At least five interesting things to start your week (#25)

Maternal mortality, "living paycheck to paycheck", media negativity, diffusion of the tech industry, and the effect of corporate tax cuts

Greetings, wonderful readers! This week’s roundup actually has nothing to do with sword-wielding rabbits, but I thought the picture was amusing, so there you go.

Anyway, this week I have a couple of podcasts for you. First, I appeared on Russ Roberts’ venerable and esteemed EconTalk podcast to talk about imperialism and national wealth. Here’s a link if you just want to listen, and here’s a video link if you’d rather watch:

And I have two episodes of Econ 102 for you this week! The first is with both Erik Torenberg and Dan Romero, in which we discuss international affairs, war, geopolitics, etc:

And in the second, Erik and I discuss Claudine Gay’s resignation at Harvard, and various issues plaguing U.S. academia:

Here are Apple Podcasts and YouTube links to Episode 25, and here are Apple Podcasts and YouTube links to Episode 26!

Whew! That was a lot of podcasts. Let’s move on to the weekly roundup. This week’s items mostly center around the theme of “negative narratives about the U.S. that aren’t as dire as we thought”.

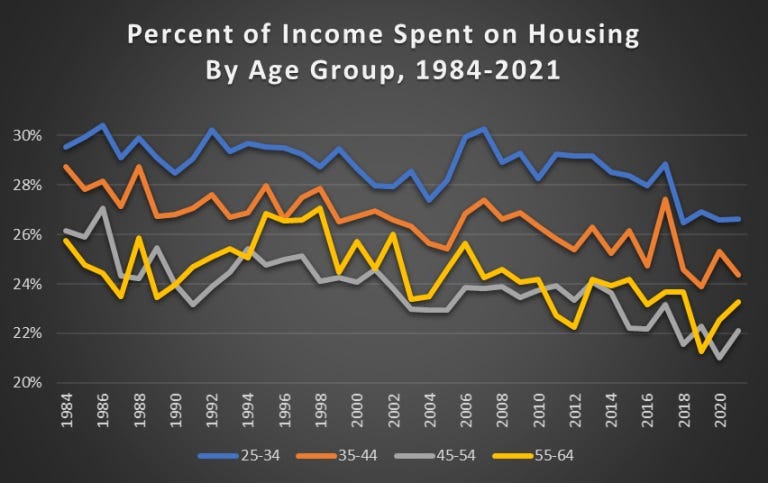

1. Maternal mortality in the U.S. is not as bad as we thought

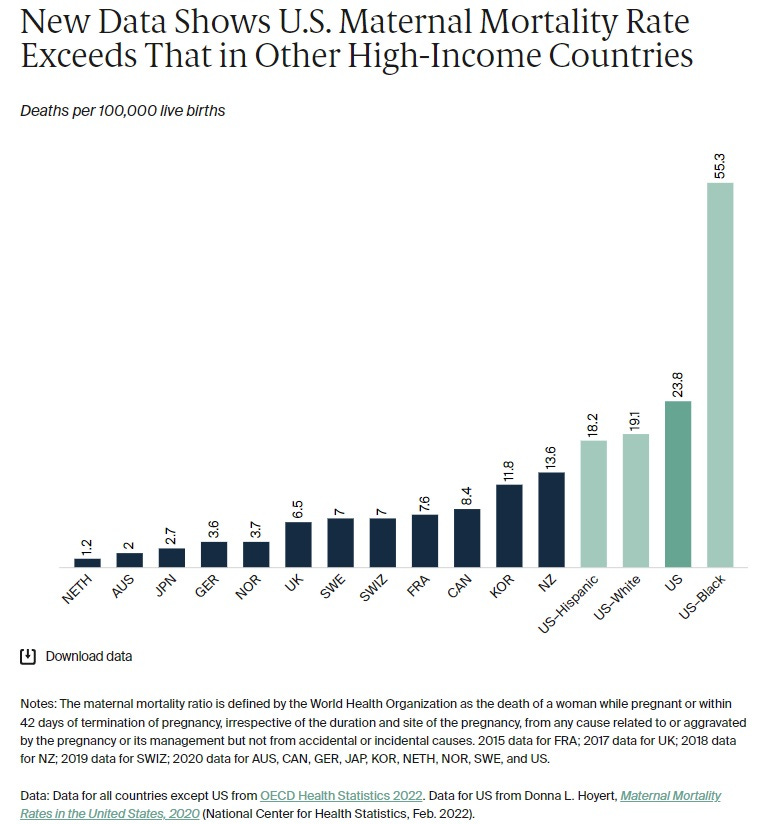

For a number of years, Americans have been freaking out about high maternal mortality rates. In my New Year’s post I used maternal mortality as a major indicator of how much better the present is relative to the past, but the U.S. has been doing a lot worse on this metric relative to other countries. Here’s a graph from the Commonwealth Fund in 2022:

And the numbers have only gotten worse in recent years.

This just added to the overall sense of the U.S. as a nation in decline. It seemed to be of a piece with our low and falling life expectancy, our overpriced health care, and so on. It was one more fact that a lot of people knew that contributed to the general sense of crisis in the late 2010s.

Only there’s one slight problem: The recent increase may not have happened at all. Starting in 2003, U.S. states started rolling out a change to death certificates — a checkbox for pregnancy at the time of death. This resulted in a whole lot more deaths getting labeled as pregnancy-related. Joseph et al. (2021) tell the story:

Rigorous studies carried out by the National Center for Health Statistics show that previously reported increases in maternal mortality rates in the United States were an artifact of changes in surveillance. The pregnancy checkbox, introduced in the revised 2003 death certificate and implemented by the states in a staggered manner, resulted in increased identification of maternal deaths and in reported maternal mortality rates. This [paper] summarizes the findings of the National Center for Health Statistics reports…[C]rude maternal mortality rates did not change significantly between 2002 and 2018, [and] age-adjusted analyses show a [21%] temporal reduction in the maternal mortality rate…Specific causes of maternal death, which were not affected by the pregnancy checkbox, such as preeclampsia, showed substantial temporal declines.

