At least five interesting things for the middle of your week (#9)

Room temperature superconductors, Chinese economic gloom, geoengineering, consumer confidence, and YIMBY victories

I’m back from my week in Japan! Usually when I go, I write about Japan and talk to some people there, but this time I was showing friends around, so unfortunately didn’t have time to do that. So now I’m annoyed with all the fun stuff I didn’t get to write about while I was away, and I’m racing to catch up!

First, the fifth episode of my Econ 102 podcast with Eric Torenberg. In this one we talk about the future of higher education. Here’s Spotify:

And here are Apple, YouTube, and a subscription link for the podcast itself.

Anyway, on to the weekly roundup.

It was good to get excited about room temperature superconductors

The saga of LK99, a material that some researchers claimed was a room temperature and ambient pressure superconductor, appears to be drawing to a close. As physicist Michael Fuhrer explains, sagas like this one rarely end with a conclusive disproof of the initial claim; instead, they slowly peter out as replication attempts fail. Often, seemingly anomalous or strange results seem to pop up around the material or method in question, but they’re rarely the same strange results, and they don’t represent the kind of conclusive confirmation that a real breakthrough would quickly generate.

This seems to be exactly what’s happening with LK99. Replication attempts have all either failed or claim partial success or unexplained anomalies. Now a team of researchers from Peking University has published a preprint of a very careful replication attempt showing that LK99 isn’t a superconductor, just a ferromagnet. The apparent levitation of some pieces of the material was apparently just good old ferromagnetism. This paper appears to have convinced many of the online hypesters that LK99 isn’t a superconductor. (Update: Another paper finds no superconductivity, but does find a phase transition that can explain many of the anomalies other teams are finding in the material.)

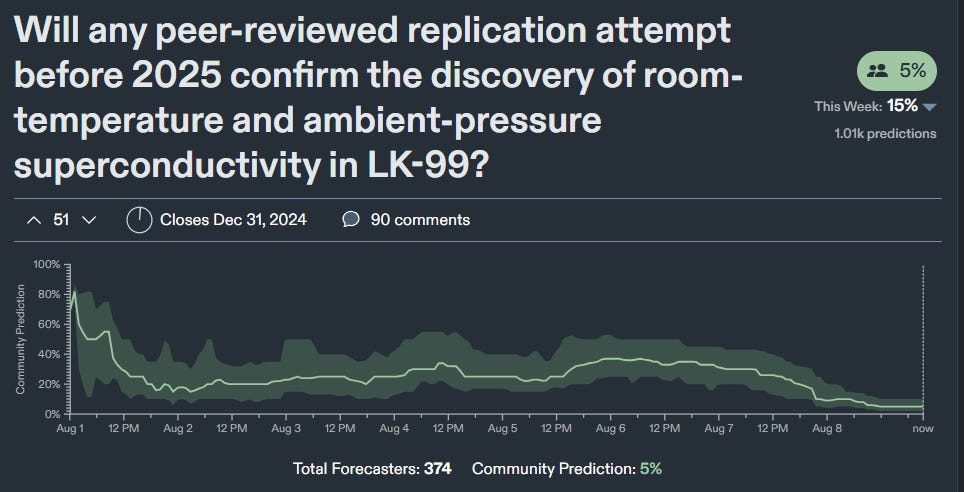

Meanwhile, general optimism about replication has collapsed:

A room-temperature ambient-pressure superconductor would be an amazingly useful thing, but we don’t appear to have one yet, and we don’t seem closer to getting one than we were a few weeks ago.

Which leads to the natural next question: Was this all just useless hype? Well, no, I don’t think so, for two reasons.

First, the episode introduced a lot of people to the scientific process firsthand. When two chemists claimed to have produced cold fusion in 1989, the public was simply a bystander to the process; when replication failed, most people either just read about that in the papers, or just forgot about the whole thing. But with the LK99 saga, people got to see firsthand how scientists approach claims of big breakthroughs. Social media gave them crucial background knowledge, quickly corrected myths and disinformation, and let people observe the replication attempts in real time. The fact that the candidate material was pretty easy for even hobbyists to make at home allowed some regular folks to participate in the replication attempt. That kind of broad scientific literacy seems like a good thing to me.

