At least five interesting things for the middle of your week (#14)

Commercial real estate doom, education polarization vs. racial polarization, China's dodgy GDP numbers, phonics, and Russian nationalism

We begin, as always, with podcasts. This week we had a special extra episode of Econ 102, where Erik Torenberg and I interviewed our friend Adam Nash, CEO of Daffy, a company that helps people give away their money. Here’s the Spotify link:

And here are Apple Podcasts and YouTube. Erik wanted it to be a “debate”, but it turned out we didn’t really have much to disagree about.

Anyway, here’s our regular weekly Econ 102 episode, which is basically a recap of my recent post about why people in the tech world shouldn’t fall for Vivek Ramaswamy:

And here are Apple Podcasts and YouTube links.

Finally, Brad DeLong and I have another episode of Hexapodia!

In this one, we discuss various criticisms of the Left, by Brianna Wu, Matt Yglesias, and Ezra Klein. We argue about whether these criticisms represent a disagreement about the proper political means to achieve progressive political goals, or whether they represent deep fundamental disagreements about goals. I argue that some progressive activists are imagining societies that would simply be bad places to live — NIMBY pastoralist sprawls, degrowth, or urban anarchy — and that we should reject those goals as well as the political rhetoric those activists deploy in support of those goals. Not all progressives are right about what utopia looks like, and we shouldn’t pretend they are. Brad invents the excellent term “Schmittposting”, meaning the tendency of people to pick an enemy online and define their identity by shouting about that enemy.

Anyway, on to this week’s Five Interesting Things:

1. The threat from commercial real estate

Back in the late 2010s, a lot of econ writers tried to predict where the next recession would come from. The most common thing people were scared about was corporate debt, which grew a lot during the last decade. We argued a lot about whether corporations were levering up to a dangerous degree, or whether the higher debt was just a function of increased earnings. In any case, it appears we needn’t have worried; corporate debt to GDP is still a little higher than in the 2000s, but it’s been falling since the pandemic, and is now below the trend of the 2010s.

Now we’re in the middle of another expansion, and people are again asking what could cause a recession in the next year or two. The obvious answer is “higher interest rates”, but that still leaves the question of how higher rates will slow down the economy.

Standard macroeconomic models say that higher rates slow down the economy by making people consume less, because they decide to save more instead, to take advantage of the higher rates. That’s not a very realistic mechanism. But in any case, the American consumer does not look to be flagging:

There was also the fear that higher rates would cause bank failures by reducing the value of their Treasury bonds and other fixed-rate assets. Indeed, a few mid-sized regional banks failed earlier this year. But the financial system was largely fine, and there was no contagion to big or small banks.

Now, some people are talking about another possible threat to the economy: commercial real estate. Property developers borrow a lot of money to build offices and stores and such, and they have to periodically roll that debt over (i.e., re-borrow at whatever the current interest rate is). Higher rates make it a lot harder to borrow, which threatens to send a bunch of developers into bankruptcy.

On top of that, there’s the shift to remote work. Fully remote work has declined since the pandemic, but research by Nick Bloom and others suggests that some of the shift since the pandemic will be permanent. That’s going to increase the demand for residential real estate (because people will want more space for home offices), and decrease the demand for commercial real estate. A third potential factor is increased violent crime in downtown areas, but it remains to be seen whether that’s a long-term trend.

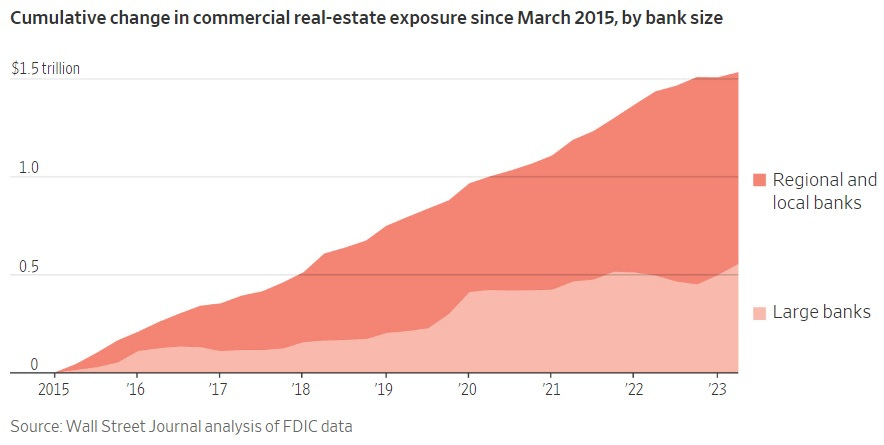

And if commercial real estate developers go bust en masse, banks are in trouble too. The Wall Street Journal has a lengthy article about how banks’s exposure to commercial real estate has increased in recent years. Here’s a key chart:

Now, I don’t like this chart a lot, because it doesn’t appear to be adjusted for inflation. Adjust for inflation, and it looks like banks’ exposure to commercial real estate will have flatlined in the last year or two. But still, much of the increased exposure happened in the years before the pandemic, when inflation was low. And this is just the increase since 2015; bank’s total direct and indirect exposure to the sector, according to the WSJ’s analysis, is about $3.6 trillion. That’s about 1/7 of total bank assets, I believe. So that’s a lot.

And on top of that, there’s the fact that businesses often use the value of their real estate as collateral to get cheap loans. If that collateral declines in value, it could make banks even less willing to lend.

A recession scenario is therefore not too hard to imagine. Commercial real estate eventually experiences a big bust when rates stay high for a couple years and it becomes clear that some workers are never going back to the office full-time. Banks then experience balance sheet weakness and companies have less collateral, both of which causes a pullback on risky lending, which then causes a general economic slowdown. The Fed cuts rates in response to the slowdown, which boosts the flagging commercial property sector, but not before the damage has been done.

It’s hard to know how likely this is, but it’s worth keeping an eye on.

2. Racial polarization is down, education polarization is up

Unfortunately, it’s politics season again in America. I used to get excited about election season; democracy is great, and elections gave us a chance to debate interesting policy ideas that lots of people would otherwise ignore. Ever since America’s age of unrest began in the mid-2010s, however, election season has become something worthy of dread — not only because of the rise of shouty social media, but because the main topics of American politics are identity cleavages and social conflict. If you’re a political scientist who says that it’s always been this way, and intones truisms like “all politics is identity politics”, well, you’re just wrong, and polls showing a dramatic shift in Americans’ priorities away from economic issues and toward “the government” and “poor leadership” and “the ability of Democrats/Republicans to work together” are just one piece of evidence showing that you’re wrong.

Unrest is a real thing, and it’s no fun.

A lot of pundits try to search for the source of unrest by looking at the demographic cleavages in American politics — party, race, religion, education, region, income, and so on. This approach carries an inherent risk — it’s all too easy to observe that 44% of Whites and 63% of Hispanics voted for Biden and say “Hispanics vote Dem and White vote GOP”, and then conclude that American politics are basically a race war. But if you can avoid this tendency, it’s useful to try to identify the axes of polarization.

Dan Balz of the Washington Post recently wrote a story entitled “What divides political parties? More than ever, it’s race and ethnicity.” This headline was probably an editorial mistake; Balz doesn’t actually claim that race matters more in politics than it used to, only that it still matters a lot. One of the huge downsides of writing for a major publication is that you don’t get to write your own headlines, and editors often make mistakes like this. But anyway, Matt Yglesias has a great post in which he rebuts the unfortunate WaPo headline. He posts this chart showing that racial polarization in presidential voting actually peaked in 2012:

What’s interesting is that this chart also suggests another source of division that actually does seem to be increasing in recent years: education polarization. The college/non-college breakdown in the chart is only for White voters, but it exists among other racial groups as well.

Political scientist William Marble has a new paper with data showing how the education gap has grown over time:

Race obviously still matters a lot; non-college Non-Whites still vote more Democratic than college Whites. But that gap was much much larger in the 80s and 90s than it is now. And a lot of the remaining gap is probably due to the extremely strong Democratic lean of Black voters.

In terms of what Democratic and Republican politicians should do in order to win elections, I’m not sure what the implications are here; maybe Dems should try to shore up their weakness among non-college voters, or maybe they should try to encourage college-educated voters to become even more Dem. I have no insight there.

But I think it is important for the commentariat — and regular Americans — to realize that higher education seems to be becoming an ever-larger determinant of the cleavages in American society. This is fundamentally a class divide for the age of knowledge industries — the human-capital bourgeoisie vs. the human-capital proletariat. Failing to recognize that class divide, and pretending to ourselves that our divisions are all about race, will blind us to some of the ruptures that have opened in our society.