And here is a graph:

They go on to show that causes of maternal death specifically associated with pregnancy (e.g. eclampsia and amniotic fluid embolisms) have declined, even as causes of death less related to pregnancy (e.g. hypertension and diabetes) have risen. That suggests that we’re looking at a change in how maternal deaths are reported, rather than a worsening of obstetric care in the U.S.

That doesn’t let the U.S. medical system completely off the hook, though. Even before the reporting change, U.S. maternal mortality was a bit higher than most rich countries:

This isn’t quite as bad as the Commonwealth graph, but it’s not great either (and what the heck is up with South Korea??). The U.S. still has a lot of work to do to reduce maternal mortality. But like many of the declinist narratives of the 2010s, this story turns out to have been a lot less dramatic than we thought.

2. The silliest economic statistic in America strikes again

Speaking of overblown crisis narratives, how about the idea that most Americans are “living paycheck to paycheck”? You see a lot of people making this claim, including the venerable Bernie Sanders:

Now, I support the Department of Labor’s rule changes. But the hoary old chestnut that most Americans “live paycheck to paycheck” really needs to be retired. As economic statistics go, this one is the fakest of the fake.

Basically, what happens is that private companies like LendingClub go around and ask people “Are you living paycheck to paycheck?” And most people say yes. And then those numbers just get reported by the financial press as if they are some sort of economic fact. But they aren’t. Because “living paycheck to paycheck” doesn’t have a well-defined meaning.

Does “living paycheck to paycheck” mean that:

You have zero savings?

Your savings are too small for comfort?

You have zero or insufficient liquid savings — cash in the bank, as opposed to stocks in your retirement account?

You don’t build any wealth in a typical month?

You save money in your retirement account and by paying off your mortgage each month, but you don’t add to your liquid cash?

You couldn’t pay your monthly bills without your next paycheck?

You just look forward to getting a paycheck each month?

No one knows. It probably means many different things to the many different people who answer “yes”. So please stop citing the “paycheck to paycheck” number. It’s meaningless.

