At least five interesting things for the middle of your week (#40)

Europe's Greens; jobs and the Great Replacement; tariffs and development; rent control; service costs

Hello, excellent readers! It’s election season, so a lot of what’s in the news these days — including the econ blogosphere — is about Trump vs. Biden. That makes it a bit harder for a writer like me — everything is very contentious, there’s a lot of misinformation going around, and it gets harder to talk about policy because everything depends on who wins. Nevertheless, I will do my utmost to continue to deliver you interesting and relevant content in these trying times.

This week’s episode of Econ 102 features special guest Kyla Scanlon, an econ writer who coined the term “vibecession”, and author of the book In This Economy?: How Money & Markets Really Work. We have a very lively and cordial discussion!

Anyway, on to this week’s list of interesting things.

1. Europe is starting to realize that degrowth is bad

The European Parliament just held elections, and everyone is talking about how far-right parties gained a lot of ground. But the other big story is the decline of the Green party, which is projected to have lost about a quarter of its seats since 2019, with especially big losses in France and Germany. The general consensus seems to be that European voters are not in a mood to prioritize the fight against climate change over bread-and-butter issues:

In Germany, a core Green stronghold, the party’s vote share appears to have nearly halved since the last election in 2019. Exit polls suggested it fell 8.5 percentage points from 20.5% to 12%. In France, where the far right was leading and President Emmanuel Macron called snap elections, support for the Greens fell by the same amount…

[The Greens] have traditionally been buoyed by younger voters, some of whom now appear to have drifted to the far-right Alternative für Deutschland (AfD), as well as newer parties…

Political scientists doubt there has been a widespread backlash against European climate policy, but warn that badly designed measures – particularly ones that hit poorer households hardest – can backfire.

Though no one seems to be using the word, the key problem here seems to be degrowth. Although the idea of making people poorer in order to fight climate change thankfully doesn’t seem to have taken root in the U.S. (beyond the occasional glowing uncritical writeup in the New York Times), European intellectual elites seem to find the concept quite seductive. Some Green party supporters even asserted that their party lost because they didn’t push degrowth hard enough:

This is, of course, totally blinkered and out of touch. In reality, European voters are upset precisely because their societies are degrowing:

"Improving the economy and reducing inflation" ranked highest among citizens asked what was the most important thing influencing their vote, in a survey by polling platform Focaldata, shared with Reuters…"International conflict and war" was the second most important concern, followed by "immigration and asylum seekers"[.]

Although East Europe has seen robust catch-up growth, living standards in the core European economies of France and Germany have been lagging behind the U.S.:

In 1990, France’s per capita GDP was 83% of the U.S. Now it’s down to 71%. And the divergence has only accelerated since the pandemic, with the U.S.’ recovery outpacing Europe’s by leaps and bounds:

These are abstract numbers, but they correspond to a reality on the ground where Europeans’ daily lives are gradually becoming shabbier and more difficult:

The French are eating less foie gras and drinking less red wine. Spaniards are stinting on olive oil. Finns are being urged to use saunas on windy days when energy is less expensive. Across Germany, meat and milk consumption has fallen to the lowest level in three decades and the once-booming market for organic food has tanked…Adjusted for inflation and purchasing power, wages have declined by about 3% since 2019 in Germany, by 3.5% in Italy and Spain and by 6% in Greece. Real wages in the U.S. have increased by about 6% over the same period, according to OECD data.

The reality is that Europe is already embracing degrowth — perhaps not intentionally, but in actual fact. And this is not only making Europeans poorer, it’s making the region much more vulnerable to the imminent threat of a China-backed Russian invasion.

The Greens’ message to Europeans is essentially that this is a good thing — the necessary price of reducing carbon emissions a little bit faster — and that what the region needs is more of the same. European voters are not having it.