3. Do you really think China is growing at 5%?

We in the commentariat spent a few weeks talking about how bad China’s economy is doing. This was important, because the “China is economically invincible” narrative that had taken hold in the previous few years needed to have a bit of cold water thrown on it, and the surge of pessimism created a useful opportunity to explain the downsides of China’s model. But the coordinated surge of China-pessimism will inevitably lead to a bit of a narrative whiplash when China’s growth doesn’t immediately go to zero. We can see this whiplash already happening, with reports that China did a bit better than expected in August. Expect a small burst of “China is back” stories, even as the real estate problems continue or worsen.

The narrative that China is still doing economically fine — which will be pushed by both China boosters and people whose job is to convince Westerners that China is safe to invest in — will be bolstered by China’s official growth rate. People from the IMF to JP Morgan and Bloomberg are still forecasting China to grow at around 5% this year — slower than before, and partially reflecting a bounceback from Zero Covid, but still far faster than developing countries. China’s government’s official growth target is now 5%, so when this target gets approximately hit, some commentators will take it as a sign that China has once again defied the odds and achieved a soft landing, that its growth deceleration is slow and controlled and probably a healthy thing anyway, and that the government is fundamentally in control and can hit its growth target it if wants.

And yet all of this will be based on an official number released by a Chinese government desperate to avoid the perception of economic weakness. So before you believe the narrative that China is growing at 5%, recall that there is a fairly large amount of evidence that China systematically manipulates its GDP numbers.

For example, Martinez (2018) looks at satellite photos of night lighting compared to GDP. He finds that in autocratic countries like China, there’s a much steeper relationship between night lights and GDP; for a given amount of lighting, autocracies report higher GDP numbers than democracies. His measure suggests that China’s GDP is about 12% lower than the official number — not a huge amount, but a sign that there is manipulation going on.

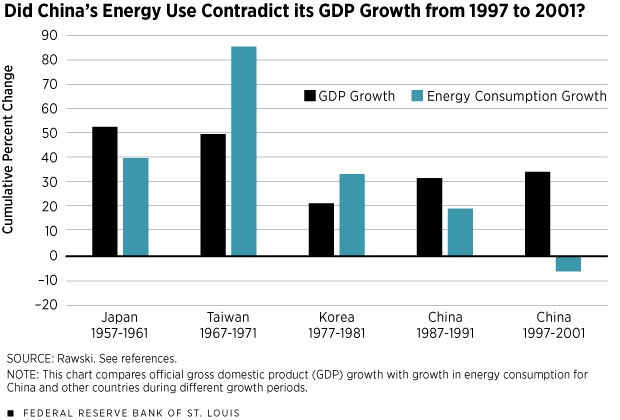

The real question is whether China steps up its manipulation in bad times, to avoid panic over recessions. For example, Rawlski (2001) found that after the Asian financial crisis of 1997, China’s energy use fell, while its official GDP continued to rise rapidly. This was fishy, not just compared with other countries in the region, but also compared with China’s own recent past:

The obvious hypothesis is that China overstated its growth temporarily in order to cover up a recession and make it look as if everything was going smoothly.

Nakamura, Steinsson, and Liu (2016) also find evidence of Chinese data smoothing, using relationships between household income and consumption to predict the true underlying rates of growth and inflation:

Our estimates suggest that official [Chinese] statistics present a smoothed version of reality…Our estimates imply that growth was substantially lower than official statistics suggest since 2002, and actually dipped into negative territory in 2007 and 2008.

Again, evidence points to data fudging being worst during a negative economic shock.

This makes perfect sense from a standpoint of political incentives. If you’re afraid that a recession will cause your regime to lose legitimacy, but you don’t want the public to completely lose faith in your economic numbers, you’ll cite generally correct or even slightly understated growth numbers in good times, and then basically fake the data to show that everything is fine during the couple of years when there’s actually a recession. Over the decades this causes you to slightly overstate GDP, but the discrepancy remains modest because recessions only last a year or two each time.

So I would not put very much confidence in that 5% number. Remember that this is a government that stopped publishing youth unemployment statistics when the number got too high, which has steadily reduced the number of official statistics it releases, and which has persecuted foreign consulting firms that tried to ferret out more accurate numbers.

4. We know a decent amount about how to teach kids effectively

When I was a kid, a conservative group called the Eagle Forum started campaigning in my hometown. Among their lists of demands, alongside things like teaching alternatives to evolution, there was a call to implement phonics-based education in reading classes. At the time, I thought that was kind of bizarre; why would some ideological pressure group care about the technical details of how kids learn to read?