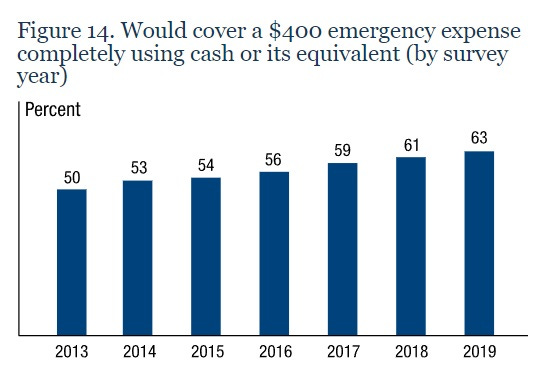

As it turns out, some economists actually do look at well-defined data on how much of a financial cushion Americans have. The 2022 Survey of Consumer Finances found that about 98.6% of American households have checking accounts or similar accounts, and the median amount of money in these accounts was $8000. In 2016, about 76% of Americans had more than $400 in the bank — an increase from the mid-2000s. And the percentage of Americans who say they would choose to cover an unexpected $400 expense by paying cash rose from 50% to 63% between 2013 and 2019:

Only 12% said they couldn’t cover the $400 expense.

Now, 12% of Americans being unable to cover a $400 expense is way higher than it should be! But it’s nowhere close to the numbers of people you see claiming to “live paycheck to paycheck”. Financial insecurity is yet another economic problem that we should absolutely take seriously, but where popular narratives of crisis and decline have just been way, way overblown.

3. News is getting increasingly negative

Why are so many negative narratives becoming conventional wisdom among the American news-watching populace? Part of it is just the general unrest of the late 2010s, I think, and part is the messaging of outsider political factions who want to profit from creating a sense that the nation is in crisis. But the news media itself has become increasingly negativistic over the past few decades.

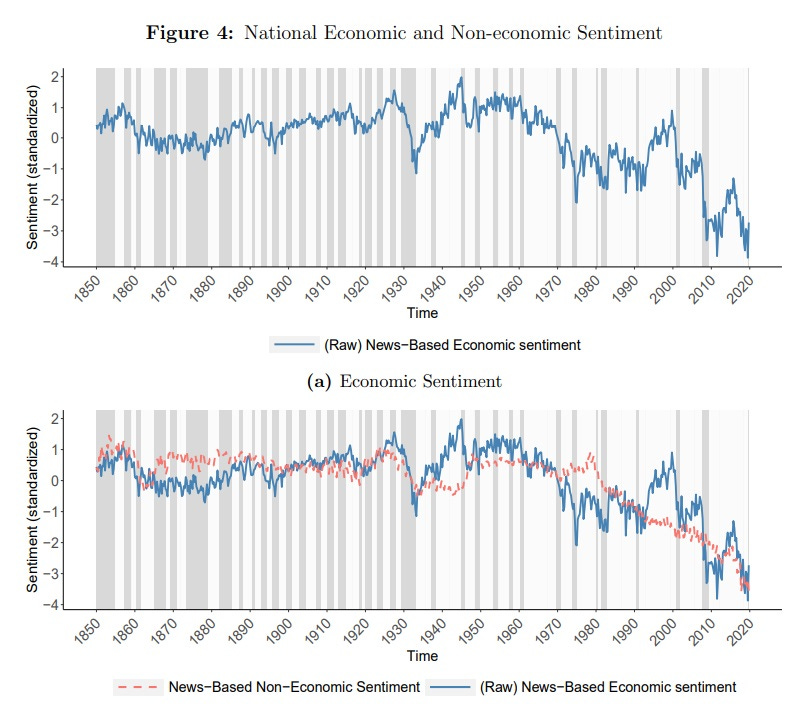

Binsbergen et al. have a new paper in which they use text mining to analyze the language used in newspapers. They construct a measure of positive vs. negative sentiment for both economic and non-economic news. In the short term, their economic sentiment measure corresponds with economic events — negative sentiment with recessions or inflation, and positive sentiment with economic booms. In the long term, however, both economic and non-economic sentiment have been on a downward trend for many years:

What’s going on here? As everyone knows, and as a ton of research shows, news suffers from negativity bias — bad news gets more attention than good news, which gives the media an incentive to emphasize and over-report the bad stuff. This tendency might have increased in recent years, as the news media got more competitive; increased competition due to deregulation and new technology might have forced newspapers to become increasingly alarmist and negativistic just in order to survive.