Second, the LK99 episode got people excited about rapid technological progress. Techno-optimism is one of the big themes of this blog, and it’s nice to see people amped up about a floating rock instead of about the latest culture-war food fight. And it’s not like there’s any shortage of real scientific breakthroughs out there to balance out the false alarms. Amazingly effective anti-obesity drugs seem to have been invented for the first time. MRNA vaccines are suddenly making big inroads against everything from cancer to malaria. Recent progress in generative AI and cheap space launch have been stunning. And even without world-transforming leaps, there are tons of significant advances being made in materials science all the time.

So hopefully LK99 will serve as a gateway drug to general techno-optimism.

China’s economy just keeps looking weaker

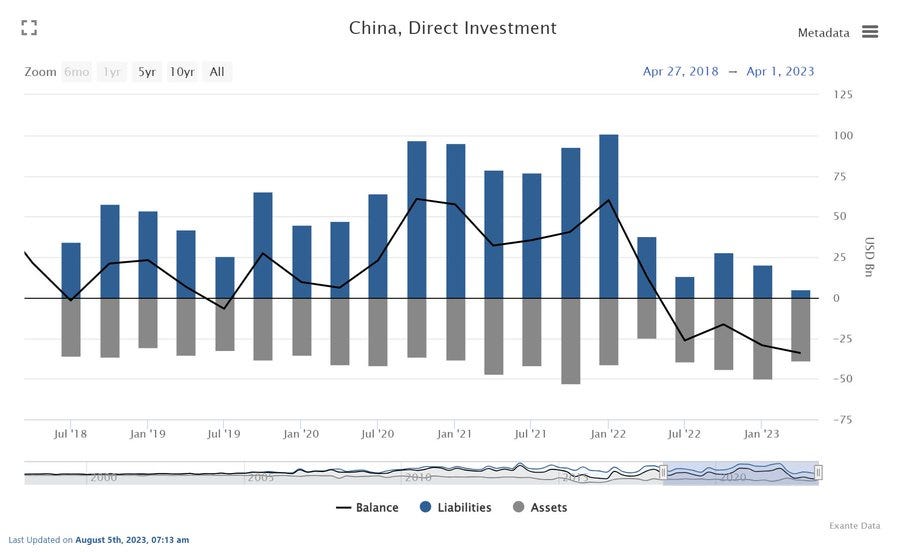

I’ve written about China’s economic slowdown a fair amount, but the negative news just keeps coming. Foreign investment in China is cratering at a rapid pace, as inflows collapse and outflows stay strong:

FDI is now back to 1990s levels in dollar terms — which will be much much less as a percentage of GDP.

There’s a good WSJ story about how local Chinese governments are going around begging foreign investors to invest, but few are biting. Some excerpts:

For Chinese leaders, keeping pressure on foreign firms while simultaneously trying to get them to invest is becoming an evermore precarious balancing act…

A trade official in Chengdu, the capital of southwestern Sichuan province, recently embarked on an investment-promotion trip to Europe. He returned empty-handed…A senior official in a county of southern Guangdong province…told a visiting American trade group recently that the county would reward any U.S. corporate “decision maker” investing there 10% of the value of the promised deal…The trade group turned down the county official’s offer, which in the U.S. would constitute an illegal bribe[.]

Why aren’t companies investing in China? In a word, risk. The biggest risk is the risk of war, but as the WSJ details, the country’s central government is already cracking down on foreign businesses in various ways, and the risk of companies getting their technology stolen has become more apparent. It’s important to remember that China’s successful industrial policy in the 1990s and the early 2000s was almost entirely local rather than national; it was a bunch of local governments going around and wooing foreign investors, and making sure their investments paid off. That’s not working anymore, because now the central government (i.e., Xi Jinping) has stepped in and started messing with the formula.

