At least five interesting things for your weekend (#13)

Climate messaging, antitrust, Chinese consumption, the Fed and inflation, marriage and happiness, and some Star Trek recommendations

I’m finding it difficult to maintain a strict schedule for these roundups, because interesting things arrive in my queue at varying speeds. When five or more things take less than a week to arrive, I can keep a weekly schedule, but when they take longer, I have to delay a bit. So that’s why the roundups keep coming at different times of the week.

Anyway, we begin, as always, with podcasts. There are three this week!

In the latest episode of Econ 102 with Erik Torenberg, we discuss a variety of stuff, including the future of interest rates, the fiscal cost of U.S. support for Ukraine, and the song “Rich Men North of Richmond”. Here’s a Spotify link:

And here are links to Apple Podcasts and YouTube.

Brad DeLong and I also have another episode of Hexapodia, in which we talk about economic development, and why a simple growth model from the 1950s actually predicted China’s growth arc better than more complicated theories based on political economy:

Also check out this post from Brad where he asks ChatGPT to explain our podcast’s title, and hilarity ensues.

I also appeared as a guest on the Luminary podcast with Erik Cederwall and Sachin Gandhi! We talk mostly about tech stuff. Here’s a Spotify link:

And here is a link on Apple podcasts.

Anyway, on to this week’s Five Interesting Things. There were only five, but then I decided to add Star Trek!

1. Climate scientists and public messaging

Climate scientist Patrick Brown and several co-authors recently wrote a very important paper about the impact of climate change on wildfires in California. It was published in Nature, one of the top scientific journals. Basically, when the temperature is hotter, it dries out plants more, making fires more common. The upshot:

So far, anthropogenic warming has enhanced the aggregate expected frequency of extreme daily wildfire growth by 25% (5–95 range of 14–36%), on average, relative to preindustrial conditions…When historical fires are subjected to a range of projected end-of-century conditions, the aggregate expected frequency of extreme daily wildfire growth events increases by 59% (5–95 range of 47–71%) under a low SSP1–2.6 emissions scenario[.]

A 25% increase in fire is certainly enough to worry about, but not enough to explain monster fire years like 2020. Presumably there are other factors involved. In a post over at The Free Press, Brown admits that he and his co-authors avoided mentioning some of these other factors in order to get published:

[I]n my recent Nature paper, which I authored with seven others, I focused narrowly on the influence of climate change on extreme wildfire behavior. Make no mistake: that influence is very real. But there are also other factors that can be just as or more important, such as poor forest management and the increasing number of people who start wildfires either accidentally or purposely…[Including these] would detract from the clean narrative centered on the negative impact of climate change and thus decrease the odds that the paper would pass muster with Nature’s editors and reviewers.

And Brown alleges that this sort of behavior is pervasive, because of pressure for climate scientists to stay on message:

This type of framing, with the influence of climate change unrealistically considered in isolation, is the norm for high-profile research papers. For example, in another recent influential Nature paper, scientists calculated that the two largest climate change impacts on society are deaths related to extreme heat and damage to agriculture. However, the authors never mention that climate change is not the dominant driver for either one of these impacts: heat-related deaths have been declining, and crop yields have been increasing for decades despite climate change. To acknowledge this would imply that the world has succeeded in some areas despite climate change—which, the thinking goes, would undermine the motivation for emissions reductions.

This story sounds somewhat plausible. I’ve written about scientific experts’ noble but misguided impulse to fudge their conclusions when communicating with the public, out of fear that the raw, unfiltered results would lead to policy mistakes. Scientists aren’t experts at public policy or public opinion, and so when they try to shape the messaging around their results, they often mess it up.

That said, Brown may be overstating his case here. One of the reviewers on his paper actually suggested that he and his co-authors include factors other than climate change in their assessment of wildfire risk:

The second aspect that is a concern is the use of wildfire growth as the key variable. As the authors acknowledge there are numerous factors that play a confounding role in wildfire growth that are not directly accounted for in this study (L37-51). Vegetation type (fuel), ignitions ( lightning and people), fire management activities ( direct and indirect suppression, prescribed fire, policies such as fire bans and forest closures) and fire load.

In their response, Brown et al. demur, arguing that it would be too hard to include all those other factors. They were apparently not being fully honest with the reviewer; their real concern, as Brown admitted in his post, was to avoid violating a specific narrative that they thought the editors wanted (60% of Nature papers are traditionally desk-rejected, meaning the editors never even send them out for review). But the fact that the reviewer was willing to suggest the inclusion of non-climate-change-related factors suggests that there isn’t a generally recognized code of silence about that topic.