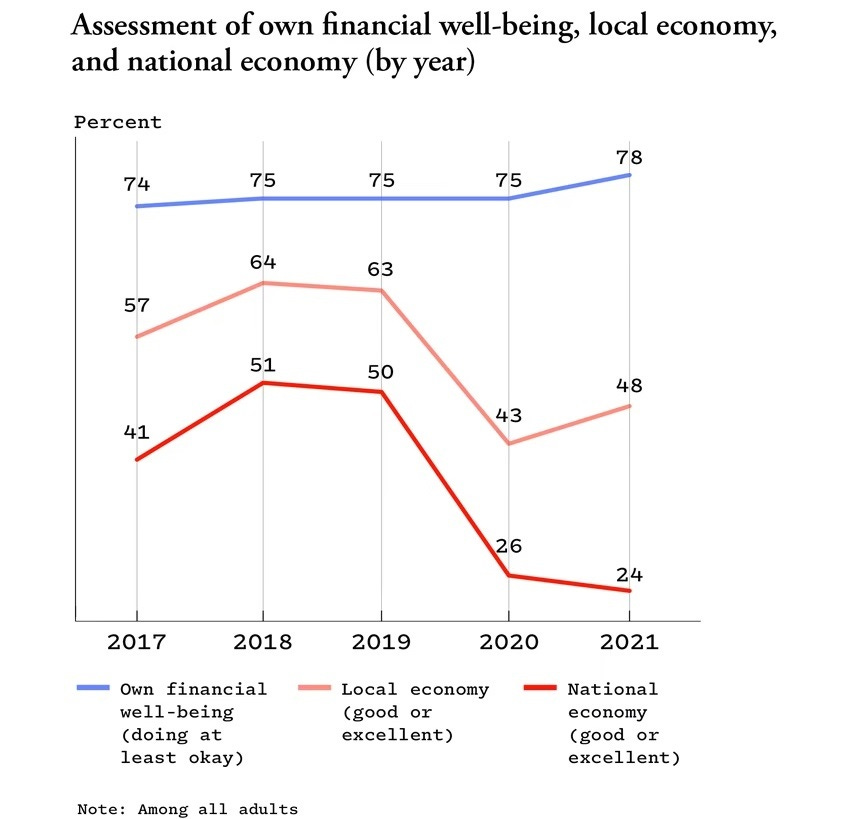

Another hypothesis I thought of is that a shift from local news to national news might have resulted in more negativity. I can’t find research on whether local news tends to be more positive than national news, but it’s certainly true that people tend to think their local economy is better than the national economy:

Perhaps the long slow death of local newspapers, and the concomitant nationalization of the news, is driving negativity? It’s worth looking into, I think.

4. Economic activity is spreading out throughout America

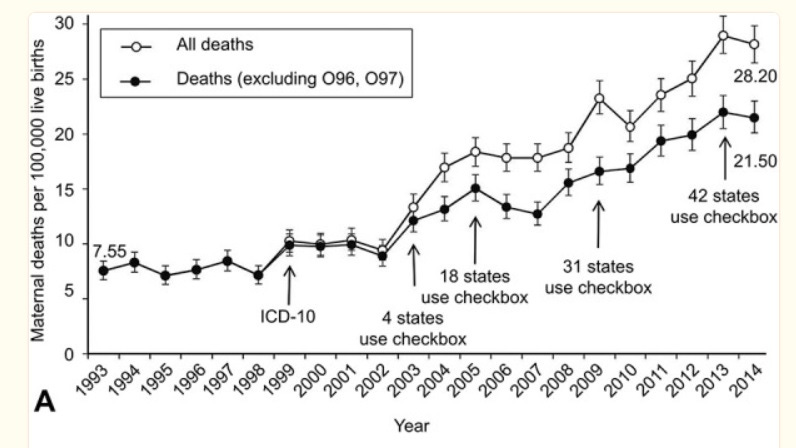

Yet another common negative narrative is that Americans are spending a lot more on housing than they used to. This isn’t true. Jeremy Horpedahl has a post in which he debunks this common myth. Using data from the Consumer Expenditure Survey, he shows that the percent of their income that Americans spend on housing overall (including owner-occupied housing) has been falling for years , while the percent they spend on shelter (i.e., rent) has remained basically flat.