Plummeting FDI is far from the only piece of bad news for China. Exports are now falling, after a brief post-Zero-Covid bump:

Some countries, such as the U.S. and Japan, are diversifying their sources of imported goods. U.S. imports from China are down 24% just over the past year, despite the booming U.S. economy. Mexico has replaced China as America’s top trading partner. (Of course, in value-added terms this shift is smaller, since some of the stuff that other countries are exporting to America contains Chinese components inside.)

Meanwhile, China’s local governments are deeply in distress, with debts they can no longer pay. Most of these governments appear to be insolvent, since they don’t raise property taxes and can thus only pay back their debts with land sales, which doesn’t work very well during a real estate bust. They will probably have to be bailed out, but even then, their future ability to fund themselves.

How is Xi Jinping’s government responding to this flood of bad news? Exactly as you might expect an insecure dictator to respond:

Beijing is restricting local economists from discussing the country’s economic woes despite all signs pointing to rocky waters ahead.

Researchers at universities and think tanks and brokerage analysts told the Financial Times that they are being pressured to present economic news positively in order to increase public confidence. This coincides with earlier reporting from Reuters detailing how Chinese firms have been ordered not to discuss risks in offshore listing documents or face losing approval for IPOs.

Meanwhile, Chinese companies are being forced to consume ever more “Xi Jinping thought”, for up to hours a day.

Every day, my assessment of Xi’s general competence receives further support.

OK so maybe geoengineering works

You may have noticed that this summer is incredibly, unusually hot. I certainly noticed this on my recent trip to Japan, where temperatures reminded me of my childhood in Texas. Well, our intuition ain’t wrong, y’all; this is the hottest dang July in history.

One reason for this is El Nino, the ocean current phenomenon that exacerbates heat in certain years. But scientists have recently discovered another contributing factor: the end of an accidental geoengineering project. In 2020 the International Maritime Organization implemented new rules to cut the sulfur content of shipping fuel. Well, sulphur creates clouds, and these clouds were probably reflecting some sunlight away from the Earth:

By dramatically reducing the number of ship tracks, the planet has warmed up faster, several new studies have found. That trend is magnified in the Atlantic, where maritime traffic is particularly dense. In the shipping corridors, the increased light represents a 50% boost to the warming effect of human carbon emissions. It’s as if the world suddenly lost the cooling effect from a fairly large volcanic eruption each year, says Michael Diamond, an atmospheric scientist at Florida State University…

In Nature last year, [researchers] reported that these “invisible” ship tracks not only enhanced low lying marine clouds, as usual, but also markedly increased the volume of puffy cumulus clouds higher in the atmosphere, previously thought to be immune to the influence of ship pollution. They concluded that air pollution could be causing clouds to cool the climate at roughly double the previously projected strength.

Because its impact doesn’t rely on nearly as many modeling assumptions, the rule change is an unusually clean (get it?) test of the effectiveness of spraying sulfur into the air, which is one of the typically proposed methods of geoengineering. So now we basically know that spraying sulfur into the air does help keep the planet cooler, probably even more than we realized. But the effect does seem to be limited:

However, when the team then looked at the effect of the IMO rules on these invisible tracks, they received a shock: The decline in pollution didn’t make the cumulus clouds any less puffy, they report in a new preprint in Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics (ACP). It suggests these clouds have a saturation point, after which added pollution does little to increase their depth[.]

So I wouldn’t bet on geoengineering to solve our climate problems. Additionally, we want to be very wary of the law of unintended consequences; we only have one planet, and if we accidentally mess that up trying to fix global warming, that’s curtains for us. Spraying enough chemicals into the air to cool the whole world is likely to hurt it in other ways; sulfur in ship fuel was reduced precisely because it acidifies the oceans, destroying marine life. We must be VERY careful with geoengineering.

