At least five interesting things to start your week (#37)

The U.S. as trade war leader; Russia/China infowar; Biden and inflation; Yglesias on industrial policy; How to get immigrants to the Rust Belt; How to lose money

Howdy, folks! I’m all done with jury duty and conferences and things like that for the moment, so that gives me a little more time to write!

I have two episodes of Econ 102 for you this week, and they’re both about Joe Biden. In the first, Erik and I talk about Biden’s new tax plan:

And in the second, I make the general case for Biden’s reelection.

Remember, if you want to ask me some questions for the Econ 102 podcast, just email the producers at Econ102@turpentine.co!

And here’s a fun episode of Hexapodia where I challenge Brad on his support for engagement with China back in the 2000s:

Anyway, on to this week’s list of interesting things! Some weeks I use the roundup to cover a bunch of things I didn’t mention in my longer posts. But this week I’m using the roundup as an opportunity to hit on some of my standard hobbyhorses — competition with China and Russia, inflation, industrial policy, and immigration.

1. Why much of the world will follow the U.S. on tariffs

In economics, there’s an old theory called the Stackelberg competition game. Instead of companies all trying to set their prices at the same time, there’s one important company that sets the pace for the rest. The game has basically become a mental stand-in for any situation where there are one or more first movers and one or more followers. Some people have used Stackelberg-type models to analyze international trade policy, while a few have even applied the idea to U.S.-China competition.

I suspect that at some point, someone will write a Stackelberg-type paper about the trade war that’s now shaping up around the world. In general, China was the “leader” in this game, since it was China’s giant flood of manufactured exports that prompted other countries to consider protectionist responses. But in terms of tariffs, the U.S. appears to have played an important role as the first mover:

Deese was one of Biden’s most important economic advisors, so it’s very likely that the idea that other countries would follow suit played a role in the administration’s thinking when it decided to roll out huge, eye-catching tariffs.

So is Deese right? Is the world following the U.S. here? Politically, I’d say the answer is “no”. The EU was moving toward imposing tariffs on Chinese EVs long before Biden’s announcement. Brazil was already ramping up tariffs on Chinese cars, and on other products as well. Thailand too. None of these countries needed U.S. “permission” to protect their domestic businesses.

But economically, I think there’s a case to be made that the world will be pressured to follow America’s lead here. Although there are various possible reasons for China’s export surge, one thing that definitely seems true is that Chinese production, at least for now, is being determined by internal incentives rather than by anything that happens overseas. Which means that if tariffs block Chinese EVs and other goods from entering the U.S., Chinese companies won’t simply shut down their production lines. They’ll keep production rolling, and try to sell the goods somewhere else — to India, to the EU, to Southeast Asia, to Latin America, etc.

In other words, the U.S. tariffs are going to make the Second China Shock more severe for everybody else. And that will increase the pressure for everyone else to respond by mirroring the U.S. tariffs. As more and more countries increase tariffs, the flood of Chinese goods will be compressed into a smaller and smaller set of destination countries. Eventually, even the most reluctant protectionists will be facing such a huge wave of low-priced imports that their local businesses will howl at the government to respond.

India and the EU are already very vocally worried about this. They are probably not quite as inclined to resort to swift, dramatic protectionist measures as the U.S. was. But the pressure on their domestic manufacturing sectors is now higher than it was for the U.S. And so it may go, around the world, one after another. The U.S. may or may not have exerted political leadership on tariffs, but it was probably the first domino in a chain.

2. China and Russia want to rule your information space

While we’re on the topic of international competition, let’s talk about the information war.

Rest of World recently published a great article on TikTok’s Chinese connections. A few excerpts:

[M]ore than a dozen current and former U.S.-based TikTok employees who spoke to Rest of World, most of whom requested anonymity for fear of retaliation from the company, say that TikTok’s ties to ByteDance go further than what the company presents. They say ByteDance executives, and not [CEO Shou Zi] Chew, manage key departments made up of thousands of U.S.-based TikTok employees…

Internally, employees and managers call the company “ByteDance” and “TikTok” interchangeably, as most tech teams work closely with China-based Douyin staffers. A senior TikTok engineer told Rest of World he estimates that the tech teams, which include software engineers, product managers, and user experience designers, have 40% to 60% of their members based in China.