But there’s a problem with this story: It’s not adjusted for where people live. Over the last quarter century, the housing and rent premium for living in “superstar” cities like San Francisco has skyrocketed, driving people with modest means out of these cities. This means that U.S. cities have become more segregated by income, with poor people shut out of the best locations by housing shortages.

But that story may now be starting to change as well. Mark Muro and Yang You of Brookings have a new report showing that the IT industry is diffusing throughout the country:

For the first time in more than a decade, digital activity seems to be spreading out. Specifically, the list of metro areas increasing their share of the nation’s tech sector…is now dominated by a group of non-superstar cities wholly different from the Big Tech meccas that ruled for years…

Between 2020 and 2022…San Francisco and San Jose disappeared from the list of metro areas gaining the highest shares of digital employment. Supplanting them have been vibrant “rising star” metro areas such as Dallas, Denver, Miami, and Salt Lake City…Rounding out recent years’ top 10 metro areas for growth in digital services employment share are relative tech newcomers such as Provo, Utah; Nashville, Tenn.; Houston; and Jacksonville, Fla.

Some of this is due to the rise of remote work and the end of the 2010s tech boom. Some is due to housing shortages in the superstar cities. But Muro and You connect a lot of it to industrial policy:

[A] welcome “big build” of private investment—some “reshored” or “localized” from abroad—broke out across the country in 2021, with promising benefits for “the rise of the rest.” Since then, the new funding surge has yielded more than $230 billion in private semiconductor and electronics manufacturing investments as well as tech and digital services spending—much of it distributed widely across the county. Many of these investments will in turn attract other regional investments in job-intensive ancillary industries such as computer systems design…Beyond the private investment boom, sizable portions of the $3.8 billion in landmark economic development legislation from the last Congress will channel billions of additional government (and also private) investment into new and “rising star” metro areas in the heartland, South, and Mountain West.

This sort of place-based industrial policy is what a lot of people were arguing for back in the 2010s, especially when Trump’s election in 2016 seemed to many to embody the rage of the Rust Belt and other forgotten places. But it was the Biden administration that finally ponied up the cash to invest in building factories in the heartland.

In any case, if the tech industry does keep spreading out throughout America, it’ll be a very good thing, even if some of it was caused by high housing costs in places like San Francisco. And it would follow the historical pattern of industries spreading out through the nation in search of cheaper land after they mature and their clustering effects become less overwhelming.

5. Corporate tax cuts aren’t as great as economists thought

Economists figured out years ago that unless tax rates are very high — as they were in the years after World War 2 — that cutting personal income taxes doesn’t actually stimulate the economy that much. This is why the Bush tax cuts of the early 00s failed to do anything for the economy, and Republicans stopped emphasizing personal income tax cuts as the main pillar of their economic strategy.

But there was still a lot of hope that corporate tax cuts were different. A classic theory in economics suggests that taxation on productive capital should be zero — since you want the economy to accumulate as much capital as it needs, you should leave it untaxed, and then tax other things like labor or consumption. That theory always had lots of assumptions and caveats; in fact, you probably should tax capital income. But the basic principle that capital is something productive that gets built up over time still suggested that we should tax it more lightly than other forms of income.

So economists and econ writers were somewhat optimistic that Donald Trump’s corporate tax cuts in 2017 — which lowered corporate tax rates to 21% — would give the economy some kind of boost. In fact, the late 2010s were very good economic years, and it wasn’t insane to suggest that Trump’s tax cuts had something to do with that.

