At least five interesting things: Trump aftermath edition (#52)

Bad election narratives; principles for the Democrats; slowing AI progress; rising life expectancy; phones are bad; solar vs. nuclear

It’s been a long time since I did one of these roundups! The election sort of ate everything else, but now the interesting stuff is piling up again. I’ve decided to change the titles of these posts a little bit, to give each one a different name, in addition to a number.

Anyway, here’s the latest episode of Econ 102, in which Erik Torenberg and I talk about how to fix progressive cities:

On to the list!

1. Musa al-Gharbi debunks the standard progressive election narratives

Musa al-Gharbi has a great post exploring a bunch of the election data, and showing that the standard progressive stories about why Americans vote the way they do — racism, sexism, and so on — didn’t hold up in 2024:

Some excerpts:

[T]he GOP has been doing worse with white voters for every single cycle that Trump has been on the ballot, from 2016 through 2024…Meanwhile, Harris did quite well with whites in this cycle. She outperformed Hillary Clinton and Joe Biden with white voters. The only Democrat who put up comparable numbers with whites over the last couple decades was…Barack Obama in 2008…What’s more, the whites who shifted most towards the Democrats over the course of Trump’s tenure have been white men…

The problem Kamala faced was not with whites. Democrats had more than enough white votes to win the general election. Going all the way back to 1972, there have only been a few cycles where Democrats won a larger share of the white vote than they did in 2024…Democrats’ gains with whites in 2024 were more than offset by losses among non-whites — men and women alike…

This is not a new trend either: Democrats have been bleeding non-white voters in every midterm and general election since 2010…[I]n 2024, Democrats had their lowest performance with black voters in roughly a half-century…It’s been more than 50 years since Democrats performed as poorly with Hispanics as they did in 2024. There has been a lot of focus on Hispanic men in driving this outcome, but…Latinas shifted 17 percentage points towards the GOP…Democrats’ margin with Hispanic women has been halved over the last two elections…[T]he same shifts were evident among Asian American voters as well…

Democrats lost because everyone except for whites moved in the direction of Donald Trump this cycle. (emphasis mine)

Knowing that exit polls can sometimes be unreliable, al-Gharbi also notes that counties that are less than 50% White swung harder toward Trump than other counties. Basically, all evidence points toward substantial racial and gender depolarization in 2024. Al-Gharbi also shows that the electorate depolarized by age — young people moved toward Trump even as older people moved toward the Dems.

So all the standard narratives that progressives have used to explain the Trump phenomenon are just wrong. We are not seeing a dying old guard of White men clinging to a tottering ancien régime of patriarchy and White supremacy by voting for Trump. Instead, we’ve been seeing Trump push away older White men, while attracting the votes of Hispanic and Asian women, Hispanics and Asians in general, and young people.

If that isn’t a sign that identity politics isn’t working for the Democrats, I don’t know what would be.