Also, I noticed that Nature also recently published a comment by climate scientist Brian O’Neill about how many aspects of human life will improve even in the face of climate change. Some excerpts:

Large segments of the population in high-income countries believe that climate change could lead to the extinction of humankind or that, at a minimum, the future will be worse than the present. This belief is partly based on projections from climate change research; for example, hundreds of thousands of deaths from heatwaves and other climate-related causes, billions of people at risk of disease, steeply rising damages from floods, millions pushed into poverty, 20% of species going extinct, tipping points about to be bridged and parts of the world already approaching the threshold of a survivable climate. Statements in the press have echoed, and in some cases magnified, the theme. But the very same studies that underlie this dire outlook anticipate a future where, in most scenarios, humanity is better educated, better fed, longer lived and healthier, also with less poverty and less conflict, continuing trends that have been underway for decades. These improvements apply not just to the global or country average but — where such outcomes have been examined — to more vulnerable populations as well.

So the kind of message that Brown believes is taboo among climate scientists and at top journals is definitely getting out there to some extent. I found O’Neill’s comment via Brad Plumer, a climate writer at the New York Times. So the kind of balanced, positive outlook that Brown says is verboten is getting out into the mainstream media as well.

In other words, while I do think we need to worry in general about counterproductive messaging strategies on the part of scientists, I think this current fracas is more likely just a case of our climate debates being slow to catch up to new information. Brown’s concerns might have been a bigger issue back in 2010 than they are now. As of 2023, a more balanced view of the climate future has emerged, and scientists and climate writers largely seem to be perfectly willing to disseminate and talk about that balanced view.

Update: Here is a long interview with Brown, by Robinson Meyer.

2. Antitrust appears to work (at least for some industries)

During the 2010s I blogged a lot about market power and antitrust. Basically, the field of econ tasked with studying monopolies and monopsonies, called Industrial Organization or IO, hadn’t expressed much concern over rising market concentration across the U.S. economy. But then a bunch of macroeconomists and labor economists came along and shook up that cozy world by showing that increasing market power could explain many of the weird changes that had been happening to advanced economies and labor markets since the turn of the century. Those included slower growth, sluggish wages, higher market concentration, higher profits despite lower interest rates, and a number of others.

A vigorous multi-year debate ensued, with good points made by both sides, and much high-quality new research produced. But events sort of overtook the debate when Biden appointed tough antitrust crusader Lina Khan to head the Federal Trade Commission, and she started going after mergers and monopolies more aggressively.

Now there’s some new evidence showing that this was, generally speaking, the right move. A new paper by Babina et al. studies antitrust lawsuits from 1971 to 2018 and finds that they tend to increase economic activity, at least in the nontradable sector:

[W]e compare the economic outcomes of a non-tradable industry in states targeted by DOJ antitrust lawsuits to outcomes of the same industry in other states that were not targeted. We document that DOJ antitrust enforcement actions permanently increase employment by 5.4% and business formation by 4.1%. Using an event-study design, we find (1) a sharp increase in payroll that exceeds the increase in employment, meaning that DOJ antitrust enforcement increases average wages, (2) an economically smaller increase in sales that is statistically insignificant, and (3) a precise increase in the labor share…[T]he increase in production inputs (employment), together with a proportionally smaller increase in sales, strongly suggests that these DOJ antitrust enforcement actions increase the quantity of output and simultaneously decrease the price of output. Our results show that government antitrust enforcement leads to persistently higher levels of economic activity in targeted industries.

This really bolsters the arguments of the macro and labor economists who were sounding the alarm in the 2010s. In theory, powerful companies restrict output as a way of pumping up prices, and restrict hiring as a way of pushing down wages. Babina et al.’s findings support that theory, and strengthen the case for Lina Khan-style antitrust, at least for companies that sell mostly within America. For tradable industries it might be different, since the competition they face is often mostly foreign.

But as a cautionary note, this doesn’t mean that every bad effect that people attribute to powerful companies is real. For example, many economists have studied the impact of Wal-Mart on local economies, and a new literature review by Volpe and Boland shows that the impacts they found are generally benign or positive. So antitrust action should still pay attention to the evidence in each specific case.

