure out how to get them out? Is there any plan in place to alert the authorities that they’ve made a horrible mistake and correct it?”

Good for Rogan. It’s nice to know that even some of Trump’s supporters can see what his second term is becoming. But I don’t know if that’ll be enough to stop the descent into authoritarian nightmare.

2. Trump’s war on science

So far, a lot of Trump’s actions in his second term seem almost intentionally designed to weaken the U.S. economy and American power in general. I highly doubt this is actually deliberate, of course, but the consistency so far is uncanny.

The tariffs are the most conspicuous and the most disastrous instantiation of this, of course, but they aren’t the only thing Trump is doing. There’s also Trump’s attacks on the institutions of U.S. research and development. Matt Yglesias had a great post about this a couple of weeks ago:

As examples, Yglesias points out deep cuts to the federal workforces responsible for administering grant money, rules that limit government funding for science, RFK’s war on vaccines, attempts to cut or discourage high-skilled immigration, and so on.

The purpose of this assault, of course, is ideological. Trump and his people believe that U.S. scientific institutions — universities, granting agencies, and so on — have all been captured by what Elon Musk calls “the Woke Mind Virus”, and that they have to be purged as a result. If you look at which grants are being cut the most, it’s AIDS research, research on trans people and on Covid, climate research, and other topics that are considered “woke”.

Perhaps you think America could use less of this type of research. Fine. But purges rarely leave the purged institutions stronger, and Trump’s attempts to root out woke ideology will likely leave American science poorer than before. And the ham-handed way that Trump has slashed NIH funding across the board is likely to hit far more than just the “woke” parts of science. Sure, trans research is getting slashed, but cancer research is getting slashed too. NSF research is being cut across the board, not just on things like climate science.

Running a nation on ideology is just always a bad idea. Surely there were ways to bring American science back to a politically neutral stance without smashing it. But sadly, this administration is a “smash first and ask questions later” kind of outfit.

3. Tariffs now, tariffs tomorrow, tariffs forever

The Trump administration often touts tariffs as a way of exchanging short-term pain for long-term gain. Yes, there will be disruption in the short term, they argue, but once manufacturing returns to American shores and trade deficits disappear, prosperity will be supercharged.

That was always incredibly unlikely to be true. If it were, we’d probably see stock markets up since Trump’s election instead of down, since stock markets are forward-looking. And as I explained in my last post, broad-based tariffs are simply incredibly unlikely to reindustrialize America, now or ever.