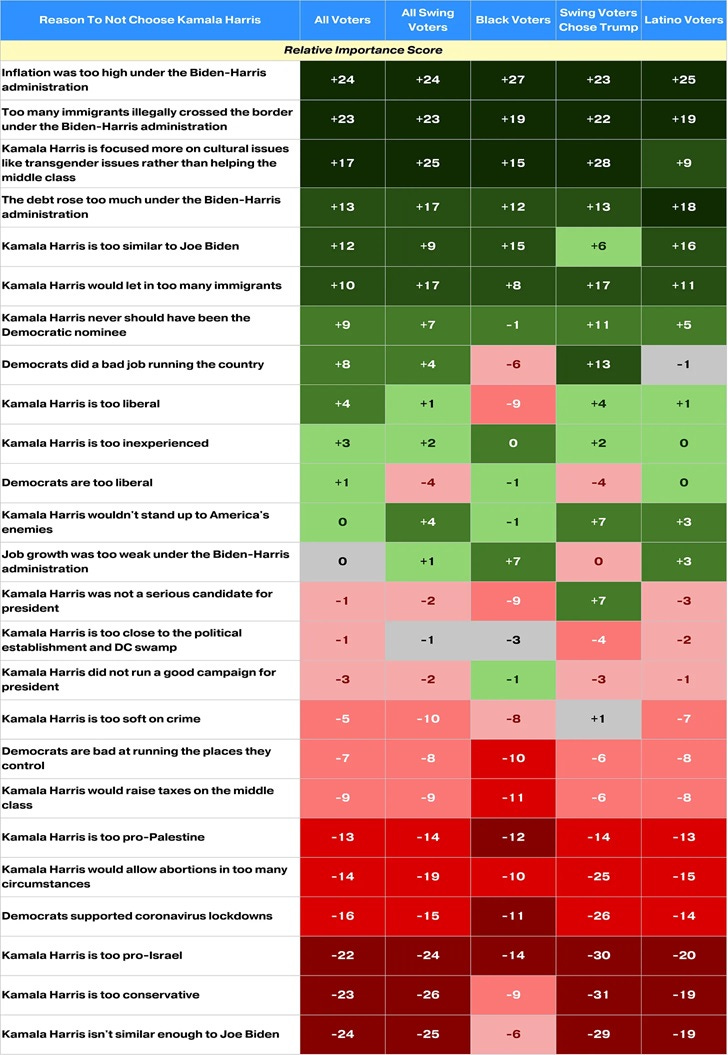

So what pissed off nonwhite voters, women, and young people so much? In general, polls show that Trump voters were mad about the exact three things everyone talks about them being mad about — immigration, inflation, and wokeness:

If Democrats want to win the country back, my advice is not to double down on the narratives of the 2010s. Don’t try to shame Latinos, Asians, and conservative Black people back into the fold by calling them “white-adjacent” or appealing to BIPOC solidarity or whatever. Don’t assume that women, minorities, and young people are natural Democratic constituencies. Don’t fool yourself into believing that demographic crosstabs represent cohesive “communities” that can be won over with identitarian appeals. Focus on crafting a message that works for all Americans.

Oh, and check out Musa al-Gharbi’s book.

2. Matt Yglesias’ principles for a Democratic comeback

Matt Yglesias is a much better politics writer than I am. And though we don’t always agree on stuff, I think his vision for where the Democratic party needs to go is definitely worth paying a lot of attention to:

Here’s his list of basic principles that he thinks Democrats should adopt:

Economic self-interest for the working class includes both robust economic growth and a robust social safety net.

The government should prioritize maintaining functional public systems and spaces over tolerating anti-social behavior.

Climate change — and pollution more broadly — is a reality to manage, not a hard limit to obey.

We should, in fact, judge people by the content of their character rather than by the color of their skin, rejecting discrimination and racial profiling without embracing views that elevate anyone’s identity groups over their individuality.

Race is a social construct, but biological sex is not. Policy must acknowledge that reality and uphold people’s basic freedom to live as they choose.

Academic and nonprofit work does not occupy a unique position of virtue relative to private business or any other jobs.

Politeness is a virtue, but obsessive language policing alienates most people and degrades the quality of thinking.

Public services and institutions like schools deserve adequate funding, and they must prioritize the interests of their users, not their workforce or abstract ideological projects.

All people have equal moral worth, but democratic self-government requires the American government to prioritize the interests of American citizens.

I think the one big thing Matt misses here (though his point #9 hints at it) is patriotism. Democrats should appeal to a shared, putatively universal American identity. A unified national identity supports the provision of public goods, because people feel that they’re “all in this together”. And using patriotic messaging makes it clear that the Democrats aren’t a sectarian party that wants to advance the interests of certain subgroups of Americans over others.

My one disagreement with Matt is on his point #3, about climate change. I think Matt has allowed himself to become too negatively polarized against the climate movement over the past few years. He’s justifiably annoyed by the fact that many (most?) Washington D.C. climate pressure groups are really just anti-capitalists using climate as an excuse for other crusades. Climate donors I talk to express this same frustration. And any whiff or hint of degrowth should be expunged from Democratic policy and from the progressive movement.

But green technology really works, and is in the process of transforming the world. Solar and batteries gotten so cheap that they now promise a future of cheap abundant energy that will accelerate rather than retard economic growth. The problems of intermittency and long-term storage are not a big deal. New research from economists at Brookings shows how saving the climate and accelerating growth are no longer at odds:

In this paper we assess the economic impacts of moving to a renewable-dominated grid in the US…Power prices fall anywhere between 20% and 80%, depending on local solar resources, leading to an aggregate real wage gain of 2-3%. Over the longer term, we show how moving to clean power represents a qualitative change in the aggregate growth process, alleviating the “resource drag” that has slowed recent productivity growth in the US.

