At least five interesting things: Anything but protests edition (#65)

Government efficiency; Solar power; Data suppression; American wealth; Trade and manufacturing

Everybody seems to be fixated on the anti-ICE protests, but I’ve just written about that twice in a row, and I need a break. So today’s roundup is a grab-bag of random unrelated stuff.

First, here are a couple of episodes of Econ 102, where Erik Torenberg and I talk a lot about ideas that are popular on the Tech Right:

Anyway, on to the roundup:

1. It turns out the U.S. government was pretty efficient after all

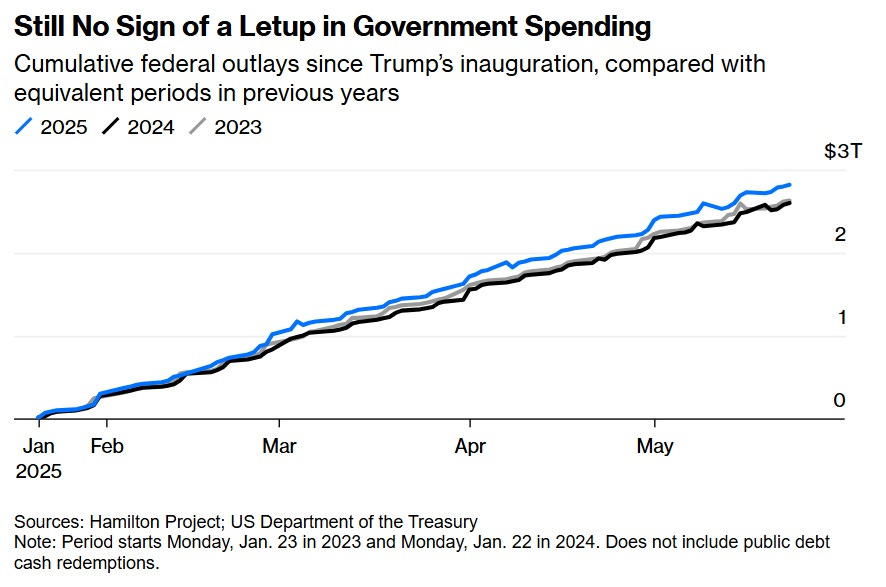

With Elon having left the government and publicly feuded with Trump, there’s now a general bipartisan consensus that DOGE was a big fat failure. The ad-hoc agency assisted somewhat with Trump’s general purge of progressivism in the government, but it failed to reduce government spending by any meaningful amount:

Its only major accomplishment, other than stationing a bunch of tech people in the civil service, was to gut USAID.

Trump is reported to have asked: “Was [DOGE] all bullshit?”. And yes, it was. Republicans have been claiming that we could balance the budget by getting rid of “waste and fraud” in the government since I was a kid. Then a Republican President gets elected, and those promises are forgotten, because it turns out there just isn’t much waste and fraud in the U.S. government.

This is apparently something that each new generation of American conservatives has to learn for themselves. DOGE is just another instance of this perennial learning process — this time, for the newly conservative “Tech Right”. NPR reports:

A former employee of the Department of Government Efficiency says that he found that the federal waste, fraud and abuse that his agency was supposed to uncover were "relatively nonexistent" during his short time embedded within the Department of Veterans Affairs…"I personally was pretty surprised, actually, at how efficient the government was," Sahil Lavingia told NPR's Juana Summers.

In fact, Lavingia said that he expected to find the same kind of inefficiency in the government that you’d find at a big company like Google, but discovered that government employees work harder than Googlers do:

I did not find the federal government to be rife with waste, fraud and abuse. I was expecting some more easy wins…And the reason is — I think we have a bias as people coming from the tech industry where we worked at companies, you know, such as Google, Facebook, these companies that have plenty of money, are funded by investors and have lots of people kind of sitting around doing nothing.

The government has been under sort of a magnifying glass for decades. And so I think, generally, I personally was pretty surprised, actually, at how efficient the government was. This isn't to say that it can't be made more efficient — elimination of paper, elimination of faxing — but these aren't necessarily fraud, waste and abuse. These are just rooms to modernize and improve the U.S. federal government into the 21st century.