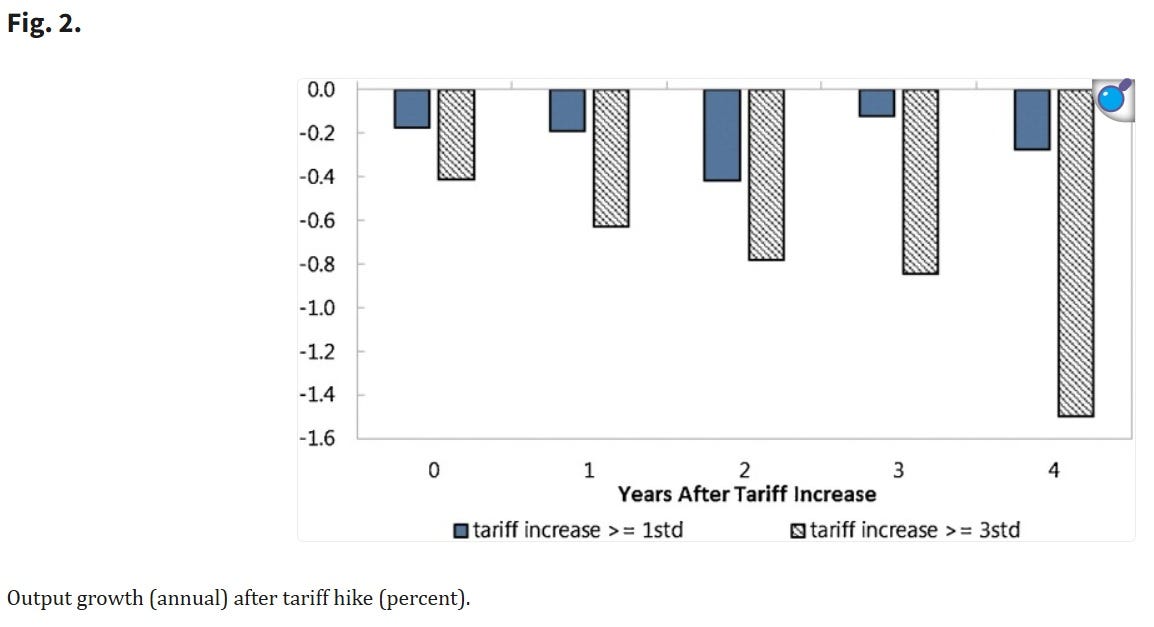

Evidence shows that this tends to be the case. You can just look at cases where countries raise tariffs by a substantial amount, and see what happens to their economies. This is what Furceri et al. (2020) do, and they find that GDP tends to go down after a big tariff hike. And for very large tariff increases, the magnitude of the output decline increases as the years go by — the long-term pain is worse than the short-term pain.

Plenty of other research, finds similar results, of course. And when you remove poor countries from the sample, the effect is even more stark; tariffs seem to lead to worse outcomes for rich nations than poor ones.

Of course, the causality could be reversed here; countries that are in economic trouble might tend to be the ones that resort to tariffs, and the tariffs might simply not be enough to save the countries’ economies. In macroeconomics it’s very hard to isolate causality. But the facts seem consistent with the standard story, in which both A) a loss of specialization in production, and B) deindustrialization from the soaring cost of intermediate goods leads to long-term pain. On top of that, as Tyler Cowen writes, erratic tariff policies like Trump’s probably cause uncertainty that hurts business investment.

The part about deindustrialization is especially important, because it undercuts the core beliefs of Trump and the MAGA movement. As Baqaee and Malmberg (2025) show, any simple model in which capital goods get taxed at higher rates is going to show less capital accumulation over time — in other words, deindustrialization.