Green tech is one of the keys to productivity acceleration in the decades ahead. Coincidentally, batteries also happen to be the thing that will power the weapons that dominate the battlefield in the years to come — drones and other EVs. So the objectives of economic growth, national security, and fighting climate change all converge. The faster we can accelerate the deployment of solar and batteries, the better.

Anyway, in general, Matt’s principles seem much much better than either of the two standard alternatives of 1) doubling down on identity politics and shaming minority voters for being “white-adjacent”, and 2) trying to replace identity politics with Bernie-style class politics that basically never win elections.

3. Some small signs that AI progress is slowing down

I think it’s safe to say that the biggest technological change over the past two years has been the advent of generative AI — especially LLMs like ChatGPT and Claude. A whole lot of people, especially in my own social scene, expect this progress to continue, or even to accelerate, in the years to come. Key to that prediction is the scaling hypothesis — the notion that if you just keep training A) bigger models on B) more data with C) a larger amount of compute, generative AI will get better and better at all the metrics that matter.

Here’s a good post about the scaling hypothesis by Dwarkesh Patel:

One of the most ardent believers in the scaling hypothesis is Dario Amodei, CEO of Anthropic, whom Erik Torenberg and I talked to a few months ago:

I occasionally hear AI people use the phrase “scale to AGI”, meaning that they think that if we just get enough model parameters, data, and compute, generative AI will become a godlike superintelligence capable of replacing human workers at essentially any task. AI engineers tend to believe that scaling to AGI will happen in the next few years. As an example, check out Leopold Aschenbrenner’s “Situational Awareness”.

The reason people believe in the scaling hypothesis, simply put, is that that’s what has worked so far. For decades, AI researchers tried a huge variety of approaches to create machines that seemed like they could think, with only incremental progress. Then in the early 2010s, engineers realized that if they just massively scaled up model size, data, and compute, they could achieve qualitatively better results. The rest is history. So why not just…keep doing that?

But in recent weeks, a number of people have started to claim that the benefits of scaling are slowing down. The Information reported that OpenAI’s new models show more incremental improvements than their previous ones. Reuters reported that Ilya Sutskever, one of the world’s leading LLM researchers, is pessimistic that scaling will be enough to sustain rapid progress:

Ilya Sutskever, co-founder of AI labs Safe Superintelligence (SSI) and OpenAI, told Reuters recently that results from scaling up pre-training - the phase of training an AI model that use s a vast amount of unlabeled data to understand language patterns and structures - have plateaued…“The 2010s were the age of scaling, now we're back in the age of wonder and discovery once again. Everyone is looking for the next thing,” Sutskever said. “Scaling the right thing matters more now than ever.”…Behind the scenes, researchers at major AI labs have been running into delays and disappointing outcomes in the race to release a large language model that outperforms OpenAI’s GPT-4 model, which is nearly two years old, according to three sources familiar with private matters.

One issue, as Reuters notes, is that the available data for training LLMs has basically run out. Researchers have known since at least 2022 that the amount of high-quality human writing in the world would only allow scaling to continue for a few more years, and copyright reduces the available amount even further.

But it’s also likely that the current crop of AI models has some problems that scaling just can’t solve. The main problem is “hallucinations” — i.e., lies. Everyone who uses LLMs is familiar with their habit of spouting falsehoods. Many AI engineers believed that scaling would eliminate hallucinations, but it doesn’t seem to be happening:

OpenAI has released a new benchmark, dubbed "SimpleQA," that's designed to measure the accuracy of the output of its own and competing artificial intelligence models…In doing so, the AI company has revealed just how bad its latest models are at providing correct answers. In its own tests, its cutting edge o1-preview model, which was released last month, scored an abysmal 42.7 percent success rate on the new benchmark…In other words, even the cream of the crop of recently announced large language models (LLMs) is far more likely to provide an outright incorrect answer than a right one…Competing models, like Anthropic's, scored even lower on OpenAI's SimpleQA benchmark, with its recently released Claude-3.5-sonnet model getting only 28.9 percent of questions right.

I’ve noticed this myself — while GPT-4 seemed to hallucinate less often than the original ChatGPT, later models like GPT-4o and o1 seemed to hallucinate more. It’s seeming more likely that hallucination is not a form of variance — a statistical error that can be eliminated with larger samples — but a form of asymptotic bias that will always plague LLMs no matter how big they get. LLMs seem unable to functionally distinguish truth from falsehood.