That said, we now know that least some modest amount of geoengineering is possible, so we should be looking for better ways to do it with minimal adverse environmental impact. And of course there’s carbon removal — the “other” kind of geoengineering — which seems like a pretty safe bet, since it just cancels out our emissions.

Are American consumers just mad about interest rates?

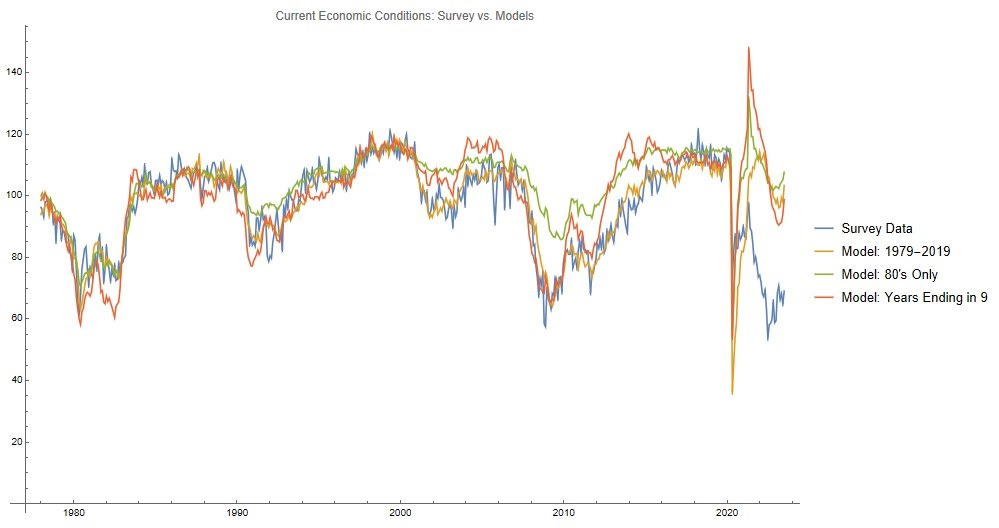

I’ve been writing a fair bit about consumer confidence, and why it’s in the tank even though the economy seems good along pretty much all of the standard measures. Over on the app formerly known as Twitter, a guy who goes by Quantian had an interesting thread trying to explain the anomaly. He picked 9 macroeconomic variables — inflation, unemployment, interest rates, stock prices, housing prices, real wages, and a couple others — and just ran a linear regression of consumer confidence on those variables. He found that this regression fit the pre-pandemic data very well, but didn’t fit the post-pandemic data at all:

Just to make sure the model wasn’t overfit, he did what’s called a pseudo-out-of-sample forecast, estimating the model on just the data from the 80s, and then projecting its predictions forward into later time periods. The linear model fits the data decently well until about summer 2021, at which point there’s a sharp break and the model just fails completely:

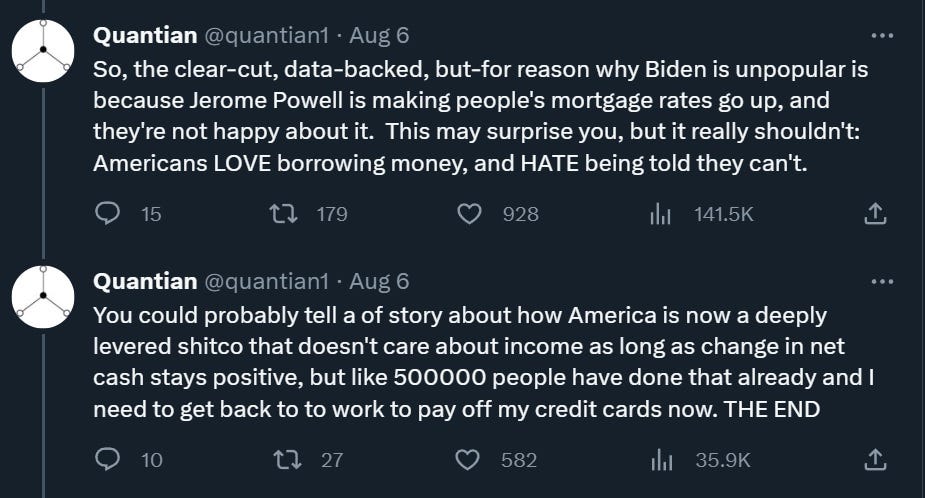

Quantian’s explanation is that the pandemic made Americans care a lot more about interest rates:

I am not sure I buy this explanation, for several reasons. First, the amount of time since the start of the pandemic is very short — we’re talking only about 30 data points here. Nor are these 30 data points a random sample; to name just one problem, the underlying time series has serial correlation, which makes inference much harder. Trying to explain 30 non-independent data points with a 10-parameter statistical model is basically hopeless.

So even if Quantian’s regression for the pre-2020 period does reveal something deep about the determinants of consumer sentiment, and even if there is a big trend break in 2020, Quantian’s post-2020 regression is highly unlikely to tell us much about what people care about since Covid. It could be interest rates. Or it could be the various political events since the start of 2020. Or something else. With such a short sample, correlations can’t really tell us that rates are the issue.

Another reason to be skeptical of Quantian’s explanation is the timing. You can see that around June of 2021, consumer sentiment starts to be weirdly lower than pre-2020 predictions would imply. But the Fed didn’t start hiking rates until 2022. So people started getting oddly pessimistic well before rates went up.

It’s also worth asking why Americans would care so much more about interest rates now than in the 90s, when mortgage rates were similar to today, or in the 80s, when they were much higher. It’s not because Americans are more burdened with old debt now — we’re not that deeply levered. Household debt to GDP is only a bit higher now than it was back then — 73%, compared to around 65% in the mid-90s and 50% in the early 80s. And because a lot of that debt is fixed-rate debt that was borrowed when rates were low, U.S. households’ debt service payments as a percent of disposable income are still near historic lows.

So not only is it not clear whether Americans suddenly care much more about mortgage rates in a post-pandemic world, it’s not clear why they would. It’s still a mystery.

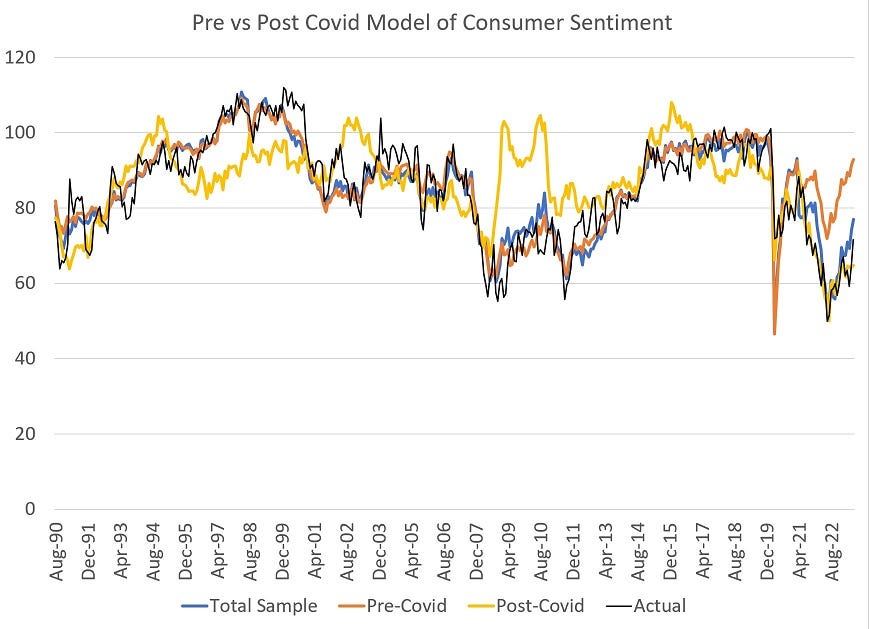

Also, a final statistical note: It’s not clear there really was a structural break in 2020. Michael Green ran a regression similar to Quantian’s, and when he estimated the model on the whole sample, he got a good fit for both pre- and post-pandemic:

YIMBYs are winning intellectually and politically

Another topic I’ve been tracking is the rise of the YIMBY movement, from an obscure local San Francisco idea to a nationwide push for housing abundance. Despite ferocious opposition from various forces on both the left and the right, the YIMBYs are winning the argument — and, increasingly, the political battle.