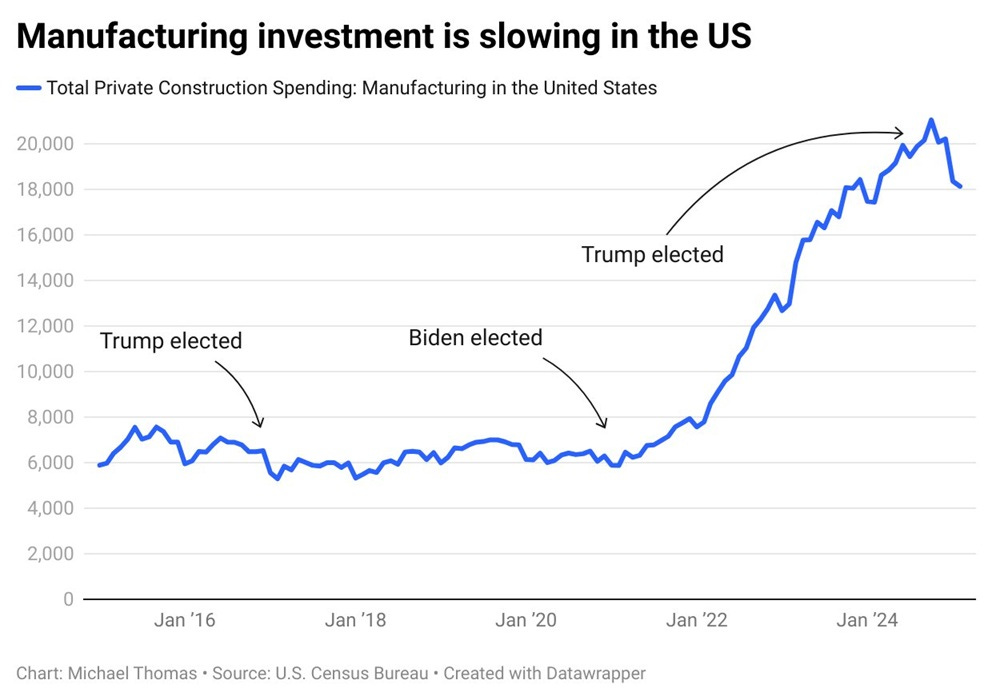

If this were counteracted by industrial policy and export promotion, it might be fine. But Trump is canceling Biden’s industrial policies and shows no interest in promoting exports (which will be hurt by tariffs and by other countries’ retaliation). Already, we see factory construction slowing down under Trump:

People who simply take it on faith that tariffs boost U.S. domestic manufacturing, like Michigan’s Democratic governor Gretchen Whitmer, need to realize that the opposite is often true, especially when the tariffs fall on capital goods and intermediate goods. This is not a policy that will revive Michigan, or the Rust Belt, or the blue-collar workforce, or the forgotten man of America.

4. Yes, abundance includes redistribution

Leftist critics of the Abundance movement often claim that it’s a Trojan horse for business interests and libertarianism. Maxwell Tabarrok agrees, arguing that Ezra Klein and Derek Thompson’s book implies that we don’t need redistribution:

[T]o sneak past the defenders of progressive orthodoxy, Ezra and Derek must hide the most radical parts of their message…If you really believe that there can be industrial revolution-level growth over the next several decades leading to massively increased per capita incomes, energy consumption, and a slate of new technologies and medicines which improve and extend life, then there’s just nothing you can do with redistribution today that would come close to the importance of this progress…

Redistribution doesn’t matter in [Klein and Thompson’s preferred] future. Gains to human welfare come from new inventions and from technological progress lowering the cost of all the goods we want more of today, like housing, medicine, and energy.

This isn’t an argument against Abundance; it’s a libertarian attempt to hijack the idea for its own goals. But like most of the anti-Abundance arguments, Tabarrok’s doesn’t hold up.

The reason is simple and conceptually easy to understand: Growth and redistribution are not substitutes. The more you grow the pie, the more pie you have to divvy up.