If that’s true, it means that the idea that we’ll soon “scale to AGI” is dubious. That doesn’t mean AI progress will hit a wall and we’ll get another AI winter — already, engineers are trying a bunch of new tricks. But it would mean that the road to “AGI”, whatever that is, could be longer and more uncertain than the people in my social circle believe.

Update: Here’s a post by Garrison Lovely on the same topic.

4. American life expectancy is rising again

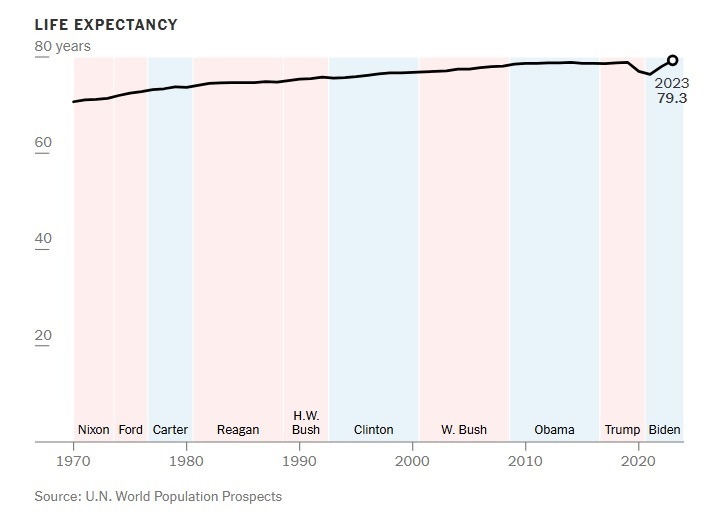

In the 2010s, U.S. life expectancy plateaued and even fell slightly. Then during the pandemic, life expectancy plunged, thanks to Covid (and, to a lesser extent, to increased murders, drug overdoses, etc.). This contributed to some very negative narratives about America and its future.

Yet even as those narratives have increased in volume, the trend itself has reversed. U.S. life expectancy is rising again, and has already made up the ground it lost in the pandemic:

In general, the country is looking a little healthier these days. Drug overdose deaths fell in 2023, murder has been falling since late 2021, and obesity is decreasing now as well.

As so often happens, rumors of America’s decline are greatly exaggerated.

5. Xi Jinping proves that phones are bad

I’ve been pretty negative about the effect of smartphones on human societies — a rare exception to my general techno-optimism. Anyway, I just saw a very interesting paper that strengthens my priors on the topic. Barwick et al. (2024) study the effects of Xi Jinping’s 2019 restriction of video game usage for minors. They find that the restriction improved both academic performance and labor market outcomes! The reason is that kids tend to play smartphone games rather than studying or going to lecture:

High app usage is detrimental to all outcomes we measure. A one s.d. increase in app usage reduces GPAs by 36.2% of a within-cohort-major s.d. and lowers wages by 2.3%. Roommates’ app usage exerts both direct effects (e.g., noise and disruptions) and indirect effects (via behavioral spillovers) on GPAs and wages, resulting in a total negative impact of over half the size of the own usage effect…Using high-frequency GPS data, we identify one underlying mechanism: high app usage crowds out time in study halls and increases late arrivals at and absences from lectures.

Score one for Xi Jinping’s social repression, I suppose. In fact, the U.S. can probably get most of this effect without tyranny, simply by restricting smartphone use in school — as some states are now doing. The question is how to limit smartphone usage for young adults without limiting their fundamental freedoms. Somewhat chillingly, the authors recommend that the Chinese government extend game time limits to college students. That isn’t going to fly in America, obviously. But we should find some way of discouraging young adults from being on their phones all day long.

Also, as an aside, this paper is evidence against the signaling theory of education. If education was mostly about proving your intelligence or conscientiousness or conformity or whatever, then making kids study less or skip lecture wouldn’t have much of an effect on their labor market outcomes. But it does.