Why is the U.S. government so hard-working, honest, and efficient? Probably because people have been worried about waste, fraud, and abuse for over a century, and so there have been repeated major efforts to make government more efficient. An example is Bill Clinton’s “reinventing government” initiative in the 1990s, which cut lots of federal jobs and reduced red tape and regulation.

By the time Elon & co. arrived on the scene, the low-hanging fruit of government efficiency had been picked.

2. Why solar is for real

Whenever you talk on social media about how amazing solar power is, skeptics always pop up to remind you that the sun doesn’t shine at night, or on cloudy days, or during winter, etc. Of course the easy response is that we can use batteries to store solar energy for when the sun isn’t out.

But that doesn’t fully answer the question. Because even if you have enough batteries to cover 90% of solar’s down time, what about the other 10%? It seems like you might need to build a parallel energy infrastructure — natural gas, nuclear, or whatever — just for that last little bit of time when the batteries are out.

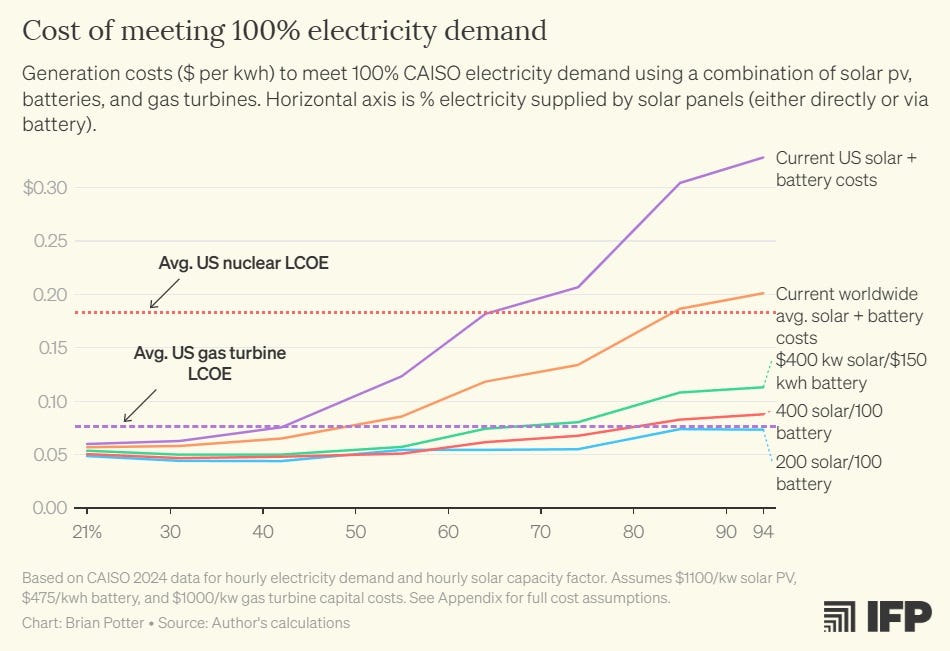

It’s a legitimate worry. But Brian Potter has an excellent blog post explaining why this isn’t actually such a big deal:

The basic point is that instead of building a giant natural gas plant capable of powering everything, you build a much smaller natural gas plant and have it charge some batteries too. Potter writes:

It is true that meeting 100% of electricity demand with large-scale solar PV requires some amount of parallel infrastructure, such as gas turbines, to fill in the gaps. But analysis suggests that at low enough solar PV and battery costs, this isn’t all that burdensome. Partly this is because in many cases (such as with gas turbines), a large fraction of electricity costs are due to fuel costs, which aren’t incurred when the system isn’t running. But it’s also because batteries can help reduce the need for this parallel infrastructure. Batteries aren’t just a complement to solar PV: they’re a complement to any energy generation system. We can use our gas turbines to charge the batteries too, helping us smooth out the peaks in demand and reducing how much “extra” infrastructure is required to meet demand. [emphasis mine]

He shows that even with modest cost reductions, solar power and batteries together could be capable of meeting 2/3 to 4/5 of our electricity demand more cheaply than if we were to use only natural gas:

Solar and batteries are still on their downward learning curves, so this amount of cost reduction is actually pretty likely (though for solar you have to take land use and installation costs into account, and those are falling more slowly than module prices).