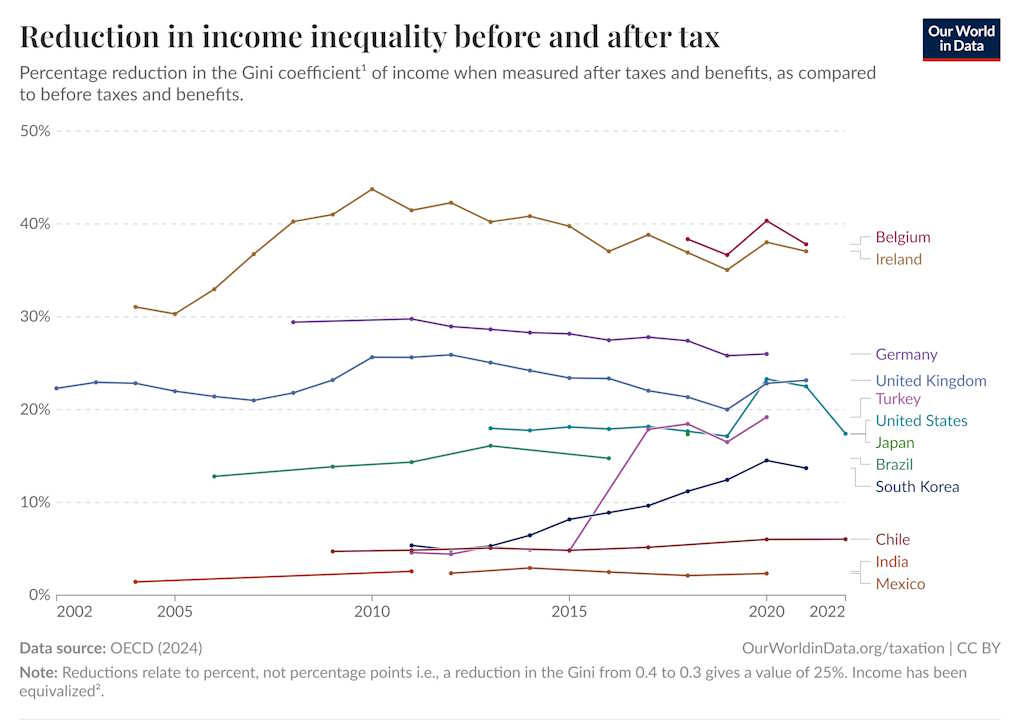

In fact, this is what tends to happen when countries get richer. Every rich society on Earth, including the U.S., does a significant amount of government redistribution. You can see this in many data sets, but an easy way is to look at the reduction in income inequality from countries’ tax and transfer systems:

As you can infer from this chart, government redistribution is very important for the material living standards of low-income people in rich countries. Without redistribution, they’d be much, much poorer. Also, with the examples of India and Mexico, the chart hints at another important fact: Rich countries redistribute more of their GDP. There are very few poor countries that do a lot of redistribution.

So yes, creating abundance and growth will tend to lead to more redistribution, not less. And this redistribution will be very significant for the livelihoods of the people in the countries that embrace abundance.

5. Did we find a way to increase fertility rates?

One of the biggest puzzles in the policy world is how to raise fertility rates. Population aging is a huge problem, and moderately higher fertility is the only real solution to that problem. But no country so far has found affordable and effective pro-natalist policies:

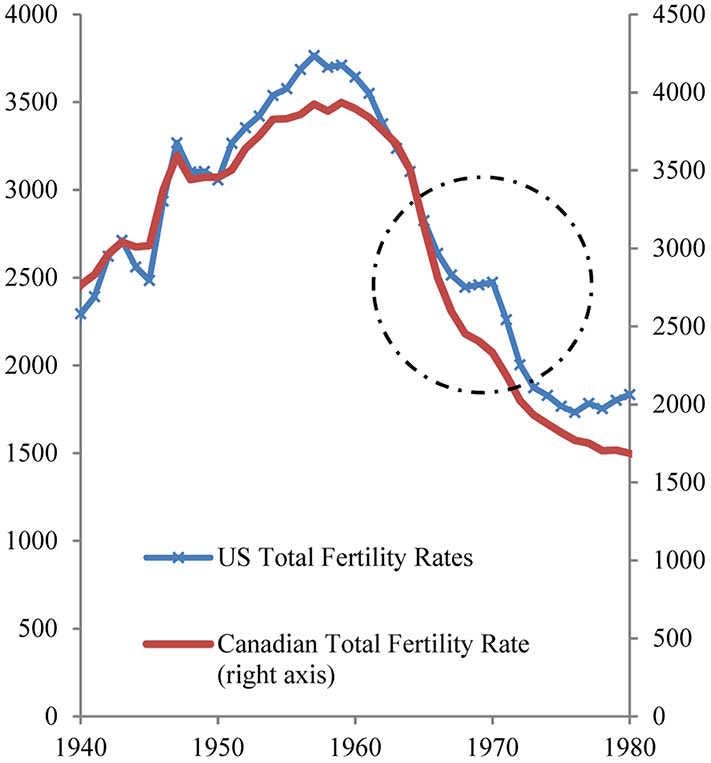

…Or have they? On X, Carlos Mucha flags a couple of papers that suggest that if you allow men to avoid the draft by having kids, fertility rates go way up. For example, Bailey and Chyn (2021) find that the U.S. government policy of allowing men with kids to get out of the Vietnam War draft led to a very large bump in U.S. birth rates relative to countries like Canada that didn’t have a Vietnam War draft:

This paper provides time series evidence that the availability of hardship deferments led to large increases in U.S. fertility rates in the late 1960s, producing a fertility notch driven by elevated numbers of first births (hardship deferments required one child) among women in their early twenties (likely to be partnered with draft-eligible men). Following President Nixon’s Executive Order eliminating paternity as grounds for hardship in April 1970, fertility rates plummeted—especially for women who were likely to be partnered with draft-age men.