6. Scott Alexander on solar versus nuclear

I met Scott Alexander in person for the first time at the Progress Conference a couple of weeks ago. He wrote up a long and very good summary of the conference:

I especially wanted to highlight his thoughts on solar versus nuclear energy, which is one of the biggest debates in the techno-optimist community:

Everyone [at the conference] agreed that we should have 100x as much energy per person (or 100x lower energy cost), that we should simultaneously lower emissions to zero, and that we could do it in a few decades. The only disagreement was how to get there, with clashes between advocates of solar and nuclear. This year, the pro-solar faction seemed to have the upper hand because of trends like [the falling cost of solar]…

Between 2010 and 2019, the nuclear/solar cost comparison fell from $96 / $378 to $155 vs. $68 (yes, nuclear got more expensive). As a result…solar’s share has dectupled in the past decade and shows no sign of slowing down…Why is solar improving so quickly? Humanity is very good at mass manufacturing things in factories. Once you convert a problem to “let’s manufacture billions of identical copies of this small object in a factory”, our natural talent at doing this kicks in, factories compete with each other on cost, and you get a Moore’s Law like growth curve. Sometime around the late 90s / early 00s, factories started manufacturing solar panels en masse, and it was off to the races.

Solar used to be limited by timing: however efficient it may be while the sun shines, it doesn’t help at night. Over the past few years, this limitation has disappeared: batteries are getting cheaper almost as quickly as solar itself…

The remaining limitation is high-density use cases; for example, a passenger jet…The solarists are undaunted: you can use solar power to “mine” carbon from the air and convert it into fossil fuels, then use the fossil fuels on the plane…

If these trends continue, solar power could reach $10/megawatt-hour in the next few years, and maybe even $1/megawatt hour a few years after that. This would make it 10-100x cheaper than coal, and end almost all of our energy-related problems. The United States could produce all its power by covering 2% of its land with solar panels - for comparison, we use 20% of our land for agriculture, so this would look like Nevada specializing in farming electricity somewhat less intensely than Iowa specializes in farming corn. Countries without Nevadas of their own could, with only slight annoyance, do the job with rooftop solar alone; one speaker calculated that even Singapore could cover 100% of its power needs if it put a panel on every roof. And developing countries could benefit at least as much as the First World; unlike other power sources, which require a competent government to run the power plant and manage the grid, ordinary families and small businesses can get their own solar panel + battery and have 24/7 power regardless of how corrupt the government is.

Despite this being a conference about the future, the pro-nuclear faction seemed comparatively stuck in the past. In the 1960s, nuclear was supposed to bring the amazing post-scarcity Jetsons future. It could have brought the amazing post-scarcity Jetsons future. But then regulators/environmentalists/the mob destroyed its potential and condemned us to fifty more years of fossil fuels. If society hadn’t kneecapped nuclear, we could have stopped millions of unnecessary coal-pollution-related deaths, avoided the whole global warming crisis, maybe even stayed on the high-progress track that would have made everyone twice as rich today. It was hard to avoid the feeling that the pro-nuclear faction wanted to re-enact the last battle, this time with a victory for the forces of Good…

I thought solar won: I’ve spent my whole life as an extending-lines-on-graphs fan, and it would be hypocritical to stop now.

I find it very hard to disagree with that analysis.

Solar power is fantastic and it is great that it is cheap. However the intermittency problem has not been solved. While it is conceivable that storage could be provided for hours and days using batteries, it will still be very expensive and require vast increases in mining, at least with current battery technology. It is possible, but not certain, that future battery technology will solve this problem.

A much more difficult problem is seasonal storage, which is needed in areas where there is very little sunshine in winter. Here there is no affordable solution yet. It is possible that hydrogen and synthetic fuel synthesis powered by solar will solve the problem, but we do not know that yet.

Given these uncertainties, it seems rash to abandon nuclear energy just because we think it may not be necessary. If the problems above are not solved or are very expensive to solve we are doomed to continue using fossil fuels or have much lower standards of living because of higher energy costs.

It relatively trivial, at least from an economic perspective, to make nuclear energy cheaper.

All that is needed is to make the regulations governing radioactivity more rational, using widely accepted data to guide this. I am qualified to write this a medical researcher who researches and teaches mechanisms of disease, including cancer.

There are four ways that the health risks of radioactivity are exaggerated.

(1) The first way is assuming the linear no-theshold (LNT) model is correct. The risks of radioactivity are currently calculated based on data that we have for harm at high doses extrapolated down to low doses. This assumes that risk decreases in a linear way with dose and that there is no threshold dose below which there is no harm. This linear no-threshold (LNT) assumption remains unproven but is probably impossible to disprove for the simple reason that the effects are so small at these low doses that they cannot be measured in any feasible real-world study. In my view there is no point in arguing about whether the LNT model is correct or not. I think, however, we can all agree that assuming the LNT model is correct is cautious.