In other words, the skeptics are wrong and solar is for real — at least if you consider 67-80% of our electricity mix “real”. I know I do.

3. Record grain harvests, comrade!

When Donald Trump started taking policy steps that looked likely to hurt the U.S. economy, a bunch of us worried that he would try to cover up bad economic data. This is a thing that dictators do a lot, and Trump often takes his cues from authoritarian leaders. In fact, the MAGA movement gets compared to Maoism rather frequently these days, and the Maoists were nothing if not skilled at ignoring the negative effects of their policies.

Furthermore, right-wingers have a tendency to accuse the U.S. government of manipulating its official statistics for (liberal) political purposes. These accusations are invariably false, but the fact that many right-wingers think the government does this may lead them to think “Well, if they’re doing it, we need to do it too.”

Derek Thompson sees signs that this fear is coming true:

Looking at these stories, I see some mild reasons for concern. Trump did indeed delay and alter a USDA report that said that Trump was going to increase deficits (which is true). But the report did come out, minus the section about the deficit. With regards to the CPI, Trump isn’t trying to block the data from being collected, but his personnel cuts at government statistical agencies have made it much harder to collect the data. And Trump did fire the people preparing a congressionally mandated climate assessment; it’s not clear whether he plans to hire other people to do it, or to simply ignore the mandate.

This is a far cry from the kind of epic self-deception that existed in the 20th century communist regimes — we’re not in “Record grain harvests, comrade!” territory. But it’s a worrying sign nonetheless. A nation that can’t get good information about how its economy is going will tend to make economic blunders and fail to correct them.

Interestingly, America is far from the worst country when it comes to suppressing economic data these days. China is much worse:

Not long ago, anyone could comb through a wide range of official data from China. Then it started to disappear…Land sales measures, foreign investment data and unemployment indicators have gone dark in recent years. Data on cremations and a business confidence index have been cut off. Even official soy sauce production reports are gone…In all, Chinese officials have stopped publishing hundreds of data points once used by researchers and investors…[T]he missing numbers have come as the world’s second biggest economy has stumbled under the weight of excessive debt, a crumbling real-estate market and other troubles—spurring heavy-handed efforts by authorities to control the narrative.

It’s not clear whether the country’s leaders still look at the data they’re suppressing, or whether they’d prefer not to hear the bad news. In any case, China is proving that communist parties are still second to none when it comes to information control.