And here’s a chart:

Obviously, going to war is probably not a viable strategy for raising the birth rate. But this piece of historical evidence suggests that while rewarding people for having more kids is of limited use, punishing them for not having kids may be a lot more effective.

Meaning that if fertility keeps trending down, I would expect to see nations try some fairly dystopian pro-natalist policies.

6. Does AI help low-skilled people or high-skilled people?

UPDATE: Aaron Toner-Rodgers’ paper, mentioned in this section, turned out to be a complete fraud!

One of the economic debates about AI technology is whether AI tends to compress the skill distribution or widen it. In other words, does AI provide a substitute for human intelligence, allowing low-skilled folks to catch up with their higher-skilled counterparts? Or does AI complement human intelligence, allowing the best and the brightest to zoom ahead because they know how to use AI better?

For a while, all the research seemed to agree that the former happened more often. Paper after paper found that AI helped low performers a lot more than it helped high performers:

But The Economist recently flagged a couple of papers that find the opposite. Toner-Rodgers (2024) finds that AI boosts top researchers more than it helps mediocre researchers:

[AI] technology has strikingly disparate effects across the productivity distribution: while the bottom third of scientists see little benefit, the output of top researchers nearly doubles. Investigating the mechanisms behind these results, I show that AI automates 57% of “idea-generation” tasks, reallocating researchers to the new task of evaluating model-produced candidate materials. Top scientists leverage their domain knowledge to prioritize promising AI suggestions, while others waste significant resources testing false positives.

And Otis et al. (2023) find that AI helps top Kenyan entrepreneurs more than it helps the others:

While we find no average treatment effect, this is because the causal effect of generative AI access varied with the baseline business performance of the entrepreneur: high performers benefited by just over 20% from AI advice, whereas low performers did roughly 10% worse with AI assistance. Exploratory analysis of the WhatsApp interaction logs shows that both groups sought the AI mentor’s advice, but that low performers did worse because they sought help on much more challenging business tasks.

Both of these results basically come from AI’s limitations. Toner-Rodgers finds that AI complements top researchers because it automates away simpler tasks, leaving them to focus on more complex tasks that AI still can’t do very well. Otis et al. find that AI fails to help lower-skilled entrepreneurs because they ask AI questions that it’s not yet good enough to handle.

As AI improves, though, both of these effects should weaken. As AI becomes more capable of doing more advanced research tasks and answering more sophisticated business questions, its inequality-magnifying effect should fall. Eventually, if AI keeps getting better, more and more tasks will look like those in the previous crop of papers — simple things like writing college essays and answering customer support calls. Thus, the more AI substitutes for human intelligence, the more I think we can expect it to compress the inequality due to human skill differences.

7. Smartphones and the crisis of competence

I recently found out that my favorite tea shop (Red Blossom Tea in Chinatown, San Francisco) is going to be closing in a year. When I asked them why, one reason they cited was the difficulty of finding good help. Young people, they told me, were simply incapable of the kind of conscientiousness needed for their business — even graduates from top schools made frequent mistakes, couldn’t take criticism, and were constantly distracted by their phones.