3. The China consumption debate

I have been asked to weigh in on the debate between Tyler Cowen, Michael Pettis, and others on the question of Chinese consumption. Basically, Pettis says that Chinese household consumption is too low, and that it has to increase in order to make Chinese growth more balanced and sustainable — an argument that a number of Chinese leaders themselves have made, as well as other economists like Paul Krugman. So weigh in I shall.

Basically, China has two main problems — the short-term crisis and the long-term slowdown. These are related, because both involve China’s massive real estate investment binge in the 2010s. When people talk about “investment” in China, at least with regards to the 2010s, they mostly mean “investment in infrastructure and real estate”. A shift toward real estate and infrastructure investment hurt China’s long-term productivity growth — perhaps partly because some of the investments were poorly chosen and inefficient, but mostly just because these are industries where productivity tends to grow very slowly. If you shift your economy toward, say, basket-weaving, it only matters a little bit how good the baskets are.

Anyway, the over-reliance on real estate also caused China’s short-term economic crisis because it created A) a housing price bubble, and B) a massive tangle of debts that will be hard to untangle without sapping economic confidence and destroying many financial companies’ business models.

How could increasing consumption help that situation? Two ways. First, fiscal stimulus — which works by boosting consumption — could help get China through the acute crisis without unemployment rising to dangerous levels. Second, China’s service industries and domestic-focused manufacturing industries may be under-resourced due to government industrial policies that favored exports in the 2000s and real estate/infrastructure in the 2010s. A removal of government policies that favor real estate and infrastructure investment might lead to more resources getting devoted to productivity improvements in more consumption-oriented industries, which could raise long-term productivity growth.

Now, these are not the same arguments that Michael Pettis and like-minded folks tend to make. They tend to think in terms of sectoral balances — investment, consumption, exports, etc. as the key quantities, without as much focus on the underlying details of the industries involved, or on prices, or on “structural” quantities like productivity. I don’t really think in that framework, so instead of trying to translate from sectoral balances to standard econ language, I prefer to just observe that my own policy recommendations for the Chinese government would be similar to those that Pettis endorses.

I also agree with Tyler, however, that “more consumption” is too simplistic a prescription, and agree with his more accurate framing:

It is plausible to argue that China has inefficiency wedges that favor some kinds of investment over consumption, such as massive subsidies for infrastructure construction. But it is odd to conclude that China needs outright “more consumption,” which indeed will limit China’s prospects for the future. What China needs is “both more consumption and more investment in the discouraged sectors.” That would both boost growth and the welfare of Chinese citizens…You might…help growth rates if you could free up or otherwise assist China’s numerous dysfunctional sectors, again with health care being one very obvious example.

I think “consumption” here is being used as a shorthand for “industries Xi Jinping considered unimportant and directed resources away from”, including health care. So I think Tyler would agree with Pettis et al.’s recommendation of redirecting resources (or allowing resources to be redirected; with China it’s hard to tell the difference) toward neglected sectors, most of which are domestic-focused consumer industries.

The real policy disagreement between Tyler and Pettis et al. is about whether mailing checks to Chinese consumers would help. Tyler writes: “Don’t expect to get far by printing up lots of money, giving it to Chinese consumers, and telling them to spend it.” I think Tyler is probably wrong, and that this would help China, for two reasons. First, despite having interest rates above zero, China does seem to have high cyclical unemployment, implying a lack of demand that looser monetary and fiscal policy could help fill; the country may effectively be in a liquidity trap due to features of the state-controlled banking system, even though rates are at over 3%. Second, handing cash to consumers would probably shift economic activity toward the kinds of industries Xi Jinping has hitherto starved of resources, helping to remove the “inefficiency wedges” that Tyler talks about.

But also, the stimulus debate is probably a bit academic, at least for now, since Xi and the CCP appear pretty dead-set against large-scale stimulus. It’ll probably be hard enough convincing them just to bail out the country’s banks and local governments.

4. The Fed should get some of the credit for taming inflation

Now that inflation is coming down, there’s a big debate over who gets the credit. Back in July I gave mainstream macro a high grade on how it handled this inflationary episode, for the simple reason that rate hikes seem to have done their job well. If you do what the textbook says to do, and you get good results, I say the textbook did well.

A lot of people in the “heterodox” sphere got mad at this, arguing that mainstream macro failed because it incorrectly predicted that unemployment would have to rise in order for inflation to fall. This conveniently ignores that the heterodox people themselves predicted much the same thing; back when the Fed was hiking rapidly, they were all shouting about how dangerous this was and how much unemployment it would create. Heterodox people seemed to believe in the Phillips Curve just as much as mainstream people; they just disagreed on whether the tradeoff was worth it.