2. No, Americans aren’t being “replaced” by foreigners in the job market

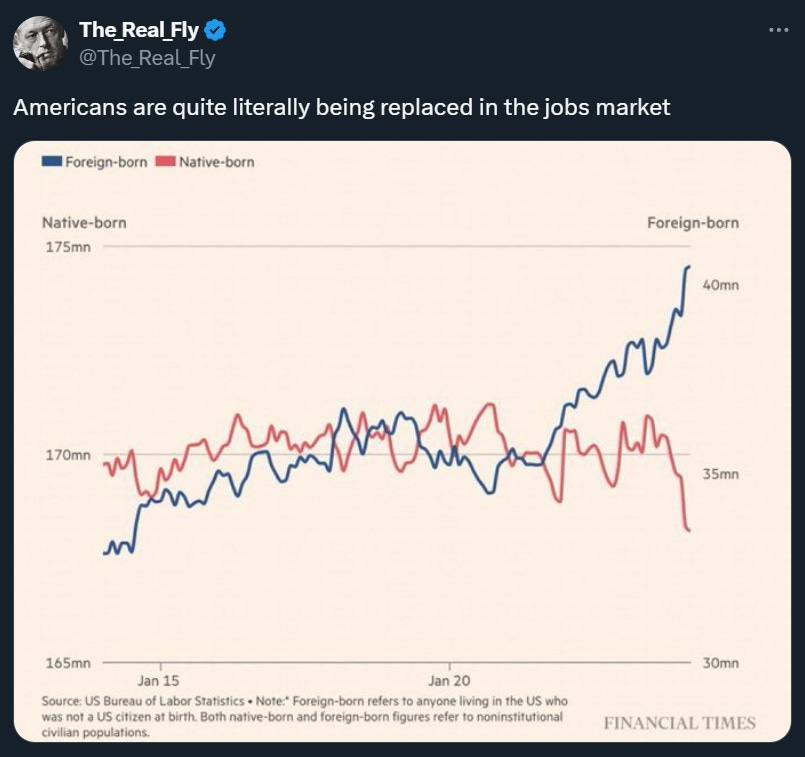

A bunch of Trump supporters are promoting the idea that immigrants are “replacing” native-born Americans in the job market:

Right-wing accounts on Twitter have been pushing the idea that immigrants are pushing Americans out of the job market for months. Now a clumsily made chart by the Financial Times is inadvertently helping them spread the misconception.

Let’s apply our techniques for analyzing viral charts. Note that this chart has two different y-axes — not just different in levels, but different scales as well. This makes the decrease in the native-born labor force look like the mirror image of the increase in the immigrant labor force. It also makes it look like the native-born labor force is absolutely plummeting. But neither of those are true. If you put the two lines on the same y-axis, you can get a clearer picture of what’s really going on:

The native-born workforce is just about as big as it was before, while the foreign-born workforce is much smaller and has increased by a small amount.

And if we look at the percentage of prime-age native born workers who have jobs, it’s actually higher than it was under Trump!

The small drop in the native-born labor force participation rate since the pandemic is thus due entirely to people over the age of 54 — in other words, people taking early retirement. And the long stagnation of the total size of the native-born workforce is due to the Baby Boomers retiring and not leaving behind many kids.

In other words, the MAGA talking point that immigrants are pushing native-born Americans out of the workforce is complete bunk. They must think we don’t know how to read a chart.

3. Tariffs on China could help the rest of the developing world industrialize

British pundits — and even a few American pundits — continue to inveigh against Biden’s tariffs on Chinese products, while utterly ignoring the central rationale behind the tariffs. Searching their jeremiads for words like "military", "defense", and "national security" turns up a complete blank. Because they don’t even address the most important reason for tariffs, their arguments against the tariffs can’t be taken very seriously.

But on top of that, there’s another important piece of the story that the tariff critics are missing. Tariffs provide a big incentive for production to move out of China. But that doesn’t mean it’ll move to the U.S. — instead, it’ll move to developing countries like India, Mexico, Vietnam, Indonesia, the Philippines, and so on. Arvind Subramanian, a development economist, writes:

What is often missing from the debate about the escalating rivalry between the United States and China is the perspective of other countries, especially larger developing economies. After all, these tariffs are not just protectionist but also discriminatory…[T]oday’s tariffs are being imposed on imports from perceived adversaries like China, redirecting economic activity toward third-country suppliers considered allies…

India offers a prime example. It has successfully attracted several Western firms exiting China since launching its “China Plus One” strategy in 2014. Notably, Apple has significantly expanded its iPhone manufacturing operations in India, and Tesla reportedly may follow suit…If India can establish a supply chain that is largely independent of China – a trend that is slowly underway in the electronics sector – it could gain a competitive advantage over China and countries linked to it…

[T]he greater the overlap between America’s strategic interests and third countries’ capabilities and comparative advantages, the more likely that discriminatory protectionism will be long-lasting and provide certainty to investors seeking to diversify away from a ruthlessly efficient China.

Subramanian is right, of course, but I think even he doesn’t go far enough! Subramanian focuses only on Western companies moving production outside of China, and thus he argues that countries like Vietnam and Indonesia, whose supply chains are more integrated with China’s, will benefit less. But this ignores the possibility that these countries will benefit from Chinese companies moving production out of China.

Currently, Biden’s new tariffs are only on China. That means if Chinese companies like BYD build factories in Vietnam, they can circumvent the tariffs as currently written. Eventually the U.S. may plug that seeming loophole (though Europe may not). But in the meantime, there’s a big incentive for Chinese companies to go build factories in other countries. And in fact, this is exactly what they’re doing:

In fact, Chinese companies are investing in India too, despite worries that in the long term this will help India become an economic rival to China. In the end, individual incentives usually trump nationalist concerns.

Even if you ignore the national security aspect of the issue, you should agree that companies moving production from China to India, Vietnam, Indonesia, etc. is a very good thing. These countries are much poorer than China, meaning they need the growth much more than China does:

In the end, both Western and Chinese companies moving factories to a new round of developing countries is just another instance of the old “flying geese” theory of development. But in this case, the geese needed a little extra push to get them out of China. Tariffs provided that push, and the global poor could benefit greatly as a result.