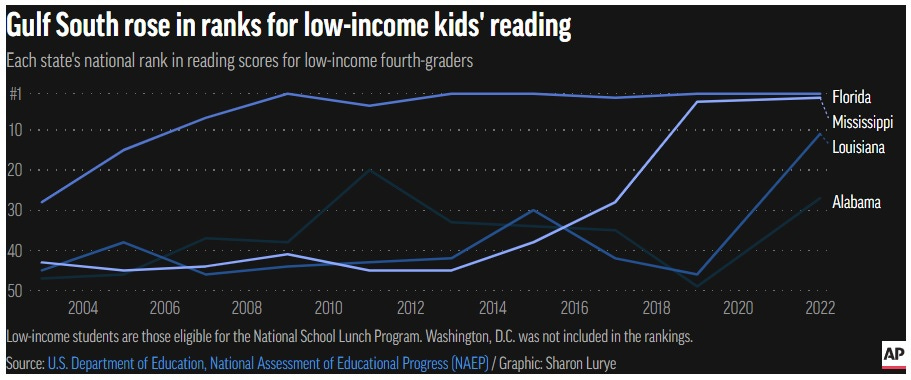

I never found out the answer, but then something even weirder happened — the Eagle Forum turned out to be completely right about phonics! (For those who don’t know, phonics just means sounding words out, instead of learning to read words in the context of whole sentences.) A bunch of states in the Deep South implemented a phonics-based approach along with some other reforms in the 2010s, and suddenly, poor kids in the Deep South started being able to read:

Now the general consensus among educators is that the evidence strongly supports phonics, and the approach is spreading all across the nation. Progressive organizations like the NAACP are fighting to get it implemented. Teachers are giving tearful testimonials of how powerful and effective the approach has been.

This episode, happily, seems like a win for both conservatives, who thought of an idea that worked, and for progressives, who followed the evidence. I still don’t know why phonics was seen as an ideological issue in my hometown in the 90s, but it seems to no longer be one.

It’s also a sign that we actually do know a few things about educational methods that work. Phonics is part of a larger series of approaches called “direct instruction” (or sometimes “systematic instruction”), which I know about because Alex Tabarrok likes to write about it. It’s basically just breaking lessons down into small achievable steps, and slowing lessons down or speeding them up according to the rate at which kids master the little steps. This is exactly the technique I always used in math tutoring, and anecdotally it gets great results, so it’s good to see the evidence confirming what I accidentally stumbled on.

Anyway, the success of the phonics revolution raises the possibility that we’ll implement phonics-like direct instruction methods for math too. The evidence seems to strongly support it. Hopefully the discovery of techniques that actually teach poor kids math will turn progressives away from the destructive approach of getting rid of math classes. It’s also likely that public schools will now be able to match the improvements shown by charter schools like KIPP.

And most importantly, what this shows is that education research isn’t useless. Yes, it’s hard to figure out what works. Yes, there’s a lot of politicized crap in there. But this isn’t a useless field; sometimes we make discoveries that lead to big meaningful improvements.

5. The Ukraine War will bring needed changes to Russian identity

I’m going to end this roundup with something a little different. Recently I’ve been reading some books about the breakup of Tsarist Russia. These include:

The End of Tsarist Russia, by Dominic Lieven

The Eastern Front, 1914-1917, by Norman Stone

Russia: Revolution and Civil War, 1917-1921, by Antony Beevor

These books are all worth reading (Beevor’s is the best-written and most engaging, as is typical of his books). But while they mostly focus on military details, ideologies, and the decisions of the primary actors of the period, they also present what feels to me like a coherent and consistent theory of Russian history.

Basically, Russia was and is a pretty standard European empire. It has a central “metropole” that’s ethnically homogeneous and highly nationalistic, and a bunch of subject peoples at the periphery. The metropole is the Russian heartland centered around Moscow, St. Petersburg, and European Russia in general, and “Russian” is the metropolitan ethnicity. The subject peoples traditionally included the Poles, the Ukrainians, the Kazakhs, and a vast array of other European, Central Asian, and Siberian peoples.

Traditionally, Russian ethnic nationalism, like British nationalism or French nationalism during their imperial periods, was focused on the idea that they were superior to the subject peoples at the periphery and had to teach them the true way of civilization. This is what Lieven calls “metropolitan nationalism”.