There’s little doubt at this point that TikTok is censoring Americans’ videos on topics it doesn’t like, as well as providing lots of personal data on Americans (and Canadians, and everyone else) to the Chinese government. Canada’s intelligence agency recently warned citizens not to use TikTok due to privacy concerns.

Meanwhile, TikTok is far from China’s only vector of information warfare. The country has flooded American social media with bots and human-operated accounts attempting to spread disinformation and divisive messaging:

Over the past 24 months, the campaign has switched from pushing predominately pro-China content to more aggressively targeting US politics…Part of a wider multibillion-dollar influence campaign by the Chinese government, the campaign has used millions of accounts on dozens of internet platforms ranging from X and YouTube to more fringe platforms like Gab, where the campaign has been trying to push pro-China content. It’s also been among the first to adopt cutting-edge techniques such as AI-generated profile pictures…Over the past five years, the researchers who have been tracking the campaign have watched as it attempted to change tactics, using video, automated voiceovers, and most recently the adoption of AI to create profile images and content designed to inflame existing divisions.

So far, their efforts have been clumsy, scattershot, and ineffective. But they may eventually learn what works and what doesn’t.

And China also has access to more traditional proxies. There’s a great report from the Network Contagion Research Institute on the network of influencers run by the CCP-connected American businessman Neville Roy Singham. This network was responsible for organizing some of the most extreme of the Palestine protests.

Meanwhile, China is probably stepping up its cooperation with Russia in the information warfare space. At a recent summit in Beijing, Putin and Xi agreed to have their news agencies coordinate more closely. Russia lacks China’s raw resources, but it has been at this game much longer, and understands the division in American society much better.

This information warfare presents a severe challenge to the way the U.S. in particular has approached media and free speech. For decades, the U.S. has effectively adopted the Nozickian libertarian idea that the U.S. government is an all-powerful sovereign that must restrain itself completely in the information space; meanwhile, this perspective holds that foreign governments are tiny atomized actors on a part with American individuals, and must therefore be free of any interference.

That approach might have made sense in the days of U.S. hyperpower, and even Soviet propaganda efforts probably didn’t strain the system too much. But with the advent of social media, and of a massive centrally-directed propaganda effort against the U.S. by a foreign government with more economic resources than our own, the Nozickian libertarian perspective on media regulation looks increasingly untenable and self-defeating. This is liberalism’s big test.

3. It’s the inflation, stupid!

Joe Biden’s poll numbers are still doing badly despite a strong economy and a generally successful presidency. And poll after poll reveals the reason for Biden’s poor performance: inflation. Here’s the Financial Times:

Joe Biden’s re-election prospects are being dogged by persistent fears over inflation, with 80 per cent of voters saying high prices are one of their biggest financial challenges, according to a new poll for the Financial Times…The findings…come amid signs in recent months that inflation is rising again despite falling steadily last year. They reverse recent gains the US president had made among the electorate about his handling of the US economy.

And here’s ABC:

U.S. adults trust former President Donald Trump over President Joe Biden on the issue of inflation by a double-digit margin, according to a new ABC News/Ipsos poll this month, which found that price increases remain a top concern for voters…In all, 85% of poll participants said inflation is an important issue, making it the second-highest priority among adults surveyed. The top priority, the economy, also relates to individuals' perceptions of price increases…On each of those issues, the economy and inflation, adults surveyed by ABC News/Ipsos said they trusted Trump over Biden by a margin of 14 percentage points.

Inflation is still way down from where it was in 2021-22. But it re-accelerated a little bit in the early months of this year, which probably gave people quite a scare. Here’s a good picture:

People are still understandably panicky after the experience of 2021-22. But the more recent surge was not just a temporary bump — underlying inflation is running at around 3.5%, which is considerably more than the rates that prevailed before Covid.