But mainstream macro’s critics are also making a mistake about what mainstream macro actually predicted. Yes, some prominent “mainstream” commentators like Larry Summers and Olivier Blanchard predicted (as did the heterodox folks) that unemployment would rise as a result of rate hikes. But many actual mainstream macroeconomic theories allow for “immaculate” disinflation without a rise in unemployment. This can happen if expectational effects are very strong — i.e., if rate hikes convince the country that the Fed is hawkish, and businesses just sort of give up and stop raising prices.

A new paper by Stefania D’Amico and Thomas King of the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago argues that it was exactly this sort of expectational effect that allowed rate hikes to bring inflation down so easily and so fast. They write:

[W]e use the model from D’Amico and King (2023), which explicitly incorporates economic expectations and allows for forward guidance. That model implies larger effects of monetary policy and faster policy transmission than other empirical models…According to the model’s forecast, the policy tightening that’s already been done is sufficient to bring inflation back near the Fed’s target by the middle of 2024 while avoiding a recession.

[Our] model explicitly accounts for measures of expectations and for shocks to the current and expected policy rate; hence, it is better equipped…to capture the “expectations channel” of monetary policy, which results in larger and faster estimated effects on the economy.

Now, this model is no more definitive than any of the other macro models that rely on different assumptions. But it does use actual survey measures of expectations instead of simply making assumptions about how expectations work, and I like that. So I’m inclined to give some weight to this paper, simply because it treats expectations as a real, tangible thing that you can actually go out and measure.

So the upshot here is that the Fed does deserve some of the credit for bringing down inflation — that it wasn’t just a result of low oil prices or the “long transitory” unwinding of post-pandemic supply chain snarls (though those certainly helped). And yes, mainstream macro does deserve a good grade for how it handled this episode.

5. Will marriage make you happier?

I would like to direct your attention to this excellent article in The Atlantic by Olga Khazan, about whether marriage makes people happier. It provides a good opportunity to teach about correlation vs. causation.

The article starts off by citing a recent paper by Sam Peltzman, which finds a very strong correlation between marriage and happiness in the U.S. This is hardly a new result — Khazan lists a number of other papers that have all found the same correlation. Peltzman’s new contribution is to use the decline in marriage to explain the decline in overall reported happiness in America.

Anyway, if this was the only part of the article you read, or if you only read some tweets about the article instead of clicking on it, you might be tempted to say “Aha! This is just correlation, not causation! What’s actually happening is that happier people are more likely to get married in the first place!” And then, satisfied that you are smarter than some stupid journalist, you click on to the next thing.

Except Khazan is very much not a stupid journalist; she is extremely smart, and she would not write an article like this without considering the question of correlation vs. causation. If you assumed she neglected this question, the fault lies entirely with you for not reading the full article. Khazan writes:

Peltzman didn’t explore why married people are happier, but other researchers have, and they fall into two competing camps. Camp No. 1, that of cynical libertines like me, believes that marriage doesn’t make you happy; rather, happy people get married. One 15-year study of more than 24,000 Germans, for instance, found that those who got married and stayed married were happier than the unmarried ones to begin with, and any happiness boost they got from the marriage was short-lived…

In Camp No. 2 are the romantics, who believe that getting married makes you happy, because there’s something special about marriage. In a research brief for the conservative Institute for Family Studies, the research fellow Lyman Stone crunched the GSS data again and found that getting married does boost happiness, for at least two years after the wedding, and it does so even when you control for the person’s previous level of happiness…

Perhaps the strongest evidence for this camp’s thinking comes from a 2017 study of thousands of British people that found that those who got married were more satisfied with their life than those who didn’t, even when you control for how satisfied they were before they got married. It also found that the married Brits were more satisfied years later (meaning the happiness boost wasn’t fleeting), and that marriage inoculated the couples somewhat from the midlife dip in happiness that most people experience.