In reality, of course, the subject peoples received inferior treatment — they were the first to die when economic programs went wrong or harvests failed, as in the Holodomor, and they were used as cannon fodder in Russia’s wars. This practice has persisted all the way through the current Ukraine war, in which minorities have been sent to the front in disproportionate numbers and have taken disproportionate casualties.

The USSR, for all its weird ideological marketing, ultimately ended up as a continuation of the Russian imperial concept; minorities were starved, deported, and otherwise treated harshly, and peripheral regions were kept poorer than the Russian ethnic core. The end of communism in East Europe saw many of the subject peoples grow richer than Russia as they escaped its toxic embrace:

The fall of the USSR dramatically shrunk the set of peoples that the Russians could realistically view as their subjects. But it’s clear that Putin still thinks of Russia using the traditional imperial-nationalist concept:

With the stroke of a pen, Russian President Vladimir Putin on March 31 approved Russia’s latest foreign policy concept, its first since 2016…The nine-thousand-word concept starts by describing Russia as “a unique country-civilization and a vast Eurasian and Euro-Pacific power.” It adds that Russia “brings together the Russian people and other peoples belonging to the cultural and civilizational community of the Russian world.” In the Kremlin’s formulation, then, Russia is not so much a nation-state among nation-states as it is a civilizational world unto itself. This kind of language has been used by Putin for years and is increasingly prevalent among Russia’s elite. It is used to explain the reasons for the fall of the Soviet Union and chart a course for Russia’s redemption. This redemption is the creation of a new russkiy mir—here translated as “world” but also meaning “peace.”

To put it bluntly, this is not going to work. Russia only occupies about 18% of Ukraine, including Crimea; no matter how much territory Ukraine manages to retake, most of Ukraine will remain independent from Russian control and will join the EU economic sphere. This was really the Ukrainian war of independence, and when all is said and done it will have achieved its independence from its longtime imperial master. Meanwhile, other countries that Putin viewed as within Russia’s remaining sphere of influence, such as Kazakhstan and Armenia, are rapidly drifting away.

That leaves Belarus, the conquered bits of Ukraine, and Russia’s remaining minority regions like Chechnya as the last groups of people that ethnic Russians can realistically view as their imperial subjects. But population-wise, these are tiny; ethnic Russians now compose more than 75% of the population of Russia and Belarus combined. The Russians are running out of minorities to punch down on.

Ultimately, this will be a good thing for Russia. Because its empire was a contiguous land empire, it was able to hold onto it for far longer than Britain or France. But that only delayed the inevitable breakup. Now Russia will be the same thing Britain and France and the other European countries became after losing their empires — a nation-state with a supermajority ethnicity and a few domestic minorities. “Metropolitan nationalism” will be replaced by regular nationalism.

That will look scary and horrible in the short term; Russian nationalism will continue to be fascist and militaristic and repressive for a while. I wouldn’t want to be a minority in Russia during the next two decades. But ultimately, when Russian citizens realize en masse that their country is no longer an empire and they can no longer dream of lording it over distant subject peoples, they will begin to demand rights and economic opportunities and the other things that people in regular nation-states tend to demand. Majoritarian nationalism is often terrifying, but in the long term it’s a pretty stable and effective foundation for a nation-state. And when Russia becomes a normal country, it’ll have Ukraine to thank, for finally and forcefully destroying its imperial illusions.

“And when Russia becomes a normal country, it’ll have Ukraine to thank, for finally and forcefully destroying its imperial illusions.” I hope this occurs in my life time.

It feels a little bit rich to call the victory of phonics a victory for "progressives" as well as conservatives. Phonics is (plus or minus a rebranding) has been the normal way to teach literacy in alphabet-based languages for thousands of years. Progressives (I'll drop the scare quotes but please consider them to be still there) invented a whole new approach and managed to get it universally adopted without ever checking whether it worked, then conservatives fought against it, and after several decades of this the conservatives were proved right and the progressives eventually backed down when confronted with ovewhelming evidence.

I guess you could call it a victory for the Monte Carlo theory of social progress, in which progressives suggest a social change in a random direction, conservatives oppose it, the two groups fight it out for a while as we implement the change and figure out whether it's actually a good idea or not, and then one side backs down and we either keep the change or discard it. This way of running society actually works pretty well, but neither side seems to actually understand that this is the game they're playing -- they both seem to have a deep conviction that their side is always right, and a very short memory for all the times that their side has been wrong.