4. Americans are getting richer, finally

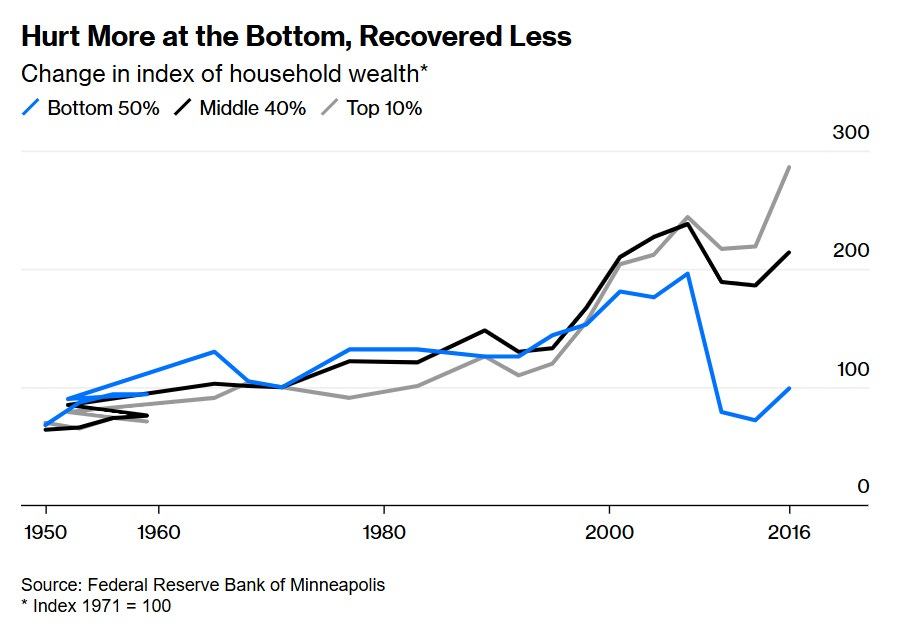

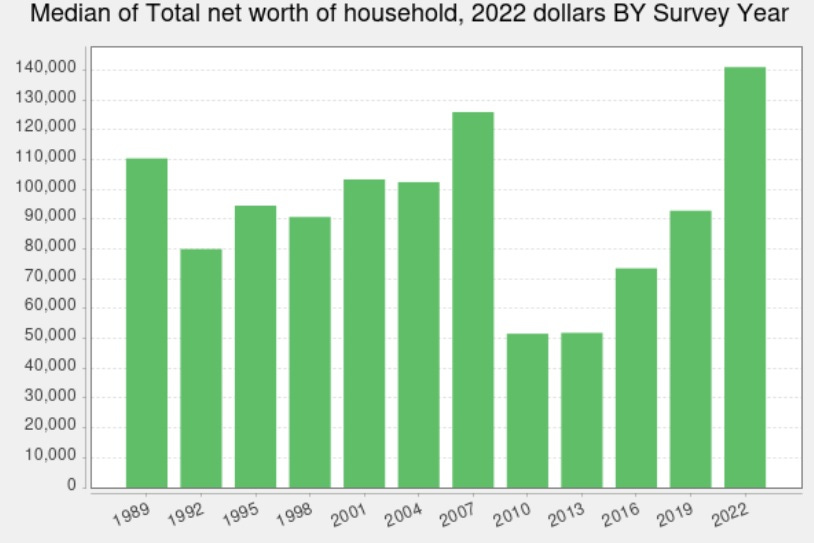

Economic pessimism has been ingrained into the American consciousness; these days we’re basically trained to think that there’s something deeply wrong with the way our economy functions. In 2018 I hypothesized that this conviction is a legacy of the financial crisis and housing crash of 2008, in which lots of Americans saw their wealth — which for middle-class Americans, is mostly contained in their houses — suddenly evaporate:

But that was almost a decade ago now, and things have improved a lot. House prices have gone back up, the middle class has paid off a lot of its debt, retirement accounts are way up, and the government transferred a bunch of income to regular folks during the pandemic. Put that all together, and middle-class American households had fully recovered from the housing crash by 2022:

If this trend continues, perhaps in another decade or so, Americans will regain some of the sunny economic optimism that they were known for when I was young.

5. How David Autor thinks we should revive U.S. manufacturing

Economists used to pretty much all believe in free trade. Then came the “China Shock” paper in 2016, by Autor, Dorn, and Hanson. This paper claimed that the massive surge of competition from cheap Chinese imports in the 2000s didn’t just create the proverbial “winners and losers”, but actually hurt America’s labor market overall. Other top researchers corroborated the finding. Suddenly, the free trade consensus was shattered, paving the way for the intellectual return of ideas like industrial policy, protectionism, strategic trade, and so on. If you ask protectionists what research supports them, they might not know any, but if they do, it’s probably Autor, Dorn, and Hanson (2016).

So it’s interesting to see what Autor himself — certainly the most vocal and well-known of the paper’s three authors — thinks about trade policy. Rogé Karma interviewed Autor for The Atlantic back in April; here are some excerpts from Autor’s answers:

I think the Trump folks are asking the right question [about trade]. But they’ve come up with just about the worst answer. It’s a classic case of fighting the last war. They’re looking over their shoulder, wishing we hadn’t made the mistakes we made 20 years ago. But what they are doing now is just compounding the errors.

The jobs that we lost to China 20 years ago: We’re not getting those back. China doesn’t even want those jobs anymore…They don’t want to be making commodity furniture and tube socks. They want to make semiconductors and electric vehicles and airplanes and robots and drones. They want those frontier sectors.