4. Rent control has real costs

In my observation, renters, and people like YIMBYs who are dedicated to make life easier for renters, are strongly attracted to the idea of rent control. After all, the thing causing immediate pain to renters is…well, rent increases. So there’s an understandable to desire to just ban the painful thing, to make the immediate pain go away.

There’s a general understanding that rent control might have some negative long-term consequences for renters — that the policy might be a temporary crutch that makes things worse down the road. But now is now, and tomorrow is tomorrow, and it’s always tempting to find reasons to convince yourself that the short-term benefit comes without costs.

But the reality is that the long-term costs are usually there. Konstantin Kholodilin has a very large new literature review of studies on rent control — here’s a spreadsheet of all the studies he cites — and he concludes that the downsides are very real:

Is rent control useful or does it create more damage than utility?…This study reviews a large empirical literature…Rent controls appear to be quite effective in terms of slowing the growth of rents paid for dwellings subject to control. However, this policy also leads to a wide range of adverse effects affecting the whole society…

[A]ccording to the studies examined here, as a rule, rent control leads to higher rents for uncontrolled dwellings. The imposition of rent ceilings amplifies the shortage of housing. Therefore, the waiting queues become longer and would-be tenants must spend more time looking for a dwelling…

Likewise, the influence of rent control on new residential construction and supply seems to be similar. Approximately two-thirds of the studies indicate a negative impact, while several studies discover no statistically significant effect whatsoever…[V]ariations in the design of rent control policies can matter…[N]ewly constructed housing could be exempted from control, thus remaining unaffected by rent control regulations…

The published studies are almost unanimous with respect to the impact of rent control on the quality of housing. All studies, except for Gilderbloom (1986) and Gilderbloom and Markham (1996), indicate that rent control leads to a deterioration in the quality of those dwellings subject to regulations.

So while rent control provides lots of benefits for the people lucky enough to live in rent-controlled units, it causes the overall housing stock to be smaller and shabbier. And it hurts people who don’t live in rent-controlled units, both by raising their rents and by making it harder for them to find a place to move.

That doesn’t mean rent control is never worth the price. But it means there is a price, and people who advocate rent control need to think about it.

5. Service costs are increasing more slowly these days

Remember that chart that showed services like health care and education becoming much less affordable in America?

This is generally a very good and important chart. It’s not a perfect chart — it overstates college costs because it ignores financial aid, and its data source probably understates the recent drop in tuition. Also, it puts housing in the red because housing went up in price in an absolute sense, even though wages went up by more. But these are minor quibbles — overall, the chart accurately conveys the fact that since the turn of the century, big-ticket services have gotten less affordable, even as many physical goods became more affordable.

But when you make “percentage increase” charts like this, the starting year you choose is very important. If you change the starting year, the trend often looks very different. And as Jeremy Horpedahl points out, many of the big-ticket services that have gotten more unaffordable since 2000 have actually gotten more affordable since 2013:

Hospital services are the big outlier here, but medical care in general has become a bit more affordable, as have college, day care, and housing. That’s great news. It holds out some hope that the big service cost increases of earlier decades were a one-time phenomenon that’s not going to be repeated.

Of course, that doesn’t change the fact that we should look for ways to make health care, education, and housing more affordable. But it means that the headwinds stopping us from doing that may now have slackened. And it’s an important reminder that economic trends aren’t set in stone.

To what extent is the decline of Europe's Green parties in the recent EP elections a result of Europeans beginning to see through what I'd call the "Green-Left lie" -- namely the notion that environmentally-meaningful degrowth would be possible only at the expense of "the rich".

This of course isn't the case, because while multi-millionaires may live highly profligate lifestyles, their consumption of physical resources is far less (as a multiple of what ordinary people would use) than their paper net worth is, and certainly doesn't compensate for their minuscule share of the total population. Millionaire wealth is overwhelmingly just _claims_ on other people's economic activity, or "fictitious capital" in Marx-speak.

The only way environmentally-meaningful degrowth would be possible only at the expense of "the rich" is if you define "the rich" so broadly that it encompasses a huge chunk (perhaps a majority) of the developed world's population.

Perhaps one reason why the far right in particular has benefited is that Europeans sense that Greens are asking them to sacrifice on the global South's behalf, and the far right would argue that the global South (especially Africa and the Middle East) is the author of its own misfortune by failing to restrain its population growth. Plus the far right explicitly defends fossil-fuelled lifestyles, consistent with their being backed by the Russian petrostate.

(Which makes it ironic that Jem Bendell further down in the thread you screenshotted basically argues that Europe should let Russia just take what it wants, even if he dresses it up in calls for "ceasefire" and "negotiated peace".)

I’m surprised at your comment on the European Parliament elections. The far right did make some gains, but very minor ones. The centre right and centre left will again dominate the EP, with a big majority, which is contrary to much of the public narrative on this election.

The Centre does hold, at least in Europe!