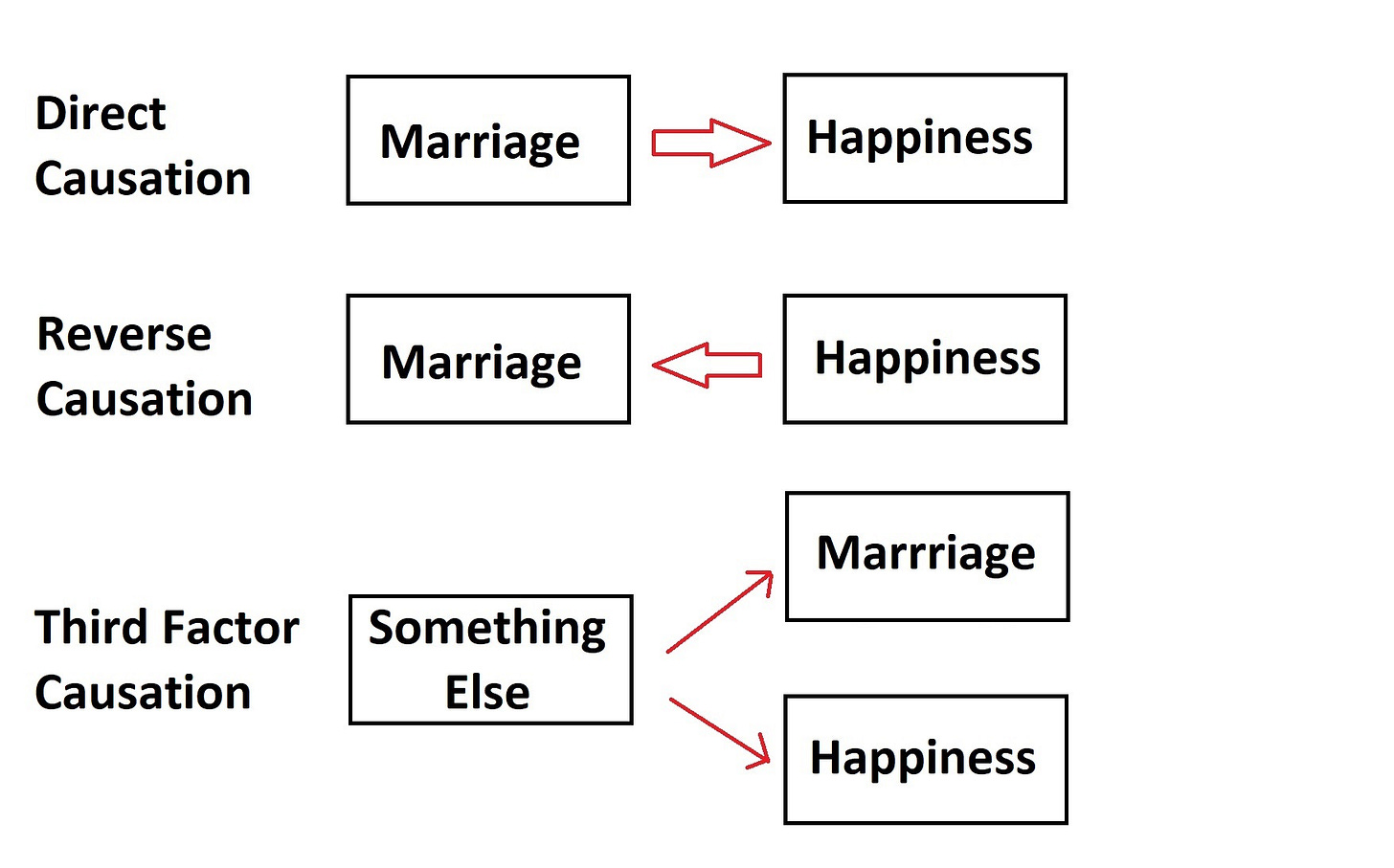

So, there’s evidence on both sides of the debate here. But what none of these studies can control for is the possible presence of some unobserved third thing that causes both marriage and happiness. Here’s a little illustration of what I mean:

No matter how many controls you include, you can’t rule out the possibility that there’s some other third thing out there that makes people get married and makes them happier. Maybe some sort of social support from family and friends, or maybe something genetic. Who knows!

But this illustrates why we need a natural experiment. To really isolate the causal relationship between marriage and happiness, we need some sort of random change in policy or social or economic conditions etc. that pushes some people to get married when they otherwise wouldn’t have, or not to get married when they otherwise would have. That wouldn’t entirely answer the question, because there could still be different effects on different people or at different times, etc. But it would certainly be a lot clearer of an answer than the studies we have now. Unfortunately, I can’t find a natural experiment like this, but maybe one exists.

Anyway, this is one of the many reasons why social science is so tough.