No one really knows what causes inflation, but at this point we know that it isn’t oil (which has come back down), it isn’t pandemic supply chain disruptions (which are long gone), and it isn’t pent-up savings from the pandemic (which have all been spent down already). It’s not Houthi attack on Red Sea shipping, either, since U.S. inflation is entirely concentrated in service prices like rent rather than in physical goods. The most plausible culprit is high deficit spending in the U.S. — what some progressives call “Big Fiscal”.

This puts Biden in a bind. It’s too late to cut deficits to bring inflation down before the election — even if Biden passed an austerity budget tomorrow, it would just hurt the economy in the short term and not reduce inflation until well after November. So instead, the only way the President can offer Americans relief is to throw money at them:

In the long run, this will only make the problem worse. Subsidizing housing without increasing supply raises rent. This is part of Biden’s unfortunate pattern of subsidizing overpriced service industries without raising supply, except in this case it doesn’t even create any jobs — it just flows through to landlords.

But in the short term, there’s probably nothing else Biden can do before the election to help voters feel like their lives are a little cheaper. That’s unfortunate.

4. Matt Yglesias’ two principles of industrial policy

Matt Yglesias had a great (paywalled) post on industrial policy the other day:

It’s a “grab bag” post (much like this one), so I wanted to extract a couple of highlights to make sure they don’t go unnoticed. In particular, I think he has two good insights about industrial policy that should serve as guiding principles for U.S. politicians.

First, industrial policy isn’t only about protectionism. In fact, industrial policy gets better when we maximize trade with our allies and friends;

Any policy of intensified strategic competition with China needs to be premised on closer relationships with Japan, Korea, Australia, and other Asian allies, not on treating them as enemies.

This is very important, not just because of geostrategic concerns, but because of economic ones. One reason China is such a massive manufacturing beast is that they have a gigantic unified domestic market. The U.S., being 1/4 the size of China, can’t hope to match that internal market. Neither can Japan or other smaller countries. And neither can India, which has more people than China but is much poorer.

The only way that non-China countries can get a market size to rival China’s is by combining their markets. We need to have the U.S., Europe, Japan, Korea, and India lower barriers to trade and investment between each other, even as they raise barriers to Chinese exports. Only that large combined market will give manufacturing companies an economy of scale that can rival China’s.

Matt’s other good point is that the target of industrial policy should be production rather than manufacturing jobs:

If we want domestic chip production, that’s worth spending money on, yes, but it’s also worth doing regulatory favors to the industry. That means facilitating immigration of the workers the industry wants, cutting them a break on environmental regulation, and most of all, promoting maximum productivity and efficiency rather than prioritizing “job creation” and “good jobs.”

This is absolutely right. Industrial policy will create lots of jobs, but mostly not on assembly lines. Those will have to be automated in order for the U.S. to compete with China, which is automating its own assembly lines at breakneck speed. Instead, industrial policy will create good jobs through the magic of local multipliers — the money that automated manufacturing brings in will be redistributed throughout local areas and local service industries.

A good industrial policy should therefore focus on automated manufacturing, not on providing make-work on inefficient 1940s-style assembly lines.

5. A really good idea on immigration

I’m very pro-immigration, and I think high-skilled immigration is the most important kind. But I recognize that amid all the hyperpartisan shouting and scare-mongering, there are important and real challenges to be overcome when bringing large numbers of skilled workers into our country.

The biggest is the housing problem — when a bunch of high-earning workers flood into already expensive coastal cities like San Francisco and L.A., it exacerbates the NIMBY-driven housing crunch in those areas. Yes, we should build more housing and overcome the NIMBYs, but that’s much easier said than done — skilled immigration to superstar coastal metros makes YIMBY politics into a bit of a treadmill. Meanwhile, Rust Belt areas that could benefit the most from skilled immigration often languish, because immigrants don’t move there.