As it happens, those are the sectors we’ve actually held on to. But we could lose those too. We could lose Boeing. We could lose GM and Ford. We could lose Apple. We could lose the AI sector. These are the parts of manufacturing that generate good jobs but also so much more than that. They are where innovation occurs, where the big profits are, where technology and military leadership come from. And those are the sectors that we stand to lose next.

So the goal shouldn’t be to reverse the first China shock. It should be to prevent a China shock 2.0…

I actually think we can learn something from China’s example. Ten years ago, China decided they wanted to be at the frontier of a handful of sectors: drones, semiconductors, EVs, solar cells, etc. And for those sectors, they did a combination of protection alongside a lot of public investment…If we’re serious, we need to do something similar. The Inflation Reduction Act was one effort to basically jump-start the clean-energy and EV industries. The CHIPS and Science Act was trying to revitalize semiconductor manufacturing in the United States. We could do a lot more of that. We could turn the salvation of Boeing into a national project.

You also may need to protect these sectors with policies like tariffs. But that’s a targeted set of protections, sort of like the tariffs the Biden administration put on things like EVs and solar cells and semiconductors from China last year. And you need to combine that with huge government investments, commitments to public purchasing, investments in universities, bringing skilled talent from overseas, expanding the H-1B program. There’s lots and lots of things you can do…

Letting free trade rip is an easy policy. Putting up giant tariffs is an easy policy. Figuring out some middle path is hard. Deciding what sectors to invest in and protect is hard. Doing the work to build new industries is hard. But this is how great nations lead.

And right now, the United States is giving up on all of those things, even as China is doubling down on them. As a very patriotic person, I find that absolutely heartbreaking. We can do better.

I couldn’t agree more; this is almost all stuff I’ve been saying for the past five years, but said in a more concise way, and with the weight of Autor’s expertise and knowledge of the literature behind it.

Fortunately, I think more smart people are starting to coalesce around this basic policy package, even if the Trump administration is ignoring in favor of broad tariffs. An alliance of industrialist think tanks just released a document called “The Techno-Industrial Policy Playbook”, which takes a lot of the ideas Autor mentions and tries to operationalize them into real detailed policy prescriptions. I’m going to write a lot more about it soon, but you should definitely give it a read.

Your conclusion that the government must be efficient because the hasty DOGE exercise was a flop is hasty. Maybe DOGE was incompetent and unserious. Was it even trying to achieve efficiency, as opposed to just politicizing the government, which is likely to do the opposite?

A much more plausible hypothesis is that government has a lot of inefficiencies, but they come from democratically passed statutes and slow adoption of tech.

Everyone has experience of transacting with government vs. transacting with private companies, and the latter being far smoother. And the reason is pretty clear: of a private company is a pain to do business with, you walk away and go to its competitors, but you can't do that with the government. It's a monopoly. If you worry about monopoly, you should worry about government.

I agree it's naive to think there's lots of simple waste, fraud and abuse in government, and that a DOGE can find trillions of painless cuts. Rather, government people are locked by law into doing things in inefficient ways, and you don't have the pressure of the profit motive permanently shaping the culture in the direction of efficiency. That's why capitalism is better than socialism.

See Klein and Thompson's *Abundance* for a liberal friendly take on government underperformance.

The DOGE story misses one important point, the damage done to the science agencies. As an NSF funded scientist, I am concerned that the NSF has lost its Director and nearly all its senior admin, is in the process of reorganizing its science directorates, etc. As I understand it, NSF is currently being run by BigB@ll's 22 yo second cousin, and when it reopens with 1/3rd its former budget, it will only fund Crypto and Quantum Computing related projects.

Dark joking aside, firing the agency admins was always the point. Trump doesn't have the power to impound funds... the only way to drown the baby in the bathtub is just to fire ALL the senior admins and replace them with lackey's who will happily 'arrange deck chairs' with a puny budget (to mix metaphors).

I also know one senior scientist at a national lab who retired early after he got two Elon letters asking for bulleted lists. Now he regrets being retired.