6. Star Trek is great again

I’ve been a lifelong devoted Star Trek fan. But after the turn of the century, I noticed a marked decline in how much I liked what the franchise was putting out there. I thought Enterprise was stilted and poorly made. I thought the J.J. Abrams movies were decent, but too action-oriented and a bit of a retread. I thought Discovery was an interesting and ambitious failure — an attempt to take Star Trek in completely new thematic and narrative directions that ultimately couldn’t find any new directions that worked. And I thought the first two seasons of Picard, while watchable, felt more like an extended Patrick Stewart dream sequence than anything else. I had resigned myself to the idea that Star Trek, like so many other entertainment franchises, had just lost the magic that once made it special. Ironically, the show that did the best job of capturing that magic, though in a slightly more amateurish fashion, was The Orville, which had originally been intended as a Trek parody.

Then, suddenly, Star Trek got good again. And not just good, but amazing — better, in some ways, than it ever was before. First there was the cartoon series Star Trek: Lower Decks, which is a parody series along the lines of what we thought The Orville was going to be. It’s the kind of show I wouldn’t expect to be funny, but I was pleasantly surprised. It definitely has a Rick & Morty flavor to it, which isn’t surprising, because the creator was a writer and producer for Rick & Morty.

The third and final season of Picard, meanwhile, is simply incredible. It does for Star Trek: The Next Generation what the original movies did for the original series in the 70s and 80s, and which the TNG moves never quite managed to do in the 2000s. It’s even more gripping and cinematic than the J.J. Abrams movies or Discovery, but those action sequences alternate with emotional and tender moments that the franchise hasn’t managed to nail for decades. Yes, it’s a nostalgia trip, but it isn’t just a nostalgia trip, because the fact that these characters are now old is a fundamental part of the show. (Without giving too many spoilers, there’s even a fun part near the end when they fact that they’re all old becomes very useful.) Most importantly, the ending of Picard is absolutely picture-perfect in every detail, which makes Star Trek: The Next Generation one of the few TV shows that has ever had two perfect endings.

But the best thing about the new era of Star Trek is Strange New Worlds. For those who don’t know, this series is spinoff of Discovery and a prequel to the original series — it takes place on the original Enterprise of Kirk and Spock fame, five years before Kirk takes the captain’s chair. It features Spock and Uhura from the original series crew, as well as bigger roles for a bunch of characters who had bit parts on the original show — Captain Pike, Nurse Chapel, Dr. M’Benga, and Una Chin-Riley (“Number One”). There are also a couple of new characters, and occasional guest appearances by Kirk and the rest of the original series crew.

And this show is amazing.

Most reviewers talk about how the series is a return to the basic Star Trek pattern — themes of optimism and exploration, a highly competent crew who are all basically good people and who tend to make reasonable judgement calls under pressure, an episodic story structure, and Klingons who don’t look like weird lizard-creatures. And that is all true. But SNW is not a nostalgia trip in any way — it’s more like a modern update on the original series concept, similar to what TNG did. It leverages the skill of modern “prestige TV writers” to insert emotional drama into the Star Trek framework without the lazy expedients of making the characters do stupid stuff or act like jerks. The bridge crew represent the best of humanity; they sob in their rooms, tell each other small lies, and have awkward romances, while still being hyper-competent at their jobs. The structure is episodic, but the “space monster of the week” plots are just a wrapper around a whole lot of slow-burning character-focused story arcs.

Instead of being yet another Game of Thrones wannabe, in other words, Strange New Worlds represents an evolution beyond the now-familiar 2010s format — a blend of episodic and long-term stories that feels like something fundamentally new. And that blend also allows SNW to constantly experiment — there’s one episode that’s a musical (don’t worry, it’s good), and one that’s a semi-cartoon crossover with Lower Decks. I can’t remember a time when I was this excited to see a TV show every week, and a large part of that is that I don’t know what to expect.

It also has one of the best opening sequences of any Star Trek show ever, if not the best.

Strange New Worlds is simply the best new Star Trek show since Deep Space Nine, and it’s among the best things you can watch on TV right now. Audiences are realizing it too, as the show gains in popularity. When people point at this show and say “Star Trek is back”, they aren’t kidding. The writers’ and actors’ strikes will interrupt the regular release of SNW seasons (Note to studios: Just pay the damn writers and actors, please!), but in the meantime there are 20 episodes to watch, so check them out.

Gay marriage legalization as a natural experiment?

As someone who’s seen almost every episode of every Star Trek series, I enjoy Lower Decks even more than SNW. But I can admit that Strange New Worlds is probably a better show for most people.