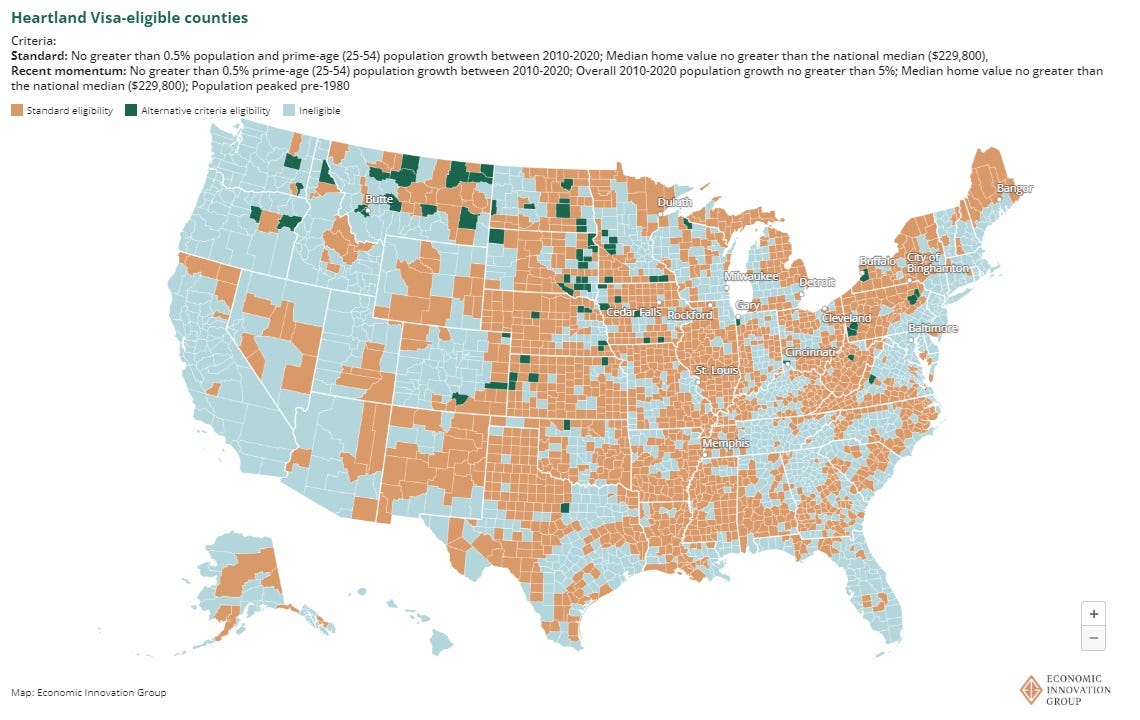

One way to solve this is to help direct immigrants to areas other than San Francisco and Los Angeles. Canada does this by allowing provinces to sponsor immigrants like employers do. The U.S. should do something along these lines. And the Economic Innovation Group, one of my favorite policy think tanks, has a proposal for how we could send skilled immigrants to Rust Belt areas where they’re needed most. They call it the Heartland Visa:

The Heartland Visa is an innovative proposal that gives communities the choice to opt-in to a new immigration pathway for highly skilled workers, entrepreneurs, and innovators. Prioritizing higher-earning applicants and those with local ties, the Heartland Visa would serve as a key component of economic revitalization in participating places.

In exchange for living in a Heartland Visa community, workers with sufficient earnings will gain permanent residency, cutting through burdensome red tape and bureaucracy embedded in the status quo immigration system. Building on our 2019 concept paper, this report details how we can make Heartland Visas a reality on the ground.

Key Features of a Heartland Visa

Dual opt-in: Counties experiencing economic decline or stagnation can decide to opt in or out of the program, while applicants select their own destinations.

Prioritize applicants with high-wage job offers: Applicants are allocated quarterly to those with the highest job offers or earnings histories, adjusted for age and local ties.

Pathway to permanent residency: Heartland Visa holders, in exchange for living in a participating community for six years, should have an expedited path to a green card.

Scale: Heartland Visas should be large enough to fundamentally change the economic trajectory of participating communities for the better.