This fits with anecdotes I’ve been hearing from a lot of other people. Here’s an especially cutting blog post about the phenomenon:

Of course, older people often tend to call the youth lazy and spoiled — and indeed, the preference for leisure, including the hidden leisure of working less hard at your job, might rise with income. But there’s also another theory here, which is that smartphones are uniquely deleterious to conscientiousness, intelligence, and task performance. Here’s what the pseudonymous author of the above post has to say:

It’s the phones, stupid. They are absolutely addicted to their phones. When I go work out at the Campus Rec Center, easily half of the students there are just sitting on the machines scrolling on their phones. I was talking with a retired faculty member at the Rec this morning who works out all the time. He said he has done six sets waiting for a student to put down their phone and get off the machine he wanted. The students can’t get off their phones for an hour to do a voluntary activity they chose for fun.

This certainly fits with the evidence I showed in my last roundup, that problem-solving and information-processing among young people started to plummet in various rich countries right around the time the smartphone was introduced.

I’m always wary of “theories of everything”, but it feels like we’re rapidly approaching a “smartphone theory of everything” when it comes to the problems of rich-world youth:

In any case, we need a lot more evidence before we conclude that “it’s the phones, stupid.” But it’s seeming more plausible by the day.

Re phones: it’s absolutely them, but I would zero in further on the ubiquitous mechanic of the Feed. No matter where you find it (X, Facebook, Reddit, now on Substack) the Feed is a high-cardinality information flow - you get the hilarious, the outrageous, the baffling, the poignant, the enraging all at once in a never ending barrage that the human mind did not evolve to handle and easily becomes addicted to. For the last six months I’ve done an experiment on myself: I’ve stopped spending any time with any app or site that has that mechanic as its main interaction point.

The result is that I feel myself returned to an ability to contemplate, to be still, to spend more time reading books and magazines and other long-form pieces without interruption. Frequently a lot of that reading happens on my phone, but it’s not kicked off by encountering something on a Feed.

I’m never going back.

Couple thoughts:

1.) Regarding MAGA’s war on American science—It is going to shrink the U.S. as a global power, but they see that as a net “good”.

A shrunken, stunted America where they control everything in a vice grip is, in their minds, far preferable to a strong, prosperous America where they are one voice among many, drowned out by the more cosmopolitan and educated among us.

They would rather rule over a ruin than share power in an empire. They would rather be a big fish in a small pond than a medium-sized fish in a teaming lake.

There are many drivers behind that misanthropy—Boredom with prosperity, simple jealousy, religious fanaticism, existential angst—but it’s the one lodestar that seems to adequately explain how self-destructive, how vengeful and purposelessly nihilistic, MAGA is.

It also explains why a small but critical faction of the far left is either ambivalent or outright allied with MAGA. The “big fish little pond” mentality is, if nothing else, what drives Jill Stein, and what drove Ralph Nader in the past. But that’s a subject for a whole new thread.

2.) I don’t think Gretchen Whitmer herself consciously, sincerely believes tariffs will lead to a “revival of manufacturing”.

I think she’s just trapped by the essential fantastical world that one must vocally buy into if one is to be a successful local politician, in certain places.

In Michigan, you cannot get elected if you do not repeat the catechism that “NAFTA is the worst thing to ever happen to manufacturing jobs.”

You cannot gain purchase with any number of voters if you do not talk about free trade and free flow of goods as if it were the Devil himself. They simply do not want to hear you.

I think it’s not so much a matter of economic reasoning for those voters, quite honestly, as it is an issue of loss and grief.

They’re not looking for politicians or leaders that will maximize their prosperity or well-being. (They tried that stuff; it was dissatisfying.)

They’re looking for leaders who will channel their sense of anger at losing the past, angst at the passage of time. They feel they were wronged by change, writ large, quite simply, and they want punishment.

When Whitmer does things like give qualified praise to Trump’s trade war, she’s appealing to that emotional, glandular vibe in her voters, not making a reasoned economic argument about manufacturing and trade. She’s, again, kinda trapped by it.

Honestly, I have no idea what to do about dysfunctional politics like that.

Electing other leaders, and empowering other, less fantasy-driven voters, is a start, I guess. (Jared Polis, for all his (mild) faults, is a good counter-example.)