(2) The second way that the risks of radioactivity are exaggerated is the assumption that the dose RATE does not matter. Current regulations assume that a dose received in 1 second (eg during exposure to an atomic bomb blast) is equivalent to a dose received in 1 year. We know for a fact that this is incorrect. This is why radiotherapy for cancer is given over many weeks (dose fractionation) rather than as a single dose.

The assumption that dose rate does not matter greatly exaggerates the risk of radioactivity released from nuclear reactor accidents and nuclear waste.

(3) The third way risks are exaggerated is in the ‘safe’ levels that is set by regulators. The widely accepted value for calculating the risk of radioactivity is that exposure to 1 Sievert (Sv) increases mortality by 5.5%. The safe level for public exposure to radioactivity is 0.001 Sv/year (1 mSv/year) above background. Assuming the LNT model is correct, this dose would increases mortality by (5.5/1000)% or 0.0055%. This is so low that it is impossible to detect, which is why the LNT model can never be disproved.

For comparison, the ‘safe’ level set by regulators for exposure to the most harmful form of air pollution, PM2.5 particles, is 5-15 ug/m^3. At this level PM2.5 air pollution increases mortality by 0.7%.

This is ~130 fold higher than the estimated mortality rate at the ‘safe’ level of radioactivity. In other words, our regulations value a life lost to radioactivity at least 100 times more than a life lost to air pollution.

This favours forms of energy that produce air pollution by burning stuff, such as fossil fuels and biofueld. Given that we are desperately trying to reduce fossil fuel use to avoid catastrophic climate change, this regulatory difference is unfortunate.

(4) The fourth way the risk of radioactivity are exaggerated is how regulators are required to treat breaches of the ‘safe’ limits. They treat breaches of radioactivity ‘safe’ levels far more seriously than breaches of air-pollution ‘safe’ levels.

One example is how regulators and public health officials respond when these levels are exceeded. When radioactivity from a nuclear reactor accident exceeds the safe levels, people are often forced to evacuate the area, often permanently. In contrast when PM2.5 air-pollution exceeds safe levels evacuation is not required. At most people are advised to stay indoors. One consequence of this disparity is that those forced to move from the Fukushima exclusion zone who were placed in cities like Tokyo were placed under greater overall risk of death because of higher air pollution.

A second example is how regulators require nuclear reactors to be built with numerous redundant safety mechanisms in an attempt to ensure that they never release radioactivity that breaches the ‘safe’ level, even after the worst possible (and thus unlikely) disaster. In contrast regulators do NOT require those building or operating machines (e.g. vehicles, fireplaces) or facilities (power plants, incinerators) that produce air pollution to ensure that humans are never exposed to air pollution levels that exceeds the ‘safe’ limits. Instead the ‘safe’ limits of air pollution are set as something to comply during normal operation of these machines or facilities. There is no expectation that they be designed such that the limits will not be breached even in very unlikely accidents.

This is discrepancy is particularly strange given that, as note above, the safe limit for radioactivity is at least 100 fold more cautious than the safe limit for air pollution. Regulators should, if they were rational, be far more relaxed about breaches of radioactivity limits than about breaches of air pollution limits.

Of these 4 forms of caution, the one most often debated is the LNT assumption. This is unfortunate as it is the only one that it is likely impossible to disprove. The other 3 are more easily shown to be too cautious.

What to do?

Since the safe limits for exposure to radioactivity are incredibly cautious/conservative (see 1-3), we should treat these limit the same way we treat safe limits for air pollution. They should be limits to aim for when a nuclear reactor is operating normally and when nuclear waste storage facility operates as designed under normal circumstances. Since exceeding these limits will not create significant risks, there is no obvious need to try to ensure nuclear reactors never have accidents or that nuclear waste never leaks. We do not do this for machines/facilities producing air pollution even though the safe limits are far less conservative.

Do we really need to decide in advance between nuclear and solar? With all of the different comparable energy jurisdictions around the world and even within North America it seems to me that we can watch and assess various real-time experiments with different mixes unfold and take our lessons accordingly. If solar + storage can out-compete nuclear, great. If not, also great (though solar-powered generation including wind is better when it comes to forestalling the waste heat problem that arises with 100x (!) energy use).