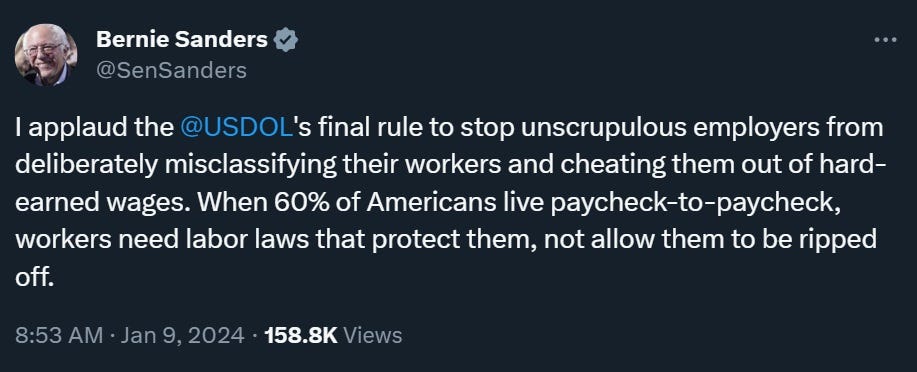

But a 2022 meta-analysis by Gechert and Heimberger suggests that corporate tax cuts aren’t actually that powerful in practice:

We apply meta-regression methods to a novel data set with 441 estimates from 42 primary studies. There is evidence for publication selectivity in favour of reporting growth-enhancing effects of corporate tax cuts. Correcting for this bias, we cannot reject the hypothesis of a zero effect of corporate taxes on growth.

And like many such meta-analyses, they have a “funnel graph” showing the estimates clustered around zero:

Note that if the authors don’t correct for publication bias, the literature finds that corporate tax cuts do boost growth, albeit by a moderate amount. It’s only once the correct for publication bias that they find no effect at all. The correction for publication bias relies on the idea that the funnel graph above should be symmetric — that a literature with no bias should have as many incorrectly high estimates as incorrectly low estimates. Basically, this is an argument that we should look at the modal estimate — the peak at 0 effect — rather than the mean.

I don’t necessarily buy that argument. It’s possible that there are methodological biases that tend to reliably produce a bunch of crappy studies right around zero, but not elsewhere. For example, maybe corporate tax cuts take years to have an effect, so that studies that try to look for the effect too soon end up clustering around zero. If that’s true, the “true” distribution of effects shouldn’t have the peak at zero, and the “uncorrected” mean of the estimates is closer to the truth.

But even if that’s the case, that effect size is still fairly modest — a growth boost of only 0.2 percentage points for a 10 percentage point corporate tax cut (which is bigger than what Trump did). And theory tells us that the growth boost won’t be permanent, since the economy will eventually reach a new steady state with a higher level of capital, after which growth depends only on technological progress.

So I think the empirical literature is just telling us that corporate tax cuts are less powerful than we had thought. That doesn’t mean they’re useless — especially for developing countries that don’t have a big capital stock yet. But overall I think there’s reason to think that the last great hope of the tax cut enthusiasts has done all it can. From now on, the U.S. should focus on other ways to boost growth.

P.S. - Here are a couple more pictures of “battle bunnies” that I made with GPT-4:

I like the WH40K bunnies! I'm sure the Emperor approves...

On tax cuts - seems self evident, tbh. The macroeconomic environment/sector-specific economic circumstances are likely to dominate tax changes so completely as to make tax changes imperceptible.

So, sure, if the economy is hot, cutting taxes might ADD to industrial investment and corporate spending as companies use the extra funds to take advantage of the supporting environment. But in a recession or tepid environment? What would YOU do, if you were a CEO? Take the tax cuts and build your cash reserves/pay down debt, to lower your leverage?

At least, when it comes to VAT and/or personal income taxes, you can hope for a counter-cyclical effect. But corporate taxes? Unlikely... And no one ever started a company because corporate taxes dropped one or two points...

You'd think a battle bunny would have some ear armor, but what do I know?

Maybe bunnies have insensitivities I don't know about. For example, horses have no feeling in their manes or tails.