The most important piece of news here is that the Biden administration is now fully on board:

The Biden administration…announced further steps to lower housing costs and boost supply…The newly announced plan will leverage three separate areas toward achieving this goal: Easing land use and zoning rules, expanding financing and promoting the conversion of commercial to residential space…

To address restrictive land use and zoning policies – including those that prohibit multifamily housing development, among other issues, the administration is looking to incentivize municipalities to lift some of those restrictions by “incorporating land use and zoning into the grant criteria for the historic Reconnecting Communities and Neighborhoods program and also into the Economic Development Administration’s grant programs,” said [Biden economic adviser Daniel] Hornung.

Additionally, the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) is announcing a new program, the Pathways to Removing Obstacles to Housing program, which will provide communities with $85 million in funding to “identify and remove barriers to affordable housing production and preservation.”

This is important because one of the YIMBYs’ central arguments is that increased housing supply will push down rents and housing costs. There’s an intellectual countermovement on the left that argues that upzoning will drive up rents and exacerbate gentrification. The evidence was never on the side of that view, and the Biden administration seems to have decisively rejected it.

Meanwhile, YIMBY laws are beginning to result in significant new construction. Remember those state laws that legalized ADUs (aka “granny flats”) a few years ago? It turns out they helped increase housing construction. This is from the abstract of a new paper by Ishan Bhatt:

In 2016, the state of California legalized ADUs on most single-family lots in the state, overriding local regulations…I find upzoning had a significant effect on ADU construction. A single-family zone experienced .04 to .05 more ADUs permitted than a two- or three-family zone. Furthermore, I find that supply constraints strongly predict ADU construction, suggesting ADUs are filling gaps in rental supply.

And remember SB 35, the YIMBY bill that passed in California back in 2017 that streamlined various regulatory barriers to the approval of new housing projects? A new report from the Terner Center finds that over the past five years, the law facilitated about 18,000 new housing projects in the state.

Now, these are both pretty modest effects. ADU construction hasn’t yet been able to push rent down by more than a couple of percentage points, and 18,000 units is just two months’ worth of California’s overall permitting. But they’re not the most important YIMBY bills to pass — only the earliest. Recent years have seen a number of other, bigger successes, and there are probably even more to come, as the nation is forced to grapple with its housing shortage. It’s just nice to see that even the earliest, mildest YIMBY initiatives have created a bit of abundance.

Finally, there’s the tantalizing possibility that YIMBY attitudes are having an effect too. In an excellent thread, Nick Pinkston argues that America’s current high rate of apartment construction can’t be explained by high rents or by underlying costs, and therefore must be due to changes in policies and/or attitudes across the country.

That’s not definitive, but it sure does look hopeful. And regardless of the reason, it’s just great to see the apartment numbers go up.

In other words, despite all the noise on social media, the YIMBY idea continues to grow and win meaningful victories in the U.S.

These “X interesting things” posts are turning out to be as good and satisfying as Noah’s single-topic pieces.

I might be misunderstanding, but I’m struggling to understand how that quote from the abstract supports your point that deregulating ADUs “helped make housing more affordable.” The very next line of the abstract is “However, a linear panel model shows that ADUs are insufficient to decrease rent.”

Moreover, the author explicitly states later in the article: “I conclude that ADUs deregulation is not driving any meaningful reduction in rent prices.

This provides some evidence that reliance on single-family parcels is not an effective strategy to reduce rents.”

It seems like the evidence is showing deregulation increases supply specifically, but that hasn’t necessarily translated into statistically significant reductions in rental prices. Can you clarify this?