And here’s a picture of the areas that would be eligible for Heartland Visas:

This is a great idea, and we should adopt it as soon as we can. Declining regions in the U.S. can greatly benefit from having talented workers. Their high salaries mean that they will be a huge fiscal boon to struggling cities and states. And these workers’ presence will lure corporate investment, boosting local tax revenues and causing positive multiplier effects throughout local economies.

6. An easy way to lose your money

Although I talk about financial issues a fair amount on this blog, I strenuously avoid giving specific financial advice about what assets you should buy. But not everyone is so scrupulous. Tons of financial gurus out there are extremely eager to tell you which stocks you should pick, which crypto coins you should grab, how to time the market, and so on. And most of them end up losing money for their faithful followers.

That’s the conclusion of a new paper by Kakhbod et al. (hat tip to Kyla Scanlon for the find). The paper, entitled “Finfluencers”, scans a bunch of tweets from StockTwits, and finds that the advice these influencers offer to the public tends to be quite bad:

This paper assesses the quality of investment advice provided by different finfluencers. Using tweet-level data from StockTwits on over 29,000 finfluencers, we classify each finfluencer into three major groups: Skilled, unskilled, and antiskilled, defined as those with negative skill. We find that 28% of finfluencers provide valuable investment advice that leads to monthly abnormal returns of 2.6% on average, while 16% of them are unskilled. The majority of finfluencers, 56%, are antiskilled and following their investment advice yields monthly abnormal returns of -2.3%. Surprisingly, unskilled and antiskilled finfluencers have more followers, more activity, and more influence on retail trading than skilled finfluencers.

In other words, the more attention a “finfluencer” gets, the worse advice they tend to give. There are a minority of smart advice-givers out there, but regular folks are very bad at picking which ones they are.

If you think about it, this just flows directly from the Efficient Markets Hypothesis — which, though not formally true, is a great heuristic guide for investors to think about why it’s hard to beat the market. The key question to ask yourself is: If you’re not smart enough to pick your own stocks, what makes you smart enough to pick a financial guru to pick your stocks for you? And if gurus have to allocate their scarce personal resources of time, thought, and attention to either A) picking good stocks, or B) shilling for attention, it stands to reason that the ones who specialize in the latter will be less good at the former.

Anyway, no matter what you invest in, you should always think twice before deciding you can beat the market. That’s true whether you pick your own assets or get your ideas from some influencer on Twitter.

I realize you believe Joe Biden is having a successful Presidency however I do not share your perspective. Here are my points. Good people can disagree.

1) He said he would be a transitional President and return things to normal. We all knew Biden as center-left for most of his career. , not a Progressive. Most of the antipathy towards him is that he lied to us about what he was going to do.

2) His dithering over Ukraine's armament, along with his inane comment regarding a small incursion, blundered Russia into an invasion.

3) He did not need to increase the Federal Government budget by 50%. The Inflation Reduction Act was neither inflation-reduction nor budgetary responsible.

4) His border policy not only imperials US security but has put such strains on the social compact that a majority of Americans now support mass deportations. It is overwhelming public schools and social services, and he may lose his presidency.

5) His climate change policies are ill-conceived and lack a cost-benefit analysis worth a bucket of spit. You cannot make a market that is not there. In fact, his EV strategy may end up putting US Automakers out of business. Having spent 35 years in Automotive Marketing, I can firmly tell you that US Automakers cannot make a $25,000 EV sedan and remain profitable.

6) It is clear that Americans do not want their daughters competing against men, no matter if they call themselves girls. We, Dads who went to after-school sports to support our daughters think this is nuts.

7) He can actually thank the 10 GOP Senators who approached him about doing an Infrastructure Bill. He didn’t initiate that legislation and I wish Democrats would stop writing history.

8) His reactionary posture to China and American jobs caused him to oppose Nippon Steel’s purchase of US Steel. A shell of its former self. Japan is our ally....Stupid.

Anyway, there are probably 10 or so other items....and my proof of his “failed” Presidency are his horrid poll numbers.

Agree completely about Tik Tok & Bytedance. Force the MFs to sell.